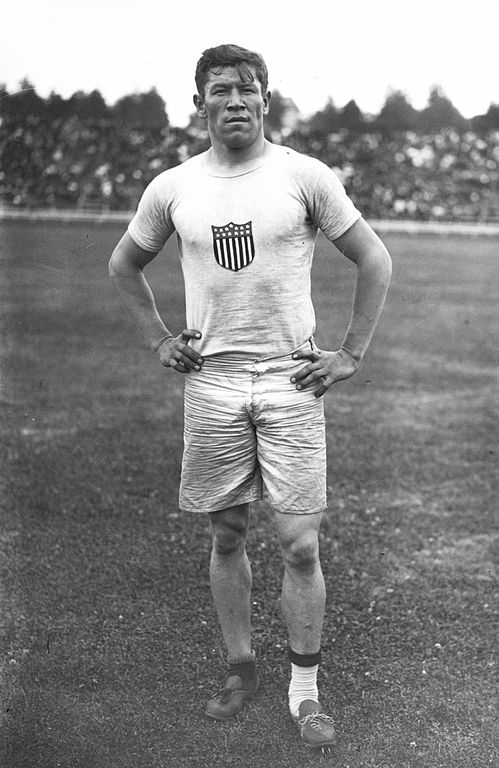

That’s what everyone agreed. Jim Thorpe was at the 1912 Olympics, but legend had to make him even more—and draconian rules had to take it all away

-

July/August 1992

Volume43Issue4

Americans have always demanded that their heroes be more than human. George Washington had to have thrown the dollar across the Potomac, Davy Crockett had to have wrestled a grizzly, Babe Ruth had to have come through for a dying boy with a promised home run. We all know that these stories are Sunday truths, but somehow the men wouldn’t be the same without them.

Likewise many of the stories about America’s greatest Olympic hero. Damon Runyon once remarked, “More lies have been told about Jim Thorpe than about any other athlete.” That may be true. Here are a few:

In the 1912 Olympics he won a gold medal in each event in which he competed—five, or eight, or ten events. He set records in each of those events, most of which stood for many years. He did this without having trained at all. In his twenty years of college and pro football, he never missed a tackle. He could run the length of a football field in ten seconds flat—in full pads. His average punting distance was eighty yards, and he could occasionally boot a hundred. On one long , touchdown run he tucked a would-be tackier under his free arm and carried him the last twenty yards.

What actually is true is that without much question Thorpe was the best all-around athlete in modern history. He is best known for winning the pentathlon and the decathlon at the 1912 Olympics and for his exploits on the football field. He was one of only a half dozen men who ever played both major-league baseball and NFL football; indeed, he was the first president of the National Football League. He also excelled at billiards, bowling, golf, swimming, gymnastics, rowing, hockey, figure skating, hunting, fishing, horseback riding, and dancing.

And he is the man whose Olympic medals were revoked on dubious grounds—possibly as a result of class prejudice. Because of that, his story became irresistible: that of the honest man struggling all his life for vindication, and finding it only posthumously. Today, eighty years after his triumph at Stockholm, the legend is complete. Jim Thorpe’s Olympic medals and records have been restored; Jim Thorpe’s name adorns the trophy that goes annually to the National Football League’s most valuable player; and Jim Thorpe is buried in a town named Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.

Thorpe was born—with a twin brother, Charlie—on May 28, 1888, near Prague, Oklahoma Territory (formerly Indian Territory), of an Indian and Irish father and an Indian and French mother. He was five-eighths Indian, descended from the Sac and Fox, Kickapoo, and Pottawatomi tribes, and was given the Indian name WaTho-Huck, meaning Bright Path. His father, Hiram Thorpe—a large, strong athlete who excelled at running, swimming, and wrestling—married several times and sometimes lived with two wives at once.

Thorpe’s parents were subsistence farmers who led a life that one biographer described as “English-speaking, but Indiantoned.” They and their neighbors farmed in Indian style and observed many traditional Indian customs, but they wore whites’ clothes and hunted with guns. Hiram Thorpe was an expert hunter. He also supplemented the family income by selling bootleg whiskey.

