Her owner planned to take her from California to slave-holding Texas, so Biddy Mason went to court. After a dangerous drama, she won her freedom.

-

Winter 2023

Volume68Issue1

Editor’s Note: “The true-life story of women's experiences in the Wild West is more gripping, heart-rending, and stirring than all the movies, novels, folk-legends, and ballads of popular imagination,” says historian Katie Hickman, the author of nine books. So, she has compiled numerous such stories in her new title, Brave Hearted: The Women of the American West, from which this essay was adapted.

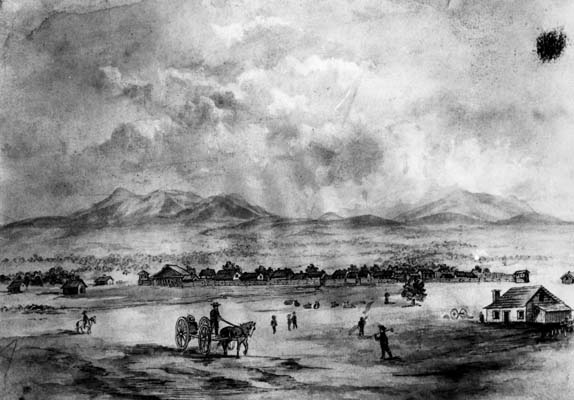

While many African Americans in the Old West, like General George Custer’s cook Eliza, lead peripatetic lives following the drum of the U.S. Army, others had already succeeded in making settled lives for themselves in the new territories of the West. California, particularly during the Gold Rush years, was considered “the best place for black folks on the globe” by one enthusiastic emigrant.

Unlike Oregon, California had not passed Black- exclusion laws, and many white Americans coming to California for the first time were confused by what appeared to them to be a lack of racial distinctions. California’s early political leadership included some men of African American ancestry — a legacy of the greater racial mix that had existed when California was still part of Mexico.

While the more fluid racial order that existed in California in the early years of its statehood did not last, and the specter of slavery was never quite eradicated until after the Civil War, it was in California that many African Americans would find their first, exhilarating tastes of freedom — and none more so than a remarkable woman named Biddy Mason.

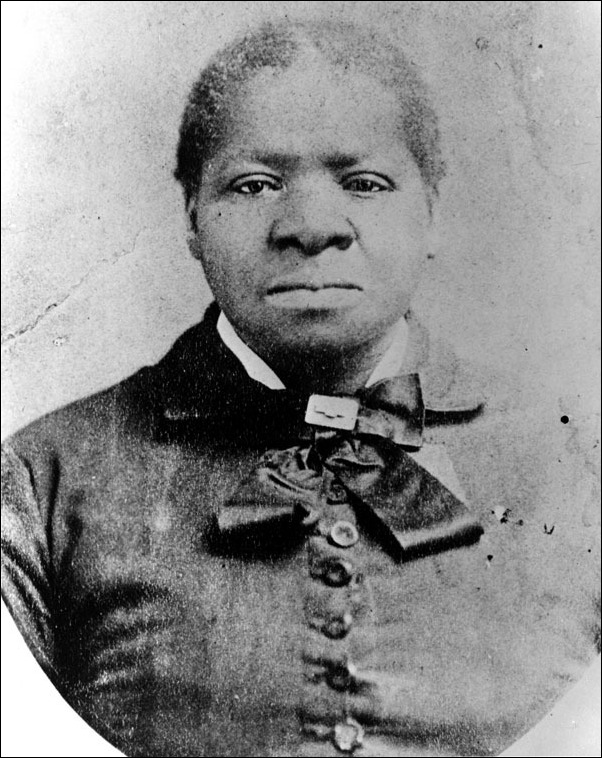

A black-and-white photograph of Biddy taken sometime in the 1870s shows her well into middle age: a small, homely-looking woman, she stares out at the camera with a strikingly level gaze. She wears a neat black dress, carefully buttoned up the front, with a satin bow at the neck, to which has been pinned a simple brooch. At the time this photograph was taken, Biddy Mason was a woman of substance.

