FOR MORE THAN A DECADE NOW, TENS OF THOUSANDS OF AMERICANS HAVE BEEN LEAVING LETTERS AND SNAPSHOTS, CIGARETTES AND CLOTHING AND BEER FOR THEIR FRIENDS, LOVERS, AND PARENTS WHO NEVER MADE IT BACK FROM VIETNAM

-

February/March 1995

Volume46Issue1

The faces of the "American Dead in Vietnam” was Life magazine’s cover story on June 27, 1969. Photographs and brief biographies of the 242 Americans killed in action during one week, from May 28 to June 3, marched on for pages. When the issue appeared, American troop strength in Vietnam was at an all-time high; President Richard M. Nixon had begun the secret bombing of Cambodia in March, and just days before press time he had announced plans to withdraw twenty-five thousand troops from Southeast Asia.

The article both tapped and fueled a surge in antiwar sentiment that culminated in that fall’s massive antiwar demonstrations. Exactly a quarter-century later a copy of that Life was left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. No explanation was attached. But in some way that yellowed issue spoke more than adequately for the continuing effect of the war on whoever left it.

The issue joined nearly forty thousand other offerings that have been left at the memorial since its dedication in 1982. Service medals, candles, combat boots, letters to dead lovers, dog tags, poems, unopened sardine cans, insignia, newspaper obituaries, prom pictures, wedding rings, birthday cards, Desert Storm memorabilia—it is a collection of writings and objects at once highly personal and yet so emblematic that it calls to mind the groupings of things that have been buried in time capsules.

Instead these items all go to MARS, a drab brick behemoth down the road from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in Glenn Dale, Maryland. MARS—for Museum and Archaeological Regional Storage—houses more than forty collections of objects from local parks and historic buildings in the National Park Service’s purview. Most of the twenty-five-thousand-square-foot warehouse, however, is taken up by the rows upon rows of steel cases, white acid-free Hollinger boxes, and rolling carts that hold the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection.

The collection is an anomaly worthy of the experience it reflects. Everything left at the memorial—which includes the black granite wall and two newer statues—has been picked up and preserved by the Park Service, save for live plant matter, which is thrown away, and unaltered flags, which go to civic groups. Splintering Popsicle sticks with illegible inscriptions are logged in alongside expert stained-glass likenesses of combat insignia. Yet the National Park Service has defined MARS as a storage facility and keeps it closed to the general public.

The sheer volume of new accessions has meant an unending backlog of uncatalogued items for the collection’s curator, Duery Felton, Jr., himself a seriously wounded Vietnam combat veteran, and his lone assistant. Since the Park Service formally began accumulating things from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1984, their numbers have steadily increased to an average of nearly a thousand a month.

That this flood tide of artifacts and documents shows no sign of ebbing even as the war itself recedes into the past testifies to the insistent role Vietnam continues to play in the national imagination. As that role has evolved, the memorial itself has become a combination of holy shrine and secular bulletin board.

Even before it was built, the designer Maya Ying Lin’s sunken granite chevron, conceived as a project for a Yale seminar in funerary architecture, inspired comparisons with a grave site. Its multitudinous detractors sometimes went much further: The veteran and author James Webb predicted the memorial would become “a wailing wall for future anti-draft and anti-nuclear demonstrators.”

It was initially so controversial that most political leaders, including President Ronald Reagan, refused to attend its dedication, in November 1982. But the emotional outpouring that accompanied that event was unprecedented for a public ribbon cutting; Washington absorbed the greatest influx of veterans since a Grand Army of the Republic encampment ninety years earlier. When the last speech ended, a hundred and fifty thousand people surged over the crowd-control fences and into the memorial’s embrace, weeping, searching, reaching, stroking the names engraved on its black granite arms. Thousands stayed on through the night.