Jim Thorpe was close to both parents and inseparable from his twin brother. Charlie died of a fever at the age of eight, and after that Jim began to go through periods of craving solitude. Hiram had taught him to hunt, and Jim often went off alone with his gun and didn’t return home for days.

However, for the most part his boyhood seems to have been one long effort to stay in the race. Hiram was his frequent hunting partner, and the older man set a breakneck pace, sometimes covering thirty miles in a day. Jim’s favorite game with other Indian boys was follow-the-leader. He later wrote: “Our sports were not ordered or directed. They were just the spontaneous expressions of boys. They lay the physical foundation for future big performances.”

Thorpe got his first schooling at the Sac and Fox Agency School near home. He was a good student when he chose to be, but that was seldom. He gained a reputation as a class clown—which he lived up to the rest of his school days—and often ran away for short periods, mainly to go hunting.

He was attending Garden Grove, another Indian school that was near Prague, when he began to attract notice as a track and field standout. Glenn Scobey (“Pop”) Warner, who would become one of the greatest coaches in football history, was visiting Indian schools around the country to recruit athletes for the Carlisle Indian School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he was athletic director. He was eager to sign up Jim Thorpe.

Carlisle was the best known of the many Indian schools set up around the country in the last part of the nineteenth century to teach reservation children how to live like whites. Though only a high school, it admitted students as old as twenty-three, and its teams competed against the country’s top colleges. When Jim Thorpe set off for Carlisle, his father reportedly told him, “Son, I want you to show other races what an Indian can do.” Thorpe, like most Carlisle students, studied there briefly and then left to live with and work for a local white family for two years. When he had completed that stint of learning white ways in 1907, he was readmitted.

Some historians have portrayed Pop Warner as Thorpe’s mentor during his time at Carlisle, but that’s an exaggeration. If Jim Thorpe had a guiding light at all, it was his father. Hiram Thorpe died shortly after Jim left for Carlisle, and from then on Jim seemed to provide his own inspiration.

Warner later recalled, “I never had to do much coaching with Jim. Like all Indians, his powers of observation were remarkably keen. I guess Carlisle … provided me with the easiest coaching job I ever had.” If Warner had had his way, Thorpe would never have played football. Warner wanted him to devote his energies to track and field and feared he might injure himself on the gridiron. But Thorpe insisted.

He was not modest about his abilities. On his return to Carlisle, when he was nineteen, he made the track team by high-jumping 5′9″ in his street clothes. Warner informed him he had just broken the school record; Thorpe was unimpressed: “That’s not very high. I could do a lot better in a track suit.” And he did.

In 1908 Thorpe won the high jump at the prestigious Penn Relays. That fall he was named a third-team All-American running back. Then he took two years off from Carlisle. He had the chance to earn a little pocket money playing minor-league baseball in North Carolina, and he wanted to spend some time in Oklahoma hunting and fishing. Although he had no way of knowing it at the time, this innocent sojourn would be the biggest mistake of his life.

Pop Warner persuaded Thorpe to return to Carlisle for the 1911 football season with a promise to get him on the 1912 Olympic track team. Carlisle went 11-1 that year, routing such powerhouses as Penn, Brown, Pittsburgh, and Lafayette. Against Harvard, Thorpe gained 173 yards, more than half of Carlisle’s total offense, and scored all of Carlisle’s eighteen points—a touchdown and four field goals.

By now Thorpe had started to gain a national reputation. He was named a first-team All-American, and some experts started calling him one of the greatest halfbacks ever. The Pittsburgh Dispatch reported after one game: “This person Thorpe was a host in himself. Tall and sinewy, as quick as a flash and as powerful as a turbine engine, he appeared to be impervious to injury.”

In track the next spring he competed in five to seven events at every meet. In one he won the high jump, the shot put, and the 220-yard low hurdles, took second in the high hurdles and the long jump, and third in the 100yard dash. He was a hands-down qualifier at the Olympic trials for the decathlon, pentathlon, high jump, and long jump.