Bridget (or Biddy) Mason had been among the very first African American women ever to make the journey west. By the time of her death in 1891, at the age of seventy-three, she was one of the most prominent and respected citizens in Los Angeles and a substantial property owner and philanthropist. First arriving in California in 1855, she was one of the first non-Mexican residents of Los Angeles, where she became a successful midwife.

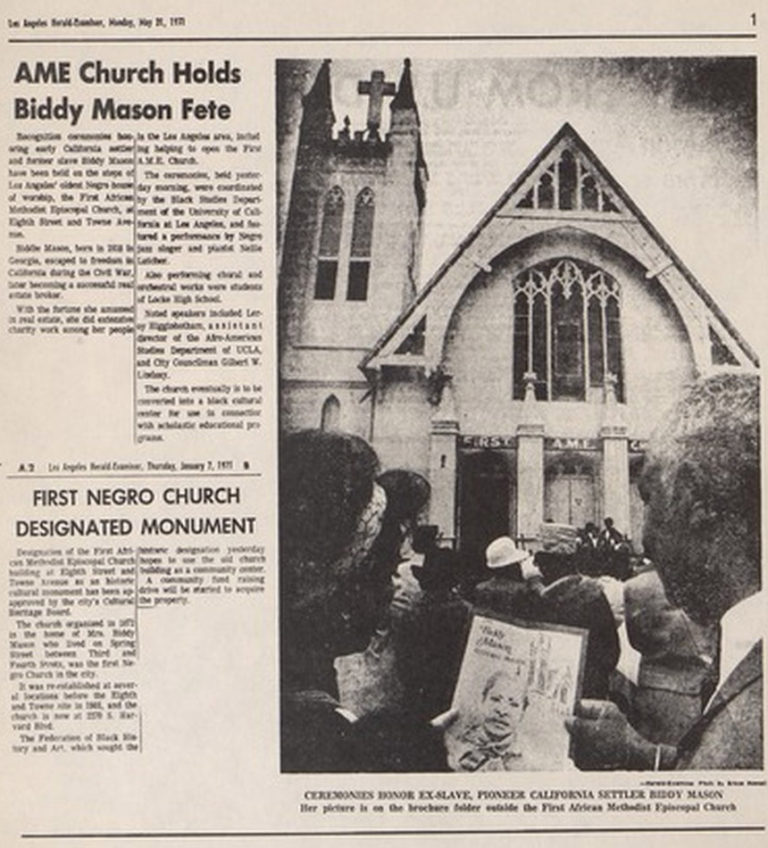

After ten years of working and saving, she had earned enough money ($250) to purchase land and build a home for herself and her family, becoming one of the first African American women to own property in her own right. She was also instrumental in setting up the Los Angeles branch of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, which had its inaugural meeting in her house. Those who knew her in her exemplary and prosperous later life would never have been able to guess at the bitter hardships she had endured.

Like many African Americans in the early years of the emigrations, Biddy Mason had first gone west as a slave. Born in Georgia in 1818, as a small child, she had been given as a wedding present to Robert and Rebecca Smith, the owners of a Mississippi cotton plantation. Biddy eventually bore three children, all girls — Ellen, Ann, and Harriet — very possibly the offspring of her owner, Robert Smith. Whatever the case, like Biddy herself, these children were Smith’s property and represented a considerable addition to the family’s wealth. Despite not being able to read or write, as a young woman, Biddy acquired a number of crucial skills. As well as working in her owner’s cotton fields, she learned how to manage livestock and became a skillful practitioner of herbal medicine. Robert Smith had a further six children with his wife, and Biddy often attended her during her confinements — an experience that would serve her well in later life.

Robert Smith was an early convert to Mormonism, and in 1848, he decided to take his family west, to follow Brigham Young’s call and help build the Kingdom of the Saints. On March 10, the Smiths joined forces with a party of Mississippi Mormons, a group of fifty-six whites and thirty-four slaves. In the Smiths’ party, there were nine whites and ten slaves. These included Biddy and her three children, one of whom she was still nursing, and another young enslaved African American woman, Hannah, who may have been Biddy’s half-sister and who was pregnant at the time.

