How tough Henry Knox hauled a train of cannon over wintry trails to help drive the British away from Boston

-

April 1955

Volume6Issue3

Knox was one of those providential characters which spring up in emergencies, as if they were formed by and for the occasion.

—Washington Irving, Life of George Washington.

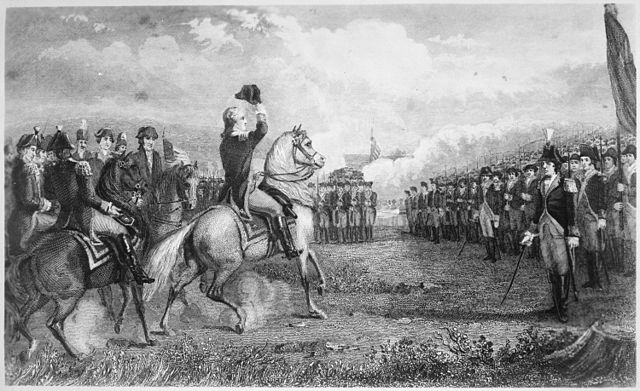

By the time Washington took command of the American Army at Cambridge in July, 1775, his troops had dug fortifications on the hilltops ringing Boston. The British, who had occupied the city for over a year, were pinned down but could not be starved out as long as their navy kept the port open. The Americans lacked siege guns and trained storm troops. On the other hand, General Gage, the British commander, had been made cautious by the mauling his infantry had received on the Concord expedition and at Bunker Hill.

American artillery could threaten British shipping only on one of the two heights situated at opposite tips of the crescent formed by the American lines: Bunker Hill, north of Boston, and Dorchester Heights, across the bay to the southeast. Bunker Hill had been won by the British and neither side was yet ready to fight for Dorchester Heights—the British because of Gage’s reluctance to risk the loss of more troops difficult to replace; the Americans because they lacked the artillery to take advantage of the superior location once it had been occupied.

The military situation had reached a frustrating stalemate. In keeping secret his shortage of arms and powder, Washington had divested himself of any ostensible reason, in the eyes of his men and the Continental Congress, for not taking Boston. His troops, after all, outnumbered the British better than two to one. The inactivity was fomenting low morale and wholesale desertions. In a few months, the year’s enlistment period would be up for Washington’s army and the straws in the wind were enough to inform him that there would be few soldiers who would remain for a second hitch. Supplied with artillery, he could quickly place the guns within effective range of the British land defenses and naval vessels and drive Gage out of Boston.

Where were enough artillery pieces to be obtained? Even if they could be spared from defense points elsewhere in the colonies, the logistical problem of transporting them in time and in sufficient number to be worthwhile could not be overcome.

Washington’s answer came from one of the few men he had come to like, trust and respect since the general’s arrival in Cambridge: Henry Knox, a civilian volunteer, a bookseller.

Knox was a native of Boston. His parents were Scotch-Irish who had emigrated from northern Ireland. The elder Knox was a ship’s master who died bankrupt in the West Indies when Henry was twelve. Henry was the seventh of ten sons and one of only four to survive childhood. Of these four, the two eldest were lost at sea, leaving only William, the youngest, and Henry.

The support of his mother and six-year-old brother fell upon Henry Knox when he was twelve. He left school reluctantly, but went to work in a Boston bookshop where he was able to continue reading on company time. A military enthusiast, he joined the provincial militia, an artillery group trained by British officers, and read books on martial subjects. Knox opened his own bookstore in 1771, in the midst of the growing storm of the approaching Revolution, continuing to import his literary stock from London.

Knox was a huge man, and his large frame supported his 250 pounds strikingly. He had charm, poise and a forceful personality. By romantic standards, it was quite understandable that Lucy Flucker, daughter of the royal secretary of the province, should not only fall in love with Knox but, having married him, should willingly adjust her politics to fit his when war began and her loyalist family was forced to flee Boston with General Howe. An enthusiastic huntsman, Knox lost two fingers of his left hand when his fowling piece exploded during a hunt on Noddle’s Island in 1773.

