After three of his plane's engines flamed out, Capt. John Murray was forced to land at night during a ferocious storm in the middle of the ocean.

-

November/December 2021

Volume66Issue7

Editor’s Note: One of the most dramatic books we’ve read recently is Eric Lindner’s tale of the crash of a Lockheed Constellation into the North Atlantic. We asked the author to give us an overview of the incredible story, which he had pieced together from interviews with survivors and information in files long hidden because of Cold War politics. More dramatic details can be read in Lindner’s Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger Flight 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival (Lyons Press). The extraordinary pilot, Capt. John Murray, was the author’s late father-in-law.

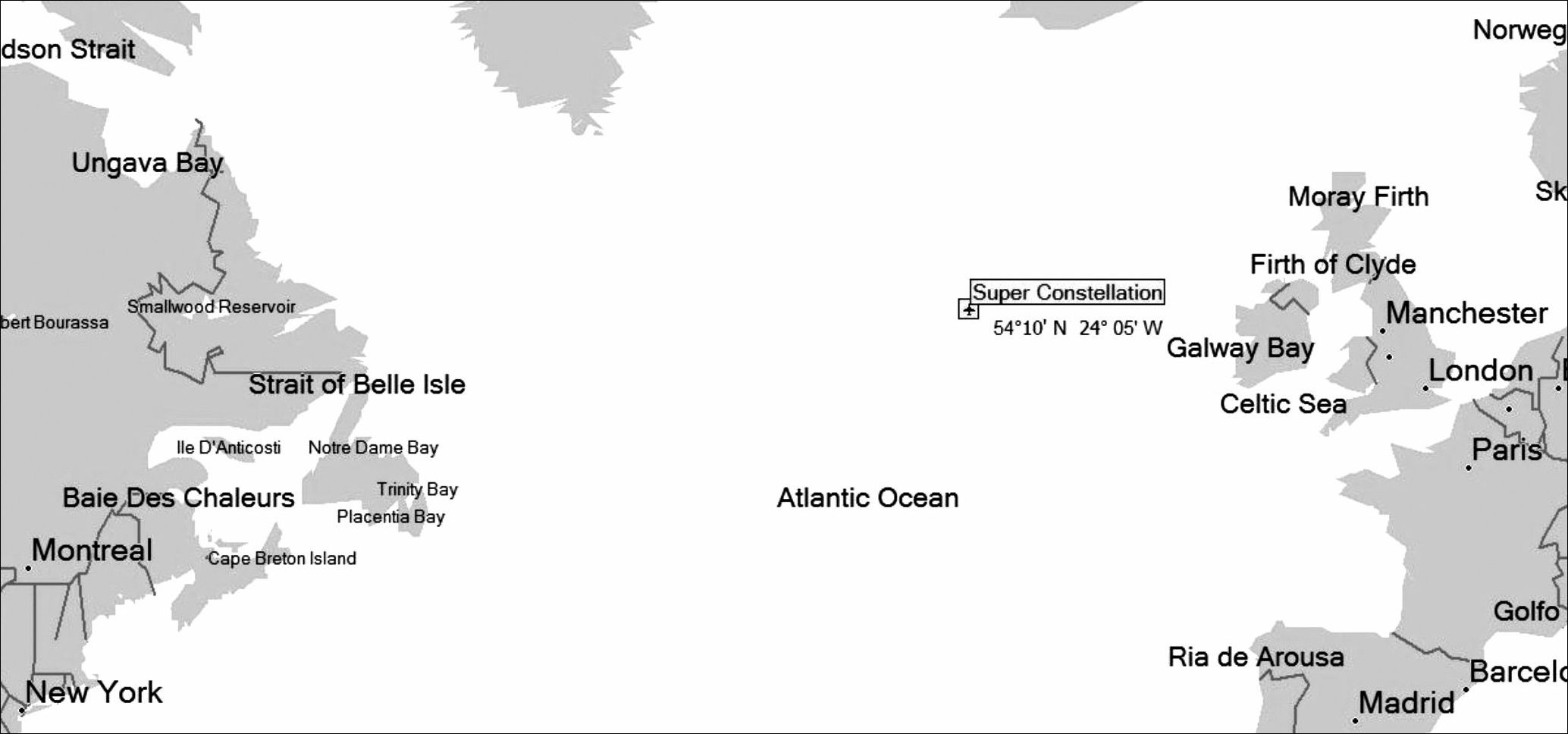

On a moonless night in September 1962, during a routine flight to Germany, three of the four engines of Flying Tiger flight 923 burst into flames, one after another. John Murray, the pilot of the stricken Constellation, would not have long before his plane with 76 souls on board crashed into 20-foot waves at 120 mph, at night in the middle of a raging North Atlantic storm somewhere nearly 600 miles west of the Irish coast.

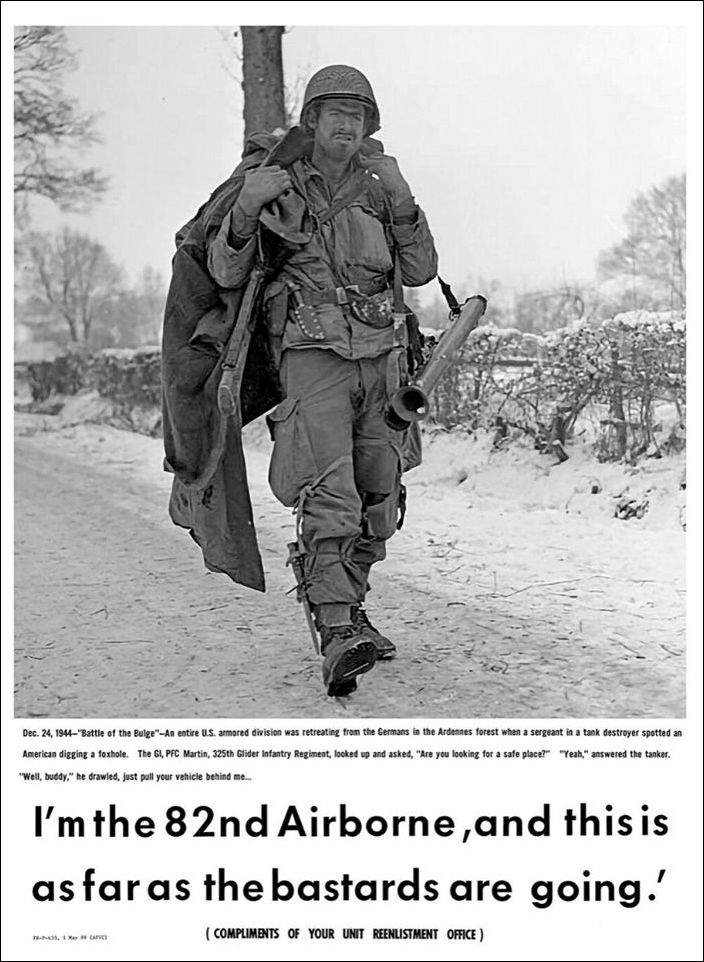

As the four flight attendants donned life vests, collected sharp objects, and explained how to brace for the ferocious impact, 68 passengers clung to their seats. There were elementary schoolchildren from Hawaii, a teenage newlywed from Germany, a disabled Normandy vet from Cape Cod, an immigrant from Mexico, and 30 recent graduates of the 82nd Airborne’s Jump School. They all expected to die.

Murray radioed out “Mayday” as he attempted to fly through gale-force winds down into the rough water, hoping the plane didn’t break apart when it hit the sea. But only a handful of ships could pick up the distress call so far from land.

Murray was a pilot for the Flying Tiger Line, formed by veterans of the vaunted Flying Tigers, a volunteer outfit of Americans that had earned its reputation during World War II helping the Chinese Air Force. The American military brass had rejected their innovative strategies of flying, but China hadn’t. When the Japanese attacked Burma, Thailand and Singapore with large sorties of bombers and fighters a few days after Pearl Harbor, it was their turn to be shocked as a few dozen Tigers downed 23 enemy aircraft without losing a plane. Forty-five Japanese planes attacked three days later: the outnumbered Tigers shot down 10 – again without a loss. The scoreboard that month in Burma: America 51, Japan 1.