The American Olympic team trained as it sailed for Stockholm on the Red Star liner SS Finland. The swimmers worked out in a huge canvas tank, and the runners practiced on a deck covered with cork to muffle the sound of their footsteps. The great sportswriter Grantland Rice, among others, promoted the story that Thorpe didn’t train on board the Finland . And Johnny Hayes, who had won the gold medal for the United States in the marathon at the 1908 Olympics, claimed that Thorpe practiced for the long jump merely by drawing a chalk mark on the deck and staring at it from his hammock, before drifting off to sleep. But Thorpe’s teammates, including his future nemesis Avery Brundage, unanimously asserted that he trained as hard on the journey as any of them.

The 1912 Olympics represented a major step into modern times for organized sports. Electric timing equipment was used for the first time; so was a public-address system. The first of the four events Thorpe competed in, the pentathlon, took place on the second day, Sunday, July 7, 1912. He was expected to do well and finish perhaps as high as third. The smart money for the gold medal was on Ferdinand Bie of Norway, followed by Hugo Wieslander of Sweden.

Thorpe immediately upset the conventional wisdom by winning the pentathlon’s long jump, with a jump of 23′2.7″. In the next event he was at a disadvantage: it was the javelin, and he only recently had thrown one for the first time in his life. Still, his throw of 153′2.95″was good enough to take third place. In the 200-meter dash Thorpe took another first, running the race in 22.9 seconds; the favorite, Bie, finished a poor sixth. Then he hurled the discus 116′8.4″; Brundage took second, with a throw that landed more than two feet behind Thorpe’s.

The final event, the 1,500-meter run, was expected by many to be Thorpe’s downfall. He was well in the lead for the gold medal, but if he faltered and Bie won, the Norwegian would still have a chance. Bie started fast, and he and Thorpe were neck and neck at the three-quarter pole. But Bie finally faded and staggered in sixth; Thorpe kicked and won in a time of 4:44.8.

The scoring system for the pentathlon gave one point for first place in each event, two for second, and so on, with the lowest score winning; Thorpe finished with seven points: four firsts and a third. The silver medalist, Bie, was miles behind with twenty-four. The next day Thorpe competed in the high jump and the long jump (as separate events) and came in fifth and seventh respectively.

The decathlon, a ten-part event that incorporates every aspect of track and field, has always been considered the ultimate test of endurance and allround ablility; here the versatile Hugo Wieslander was Thorpe’s main competition. A heavy downpour greeted the athletes on the first day of the decathlon, July 13—a blow to Thorpe’s chances since he was known to be at his worst in foul weather. Sure enough, his American teammate E. L. R. Mercer nosed him out of first place in the 100-meter dash. Thorpe foot-faulted twice in the long jump because the jumping board was slippery, and his final jump of 22′2.3″ fell several inches short of first place. In the shot put, however, his throw of 42′5.45″ beat Wieslander by just over two inches. In decathlon scoring, times and distances, rather than the order of finish, are what count. Mercer, Wieslander, and the others couldn’t amass consistently high scores, and Thorpe ended the day well ahead in total points.

On the following day Thorpe came in first in the high jump, leaping 6′.6″. He finished second in the 400-meter, but in the 110-meter hurdles he was first again—this time with a recordsetting 15.6 seconds. By day’s end his lead in total points appeared to be insurmountable.

The third day was a walkover. Thorpe came in second in the discus, third in the pole vault, and third in the javelin. In the final event, the 1,500meter run, he finished first in an amazing 4:40.1—nearly five seconds better than his pentathlon time. His final point total was 8,412.955, a record that stood for twenty years.

Thorpe’s prize for each event was a gold medal and a laurel wreath, supplemented by a life-size bust of Sweden’s King Gustav V, presented by the king, and a silver chalice lined with gold and stones in the shape of a Viking ship, donated by Czar Nicholas II of Russia. Several pretty good stories came out of the presentation ceremonies. The most famous—and the only one generally accepted as true—is that when King Gustav presented Thorpe with his medals, he exclaimed, “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world!” and Thorpe, grinning shyly, replied, “Thanks, King.”