General Gage took over the military occupation of Boston in 1774, the year Henry was married to Lucy. Knox, along with Paul Revere and other local tradesmen, belonged to the intelligence committee which watched and listened and kept such colony spokesmen as John Hancock and Sam Adams informed as to British movements and intentions. Knox was known to the British as a colonial sympathizer and hence was forbidden to leave Boston. He and his wife, therefore, left the city secretly the day after the battle of Concord, leaving his bookstore to the management of his brother, William. The store was looted and wrecked almost immediately and there was nothing for William but to join his elder brother in Worcester, where Knox had taken Lucy.

General Artemas Ward was in command of the New Englanders surrounding Boston and Knox volunteered as an artillery expert without rank. He was assigned to supervising the construction of fortifications then being dug above Boston. His accomplishments moved Washington, after that gentleman had taken command in July, to write glowingly of Knox to the Connecticut governor.

The artillery command belonged to an aged and infirm veteran of the French and Indian War, Richard Gridley, and Washington, less than a month after he had arrived in Cambridge, wrote the president of the Continental Congress that Gridley should be replaced. “Knowing no person better qualified to supply his place,” Washington wrote, “or whose appointment will give more general satisfaction, I have taken the liberty of recommending Henry Knox to the consideration of Congress.”

To Washington, artillery was the all-important element. He was impressed by Knox’s perpetual optimism in the face of a gloomy predicament and by the large man’s resourcefulness in ideas. Nor did Knox let the general down. One day he suggested to Washington that the cannon captured at Fort Ticonderoga the previous May might be sledded and floated the 300 miles to Cambridge that winter and be available for use against the British the next year, 1776. Washington at once endorsed the proposal, adding that “no trouble or expense must be spared to obtain them.”

Knox, then 25 years old, left for New York in late November, taking with him his brother William. They took a boat up the Hudson to Albany where, on December 1, Knox reported to General Philip Schuyler, commander of the northern armies. Schuyler had been instructed by Washington to help Knox in his venture in every way possible and the major general willingly arranged for Knox’s transportation to Ticonderoga and promised to help with the problems of transporting the heavy ordnance on the later trip across the mountains into Massachusetts.

The severity of the early winter is known from a diary of the trip sketchily kept by Knox. He and William reached Ticonderoga four days later, riding on rutted, frozen roads to Fort George, at the southern end of Lake George, and by boat to Fort Ticonderoga.

Ticonderoga stood where Lake George empties into Lake Champlain and where opposite land juttings squeeze Champlain’s width to a quarter-mile. The fort occupied the western headland. It had figured prominently in the French and Indian War when it was held by the French as Fort Carillon. Montcalm had held it against the British in 1758 but the next year Lord Jeffrey Amherst had taken it from the French. Amherst had blown up the defenses and retired, but later the British rebuilt it and named it Ticonderoga. With the conclusion of that war, leaving French Canada in English hands, there was no Canadian border to maintain; the fort became more of a settlement, meagerly staffed and used as a supply post. Ethan Alien was encouraged by the colonists to take it to protect their rear from an attack by a Canadian force. In executing this assignment Alien’s forces, with Benedict Arnold, had also captured guns and boats at nearby Crown Point.

Much of the captured artillery at Ticonderoga was too worn to be of use, but 78 pieces were salvageable, ranging from 4-pound to 24-pound guns, as well as six mortars, three howitzers, 30,000 flints, and tons of muskets and cannon balls. A rare prize, indeed, if the ponderous equipment could be dragged over the Berkshires and across the length of Massachusetts before a spring thaw sabotaged the effort.

Knox at once dismantled nearly sixty cannon and lowered them from their lofty wall emplacements to the ground where they were carted across a swampy, wooded peninsula by the colonist garrison and loaded into three boats: a scow, known as a “gondola,” a bateau, which to French Canadians and Louisianians meant a flat-bottomed boat with tapered ends, and what Knox in his diary called a pettiauger .