The Tigers didn’t have superior aircraft, just superior pilots. Many historians say they were without peer. When the War Department tried to wrest control of the Tigers from the Chinese, they disbanded. But after the war, some of the Burma veterans formed a commercial airline. Flying Tiger Line’s first sortie flew grapes from California to New Jersey. John Murray was hired in 1950.

Singular Circumstances, Singular Man

By 1962 America was embroiled in another all-encompassing war that stretched from Berlin to Beijing. The Soviets had displaced the Nazis and China was no longer a friend but a foe. Again the (reconstituted) Tigers played a key, largely forgotten role. From their headquarters in Burbank’s Lockheed Air Terminal, they flew soldiers into war zones, and refugees out. Tiger mechanics built most of the permafrost Dew Line that played a vital role in the early warning system against nuclear attack. And many a lonely Marine said, “No one brings in mail like those Tiger birds.”

Come fall, the world was wondering not so much if but when the Cold War would get hot. In recent years, Communist China had helped North Korea nearly push the South Korean and American forces into the sea. The USSR had exploded history’s most powerful hydrogen bomb, crushed the Hungarian Uprising, downed the supposedly unreachable Lockheed U2 spy plane and paraded its pilot on the world’s stage as the poster child of American inferiority, helped install Fidel Castro and repulse the CIA-led Bay of Pigs invasion, and caught the CIA napping by erecting the infamous Berlin Wall almost overnight. A result was 30 paratroopers boarding Tiger 923 at McGuire Air Force Base at 11:09 a.m., September 23rd.

While on layover at Gander Airport, captain Murray’s flight engineer assured him that his Super Constellation (“Connie”) was running like a top, while a Canadian meteorologist said he was in for a smooth 15 hours to Frankfurt. In the annals of aviation history, few prognostications have been so wrong.

Tiger 923’s first problem arose on the runway at 5:10 p.m.: the main cabin door wouldn’t shut. Shortly after take-off, winds gusting to 65 mph (just shy of a Category I hurricane) and hail battering the hull required a steep, sudden climb from the planned 13,000-foot altitude, to 21,000.

At 8:07 p.m., a thousand miles from Ireland and four above the raging Atlantic, the inboard right-side engine burst into flames. A jolt of terror shot through the cigarette-smoke-filled passenger cabin, occupied by the paratroopers who’d graduated Jump School just five days prior; six couples on vacation; a Mexican immigrant whose father didn’t know his son had entered the U.S., let alone was in its Army or en route to its base in Germany; a Hawaiian mother with her two young daughters; and 22 other active military, vets, or dependents.

Murray was calm. He’d experienced more fires than he could remember, twice lost two engines over the Atlantic, twice crashed in Detroit. Egyptian anti-aircraft had riddled his fuselage when he helped a handful of Holocaust survivors create an air force out of some old Nazi plane parts in Israel in 1947, and he’d faced MIGs on his tail in the Berlin Corridor. Rated on seaplanes and on amphibian planes that operate on land or water, he wasn’t intimidated by the Orwellian prospect of “landing” on water. Unless of course it was at night during a gale.

Lastly, Murray knew Connies – the famous three-tail-finned Constellations – like the back of his hand: 85 percent of his flying over the preceding four years had been at the helm of his favorite plane.

Still, it wasn’t supposed to be this way. The 44-year old father of five and passionate sailor felt his adventurous days were over. He wanted to grow Christmas trees and set sail from his backyard on Long Island's Oyster Bay.

Murray knew he needed not just to suppress the fire but keep it from spreading to the No. 4 engine, draw up contingency plans to divert to an airport much closer than Frankfurt, keep the passengers from panicking while drilling them for a possible ditching, and alert air traffic control of his situation. He was assisted in the flight deck by first officer Bob Parker, flight engineer Jim Garrett, and navigator Sam “Hard Luck” Nicholson, so called because of the way Danger seemed to stalk him wherever he went; chief stewardess Betty Sims, Carol Gould, Ruth Mudd and Jackie Brotman comprised the cabin crew.

