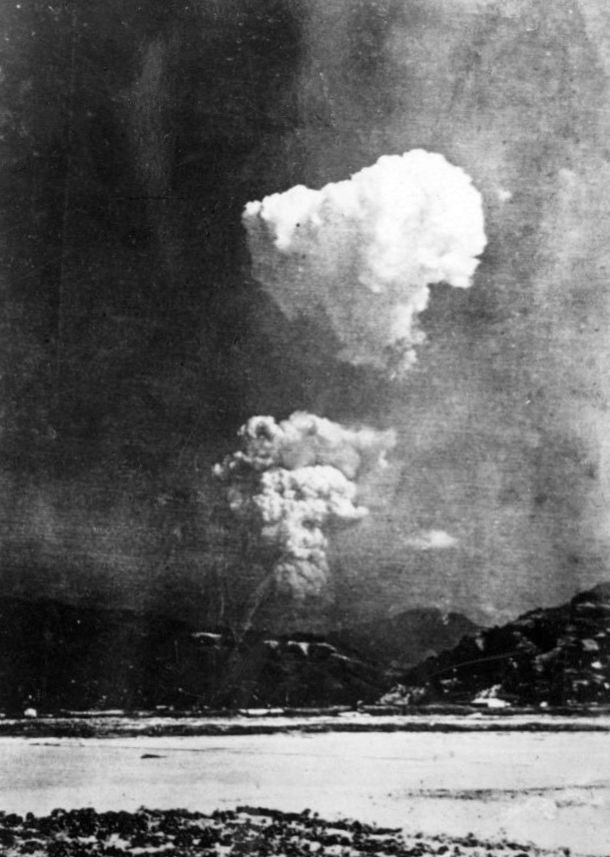

American leaders called the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki our 'least abhorrent choice,' but there were alternatives to the nuclear attacks.

-

August 2023

Volume68Issue5

In the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing, American consciences were settled: the weapon had avenged Pearl Harbor and Japanese atrocities such as the Bataan Death March, avoided a land invasion, saved hundreds of thousands of American lives, and ended the war. The targets were “military,” Washington repeatedly assured the public. The media caressed the bomb as the savior of mankind – only 1.7 percent of 595 newspaper editorials in 1945 opposed the use of the atomic bomb.

The press and public mutually reinforced their satisfaction at a job well done. Asked whether they approved or disapproved of the atomic strikes, 85 percent of Americans said in a Gallup Poll on August 26, 1945 that they approved. The responses of men and women, young and old, middle- and working-class, fetched the same result.

Curiously, 50 per cent of Americans said, in the same poll, that they were against the use of poison gas – even if gassing the Japanese would have reduced American casualties. The reasons were possibly connected with the ghastly memory of mustard gas used in World War I and the emerging horror of the Nazi death camps and gas chambers.

Atomic bombs were seen as spectacular new weapons that somehow inflicted a cleaner, quicker death. That perception gradually cooled as the public learned the truth about the destruction of civilian life and the facts of radiation poisoning; two years after the war, the number who approved of the bomb was cut in half, according to a similar poll.

Letters to the editor in August 1945 in America and Britain conveyed the full range of feelings, from ardent approval of the weapon to moral outrage at the wanton destruction of civilian life. The Times in London registered the angst of clergymen, politicians, and artists. There were soul-searchers – “Shall we not lose our souls in the process of using these new bombs?”; those who were disgusted – “A few months ago, we were expressing horror at the inhumanity of the Germans’ use of indiscriminate weapons ... Must we not therefore now apply this criticism to ourselves?”; pulpit- pounders – The bomb, claimed Sir William Beveridge, had “obliterated” any distinction between combatants and civilians as targets of attack, and had exacted too great a price for peace; and there was George Bernard Shaw, who wrote, “We may practice our magic without knowing how to stop it, thus fulfilling the prophecy of Prospero.”

Prince Vladimir Obolensky, a Russian aristocrat then living in London, challenged the emerging consensus that the bomb “brought the Japanese war to a magic end,” as he wrote in The Times in late August of 1945: “The belief that it has saved millions of the allies’ lives is a misconception ... In reality, Japan has been brought down by the interruption of her sea communications by Anglo-American air and sea power, and the danger of a Soviet thrust across Manchuria, cutting the Japanese armies in Asia off from home.”

The bomb provoked extreme reactions among American church leaders: provincial firebrands extolled atomic power as a heavenly thunderbolt with which the Almighty had endowed His American disciples to smite the wicked – echoing Truman’s description of the bomb as the “most powerful weapon in the arsenal of righteousness.”

Many religious leaders, however, quietly registered their Christian disapproval of the mass killing of noncombatants. This intensified as the truth about the effects of the bombs emerged. The Federal Council of Churches was among the most vociferous, branding the atomic bombing of Japan “morally indefensible;” America had “sinned grievously against the law of God and the Japanese people.” The sermon jarred in a country where most people despised the Japanese and believed in God.

Several church leaders condemned the bombings as war crimes. On August 29, an influential magazine, The Christian Century, published an article headlined, “America’s Atomic Atrocity,” which strummed the nerve of moral outrage and provoked a stream of letters that shared the author’s revulsion at America’s impetuous adoption of “this incredibly inhuman instrument:” the atomic bomb had placed the United States in “an indefensible moral position,” the magazine concluded, and the editors landed the blame squarely on the shoulders of the US government and, by extension, the American people.

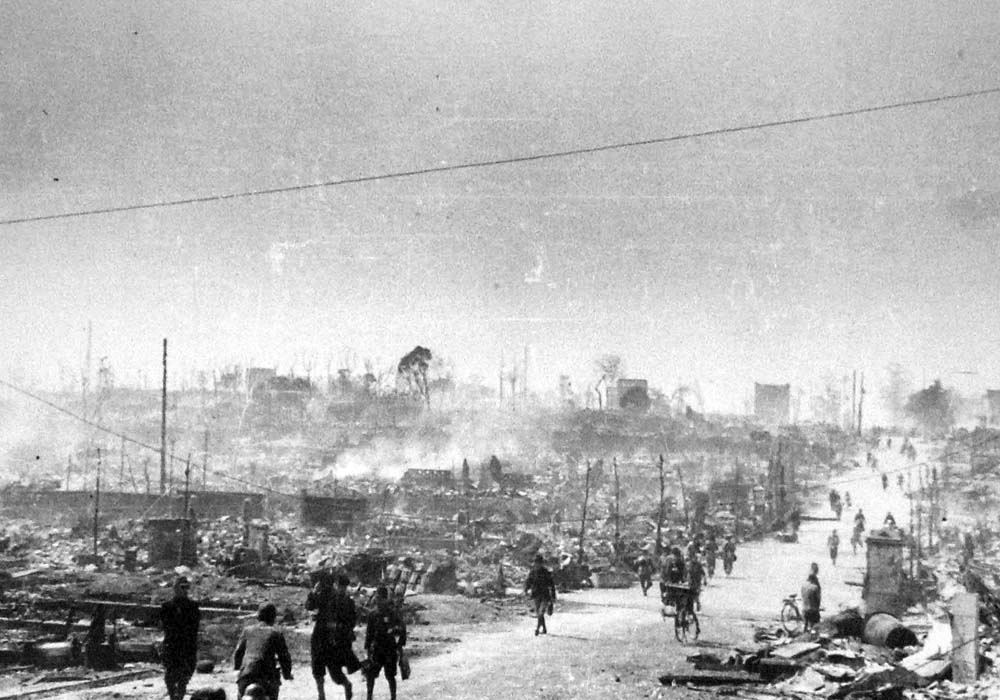

It was a collective crime against humanity: we dropped the bomb on “two helpless cities;” we destroyed more lives than the US lost in the entire war; we crippled America’s reputation for defending justice and humanity. The Christian Century’s philippic ended with an appeal to Nagasaki’s devastated Catholic community for understanding and forgiveness, and a rallying cry to action: “The churches of America must dissociate themselves and their faith from this inhuman and reckless act of the American government ... They can give voice to the shame the American people feel concerning the barbaric methods used in their name.”