Other reports—gleefully malicious—had it that Thorpe snubbed the king, through sheer arrogance. Thorpe wrote in his private memoirs: “Someone started a story that when King Gustav sent for me, I replied that I couldn’t be bothered to meet a mere King. That story grew until it was related that the real reason I would not meet him was that I was too busy doing weightlifting stunts with steins of Swedish beer. The story was not true. I have pictures showing King Gustav crowning me with the laurel wreath and presenting me with the trophies and it is no fabrication that he said to me: ‘Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.’ That was the proudest moment of my life.”

No athlete had ever captured the public imagination so quickly or so completely. On his return home Thorpe received a ticker-tape parade in New York, a banquet in Philadelphia, a personal letter of praise from President Taft, and a triumphal procession back to Carlisle. That Thorpe was an Indian didn’t diminish his stature in the eyes of white fans, as being black certainly would have. In fact, his race was part of his appeal. The last Indian war was more than twenty years past, it was common knowledge that most Indians were having a miserable time on reservations, and there was some feeling of national guilt. Along with that guilt came a tendency to romanticize, to portray Indians as uniformly strong, brave, pure of heart, and indomitable “l of spirit. It was at about that time that sports teams began taking on nicknames like the Boston Braves and the Cleveland Indians. Thorpe would have been baffled by the notion that such names could seem demeaning.

That fall Thorpe was practically the whole Carlisle football team. The Indians tied one game and won the rest. In Carlisle’s climactic 27-6 walloping of Army, Thorpe averaged more than ten yards per carry. In the last game of the season, against Brown, Thorpe scored three touchdowns and kicked two field goals. Once again—as if there had been any doubt—he was named a first-team All-American.

Then, on January 23, 1913, came the blow that was to cripple his career and, finally, break his spirit. As often happens, an insignificant incident ended up rocking the world. A reporter for the Worcester, Massachusetts, Telegram , interviewing a minor-league baseball manager named Charley Clancy, happened to notice a photograph in Clancy’s office of a few of the players he had managed in the Carolina League in 1909. The next day the story broke that Jim Thorpe had been a professional athlete.

The rule that only amateurs could compete in the Olympics dated back to antiquity. In ancient Greece Olympians never competed for money until the Romans conquered Greece and introduced cash prizes. The games then turned into brutal, corrupt circuses and were finally banned in the fourth century.

When the modern Olympics began in 1896, strict rules about amateurism were imposed. “In Thorpe’s day the British aristocracy wrote the rules,” says Pete Cava, press information director for the Athletics Congress, which governs track and field nationwide. “The main theory is that their attitude was intended to prevent the working classes from competing, to keep the aristocracy from competing against undesirables.”

Bob Condron, associate director of public information and media for the United States Olympic Committee, points out that even “laborers were considered professionals. John Kelly, a rower who competed for the United States in the 1924 Olympics, was a bricklayer, and there was a movement to prevent him from participating because he had a job.”

Pop Warner and various people connected with the U.S. Olympic team had known about Thorpe’s baseball career but had simply hoped the story would never come up. And Thorpe himself had known the rules. Most of his fellows had played baseball under assumed names, to protect their amateur status; inexplicably Thorpe had taken no such precaution.

As soon as the word got out, the Amateur Athletic Union demanded an explanation. Thorpe did the best he could. In a letter to the AAU, he admitted the charges against him but added: “I was not wise in the ways of the world and did not realize this was wrong, and that it would make me a professional in track sports. … I never realized until now what a big mistake I made by keeping it a secret about my ball playing and I am sorry I did so. I hope I would be partly excused because of the fact that I was simply an Indian school boy and did not know all about such things. In fact, I did not know that I was doing wrong because I was doing what … other college men had done, except that they did not use their own names.