Dozens of unusual mementos were left that weekend. Jan Scruggs, who first propounded the idea for the memorial, particularly recalls “a very haunting pair of cowboy boots. No note, no nothing. You could read your own story into it.” A couple of days later Tony Migliaccio, a National Park Service grounds supervisor, found a teddy bear, the earliest of at least forty stuffed bears left at the wall. It later became known simply as “the first bear.” No policy existed for dealing with boots, bears, letters, and other such things, so Migliaccio mentally labeled them lost and found, put them in a cardboard box beside the lawn mowers and lime sacks in his storage area, and figured the phenomenon would pass. It didn’t.

Most of the early offerings came from veterans or their close relatives. More often than not they were notes, letters, and cards that spoke directly to one of the 58,191 men and women named on the wall.

On notepaper from a Washington hotel:

"My dearest Paul

I finally got here—a beautiful monument for you.

I miss you—and I know you’re watching over me.

I love you. Your wife"

From a mother’s letter on Memorial Day 1983: “I see your name on a black wall. A name I gave you as I held you so close after you were born, never dreaming of the too few years I was to have with you.”

From the beginning the memorial has been a place where the living commune with the dead. Maya Lin herself described her creation as “an interface between the sunny world and the quiet, dark world beyond, that we can’t enter.” The granite’s mirrorlike polish, a crucial detail in her design specifications, adds to the effect; it lets visitors see their own reflections hovering over the names of their dead and merging with them.

Lydia Flsh, Director of the Vietnam Veterans Oral History and Folklore Project, calls the wall the “strangest of all sacred places,” describing it as a liminal site, or sensory or psychological threshold. A professor of folklore at the State University College at Buffalo, she has conducted fieldwork at many shrines and points out that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is one of them, a place of pilgrimage, of moral quests.

By the time the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund passed control of the memorial to the National Park Service, in 1984, the pilgrimage was well established. Hawaiian veterans arrived bearine a chain of orchids that stretched the entire length of the wall. Native American veterans have held tribal rituals there, bringing beaded eagle feathers, ceremonial war shields, and medicine bundles.

For the majority of Vietnam veterans who go to the memorial alone, however, the journey has offered a release from a sense of isolation. Some have left notes that speak of their arrival as a homecoming. Others have sought the expiation of guilt, another traditional impetus to pilgrimage. What has come to be called survivor guilt underpins thousands of apologies left for dead comrades.

“We did what we could but it was not enough because I found you here,” reads one. “You are not just a name on this wall. You are alive. You are blood on my hands. You are screams in my ears. You are eyes in my soul.

“I told you you’d be all right, but I lied, and please forgive me.”

As the memorial became a place for pilgrimage, its creator’s intentions were, on various levels, borne out. “I didn’t want a static object that people would just look at,” Lin has written, “but something they could relate to as on a journey, or passage, that would bring each to his own conclusions.” The descent toward the wall’s vertex, where the names tower overhead, symbolized that journey. The arrangement of those names is even more suggestive.

During the wall’s construction, some veterans demanded that the dead be listed alphabetically; hundreds of Smiths and Joneses, and some identical names, would have appeared telephone-directory-style, one after another. Lin stuck to her demand that the names be listed in chronological order of death and alphabetized within each day. As the war progressed, every day held its own story. The wall would repeat those stories. Here were the nurses who died with their patients when a field hospital came under attack; there, a son’s name among those of buddies he had mentioned in letters home.

Each day’s casualties would be threads in the narrative of an epic poem. But by its very design the memorial presented a broken narrative: The 58,196 names begin at the vertex on the east wall, under the date 1959, continue panel by panel eastward, in the direction of the Washington Monument, and then stop before the sequence resumes at the far end of the west wall and moves east toward the vertex and the last panel, above the date 1975. That broken circle, Lin envisioned, would be completed by each visitor.

The arrangement seemed fitting for war that had had no conventional narrative structure—a war without a clear beginning or end, without well-articulated goals, fought sometimes with scant regard for geographic boundaries and, indeed, remaining undeclared, technically not a war at all. Circumstances had conspired to isolate the GI from nearly everything beyond a concern for his own survival during the usual 365-day tour. Soldiers in Vietnam rarely fought in the units they had trained with, nor, when it was over, did they come home with comrades. The World War II troopship with its slow, gradual communal return to a world beyond war gave way to a swift, solitary plane ride to a country filled with people who knew little of the GI’s sacrifice.