And, despite Harry Truman’s efforts to appease the Holy See, the Vatican’s disgust presaged a long accretion of Catholic condemnation. Father John Siemes, a priest who experienced Hiroshima, alerted the Vatican to the horror on the ground: “The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have a material and spiritual evil ... which far exceeds whatever good might result?”

The Vatican, by its actions, concurred. Leaders of the Anglican Church shared that sentiment. The Dean of St. Albans, England, refused a service to commemorate victory in the Pacific because “victory was clinched by the atomization of a quarter of a million Japanese.”

As the facts of the destruction filtered back to Los Alamos in August and September, the earlier exuberance of the Manhattan Project’s scientists and engineers turned introspective and, by stages, morose. The “questionable morality’” of dropping the bomb without warning “profoundly disturbed” many, and their qualms deepened after Nagasaki, observed Edward Teller: “After the war’s end,” he wrote, “scientists who wanted no more of weapons work began fleeing to the sanctuary of university laboratories and classrooms.”

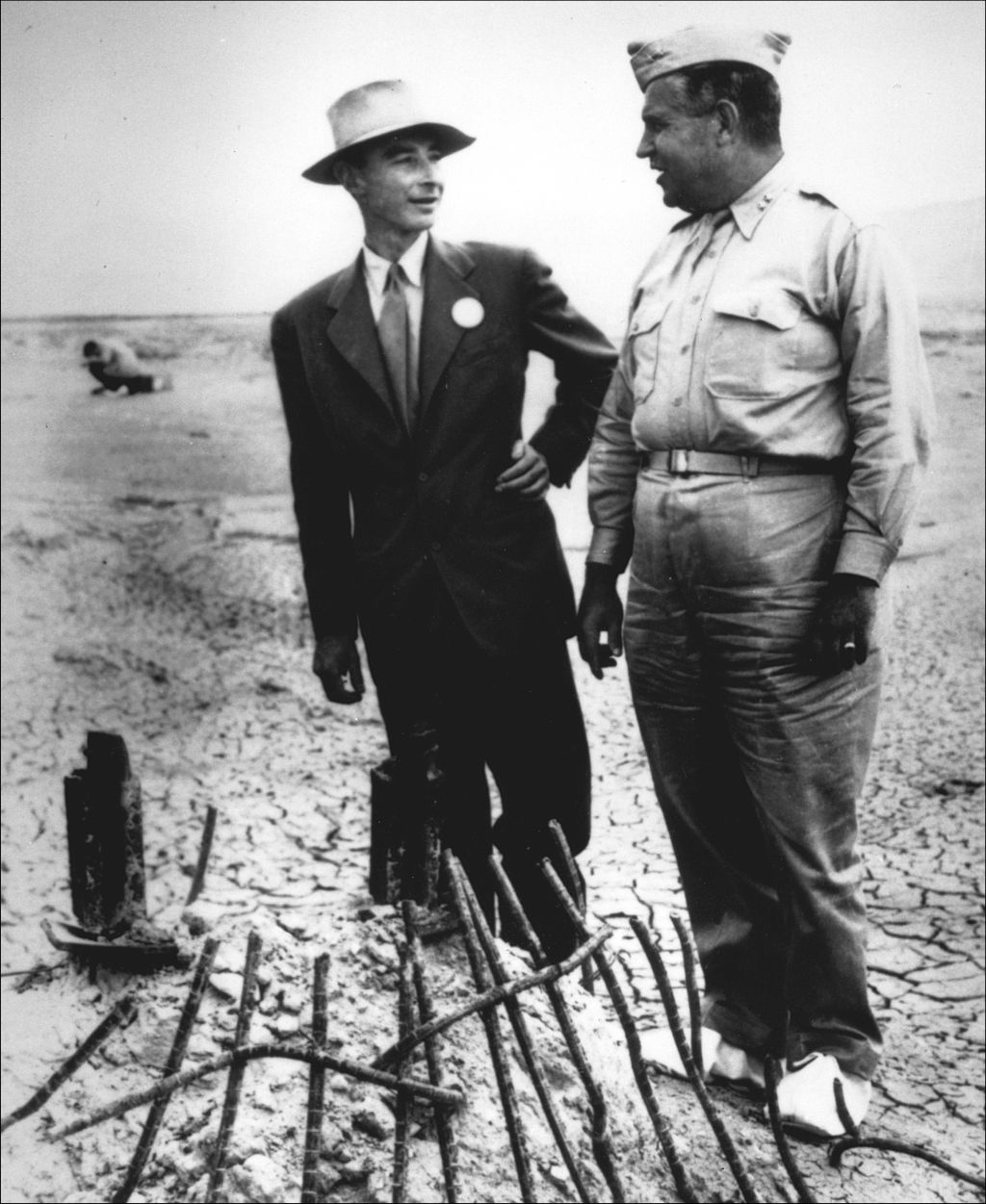

In Robert Oppenheimer, we encounter a man who seemed to reflect the median temperament, rather like a psychic bellwether. On October 16, his last day on the “Hill,” Los Alamos held a farewell ceremony in his honor. Upon accepting his Certificate of Appreciation, Oppenheimer addressed the mesa’s entire workforce (each of whom later received a sterling-silver pin stamped with a large A and a small BOMB, in recognition of his or her service):

“It is our hope,” Oppenheimer said, “that, in years to come, we may look at this scroll and all that it signifies, with pride. Today, that pride must be tempered with a profound concern. If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and of Hiroshima. The peoples of this world must unite or they will perish. This war, that has ravaged so much of the Earth, has written these words. The atomic bomb has spelled them out for all men to understand. Other men have spoken them, in other times, of other wars, of other weapons. They have not prevailed. There are some, misled by a false sense of human history, who hold that they will not prevail today. It is not for us to believe that. By our works, we are committed, committed to a united world, before this common peril, in law, and in humanity.”