Despite nursing a tiny baby and having two other young children to care for (Ellen and Ann were ten and four, respectively), Biddy was put in charge of herding the family’s livestock. This she did, for seven long months, on that arduous journey across the prairies and mountains to the desert salt flats of Utah.

Unlike the Pacific Territories (Oregon and California), both of which would go on to declare themselves free, Brigham Young’s desert kingdom enjoyed no such prohibitions. When the Smiths arrived in Utah, Biddy and daughters all continued in their household as slaves. Three years later, the Smiths decided to move again, this time to San Bernardino, California, where they hoped to help establish another Mormon colony. Despite warnings from Brigham Young that “there is little doubt but (the slaves) will all be free as soon as they arrive in California,” the Smiths made the decision to take their slaves with them. In 1851, these comprised an extended family of thirteen: Biddy and Hannah, who, between them, now had ten children, and one grandchild of Hannah’s, the child of her daughter, Ann.

In the same wagon caravan that left Salt Lake City for California, there were a number of other enslaved people, including Elizabeth Flake, a young woman who, like Biddy, had herded her owner’s livestock on the journey from the Mormon Winter Quarters (North Omaha) in Nebraska to Salt Lake City. The journey would prove life-changing for both young women. One of the teamsters on that journey was another African American, a former slave named Charles Rowan, and it is likely that it was Rowan, who would go on to be a prominent anti-slavery advocate, who first urged the two women to contest their enslaved status when they reached California. Elizabeth Flake, who did indeed become a free woman when she reached California, went on to marry Charles Rowan, and, like him, became a prominent member of the African American community in San Bernardino and also a vigorous abolitionist.

Biddy Mason, however, was not so fortunate. Like so many other slaveholders, Robert Smith had no intention of relinquishing his property.

Although under California’s new constitution, slavery was expressly prohibited, it did not follow that, on crossing the border, enslaved people such as Biddy and her family would automatically be free. Slaveholders who had arrived before 1850, when California gained its statehood, had been permitted to keep their slaves as indentured servants, but the reality was that many slaveholders simply ignored the law, which was considered by many to be unenforceable. Slaveholders either went unchallenged, or, if they were, the courts were overwhelmingly likely to favor their cause.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that, after several years of infighting, and as a concession to the southern slave states, in the same year that California became a free state, Congress had passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it easy to recapture escaped slaves. Bounty hunters who made a lucrative business of tracking down and capturing runaways (in much the same way that they were paid to collect Native American scalps, known as “hairy banknotes”) operated throughout California, often openly advertising in local papers throughout the 1850s. This created a bitterly fraught situation in which many African Americans, freed by their former masters, still faced persecution and harassment, in much the same way as they still did in Missouri River towns, such as Independence and Saint Joseph.

Throughout the 1850s, however, attitudes in California had begun, slowly, to change. Just two years after the Smiths’ arrival, a story appeared in the Alta California newspaper in which “a person by the name of Brown attempted to have a Negro girl arrested in our town a few days since as a fugitive slave, but was taken all aback by the girl’s lawyer, F. W. Thomas, producing her Freedom Papers. Brown’s father set the girl at liberty in 1851, and it is thought by many that the son knew the fact, and thought to catch the girl without her Freedom Papers, but fortunately for her, he did not.”

Sensing that there was trouble ahead for him if he remained in California, in late 1855, Robert Smith decided to move his entire family to Texas (which, like all the other southern states, would remain a slave state until after the Civil War). Any hopes that Biddy may have had of eventually gaining her freedom in California now seemed utterly dashed. While slaves in California were free by law, it was impossible to be free and black in Texas, since Texas law forbade the importation of free Blacks into the state, and Texans would have regarded them as slaves.

Against all the odds, Biddy now found herself with two powerful allies. One of these was Elizabeth Flake; the other was another African American called Robert Owens. Owens was, by all accounts, a formidable man, a former slave who had come to California from Texas in 1850, driving an ox team. At the time he came to champion Biddy Mason, just five years later, he was already a highly successful businessman, a horse and mule trader who ran a thriving corral in Los Angeles, employing ten vaqueros.