Leaving William in charge of the heavily-laden craft, Henry hurried ahead in a lighter, faster bateau, in order to get together all the oxen, horses and sleds necessary for the next part of the trip back to Boston.

Navigating 33-mile Lake George with this priceless cargo was a breath-taking enterprise. The lake, which at its widest is only three miles across, was forming ice on either side a mile from shore. A favorable wind died almost immediately. The scow ran on a sunken rock and William managed to free it only to have the unmanageable craft go aground in earnest at Sabbath Day Point, not halfway down the lake. The damage this time was so substantial that the guns had to be unloaded from the scow and some added to the other boats, already low in the water from their loads of lead, brass and iron. Eventually, the guns arrived at Fort George without a loss.

Henry and his crew had been fed and warmed their first night on the lake by friendly Indians at Sabbath Day Point, but the next day they ran into a headwind which forced them to row desperately for ten hours to make Fort George.

Hurrying on alone by land in the attempt to beat the arrival of heavy snow or to take advantage of any normal snowfall, Knox arrived at Oscillate, two-thirds the distance between Fort George (now the village of Lake George) and Albany, to obtain animals and sleds from Squire Charles Palmer, whose assistance in the matter had been assured. Returning to Fort George, thus supplied in part, Knox had an additional 42 heavy sleds made and finally collected eighty oxen for the big pull south to Albany. Schuyler, meanwhile, had dispatched men and horses from Albany and Saratoga to help Knox through the foothills of the Adirondacks.

Knox had written Washington from Fort George on December 17: “The route from here will be to Kinderhook [New York] from thence to Great Harrington [Mass.] and down to Springfield. I ... expect to move them to Saratoga on Wednesday or Thursday next, trusting that between this and then we shall have a fine fall of snow, which will enable us to proceed farther, and make the carriage easy. If that shall l)e the case, I hope in 16 or 17 days’ time to be able to present to your Excellency a noble train of artillery.”

Knox was an eternal optimist. But in following the rude woodland roads south to Albany he believed he would have to cross the unreliably frozen Hudson four times, although actually he had to cross it but once and the Mohawk once. At Albany, a thaw for a time prevented his crossing to the east side at all. Where open water confronted the teamsters, it was necessary to load sleds, guns and horses into scows for the crossing. Where the ice was too thin to support the train but too thick to permit boat passage, Knox was helpless. He frequently had to cut holes in the river’s ice in order for the overflow of water to freeze and add to the ice’s thickness.

John P. Becker, a twelve-year-old lad from Old Saratoga, who served with his father as a driver for Knox on the trip from Fort George to Springfield, Massachusetts, has left an account of the trip, which was first published in the Albany Gazette in the 1830’s.

“We felt an unusual degree of interest in fulfilling our contracts,” Becker remembered. “My father took in charge a heavy iron nine pounder, which required the efforts of four horses to drag it along. Others had the heavy resistance of 18’s and 24’s to overcome, which required the exertions of at least 8 horses. We had altogether about 40 or 50 pieces to transport, and our cavalcade was quite imposing.”

At Lansing’s Ferry, near the mouth of the Mohawk River, the cavalcade tried to cross on the ice to the east bank of the Hudson. As a precaution, a 40-foot rope was tied to the first sleigh tongue and a teamster walked alongside with a hatchet, ready to cut the rope and save the horses should the heavy gun crash through the ice. Halfway across, the ice did give way, “and a noble 18 sank with a crackling noise, and then a heavy plunge to the bottom of the stream.” The water fortunately was shallow and the gun was recovered. The crossing at that point, therefore, was abandoned. Back tracking, the train finally crossed the Mohawk at Klaus’s Ferry on thin ice, remaining on the west side of the Hudson until Albany. One cannon was lost in the Mohawk and left there. Recovered much later, it is now at Fort Ticonderoga.

The first cannon, a brass 24-pounder, reached Albany on January 4, 1776, somewhat behind Knox’s schedule. Within three days the remainder of the guns had entered Albany for the final crossing of the Hudson. “Our appearance excited the attention of the burghers,” Becker wrote. “... This was the first artillery which Congress had been able to call their own, and it led to reflections not in the least infurious to our cause.”