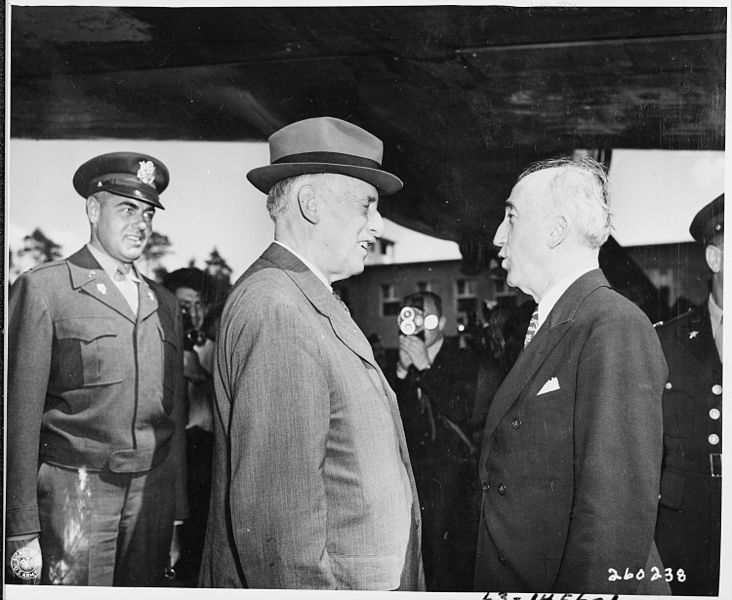

On October 25, 1945, Truman received Oppenheimer in the Oval Office; the physicist had requested the meeting in an effort to persuade the president to support international controls on nuclear weapons. Truman disarmed Oppenheimer by asking when the latter thought the Russians would develop a nuclear weapon; Oppenheimer replied that he did not know, to which Truman interjected: “Never!”

Sensing a lack of urgency in the US leader, and perhaps a little overwhelmed by this meeting, Oppenheimer confided, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” The remark infuriated Truman, who bluntly replied (as he later told David Lilienthal, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission), that “the blood is on my hands; let me worry about that,” and then smoothly ejected the physicist from his office and instructed Dean Acheson never to bring “that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

Oppenheimer meant that he wore the blood of future casualties of nuclear war, not the blood of the Japanese. The “cry-baby scientist,” as Truman later dismissed him cared not for the Japanese – who were “poor little people,” the collateral damage of a war they had brought on themselves; he wept for the Western victims of a future nuclear Armageddon. Oppenheimer’s remark alluded to his responsibility for the deaths of millions of individuals in some distant apocalypse which would be traced to Little Boy and Fat Man.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki served as terrible, necessary, examples of what the bomb might do; he did not think of them as avoidable tragedies in their own right. He quickly cast forward – as though he dared not look back – to a world in which, he dreamed, global controls on nuclear weapons would entrench a lasting peace. In later years, he alluded to a collective sense of regret for the general horror of war.

He spoke of the “numbing and indifference” that World War II had imbued in mankind; he warned that “we have made a very grave mistake” in contemplating the massive use of the weapon; and that, “in some sort of crude sense ... the physicists have known sin.” He did not define the nature of his “sin.” Oppenheimer’s mind was impervious to the probes of an ordinary conscience. He felt a terrible responsibility for what might happen; not for what he had helped to do.

His great speech of November 2, 1945 to the Association of Los Alamos Scientists was notable for what it did not say. The man who bore most responsibility for developing the weapon did not name Hiroshima or Nagasaki; they were already part of a fading past. He made one oblique reference, however, that suggested niggling regret: “There was a period immediately after the first use of the bomb when it seemed most natural that a clear statement of policy, and the initial steps of implementing it, should have been made; and it would be wrong for me not to admit that something may have been lost, and that there may be tragedy in that loss.”

He called for noble goals – the shared exchange of atomic knowledge, the creation of a world fraternity of nuclear scientists, and the abolition of nuclear weapons; he spoke of the “deep moral dependence” of mankind during the “peril and the hope” of the nuclear era; he cited Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. He charmed and pullulated, and a kind of statesman was born. These were, however, the impossible ideals of a very clever problem-solver, not a moral visionary.

Grand gestures could not change the fact that Oppenheimer had personally recommended a nuclear attack on a city of civilians, without warning. This happened; the rest was wistful dreams. He later insisted – perhaps it was unbearable to think otherwise – that the atomic bombs “cruelly, yet decisively ended the Second World War.”

Scandal and tragedy punctuated the rest of Oppenheimer’s life. The recipient of several job offers, from Harvard, Princeton and Columbia, Oppenheimer chose initially to return to Berkeley. He would serve in Washington as an adviser and contributor to the Acheson-Lilienthal Report on international atomic controls. His acme as chairman of the powerful General Advisory Committee to the US Atomic Energy Commission came tumbling down with the suspension of his security clearance in 1954: the inquiry dredged up his pre-war associations with communists, notably his late lover Jean Tatlock and his friend Haakon Chevalier, who claimed the scientist had been a member of a communist cell.

The witch hunt, of course, was a “travesty of justice,” and had more to do with Oppenheimer’s refusal to support the hydrogen bomb project than any serious truck with Reds. That Groves should be among those who refused to clear him would surely have embittered a lesser man; but Oppenheimer rode the inquiry with dignity and circumspection.

He retained his job as director of the Institute of Advanced Study, and was later rehabilitated and retired with a certain honor. He died on February 18, 1967. In 2023, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm voided the McCarthy-era revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance.

If Oppenheimer lacked the moral courage directly to recognize his role in the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the facts of the atomic bombs jolted other scientists, as if from a fitful sleep, to a keener awareness of a terrible new reality. Many lapsed into torments of self-accusation and spent much of their lives expiating their guilt.

Physicist Mark Oliphant, for example – who had played a critical role in persuading the US to build the bomb – “could hardly believe the early reports of the incineration of Hiroshima ... for he had not really come to grips with the possibility that a civilized and reputedly Christian nation was capable of such a deed.” His denial was hardly credible: what on Earth did he suppose he had been working on, if not a bomb that would, if the chance arose, be used? Unlike Oppenheimer, Oliphant ran the gauntlet of guilt and later damned himself: “During the war, I worked ... on nuclear weapons so I, too, am a war criminal.”

Leo Szilard and the Franck Committee imposed, to a lesser degree, a similar self-indictment. Their consciences were less burdened, as they had persisted with their protest weeks before the nuclear destruction of the two Japanese cities. Many of these dissident scientists, however, had been all too eager to drop the bomb on Germany – casting a shadow over the consistency of their moral position: Were they opposed to the nuclear destruction of all innocent civilians, or just non-German ones?

Many were Jews who had lost family members in the Nazi round-ups, and their personal loss clearly influenced their support for the destruction of Germany. At the time, however – 1941–44 – they were unaware precisely of what had become of their families and friends. The Soviets liberated the first Nazi death camp in July 1944. Many émigré scientists turned decidedly cool on the bomb when Japan loomed in the sights of the Target Committee; Szilard in particular had adopted “diametrically opposite positions” in relation to Germany and Japan.

James Conant, the chemist who drove the S-1 program, manifested a third expression of the scientists’ moral dilemma: pride and an utter lack of remorse were the hallmarks of his response to the atomic bombs. Conant disdained those scientists who “paraded their sense of guilt” about the bomb. The moral conflict over Hiroshima “hardly existed in my mind,” said the man who had led America’s mustard-gas research program during World War I and played a vital role in the development of the proto-napalm that was dropped on Japanese cities.

Conant understood the gravity of a nuclear arms race; his answer was to ratchet up America’s nuclear arsenal to force concessions from the Kremlin. Within weeks of Hiroshima, he advised the War Department to prepare for nuclear war. Fear of an atomic conflagration should not render the American public insensible or hysterical, he counselled – for that may lead them to reject the new weapon.