“I have always … only played or run races for the fun of the things … I have received offers amounting to thousands of dollars since my victories last summer, but… I did not care to make money from my athletic skill. … I hope the Amateur Athletic Union and the people will not be too hard in judging me.”

His hope came to nothing. The AAU demanded that he return his medals, and even his gifts from King Gustav and Czar Nicholas, to the International Olympic Committee (IOC). They were sent to Ferdinand Bie and Hugo Wieslander, and Thorpe’s records were expunged from the Olympic archives. Yet another anecdote claims that Bie and Wieslander sent the trophies back unopened, Wieslander commenting simply, “I did not win the decathlon.” Heartwarming, but not true. They both expressed regret at what had happened—and kept the booty.

Public opinion, on the other hand, was nearly unanimously in Thorpe’s favor, both here and in Europe. Newspaper columnists cited the countless college athletes who were subsidized by scholarships and accused the AAU and the 1OC of persecuting Thorpe because of his low social estate. The Buffalo Enquirer exclaimed that “the honest world … will always consider him the athlete par excellence of the past fifty years.” The Toronto Mail and Empire sneered, “The amateur world reels under the blow, and falls upon the rest of the world to stagger with it. The rest of the world, however, will decline to see any great difference between a man running a race and receiving $20 or $50 for his efforts, and a man running a race and receiving a gold watch.” But no amount of public outcry could sway the AAU, let alone the hidebound governors of the IOC. Campaigns were organized to have the sanctions reversed. Yet every effort met with stony resistance.

Thorpe pretended it didn’t hurt. He kept smiling and refused to criticize the IOC or the AAU. A few days after his medals had been returned, he and a female student won a ballroom-dancing contest at a school party.

His baseball career was the inspiration for several other tall tales. One of the best Thorpe told himself, about one of his first appearances with the Giants. “It was at an exhibition game in Texarkana, Texas …,” he claimed. “I hit three home runs in that game, one over the left-field fence, which was Arkansas; one over the right-field fence, which was Oklahoma; and one over the center-field fence, which was Texas.”

Two-thirds of the story is believable, but that second home run would have been especially impressive, since the Oklahoma border lies a good thirty miles from Texarkana. Why did Thorpe spin such an outrageous yarn? Probably he saw it as harmless fun. Perhaps he grew up telling tall tales as an ordinary part of Indian life. At any rate the story was one of the few bright spots of Jim’s baseball career or, indeed, of his whole life in the ensuing six or seven years. He married Iva Miller, the daughter of a Carlisle teacher, in 1913, and though the marriage was a happy one at first, they lost an infant son to polio in 1917. Thorpe, who had been drinking more heavily since the Olympian nightmare, now sank into an alcohol-sodden depression that caused irreparable damage to the marriage.

He reverted to his old pattern of disappearing for days or even weeks at a time. He was a good husband and father when he was around (he and Iva also had three daughters), but his wife didn’t know how to deal with his long absences and with his periods of despondency.

Thorpe bounced up and down between the major leagues and the minors from 1913 to 1919, always spending more time on the bench than in the field. He had an excellent throwing arm, which he used effectively from right field, but his fielding and batting statistics were mediocre.

The loss of his Olympic medals continued to gall him, at times nearly to obsession. Chief Meyers, the Giants’ catcher and a fellow Indian who was Thorpe’s roommate for part of his time in the big leagues, recalled many years later that “Jim was very proud of the great things he had done. A very proud man. … I remember, very late one night, Jim came in and woke me up. I remember it like it was only last night. He was crying and tears were rolling down his cheeks. ‘You know, Chief,’ he said, ‘the King of Sweden gave me those trophies, he gave them to me. But they took them away from me. They’re mine, Chief, I won them fair and square.’ It broke his heart and he never really recovered.”

Football was the game Thorpe loved best, and he seemed happiest when he was playing it. Rough by nature, he loved to hit and be hit. Although he continued to play minor-league baseball on and off until 1928, by the late teens he was much more involved with the brand-new concept of professional football.