Knox hired some of the interested “burghers” at the pay of “one and four pence a mile, and, when . . . detained by breakages or other accidents . . . 15 shillings a day.” Knox wrote Washington a pained letter on January 5, while waiting for the ice to thicken at Albany: “The want of snow detained us for some days, and now a cruel thaw hinders from crossing the Hudson River . . . The first severe night will make the ice sufficiently strong; till that happens, the cannon and mortars must remain where they are. These inevitable delays pain me exceedingly.”

Eventually the freeze arrived and Knox’s artillery train streamed across the Hudson. Continuing south, Knox arrived at Claverack, where a broken sleigh detained him for two days. The need for plenty of able-bodied help in case of a mishap prompted Knox’s policy of delaying the entire column if but one of its components got into trouble.

At Claverack, Knox took the hazardous military trail used by only a few others, which headed east over the Berkshires, through Great Barrington, Otis and to Springfield on what is now Route 23, a treacherous road for motorists even today. Using eighty oxen again in place of horses, Knox wrote, “We reached No. 1 [referring to Monterey, Mass.] after having climbed mountains from which we might almost have seen all the Kingdoms of the Earth.”

Plunging into a twelve-mile stretch called “Greenwoods,” made dreary and forbidding by dense evergreen forests, Knox passed through what is now East Otis and reached Blandford, where more trouble awaited him. The descent of Glasgow (now Westfield) Mountain had to be made. It required three hours of arguments by Knox to assure the Hudson Valley teamsters that the treacherous trip down could be made without danger from runaway, weighted sleds plummeting downhill upon them. Knox supervised the precautionary measures taken, such as drag chains, poles thrust under runners, and check ropes anchored to one tree after another.

By January 14, the train lumbered into Westfield. Knox’s diary had by now ended, but Becker, who was still along, later continued the eyewitness account: “Our armament was a great curiosity [in Westfield]. We found that few, even among the oldest inhabitants, had ever seen a cannon . . . We were great gainers by this curiosity, for while they were employed in remarking upon our guns, we were, with equal pleasure, discussing the qualities of their cider and whiskey.”

At an inn that evening, Knox was surrounded by local visitors, all of whom seemed to be officers in the militia. “What a pity,” Knox told an associate, “that our soldiers are not as numerous as our officers.”

At Springfield there was the broad Connecticut River to cross. The ice held, but on the far side the “noble train of artillery” bogged down in the mud of a sudden thaw. Knox paid off the drivers from New York State there and hired native teamsters. When the ground froze again he pushed on. At Framingham, he temporarily deposited most of the heavier pieces in order to rush the more portable cannon to Washington at Cambridge.

Back in camp, Knox learned that the colonists had accidentally acquired plenty of ammunition to fit his guns, thanks to an American warship which had captured the British supply brigantine, Nancy , and had salvaged her cargo of powder and shot.

Knox’s artillery began a bombardment of Boston on March 2, 1776, and Washington moved men into Dorchester Heights in preparation for cannon installations there. The British didn’t wait for these to materialize. General Howe (Gage had been recalled some months before) made halfhearted plans for taking the heights and then decided instead to evacuate the city. He threatened to burn Boston if his embarkation was molested by Knox’s artillery and, on this unpleasant note, took his departure practically undisturbed. This was on March 17, which is observed annually in Massachusetts by a proclamation by the governor.

Knox’s own modest estimate of his remarkable achievement in those desperate winter months of 1775-76 is possibly reflected accurately in the simple memorandum of expenses he submitted at the conclusion of the arduous venture: “For expenditures in a journey from the camp round Boston to New York, Albany, and Ticonderoga, and from thence, with 55 pieces of iron and brass ordnance, 1 barrel of flints, and 23 boxes of lead, back to camp (including expenses of self, brother, and servant), £520.15.8¾.”

By standards of military supply in any age, this amount (some $1,458.20 in modern currency) charged the Continental Congress in exchange for Boston, must represent a model instance of government spending.