Fear must be managed, distilled, and drip-fed to the people, rather like a doctor treating a person with diabetes. “The physician, therefore,” Conant wrote, “had to frighten the patient sufficiently in order to make him obey the dietary rules; but if he frightened him too much, despondency might set in – hysteria, if you will – and the patient might overindulge in a mood of despair, with probably fatal consequences.”

Conant’s arms race had limits: he drew the line at the creation of the first hydrogen bomb, which he opposed in his capacity as a member of the General Advisory Committee on thermonuclear power. He saw in its hideous potential the capacity “to destroy far more than military objectives might ever justify” – surely, a self-deceiving view after the events of August 6 and 9.

He reconciled his opposition to the superbomb on the grounds that nations at peace had no moral case for building such a weapon. “Let us freely admit,” he said in 1943, with reference to general advances in the technology of weapons of mass destruction, “that the battlefield is no place to question the doctrine that the end justifies the means” – that is, in war, anything goes, mustard gas, napalm, etc. “But let us insist, and insist with all our power, that this same doctrine must be repudiated in times of peace.” In his old age, fretful over his role in the bomb, Conant conceded that it had been a “mistake” to destroy Nagasaki.

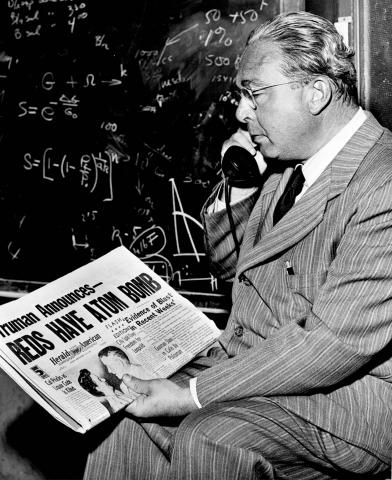

In Edward Teller, we encounter a fourth response: the utter rejection of any controls on nuclear arms. Teller was the apotheosis of the “warrior-scientist,” a man who gave his working life to the hydrogen bomb, and who saw in the megaton dawn over Eniwetok the harbinger of the American century. Teller, on whom Stanley Kubrick partly modeled the character of Dr. Strangelove, argued that America must equal or exceed the Soviet balance of terror – to assure the continuation of world peace. Negotiation, compromise, the preservation of the species, the ideal of a shared humanity: none had any traction on his argument that only by matching the Soviet arsenal could peace be assured.

The planet was doomed, Teller believed, unless America subscribed to the logic of mutually assured destruction, in which bigger and more devastating bombs were the sole currency. Peace would only prevail in a world in which each side possessed the power to annihilate the other. In this, he was prophetic.

The grim truth is that posterity has thus far judged him, and the exponents of MAD, partly correct, insofar as we have avoided a nuclear war through the assurance of mutual annihilation. That does not mean, of course, that it will not happen, and the dire uncertainty and immense expenditure of maintaining the balance of mutually assured death turned the minds of enlightened leaders to the policy of nuclear disarmament.

And the politicians? After the war, they stuck to their guns. Truman, Stimson, and Byrnes argued that the bomb alone had ended World War II and saved hundreds of thousands, if not a million, American lives. Stimson traveled a difficult road to this position. The Secretary of War had repeatedly bemoaned his countrymen’s indifference to the firebombing of Europe and Japan and the “appalling lack of conscience and compassion” the war had brought.

His colleagues on the Interim Committee on nuclear energy, formed in June 1945, were at least consistent: having approved the firebombing of civilians, how, then, could they oppose the nuclear bombing of them? The atomic bombs were a continuation of the existing strategy of civilian extermination to break the people’s “morale.”

If words alone shall be his judge, Stimson was consistent: he had objected to targeting civilians – in private talks with Truman – and maintained on May 16, 1945 that the “same rules of sparing the civilian population should be applied as far as possible to the use of any new (atomic) weapons.” His actions betrayed this apparent conviction. He raised no objection when the Interim Committee proposed the nuclear destruction of an urban area. In so doing, he was reduced to accepting the grotesque casuistry that “workers’ homes” represented a military target.

His fixation with the temples and shrines of Kyoto – as if they were mankind’s last link with a dying civilization – brought to a point all the frustrations of a man unable to reconcile conscience with action. Tens of thousands of civilians would die, regardless of whether the bomb fell on shrines in Kyoto or workers’ homes in Hiroshima.

Stimson erased this truth from his mind, whose elasticity would stretch to one last act in the story of the bomb. This eminent statesman who had done more than any high official to question (if not oppose) the bomb, would now serve as the official mouthpiece for the arguments deployed in favor of using it.

Stimson’s role was to “silence the chatterers” – the scientists, journalists, and clerics whose shrill denunciations of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had put the White House in the witness box. Their case gathered momentum in 1946: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, for example, published on May 1 the Franck Committee’s report opposing the bomb, which the influential radio broadcaster Raymond Swing gave national airplay.

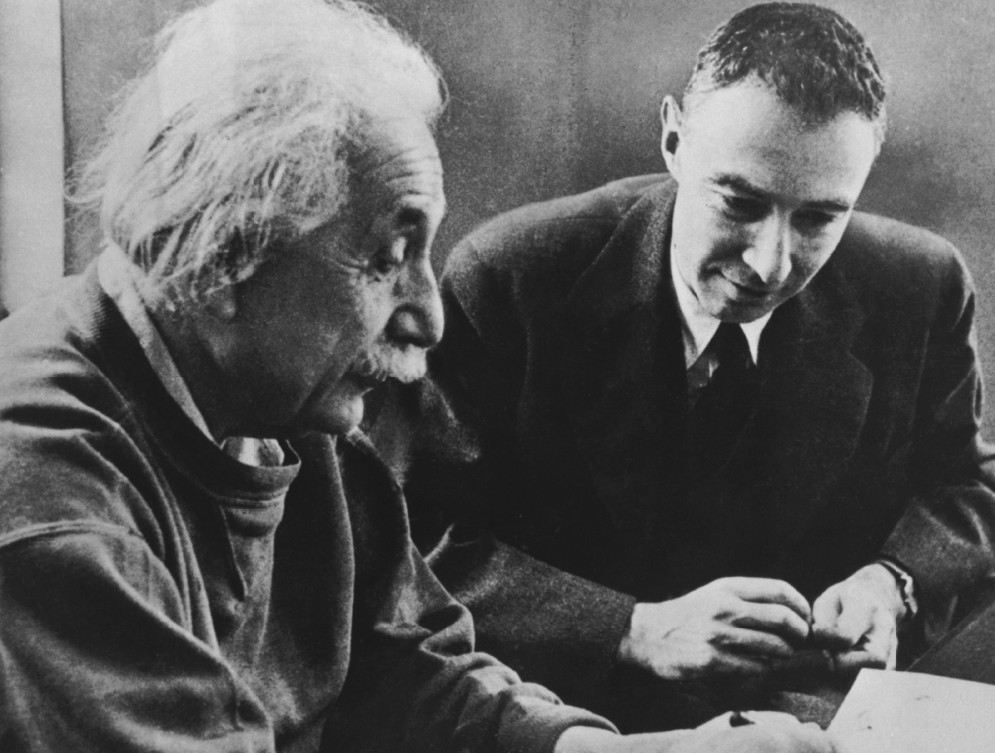

Albert Einstein, in a front-page article in the New York Times, “deplored” the use of the weapon. John Hersey’s article Hiroshima – which occupied an entire issue of The New Yorker (on August 31) – showed Americans what it meant to experience a nuclear attack through the lives of six survivors, and had a huge impact on perceptions of the nuclear weapons (notwithstanding the reporter Mary McCarthy’s demolition of Hersey’s article as a “human interest story” that treated the bomb as an earthquake or other natural disaster and failed to consider why it was used, who was responsible, and whether it had been necessary).