Suddenness also marked the removal, by strangers, of dead or wounded comrades from the battlefield. Medevac usually came so quickly that many GIs never knew until they searched the wall whether a friend had lived or died. “How angry I was to find you here,” wrote one vet to his dead comrades.

Maya Lin’s wall offered the veterans a place not only to mourn but also to add bits of their own fragmented experience to the collective narrative. This is what happened , many of the messages seem to say. A fourpage letter addressed to the soldiers of the 101st Airborne begins: “The worst memory for me is the day I sent the 76 men out of your 85 to their deaths. I have to explain and I pray to God you will understand.” And the plain truth needn’t be verbal: The shell that had killed a comrade was both an obituary and a tribute.

Particular kinds of offerings that tend to show up repeatedly say specific things about how GIs experienced the war. Food and drink —whiskey, canned ravioli, peanuts—often appear at the wall. The donors are usually veterans, who remember vividly the lack of these things. Tins of sardines and bottles of beer, transformed into votives, replace those borrowed or purloined years ago in Asia. Army-issue can openers show up by the dozens. Bags of M&Ms appear without explanation; Felton believes they pay tribute to the underequipped medics who administered them as placebos when the morphine ran out.

Along with their dog tags come parts of GIs’ uniforms: headgear, k fatigues, dozens of pairs of combat boots, flak jackets, patches. The sheer variety suggests the vast web of service units that operated in Vietnam, as well as the war’s long duration. Boots, for instance, progress from old-style Army footwear, brittle from storage since Korea, to Panama-soled ones that resisted booby traps and punji sticks.

Families and friends offer civilian mementos of the men and women they knew: a golfer’s clubs, a musician’s trumpet, a hobbyist’s model car. A canvas bag recalls a paper route. “Floyd, you get one free throw,” wrote “Lil’ Sis” on an All Star basketball. High school varsity letters and pennants echo the fact that the average age of the American soldier in Vietnam was nineteen—seven years younger than his World War II counterpart.

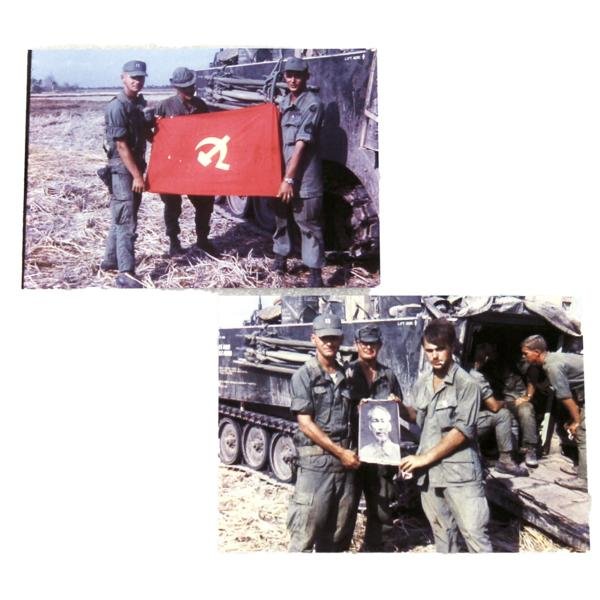

No shrine or war memorial has ever before attracted such unconventional and eclectic offerings. But no other war was fought in the context of the 1960s, when appearances and objects both acquired heightened symbolic meanings. The draft card, the black armband, and the white armband became icons; “in country,” GIs routinely individualized their uniforms and gear to denote affiliation—as in the slashed combat boots of a 1st Cavalry unit—or allegiance—as in peace symbols drawn across the backs of utility shirts.

Now the era’s cultural detritus appears at the wall like things washed ashore after years at sea. A working television set is left off one day, perhaps to signify the nation’s first televised war or perhaps just the property of some luckless draftee who never came home to watch it again. Like more than two-thirds of the objects left at the memorial, it arrived without explanation. “Everything is left for a reason, but unless you have a real understanding, it’s dangerous to interpret the objects,” Duery Felton says. He welcomes explanatory letters, and he seeks out help with unusual insignia, patches, and other military markings. He has learned the stories behind everything from Pan American “kiddie wings” to British sterling shaving kits.