In 1915 Thorpe signed on with the Canton, Ohio, Bulldogs for the thenfantastic figure of $250 a game. His first two games were against the Massillon, Ohio, Tigers, a team that starred Knute Rockne and Gus Dorais, who had revolutionized the game two years earlier at Notre Dame by introducing the forward pass, and who were playing under thinly disguised names in a crude but successful ploy to preserve their amateur status.

In the first game Thorpe was twice thrown for a loss by Rockne’s skillful tackling. The next time he had the ball, he smashed straight into Rockne, knocking him unconscious. When the Norwegian was hauled to his feet, Thorpe clapped him on the shoulder and remarked, “That’s better, Knute. These people want to see Big Jim run!”

And so they did. Thorpe played for the Bulldogs through 1920. He was as dominant then as he had been at Carlisle, a fearsome running back who could fake past tacklers or run right over them and who didn’t mind handing out a little extra physical punishment: his shoulder pads were illegally lined with sheet metal, and if you tried to tackle him, you would likely end up with a knee in your face.

On September 17, 1920, the American Professional Football Association (later renamed the National Football League) was formed in the showroom of Ralph Hay’s auto dealership in Canton. It consisted of seven teams from the Midwest, two of which, the Decatur Staleys and the Chicago Cardinals, were the Paleozoic versions of today’s Chicago Bears and Phoenix Cardinals. The organization’s chief purpose was to show that these were serious, bona fide professional teams, accredited by a governing body. The games still took place on a catch-ascatch-can basis until 1934, and players remained free to jump from team to team as the fancy struck them. Thorpe was elected president of the APFA, his only duty being to confer credibility on the organization by lending his name to its stationery.

In 1922 one of Thorpe’s hunting buddies, Walter Lingo, was looking for a way to publicize his Oorang Airedale Kennels, the world’s largest dog-breeding concern, and he and Thorpe hit on the idea of organizing an all-Indian pro football team sponsored by the kennels. They contacted several “old boys” from Carlisle and men who had played for other Indian schools around the country, and in no time they had a fairly respectable team.

The Oorang Indians made their debut in Marion, Ohio, that fall, with Thorpe as running back and head coach, two of his teammates from the Bulldogs, Joe Guyon and Pete Calac, and lesser-known players with picturesque names like Barrel, Hippo Broker, and Xavier Downwind. In a way they were the forerunners to basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters and baseball’s Indianapolis Clowns; the public paid to see their showmanship. Their games were preceded by exhibitions of Indian singing, dancing, and drumming by the players and stunts by Lingo’s Airedales.

The festivities were always well received; the actual games were less impressive. The Indians had a 4-7 record, including non-league games, in 1922 and dropped to 1-10 in 1923. The players, most of whom weren’t good enough for the NFL, started drifting away in the second season. Thorpe himself jumped to the Toledo Maroons. The Oorang Indians had served their purpose, which was to advertise Lingo’s Airedales. By 1924 the team was history.

And so were Thorpe’s best years as an athlete. His skills were fading with age. Still, he played for several other NFL teams until 1929, when he was forty-one. The story of his life after that is a bleak one. Fed up with his drinking bouts, Iva had divorced him in 1923. His football career over, he had to find a regular job just as the Depression began. He moved to Los Angeles, where he occasionally got small parts in movies, then drifted into construction labor. On one site he was spotted by a reporter and had to endure being the subject of a newspaper feature on the theme “How the mighty have fallen.”

Thorpe wanted to attend the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles but couldn’t afford a ticket. Vice President of the United States Charles Curtis, himself part Indian, invited him to sit in his private box at the Olympic stadium. When Thorpe appeared, the crowd of 105,000 gave him a standing ovation. In 1950 the Associated Press voted Thorpe “Athlete of the Half-Century.”