Prominent official voices joined the backlash. In 1945, Truman extended the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) to the Pacific, in order to record the effectiveness of the air war over Japan. Its findings, which appeared in July 1946, diametrically opposed Truman’s case for the bombs. The USSBS argued that the weapons were unnecessary and that Japan had been effectively defeated long before their use.

That much the military commanders already knew. But the study went further, speculating that Japan would have surrendered “certainly prior to December 1, 1945, and in all probability, prior to November 1, 1945 ... even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” This seems unlikely. Tokyo refused to yield, and the Russian invasion played a decisive role in Japan’s surrender. The USSBS’s conclusions have been heavily criticized. At the time, however, the report certainly added to the growing unease over nuclear weapons.

Washington insiders, chiefly Conant, were concerned about the cumulative effect of these voices, and he proposed a reply. The result was a long article, in Stimson’s name, sourced to a memorandum from his assistant, Harvey Bundy, and written largely by Bundy’s precociously clever son, McGeorge. Groves, Conant, and several senior officials edited the draft.

The article first appeared in the February 1947 issue of Harper’s Magazine, then reappeared in major newspapers and magazines, and was aired on mainstream radio. It purported to be a straight statement of the facts, and quickly gained legitimacy as the official case for the weapon.

The Harper’s article reinforced in the American mind the idea that the atomic bomb saved hundreds of thousands of American lives by preventing an invasion of Japan. The article’s central plank was that America had had no choice. There was no other way to force the Japanese to surrender than to drop atomic weapons on them. By this argument, the atomic bombings were not only a patriotic duty, but also a moral expedient:

“In the light of the alternatives which, upon a fair estimate, were open to us, I believe that no man, in our position and subject to our responsibilities, holding in his hands a weapon of such possibilities for accomplishing this purpose and saving those lives, could have failed to use it and afterwards looked his countrymen in the face.

The decision to use the atomic bomb brought death to over a hundred thousand Japanese. No explanation can change that fact, and I do not wish to gloss over it. But this deliberate, premeditated destruction was our least-abhorrent choice. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki put an end to the Japanese war. It stopped the fire raids and the strangling blockade; it ended the ghastly specter of the clash of great land armies. “

Editors and the public warmly approved: here, they felt, was an honest justification for this horrific weapon; the A-bomb did good, in the end. The Harper’s article put the American mind at ease, slipped into national folklore, and the Stimsonian spell appeared to tranquilize the nation’s critical faculties on the subject.

Only the Washington Post made a serious attempt at a critique. It trenchantly argued that, contrary to Stimson’s claim, clear evidence was available of Japan’s terminal weakness before the bombs, and that his “apologia” would “not altogether remove the feeling that the use of the bomb put upon us the mark of Cain.”

The Harper’s article was profoundly flawed. Stimson had not intended to deceive the American public, but the omissions and selective use of facts deployed in his name had that effect. The essay made no mention of the long debate over the role of the emperor and Japan’s last (and only persuasive) offer to surrender on condition that Hirohito be preserved (a condition that Washington, in the end, accepted).

Nor did it mention the opposition of senior officials to bombing a city without warning – a target that only the most wilfully self-deceived could construe as “military;” or the Soviet Union’s role in the timing of the bomb; or the USSBS’s (contested) claim that a defeated Japan would have surrendered without the bomb or an American invasion.

Most erroneously, it argued that a land invasion of Japan and the atomic weapons were mutually exclusive – a case of either-or. This flawed nexus ignored the fact that Truman and his senior military advisers had all but abandoned the land invasion by early July 1945, irrespective of whether the Trinity test on July 16 had bathed Alamogordo in neutrons.

Basic errors of fact compounded these sins of omission. The article was plain wrong, for example, to claim that the “direct military use” of the bomb had destroyed the “active working parts of the Japanese war effort.” Nobody on the Target Committee pretended that “working men’s homes” were military targets whose destruction would seriously hamper the enemy’s fighting ability. In any case, more than 90 per cent of Hiroshima’s war-related factories were on the city’s periphery. On Conant’s nod, the committee had clearly recommended that the bomb be dropped on the heart of a city – that is, on civilians. The priority was not the destruction of “workers’ homes” (though their presence served a useful public relations role); it was to shock Japan into submission by annihilating a city.

As to Stimson’s claim that America used the bomb reluctantly – “our least abhorrent choice” – suggesting that Washington and the Pentagon had wrestled painfully with alternatives, the facts demonstrate precisely the opposite. Everyone involved expected, indeed hoped, to use the bomb as soon as possible, and gave no serious consideration to any other course of action. The Target and Interim Committees swiftly dispensed with alternatives – for example, a warning, a demonstration, or attacking a genuine military target.

Indeed, Secretary of State Byrnes rejected these options over lunch at the Pentagon – arguing that a warning imperiled the lives of Allied POWs whom the Japanese would move to the target area (the US Air Force had shown no such restraint in the conventional air war, which daily endangered POWs).

As well as this, he argued, a demonstration might be a dud (unlikely, given Trinity’s success, and the fact that Manhattan scientists saw no need even to test the gun-type uranium bomb used on Hiroshima); that they had only two bombs (untrue – at least three were prepared for August, and several were in line for September through November); and that there were no military targets big enough to contain the bomb. In fact, Truk Naval Base was considered and rejected; no other military target was seriously examined; only Kokura, a city containing a large arsenal, came close to that description, and the attempt to bomb it was abandoned due to the weather.

The nuclear attacks were an active choice, a desirable outcome, not a regrettable or painful last resort, as Stimson insisted. The administration never seriously considered any alternative; its members focused on how, not whether, to use atomic weapons.

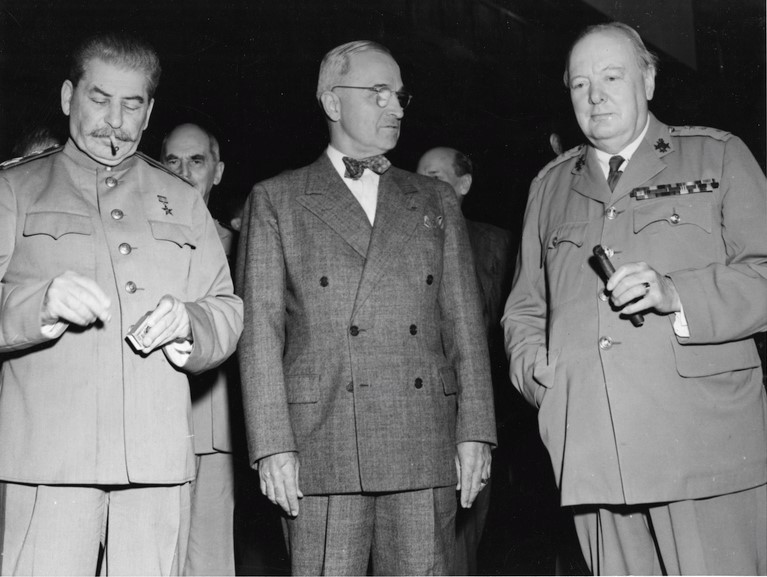

Every high office-holder believed the bomb would be dropped if Trinity proved successful. “I never had any doubt it should be used,” Truman said on many occasions. “The decision,” wrote Churchill later, “whether or not to use the atomic bomb to compel the surrender of Japan was never an issue.” Groves dismissed Truman’s role as inconsequential. “Truman’s decision,” the general wrote, “was one of non-interference – basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.”

