March 2020

No president ever leads alone. Moments of crisis tend to emphasize the people surrounding the president and offering support or guidance.

Cabinet officials should be the president's most important advisors. Ideally, they bring diverse perspectives, experiences, and expertise that inform decisions in moments of chaos. In fact, President George Washington created the cabinet to provide support when faced with constitutional dilemmas, domestic insurrections, and international crises. The cabinet precedents he established have largely guided his successors, and they determine whether a president is remembered by history as a success or failure.

We were saddened to hear that Presidential historian Richard Reeves, 83, passed away on March 25, 2020. Mr. Reeves was a frequent contributor to American Heritage (see the list of his essays).

A prolific columnist, Reeves was a harsh critic of both Republicans and Democrats, but willing to rescind past verdicts, such as his initial opposition to President Gerald R. Ford’s pardon of former president, Richard M. Nixon. Two decades later, he came to believe that Ford had made the right decision for the nation.

Editor's Note: Historian James Horn, a frequent contributor to American Heritage, is President of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent book, 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy (Basic Books).

Editor’s Note: Stephen Puleo is the author of seven books of history including the bestseller Dark Tide, The Boston Italians, American Treasures, and The Caning. His most recent, Voyage of Mercy, from which this essay is adapted, tells the dramatic story of the American efforts to save the Irish people suffering from famine.

The destruction of the potato crop had occurred — or, rather, revealed itself — almost overnight. The Reverend Theobald Mathew, a priest based in Cork city, Ireland, was one of the first to observe and report on the disaster. In late July, he was traveling from Cork to Dublin and saw fields of potato plants blooming “in all the luxuriance of an abundant harvest;” a sight that heartened him after widespread potato crop failure a year earlier had resulted in severe food shortages, but not full-scale famine.

America faced its greatest crisis in 1861 as the nation literally unraveled and the rest of the world wondered whether its experiment in self-determination would succeed.

Books about the period have generally focused on the efforts of Abraham Lincoln and the military to fight the Civil War. Much less recognized is that for four long and unpredictable years, Congress played a fundamental role in the waging and winning of the conflict, sustained the Union effort, and gave it lasting meaning. What happened in the political realm is an epic as gripping and fraught with uncertainty as what took place on the battlefield between the opposing armies.

It’s a human story of how men faced the worst crisis in the nation’s history. As Rep. Albert Riddle, a radical Republican, wrote: “Mr. Lincoln, his cabinet, and the 37th Congress were elected to do anything, everything, except what fell to them to do—fight the greatest civil war of history. It came upon them as an utter surprise.”

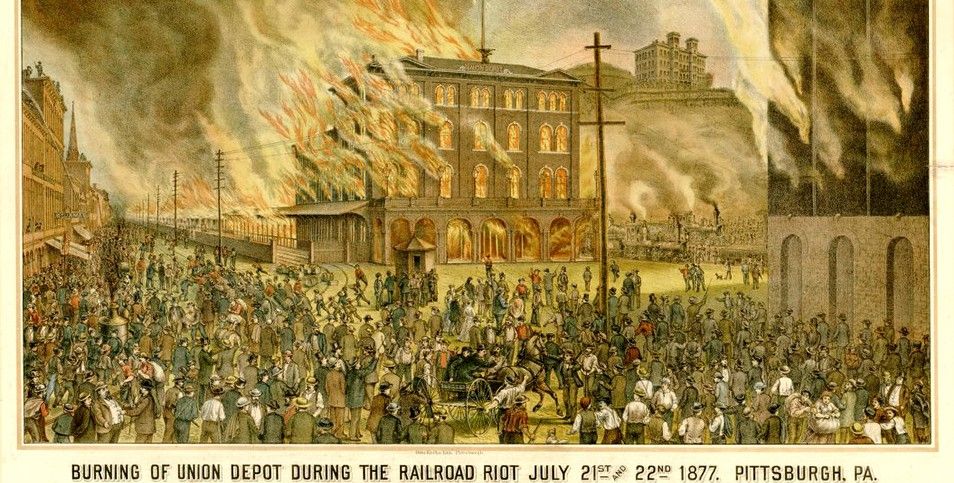

To the New York Tribune it was “an insurrection”; the St. Louis Republican called it “a labor revolution”; and the Pittsburgh Leader told its readers, “This may be the beginning of a great civil war in this country, between labor and capital.” The extraordinary events of July, 1877, did not quite add up to all that, but they certainly looked like a war while they were going on.

Editor's Note: John Barry is the author of The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, from which this essay is adapted.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln’s first day in office, a letter from Maj. Robert Anderson, commander of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, landed on the new president’s desk, informing him the garrison would run out of provisions in a month or six weeks.

Lincoln had to make his first, and one of his most important, decisions as commander in chief. Would he keep his inaugural vow to “hold, occupy and possess these, and all other property and places belonging to the government” at the risk of starting a war that might drive the rest of the slave states into the Confederacy? Or would he heed the advice of the Southern Unionists, Northern conservatives, and William Seward, his own secretary of state, and withdraw the troops to preserve the peace?

I’d scrutinized the economy every working day for decades and had visited the Fed scores of times. Nevertheless, when I was appointed chairman in August 1987, I knew I’d have a lot to learn. That was reinforced the minute I walked in the door. The first person to greet me was Dennis Buckley, a security agent who would stay with me throughout my tenure. He addressed me as “Mr. Chairman.”

Without thinking, I said, “Don’t be silly. Everybody calls me Alan.”

He gently explained that calling the chairman by his first name was just not the way things were done at the Fed.

So Alan became Mr. Chairman.

A half-century ago Chief Justice Earl Warren retired from the Supreme Court, marking the end of the Warren Court in 1969. In many ways, the Constitution as we know it today is the result of judgments handed down in the 16 years after President Eisenhower appointed Warren to be Chief Justice.

Despite its accomplishments, the Warren Court today does not have the reputation it deserves. Conservative critics attack it as “lawless.” Some supporters are defensive — suggesting, for example, that while the Warren Court did good things, its decisions were not always legally sound.