Robert and his wife Minnie Owens had a particular interest in Biddy’s case. Their son Charles was in love with Biddy’s daughter Ellen, now seventeen, and wanted to marry her. A third man, Manuel Pepper, possibly one of Robert Owens’s vaqueros, was in love with Hannah’s daughter, Ann, a young woman of the same age.

Although time was running out, there was now a small but critical delay to Smith’s plans to spirit his slaves away. Hannah was about to give birth to her eighth child, and the Smiths were camped out in a canyon in the Santa Monica Mountains, impatiently waiting for her confinement, after which she would be able to travel again. During this time, Elizabeth Flake and Robert Owens petitioned the local court for a writ of habeas corpus for Biddy and her family. In what must have been a moment of heart-stopping tension, a posse of mounted men—two county sheriffs, together with Robert Owens and his vaqueros—“all swooped down on the camp in the mountains and challenged Smith’s right to take his slaves out of California.”

Biddy and her family were taken to the county jail, where they were put “under charge of the sheriff of this county for their protection,” until their case would be heard.

It is almost impossible to imagine the courage that was now necessary. Although she was a mature woman of thirty-eight, until this point in her life, absolutely everything that Biddy Mason had ever known would have militated against taking such a step. Slaves were the absolute property of their owners.

While laws varied across the southern slaveholding states, all followed a similar pattern. Slaves were forbidden from congregating together, even for religious worship, without white supervision. They were forbidden from bearing arms and marrying or traveling without the written permission of their masters. They could own no personal property, sometimes including even their working tools or the clothes they wore. Most crucially, perhaps, they were forbidden from learning how to read or write.

In Virginia, the cotton-planting region where the majority of African Americans lived, slave literacy was a criminal offense. In Virginia, also, even free Blacks were prohibited from trying to educate themselves, and if a free Black left the state to be educated elsewhere, she or he was barred from ever returning. Most egregious of all, in Kentucky, it was a criminal offense for African Americans to try to defend themselves, no matter what the circumstances, against white assault.

Slaves and any children they might have could be bought and sold, either together or separately, at the will of their owners, who often split families apart with impunity; they could be given away in lieu of debts and left in wills as part of their owner’s estate. It goes almost without saying that their testimony was worth nothing in a court of law.

What's more, if Biddy Mason’s case had come to trial just a year later, she would have lost her case outright. In 1857, in the notorious Dred Scott decision, the US Supreme Court ruled that a slave was not a person, but property, and that a slave’s residence in free territory, or in a free state, did not make that individual free.

It is hard to imagine what Biddy Mason might have been feeling as she looked out through the bars of the jail, contemplating the prospect of having to face her owner, Robert Smith, in court. One thing she would have known, with absolute numbing certainty, was that, if she lost her case, the consequences for her and her children would be catastrophic.

It is, on the other hand, absolutely clear what Robert Smith felt. The entire case that he put forward through his lawyer, Alonzo Thomas, was shot through with lies. First, he tried to argue that the petitioners were members of his family, denying outright that he was holding them as slaves. They had come with him from Mississippi to California, he argued, “with their own consent, rather than remain there, and he (had) supported them ever since, subjecting them to no greater control than his own children.” It was his intention, he stated, “to remove to Texas and take them with him.”

The situation for Hannah was more dangerous still. Unlike Biddy, who had been immediately taken into protective custody, the recently confined Hannah and her newborn baby had remained with the Smiths. They were therefore not only physically under his control, but highly vulnerable to his threats and intimidation. In the case put forward by his lawyer, Smith argued that Hannah and her children were “well disposed to remain with him, and the petition was filed without their knowledge and consent.” His lawyer added: “It is understood, between said Smith and said persons, that they will return to the State of Texas with him voluntarily, as a portion of his family.”

The trial, which was reported, in all its painful details, in the Los Angeles Star, took place between January 19 and 21, 1856. Presiding over the case was Benjamin Hayes, judge of the District Court of the First Judicial District, Los Angeles.