In this context, a complete Japanese surrender at an awkward time – that is, after Trinity’s success and before the bombs arrived on Tinian – would have frustrated any hope of using the weapons. This is not to impute sinister motives to any man, whose heart and mind we may never truly know, but simply to assert that Washington and the Pentagon were absolutely determined to use the two atomic bombs. “American leaders did not cast policy in order to avoid using the atomic weapons,” in the historian Barton Bernstein’s view. The phrase “our least abhorrent choice” grossly misrepresents a gung-ho, diabolically zealous, enterprise.

Stimson’s least persuasive claims were that the atomic bombs ended the war and prevented up to a million American casualties. While the bombs obviously contributed to Japan’s general sense of defeat, not a shred of evidence supports the contention that the Japanese leadership surrendered in direct response to the atomic bombs. On the contrary, Tokyo’s hardline militarists shrugged as the two irradiated cities were added to the tally of the 66 already destroyed, and they overrode the protests of the moderates.

The Japanese hardliners barely acknowledged the news of Nagasaki’s destruction. Nor would a nuclear-battered Japan consider modifying its terms of “conditional surrender:” the leaders clung stubbornly to that central condition – the retention of the emperor – to the bitter end. In fact, state propaganda immediately after Hiroshima and Nagasaki girded the nation for a continuing war – against a nuclear-armed America.

A regime that cared so little for its people, except insofar as they served as cannon fodder in a last miserable act of national seppuku; a nation so fearful of the Soviet Union that it sent message after message imploring their intervention in the dying months of war; a people so steadfast in their refusal to yield that they actually prepared to defend their cities against further atomic bombs – this was not a country easily shocked into submission by the sight of a mushroom cloud in the sky (and it is worth remembering that, the day after, Tokyo had no film or photographs of the bomb, but only US pamphlets and military reports claiming it had been used).

A greater threat than nuclear weapons – in Tokyo’s eyes – drove Japan finally to accept the surrender: the regime’s suffocating fear of Russia. The Soviet invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria, of the Sakhalin and Kuril islands and northern Korea on August 8 crushed the Kwantung Army’s frontline units within days and sent a crippling loss of confidence across Tokyo. The Japanese warlords despaired. Their erstwhile “neutral” partner had turned into their worst nightmare. The invasion invoked the specter of a communist Japan, no less.

Russia matched iron with iron, battalion with battalion. This was a war that Tokyo’s “samurai” leaders understood, a clash they respected – in stark contrast to America’s incendiary and atomic raids, which they saw as cowardly attacks on defenseless civilians.

Americans are not alone in seeing the past through their national prism. Their nation’s pervasive power, however, enables them to project a decidedly American impression of what happened – or should have happened – onto the rest of the world. Photos of the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima impressed most Americans, who could readily imagine the pulverization of St. Louis or Dallas or Chicago.

How on Earth would the little yellow people endure such a fate? Other realities, however, prevailed in Tokyo and Moscow – a ground war of immense military dimensions and far-reaching political implications, which had a more exacting influence on Tokyo’s decision to surrender than the death of two more cities.

What of Truman? The president knew the script well. On August 6, he told Eben Ayers, his assistant press secretary, that military advisers had warned that a million men might be needed to invade Japan, with casualties of 25 per cent. Truman estimated that, if Hiroshima’s population were 60,000, then “it was far better to kill 60,000 Japanese than to have 250,000 Americans killed … I therefore ordered the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

In fact, he had approved a decision that had been made for him in the extraordinary confluence of American industrial wealth, European scientific brilliance, Japanese war crimes, Russian imperialism, the incendiary campaigns over Germany and Japan, and the acute geopolitical pressures of the last year of the war, which met in the minds of Churchill and Roosevelt at Hyde Park. Only a character of unearthly will, vast authority, and transcendent moral vision could have resisted the fatal momentum of the atomic project. However great a president, Harry Truman was not that character.

The president never lost any sleep over “his” decision, he often claimed; he would have done it again, he said on several occasions. He told a Mrs. Klein, years after the war, that the bomb saved a quarter of a million American and Japanese boys. As a result, “I never worried about the dropping of the bomb. It was just a means to end the war.”

He told a 1958 CBS See It Now TV report that he had “no qualms” about ordering the use of the atomic weapon on Japan, which prompted a letter of protest from the Hiroshima City Council, in reply to which Truman attempted to justify the use of the bomb as revenge for Pearl Harbor.

The council responded: “Do you consider it a humane act to try to justify the outrageous murder of two hundred thousand civilians of Hiroshima, men and women, young and old, as a countermeasure for the surprise attack (on Pearl Harbor)?” The Nagasaki Municipal Assembly also weighed in: “We deeply regret the war crimes committed by our nation during the last world war ... Nevertheless, we cannot remain silent in the face of your persistent attempt to justify the atomic raids.”

Again on August 5, 1963, in a letter to Irv Kupcinet of the Chicago-Sun Times, Truman claimed that the bomb saved 125,000 American and 125,000 Japanese “youngsters” and avenged Pearl Harbor. Oddly, in the same letter, he doubled the number of lives he reckoned he’d saved: “I knew what I was doing when I stopped the war that would have killed a half a million youngsters on both sides if those bombs had not been dropped. I have no regrets and, under the same circumstances, I would do it again.”

He protested too much, it seems. He later told the Enola Gay’s pilot Paul Tibbets not to lose any sleep over the mission. “It was my decision. You had no choice.” Selflessly determined to shoulder the burden alone, Truman moved to silence the worm of conscience in others.

The simple fact is that Truman never presented the bomb as an alternative to invasion until after the war. He had always resisted the invasion of Japan, regardless of whether the bomb worked. He expected that the naval blockade, the air war and – at least, until mid-July – the Russians would together finish the job. George Marshall, Henry Stimson, Admiral Leahy, General Eisenhower, and Admiral Halsey all came to believe this, to a greater or lesser extent.

The president was too smart a politician – with a genuine desire to protect American lives – to risk political suicide through the loss of so many young men against a regime that everyone in power in Washington knew was, for all practical purposes, defeated. In this context, the bomb was not a substitute for an invasion, for the simple reason that Truman had no intention of approving one. He could not say this after the war because that would have emasculated his claim that the bomb saved up to a million lives.

The magic number is hard to source. At various times, from 1947 on, Truman, Stimson, and Byrnes argued that the bomb saved a quarter of a million, a million, and millions of lives. How they arrived at these figures is a question of deep and continuing controversy. On one occasion, Jimmy Byrnes contended that the weapon rescued “some millions (of Japanese people) who would have perished (under) incendiary bombs (used) against a people whose air force had been destroyed.”

By ending the war, Byrnes implied, the bomb also ended the firebombing missions that were steadily exterminating the Japanese people. Only a peculiarly gymnastic political mind could have managed this somersault of present expediency over past reality: the bomb was not built to deliver the Japanese people from the wrath of Curtis LeMay.