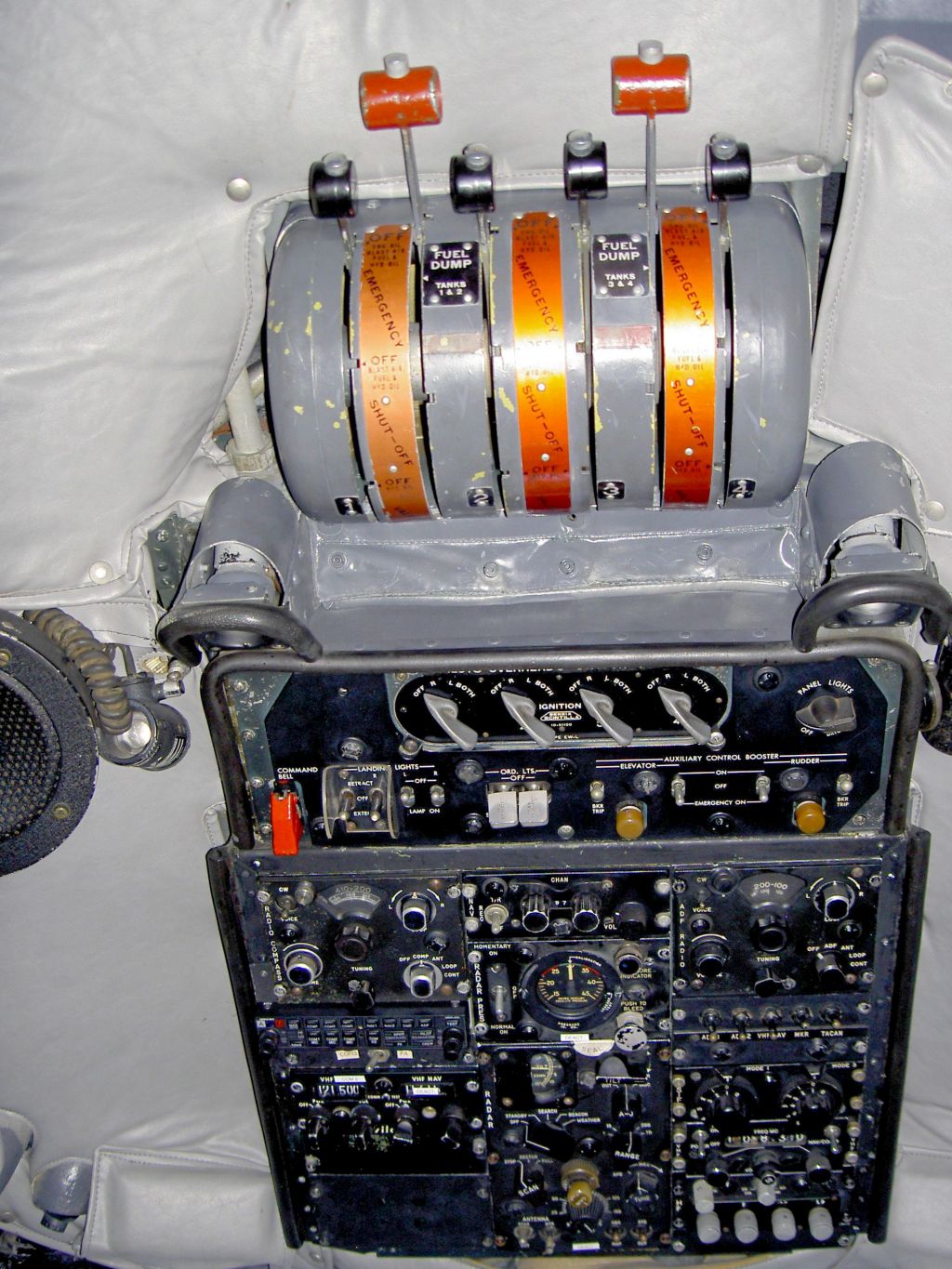

By 8:11 p.m., the crisis seemed over. The engine was feathered, the fire out. But then Garrett realized he’d forgotten the fourth step in fire suppression: shut the inter-engine firewall. Having been recently furloughed by Eastern Air Lines, he was unfamiliar with the Tiger shut-down procedure. He pulled the wrong lever.