But sometimes meaning remains in the eye of the beholder. In 1991 Felton teamed up with Jennifer Locke of the Smithsonian Institution, a child during the Vietnam War, to select items for a small exhibit at the Museum of American History. Felton, as Locke tells it, wanted to include a parking ticket, speculating that it bespoke the Vietnam veteran’s continuing problems with impersonal authority; Locke saw something that had fallen out of someone’s pocket. In the end the ticket didn’t make the final cut, but a pacifier did. “It could have been dropped by accident,” Locke says, “or it could have belonged to the child of someone who was killed in Vietnam.”

Before about 1985, when word began to spread that the things left at the memorial were being saved, most of what turned up was what Felton calls “pocketables—a beaded necklace or a swizzle stick—or “field expedients”—two cigarettes made into a cross. Subsequently, many of the offerings began to look more elaborate and premeditated. The word processor took over from the scrawled note, the prepared work from the found object. Donors often alerted the National Park Service before relinquishing objects of value at the memorial.

Leaving something behind began to be a standard ritual for a visit to the wall. At the same time, there came to be more participation by visitors who had no close connection to anyone named on the wall. Boy Scout troops left wreaths for hometown heroes; a German sailor penned an antiwar message on his white cap. Offerings unrelated to the war accumulated. A twisted scrap of gray metal appeared one day; the donor explained that it was wreckage from a B-52 that had crashed in Kentucky in 1959, killing his father. Someone else left two large crystals wrapped in blue velvet—a “psychic guide” for the collection’s keepers.

Donors who came neither to mourn nor to commune with their own dead were helping to turn the memorial into a bulletin board, and like all bulletin boards, the memorial began to attract its share of advertising. The director of the radical antiabortion group Operation Rescue has left his business card, and so have politicians, psychotherapists, and business owners.

As a public forum the wall began early on to attract social and political discourse beyond the war’s immediate range. A Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military service award, was returned by a Vietnam veteran with a letter that began:

Dear President Reagan,

The enclosed statement of my renunciation of the Congressional Medal of Honor and its associated benefits represents my strongest public expression of opposition to U.S. military policies in Central America. You have been the champion of these brutal policies. I hold you most responsible for their origin and implementation.

For their part, Ronald and Nancy Reagan weighed in with a handwritten message at the wall:

Our young friends:

Yes young friends, for in our hearts you will always be young, full of the love that is youth, love of life, love of joy, love of country. You fought for your country and for its safety and for the freedom of others with strength and courage. . . .

More recently Operation Desert Storm yielded, among other things, a crop of yellow ribbons, a few signs that said NO BLOOD FOR OIL , and one that read GUYS, THIS TIME WE WON . Since then the tokens of major marches—pro-choice, pro-life, gay rights—have regularly lined the wall.

On Memorial Day 1993 the wreath that President Clinton laid at the wall had to be removed as soon as he finished his speech to escape destruction by hostile spectators. That Clinton’s behavior as a college student could still provoke such animus nearly a quarter-century later underscores the truism that Vietnam endures in extremely powerful ways. A great number of notes and tributes at the wall refer to veterans whose names do not appear there because they died not in action but years later, from the aftereffects of the herbicide Agent Orange or from posttraumatic stress disorder, both the subject of tireless veterans’ rights campaigns.

By far the most potent and enduring issue for some visitors to the wall has been the fate of those servicemen they believe are still held captive in Vietnam. Some thirteen hundred men are designated on the wall as unaccounted for, their names signaled by crosses. An unofficial, round-the-clock vigil for the missing, kept since Christmas Eve 1982, functions like a volunteer priesthood at the memorial. POW/MIA bracelets accumulate by the thousands, the objects most commonly left at the memorial.

The POW issue has been a powerful stimulant to the imagination. The redemption of the film hero John Rambo, a misfit veteran turned POW rescuer, has proved so resonant that the family of a real-life Rambo listed on the wall, Arthur John Rambo of Montana, had to appeal to the Park Service for help in halting all the rubbings being made of his name. More recently dog tags purportedly belonging to MIAs have been sold in Vietnam to veterans who later deposited them at the wall.