Years after the war, Truman sourced his casualty estimates to General Marshall who, Truman said, had privately warned him that invading Japan would cost “as much as a million” dead and wounded “on the American side alone” (despite the fact that Marshall had predicted 31,000 casualties at the meeting on June 18, 1945).

Truman appears to have drawn on several other sources – not least former President Herbert Hoover’s warning in a memo on May 15, 1945 that an invasion would cost between “500,000 and 1,000,000” American fatalities – a death rate of such astonishing scale as to discredit this analysis, regardless of Hoover’s access to “intelligence briefings.”

US military experts – notably, General George Lincoln – derided Hoover’s calculation as deserving “little consideration;” Hoover’s upper limit in fact implied total casualties (that is, including wounded and missing) of between three and five million. That the comparatively weak and dispirited Japanese might kill or wound virtually every American soldier several times over was ludicrous: the US commanded the air over Japan and ringed the islands in steel. Its armies were well trained and equipped, and the enemy was in an abject state.

Nonetheless, the American press and public fixed on the magic number – 1,000,000 American dead – as a monument to the justification of the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is worth restating that Truman and the Joint Chiefs approved the planning of an invasion of Kyushu – not its execution – at the June 18 meeting, on the modest assumption of 31,000 battle casualties (dead, wounded, and missing) in the opening phase of the invasion.

These numbers, no less dreadful to the family of one of those killed, hardly made invasion desirable or advisable, of course – especially if a credible alternative (blockade, bombardment, Russian intervention) would force the surrender. The point is that Americans – from ordinary citizens to serious thinkers – continue to justify the bomb with a blizzard of unreliable casualty estimates for an invasion that Truman had not approved and was desperate to avoid. America’s collective conscience – unable, perhaps, to bear any other interpretation – seems to have fixed on this version of the past.

There were other ways of saving American lives – if we accept this as Washington’s most urgent imperative – each admittedly fraught with risks, but surely worth consideration. These were by clarifying the terms of “unconditional surrender” and the status of Hirohito, whose continuation in a symbolic role every sentient Washington official knew would be vital in managing post-war Japan; by offering to test the bomb before the eyes of the United Nations – with Japanese observers in attendance – as the Franck Committee had proposed, which, although fraught with practical problems, had the advantage of demonstrating America’s civilized restraint; or seriously encouraging Russia to enter the war and retaining Moscow’s signature on the Potsdam Declaration (a course which, after Trinity, was the least appealing option for Truman and Byrnes).

Truman chose none of these alternatives or any variations of them. With Byrnes at his ear, he rejected the counsel of the former ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew and Henry Stimson, who recommended the gift of the emperor’s immunity as the quickest way to end the war. He did not actively solicit Russian help. If he went to Potsdam, as he said, to get the Russians into the Pacific, he left Potsdam determined to keep them out. “Truman,” observed the historian Barton Bernstein, “did nothing substantive at Potsdam to encourage Soviet intervention and much to delay or prevent it.” Everything changed with the Trinity test in the Jornado del Muerto (the Journey of Death, as the Spanish conquistadors named it in the 1500s) desert in New Mexico, of course. The first nuclear-armed president believed he had no further need of his erstwhile ally.

These actions may not have resulted in Japan’s surrender, of course. The point is that, if ending the war and saving lives were Truman’s chief aim, why did he not explore these alternatives? The historian Gar Alperovitz answered that “saving lives was not the very highest priority” – ascribing an unmerited callousness to the American leadership. More accurately, the United States sought to end the war on its own terms, and in accordance with the wishes of its people, who would never forgive Japan for Pearl Harbor.

The bomb, Truman believed, handed him that opportunity. He felt that it removed the need to engage the Russians or appease the Japanese. America would win the war on its terms – without Russian help – and proudly.

After the war, Truman tried to amend the record to project this noble sentiment. The Japanese were given no warning of the first bomb. In 1959, Truman emphatically denied this to an astonished Richard Hewlett, author of the official history of the US Atomic Energy Commission.

“Certainly,” Truman said, “the Potsdam Declaration did not contain such a warning, but the Japanese had been warned through secret diplomatic channels by way of both Switzerland and Sweden ... This warning told the Japanese that they would be attacked by a new and terrible weapon unless they would surrender.” Asked whether he had copies of the cables, Truman replied that they could be found in the files of the State Department or CIA. No record of any such warning has been found.

A less clear-cut issue divided Truman and Byrnes after the war – and has vexed historians ever since: whether the bomb was used as an emphatic expression of American power to deter Russian aggression in Europe and Asia. Absolutely not, Truman told Richard Hewlett; the president had always claimed that his primary motive at Potsdam was to get the Russians into the war. Byrnes, on the other hand, believed the bombs had a definite role in “managing” the Soviet Union, and told US News in the 1960s that they were dropped to end the war “before Russia got in.” In a later interview with Fred Freed of NBC, Byrnes undermined Truman’s public position: “Neither the president nor I were anxious to have (the Russians) enter the war after we had learned of the successful test.”

No documentary evidence exists to support the blackest reading of Byrnes’ role – that he engineered Japan’s refusal to surrender until the bombs were ready. It is intriguing to speculate, nonetheless, whether the Japanese would have surrendered had they received the Byrnes note before the atomic bombs fell.

Remember that Tokyo’s “peace faction” had repeatedly requested the emperor’s continuation on the throne as the sole precondition for surrender. After the bombs, they doggedly stuck to this condition; Hiroshima and Nagasaki made little dent in their resolve on this issue. They surrendered only after the Russians invaded and after the Byrnes note effectively met Tokyo’s condition. In this light, it seems likely that Japan, in receipt of the Byrnes note, and in the grip of the Russian onslaught, would have surrendered without the use of atomic bombs.

In a similar spirit of hypothetical inquiry, what might have happened had America not used the atomic bombs? One probable scenario is this: Within weeks, Russia would have crushed Manchuria, and Japan – crippled by the naval blockade, subjected to constant conventional aerial attack, and fearful of the communist advance – would have surrendered to the more acceptable enemy, America. No US invasion would have been necessary. The total casualties, Allied and Japanese, of this scenario are unknowable.

The chiefs of the armed forces took a different line on the bomb. The bomb dismayed many of America’s most senior soldiers. There was something deeply abhorrent to the traditional commander’s mind about the air war on Japanese civilians. Deliberate, indiscriminate slaughter of noncombatants – unless a woman or child with a bamboo spear may be classed as a combatant – did not figure in their conception of warfare.

The new world order reflected this view: of what use were the Hague and Geneva Conventions if not to protect the innocent, preserve the lives of prisoners, and limit unnecessary cruelty? In defying them, Japan and Germany had waged a bestial campaign against the very essence of what distinguishes the species as human. Surely, America, the self-appointed standard-bearer of God-fearing morality, would not follow them?

The use of nuclear weapons was unconscionable and/or militarily unnecessary – so argued Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur, and Admirals Halsey, King and Leahy. They each condemned and opposed, with varying degrees of emphasis, the nuclear attacks – on strategic and/or moral grounds. But they only did so publicly after the bombs fell, which diminished their arguments – a case of wanting to look virtuous after the event.