In his summation, the judge set out the situation with great clarity. Robert Smith, he declared, “intended to and is about to remove from the State of California, where slavery does not exist, to the State of Texas, where slavery of Negroes and persons of color does exist, and is established by the municipal laws, and intends to remove the said before-mentioned persons of color, to his own use without the free will and consent of all or any of the said persons of color, whereby their liberty will be greatly jeopardized, and there is good reason to apprehend and believe that they may be sold into slavery or involuntary servitude.”

Robert Smith, he noted, “is persuading and enticing and seducing said persons of color to go out of the State of California, and it further appearing that none of the said persons of color can read and write, and are almost entirely ignorant of the laws of the State of California, as well as those of the State of Texas, and of their rights and that the said Robert Smith, from his past relations to them as members of his family does possess and exercise over them an undue influence in respect to the matter of their removal, insofar that they have been in duress and not in possession and exercise of their free will so as to give a binding consent to any engagement or arrangement with him.”

The necessarily dry legalese with which Judge Hayes gives his verdict in the case of Mason v. Smith conveys little of the febrile atmosphere in and around the court on that day. The article in the Los Angeles Star, on the other hand, gives an eyewitness account of the extraordinary, nail-biting human drama.

Perhaps sensing that the case was going to go against him, Robert Smith had tried various other tactics. First, he had attempted to threaten Biddy and Hannah outright, and when that did not work, he proceeded to bribe their lawyer with one hundred dollars (a huge sum) to drop the case. Their lawyer (unnamed in the Star article) accepted the bribe. Just one day into their trial, the two women found themselves completely abandoned in the courtroom. Under California law, Blacks, “Mulattoes,” and Native people were all prohibited from testifying against whites, in either civil or criminal cases.

Without a lawyer, they did not stand a chance.

But Robert Smith had not reckoned with Judge Hayes. “I was pained by an occurrence not to be passed unnoticed,” the judge wrote. “There was a motion to dismiss the proceedings, based on a note from the petitioners’ attorney on the opposite side, in these words: ‘I, as attorney for the petitioners, being no longer authorized to prosecute the writ, and being discharged by the same and the partner who are responsible to me, decline further to prosecute the matter.’”

Judge Hayes subpoenaed the lawyer, questioned him, and then denounced his lack of legal propriety. He then proceeded to question the women, not in court, but in his private chambers. In addition to Judge Hayes himself, two disinterested “gentlemen witnesses” were present to hear their story. The conversation was reported as follows:

Biddy: “I have always done what I have been told to do; I always feared this trip to Texas, since I first heard of it. Mr. Smith told me I would be just as free in Texas as here.”

Hannah’s daughter, Ann, when questioned separately from Biddy, asked the judge, “Will I be as free in Texas as here?”—a question the legal experts found a poignant response to Smith’s bluster that all would travel willingly.

It would transpire later that Robert Smith had employed not only verbal threats but other, even worse forms of intimidation to try to force the women to give up their case. One of the Smith party, a man named Hartwell Cottrell, made a bungled attempt to snatch two of Hannah’s children away from her, and he had to flee California to avoid being prosecuted.

The turnkey at the county jail, Frank Carpenter, later gave evidence in court as to the women’s terror of Smith, but, even without his testimony, it was perfectly clear to everyone in court. The judge decided that the “speaking silence of the petitioners” must be listened to, and that Hannah, in particular, had almost certainly been threatened. “Nothing else — except force — can account rationally for a favorable disposition in Hannah, if she had any.” Her very hesitation in speaking out, he noted, “spoke a volume,” and furthermore, “she is entitled to be listened to when, breathing freer, she declares she never wished to leave, and prays for protection.”

In his conclusion, Judge Hayes wrote: “No man of any experience in life will believe that it was ever true, or ever intended to be realized — this pleasant prospect of freedom in Texas.” Robert Smith, he observed, had only “$500 and an outfit” and had “his own white family to take care of, and seemed to have no reason to transport fourteen slaves so far — unless he intended to sell them.”

“And it further appearing . . . to the judge here, that all of the said persons of color are entitled to their freedom and cannot be held in slavery or involuntary servitude, it is therefore argued that they are entitled to their freedom and are free forever.”

Excerpted from BRAVE HEARTED: The Women of the American West by Katie Hickman, © 2022, published with permission from Spiegel & Grau.