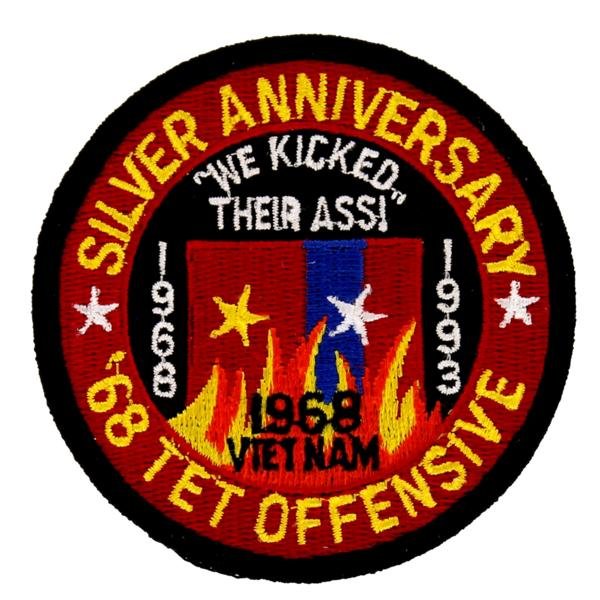

Wherever pilgrimages become popular, industries proliferate to make and sell devotional trinkets, and Duerv Felton has lately seen the same process at work at the wall. The cause, he believes, is the newfound prestige of the Vietnam veteran; the result, a boom in ersatz insignia, patches, uniforms, and other accouterments of the Vietnam grunt, including Zippo lighters newly “antiqued” in Vietnam. So the multitude of Vietnam experiences contained in the collection’s objects and words has come to include the pseudoexperience. But that makes sense. Pilgrimage sites are, in the words of the anthropologist Victor Turner, “cultural magnets, attracting symbols of many kinds.” They lie outside the normal bounds of society, where the real and the unreal can flourish side by side. Along with the pre-aged Zippos and the Rambo name rubbings, the wall has begun to attract fortyish nonveterans who arrive for holiday weekends fully arrayed in the uniforms of Vietnam service. Nearby the POW/MIA vigil draws clusters of fatigue-clad youths who never knew anyone listed as missing. Just beyond the memorial are trucks run by Vietnamese immigrants who sell hot dogs to former GIs. One senses, in all this, an attempt to close a circle around a reality still as elusive as Vietnam’s ever was.

For most people who regularly come to the memorial, the annual cycle of birthdays, holidays, and anniversaries defines an unrelenting reality: more than fifty-eight thousand deaths. (Vietnam puts its own dead at one million; its missing at three hundred thousand.) News of marriages, divorces, births, and deaths takes up the thread of narratives broken off a generation ago. On Father’s Day 1994 rangers picked up a double brass picture frame. One side held two blurry sonogram images; the other, a handwritten note:

Happy Father’s Day, Daddy.

Here are the first two images of your first grandchild. . . . Dad—this child will know you—just how I have grown to know and love you—even though the last time I saw you I was only four months old. . . .

Another letter accompanied a small handtinted photograph of a Vietnamese man and young girl:

Dear Sir,

For twenty two years I have carried your picture in my wallet. I was only eighteen years old that day we faced one another on that trail in Chu Lai, Vietnam. . . . So many times over the years I have stared at your picture and your daughter, I suspect. Each time my heart and gutts [ sic ] would burn with the pain of guilt. I have two daughters myself now. One is twenty. The other one is twenty-two, and has blessed me with two granddaughters. . . . Forgive me Sir, I shall try to live my life to the fullest, an opportunity that you and many others were denied.”

As curator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection, Duery Felton tries to keep his professional distance from the emotional content of the letters and mementos. He has, however, observed in them a tone of deepening continuity, as the Vietnam generation gives way to multiple generations. And they in turn show every sign of remaining part of a larger, ongoing Vietnam experience.