Those were rare bright spots. In the final third of his life, Thorpe drank heavily and was almost always strapped for cash. His second marriage, which lasted from 1925 to 1941, produced four ^ sons, but once again his wife grew unable to live with his moods and his absences. By the late 1930s he was earning a modest living giving lectures and making personal appearances. He got involved in some Indian political causes, but his principal avocation was his ongoing campaign to recover his Olympic medals. When his old Stockholm teammate Avery Brundage assumed the presidency of the IOC in 1952, some thought he would prove sympathetic. But Brundage was another gentleman of the old school, in both the good and the bad senses of the phrase.

Bob Condron, of the United States Olympic Committee, says: “Brundage was the foremost stickler for amateurism in the history of the Olympics. In later years the athletes called him Slavery Brundage.” So strongly was Brundage identified with the old antiprofessional snobbery that many people now believe it was he who stripped Thorpe of his Olympic medals in the first place, although he didn’t have a thing to do with it. He did, however, ignore the near-unanimous public opinion in Thorpe’s favor for decades, saying only, “Ignorance is no excuse.” Thorpe, for his part, may have nursed a great grudge against Brundage, but he was circumspect in public. He said, “I think Brundage is sincere in his beliefs.”

Jim Thorpe died of a heart attack in his trailer home in Lomita, California, in 1953. A movement soon got under way to erect a monument to him somewhere in Oklahoma, his native state, but political red tape prevented it. His body lay for months in a vault in Tulsa, waiting for a final resting place.

Late that year Thorpe’s widow (his third wife) saw a television documentary about a fund-raising project going on in the twin towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, which had fallen on hard times with the collapse of the local coal-mining industry. The editor of the Mauch Chunk Times-News , Joseph L. Boyle, was attempting to finance an industrial building to revitalize the area. “The day after the documentary was aired,” Boyle recalls, “Mrs. Thorpe contacted me and proposed that she’d move Jim’s body here if we’d erect a mausoleum and change our name to Jim Thorpe.”

At first the idea struck Boyle as preposterous—until he remembered that the two towns had been trying for years to consolidate their schools and government but had never been able to get past East Mauch Chunk’s refusal to take Mauch Chunk’s name. Boyle had the thought that a consolidation under the name Jim Thorpe could preserve local pride in both towns. “Mrs. Thorpe discussed the matter with town officials, and it was approved,” Boyle says. “We appropriated seventy-five acres of land for the memorial, most of which was used for a technical school. Thorpe’s body is near the school, under a marker that bears the words of King Gustav: ‘Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world!’ The name change has brought us things we’d never have imagined. We’re a reactivated tourist center; consolidation of our schools has led to great improvements in the curriculum; our local business has boomed. The name of Jim Thorpe is magical!”

Thorpe’s family and friends fought on after his death to have his Olympic honors restored. Brundage finally stepped down from the presidency of the IOC in 1972, and a major break-through came in the next year, when the U.S. Olympic Committee voted to restore Thorpe’s amateur status. “Rules on eligibility were changing drastically in the 1970s,” Condron explains. “The fact that some of the things Thorpe had done were not now violations probably had a lot to do with the reinstatement. Today you can play professionally in one sport and not be disqualified from competing as an amateur in another.”

Lord Killanin, who succeeded Brundage as president of the International Olympic Committee, was only slightly less inflexible than Brundage; his successor, Juan Antonio Samaranch, was far more sympathetic. “Samaranch just wants competition by the best athletes available in every sport,” Condron says. “He was adamantly in favor of opening up the Olympics to professionals.”

In 1982 the IOC voted to return Thorpe’s medals to his children and to put his 1912 records back on the books. Two years later, at the 1984 Winter Olympics, Canada fielded an all-professional hockey team. This summer the Barcelona Olympics will be graced by the likes of Magic Johnson, Martina Navratilova, and various others who for some years now have been making great sums at their chosen sports.

The majority of the public has no problem with professionals competing in the Olympics. As likely as not, a generation from now nobody will even think about the matter. But for some seventy years it was the most bitterly contested issue of the modern Olympics, and it started and ended with a man who honestly said he “did not care to make money from [his] athletic skill.”

Reputation was what Thorpe cared most about, and that he has. After most of a century he has got it back entire.