Pride also played a part in their objections to the bomb: their own forces – sea, conventional air, and land troops – would have defeated Japan without atomic weapons, they contended, to a greater or lesser degree. They believed the war would have ended anyway, by blockade, bombardment and/or Russian help (only MacArthur, in the last weeks, held a candle for the invasion).

Leahy was the most emphatic opponent of the bomb: for him, dropping it on Japan was an act of inhumanity unworthy of a Christian country. “It is my opinion,” he wrote in his memoirs, “that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender (on their terms, Leahy omits to say) ... In being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages ... Wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.” Halsey, the much-feared commander of the 3rd Fleet, publicly declared on September 9 that the “first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment ... It was a mistake ever to drop it.” He dismissed the weapon as a “toy” that the scientists “wanted to try out.”

MacArthur, perhaps the last of the gentlemen soldiers, was implacably opposed; his aide, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers, described America’s strategic air offensive – in its incendiary and atomic forms – as “one of the most ruthless and barbaric killings of noncombatants in all history.” Army Air Forces Generals Hap Arnold and LeMay were arrogantly dismissive of the new weapon, which merely continued, they believed, what they had started. For them, incendiaries and conventional explosives would have eventually forced Japan to surrender, a campaign LeMay proudly portrayed in terms of the body-count scorecard that he would later apply in Vietnam. “We scorched and boiled and baked to death more people in Tokyo on that night of March 9-10 than went up in vapor at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

General Eisenhower was adamantly opposed, after the event. He famously stated in his post-war memoirs that “in (July) 1945” – he was then Supreme Allied Commander in Europe –

“Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan ... During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression, and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly, because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of 'face.'"

In a Newsweek interview in 1963, the former president again alluded to what he had told Stimson, that “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

Japan’s smarter military commanders conceded this. They fought on in the hope of extracting conditions at the surrender. Japan’s most notorious general, Tomoyuki Yamashita, the “Tiger of Malaya”– a thick-set, bullet-headed giant of a man – summed up this attitude at the highest level during an interview in his prison cell in Manila in March 1946: “Our cause was lost even before you had recourse to atomic bombs and long-range bombers. We were fatally handicapped by lack of ... material resources.”

The American press helped to cement the myth that Japan surrendered in direct response to the nuclear attacks. The media reached this consensus after the war. In the months before the surrender, reporters sang a very different tune: then, newspapers and radio consistently portrayed Japan as starving, vanquished, reduced to sending out desperate peace-feelers, and so on. The contrast between the two Japans is startling and suggests an indoctrinated or confused press.

Which was the true Japan – the pathetic, hungry, defeated adversary that the press portrayed during the last months of the war, or the resilient, still-threatening nation whose surrender would require a land invasion or nuclear holocaust (or both)?

Neither portrayal was entirely accurate, but the former was closer to the truth. That’s not to say that the US media all bought the government’s post-war line. The Washington Post was a constant thorn in Truman’s side. And, intriguingly, the most strident critique of the newly minted “orthodox” view – that the atomic bomb ended the war and saved hundreds of thousands of lives – came from the right-wing press, in magazines such as The Freeman, National Review, and Human Events.

Truman’s refusal to modify the terms of “unconditional surrender,” observed Forrest Davis in The Freeman, came “little short of being a high crime and one that may return unmercifully to plague us.” These days, few agree with The Freeman: from US tabloids to Pulitzer prize-winning historians, the consensus is that the atomic bombs alone won the war and were our least abhorrent choice.

The stifling debate between those who claim that the bombs were dropped as a warning to Russia, the first blow of the Cold War, or to avoid a land invasion and save a million US lives, hardly helps our understanding of the complex reality of what actually happened in 1945. In its extreme form, each side presents a simplistic, partisan reading of the past, which superimposes a story that best reflects the beliefs of the authors, but little serves the pursuit of truth.

Indeed, the very terms “revisionism” and “orthodoxy” seem interchangeable, depending on the context, timing, and characters involved. Truman, for example, expressed what has become the orthodox view of the bomb after the war. His feelings were more complex before the armistice – in flux, amenable and, under Jimmy Byrnes’ influence, shaded with “revisionist” tendencies. For his part, Byrnes sounded robustly “revisionist” in his view of the bomb’s role in managing or subduing the Soviets. And Stimson’s “orthodoxy” was not fully formed until he put his name to an article in 1947. Minds and moods change for all kinds of reasons. To ascribe a single, static motive to the behavior of an individual or government little helps us to understand the complex interplay of relationships, thoughts, and feelings that drive human history.

The most that may be said in defense of the bombing of Hiroshima – in strictly military and political terms – is that it bounced the Russians into the war a week or so earlier than Moscow planned. Whether that justified the destruction of two cities is a different question. There appears to be no justification – in military or political terms – for Nagasaki. The two atomic strikes did, however, furnish Tokyo’s leaders with a face-saving expedient, to surrender to the more acceptable enemy. Far better to capitulate to a nuclear-armed, democratic America than to a vengeful, communist Russia.

Perversely, the bombs offered the Japanese leadership an unintended propaganda tool: it let them present the surrender as the act of a martyred nation, forced to yield, as Hirohito said, to a “new and most cruel bomb ... taking the toll of many innocent lives.” This characterization cruelly overshadowed the just claims of the victims of Japanese war crimes and was utterly false. Tokyo did not surrender to protect the Japanese people from the weapon; the leadership had shown not the slightest duty of care towards these “innocent lives.”

For the Japanese leaders, the bombs served another purpose, unwelcome in Washington: Tokyo was able to surrender without conceding defeat on the battlefield, where it mattered most to the “samurai” mind. In this sense, the imperial forces were able to capitulate with their military honor intact. Little Boy and Fat Man saved face for a people for whom that meant more than saving their lives.

In 1945, America occupied and started to rebuild the smoking disgrace of Japan – and turned its shoulder to the nuclear winter. The splitting of the atom, to paraphrase Albert Einstein, changed everything, except “the way men think.” Truman later expressed a similar spirit: “The human animal and his emotions change not much from age to age. He must change now, or he faces absolute and complete destruction, and maybe the insect age or an atmosphere-less planet will succeed him.” It reflected his new understanding of the bomb, not as a weapon of war, but as a clear and present danger to humankind.

I am less interested in finding villains than in understanding the bloody acts to which German and Japanese aggression had impelled the Allies to resort. Those acts were unconscionable and unworthy of the civilized world.

But, even if we accept Truman’s later defense of his decision – and no doubt, he sincerely wished to end the war as soon as possible and save as many lives as he could – the question is whether good intentions alone justify the flouting of war conventions and the massacre of ordinary people.

The bomb gave America’s tooth-for-a-tooth sensibility the power to scatter a billion molars. The United States used it, without warning, in an attempt to extract “unconditional surrender” from a defeated foe, to “manage” Russian aggression in Europe and Asia, and avenge Pearl Harbor, as Truman and Byrnes had made clear.

The bomb achieved none of those goals (unless two destroyed cities is accepted as proportionate punishment for Pearl Harbor): Tokyo surrendered with its sole condition more or less intact, and Russia continued to stomp and snort and foment “communist” revolution around the world – and would soon rush to join the nuclear arms race.

Taken together, or alone, the reasons offered in defense of the bomb do not justify the massacre of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians. We debase ourselves, and the history of civilization, if we accept that Japanese atrocities warranted American atrocities in reply.