So, rather than hear Garrett say “Firewall number three closed,” Murray heard “a shrill obscene snarl from the left side of the airplane, a near-deafening whine, ever increasing in pitch,” followed by Parker yelling: “Runaway on number one!”

Shutting the wrong firewall started a dangerous chain reaction: one of the good engine’s hydraulic subsystems stopped pumping, the blast air stopped cooling its generator, and fuel and oil stopped flowing to the motor and governor. This caused the propellor to spin uncontrollably at close to the speed of sound. If the 13-foot metal blades were to break free, which sounded imminent, the resultant projectiles could down the plane.

Murray muscled all the throttles back to decelerate from 330 to 210 mph, while easing Connie’s nose up to improvise a makeshift brake from the air current. Disaster was averted. The blades slowed just enough to allow Garrett to feather the left outboard engine (No. 1).

But now the plane had lost two engines in seven minutes, 972 miles from land.

Ditching was now a very real possibility. Having flown this route countless times and as an avid student of history, Murray knew what was implicated by the prospect of splashing into the 15 million square miles bounded by Ireland and Newfoundland. The North Atlantic seabed was a mausoleum, home to the remains of Britain’s supposedly unsinkable Titanic, many of Spain’s supposedly invincible galleons, and hundreds of other unfortunate ships and planes.

Murray knew hitting the water would feel like crashing onto a serrated cement runway at 100-plus mph, that the water was bitter-cold, and there were no ships nearby. He knew the likeliest outcomes were that his plane would shatter on impact or sink in seconds, and that every previous attempt to ditch a commercial airliner in such vile conditions had failed in part because most fatalities had resulted not from the impact but afterwards. If he managed by some miracle to get everyone down safely, and evacuated, the reward would be a gauntlet of new hazards ranging from hypothermia to hungry sharks, attracted by the blood and splashing.

The intercom buzzed. It was Sims. Because Murray had asked her to do everything she could think of to create an air of optimism and normalcy, she’d disappeared inside the crew’s curtained-off sleeping area, slipped out of her standard uniform, and emerged wearing her spiffy blue pinafore attire. Sims felt actions spoke louder than words: what better way to convince the anxious passengers that everything would turn out as planned than by serving dinner as planned? However, when she said the other three stewardesses were about to start serving, Murray asked her not to use the ovens and coffee makers, as every ounce of power had to be conserved. Sims said that wouldn’t be a problem as “most of the passengers had lost their appetite.”

All Sims’s terrestrial jobs bored her to tears. The 32-year old Big Apple resident had the flying bug so bad she’d quit Wayne State University less than a year before getting her degree, so she could return to the skies. Having recently (secretly) wed, she was in violation of a personnel policy that also forced stewardesses to retire at 32. When tendering her resignation, she failed to mention her wedding. She wanted one more flight in a Tiger uniform.

Boredom was not an issue now. At 9:17 p.m., most of the passengers seated on the left side of the plane could hear the inboard engine “running wild,” spitting yellow-orange flames and coughing up blue-black globules of carbonized fuel as big as a football helmet. It sounded like the No. 2 might explode any second.

Sims seemed to be everywhere, her demeanor calm, composed, earnest. She’d be heard over the PA system speaking from the fight deck, asking everyone to make sure their overhead bins were empty of all potentially hazardous objects; huddled in the galley, drawing diagrams on the back of the flight manifest, showing how to open the window exits and pull the T-bars so as to release and inflate the wing-stowed rafts; crouched near the rear exit, telling Gould there was no need to search for the first aid kits because she’d already distributed them, along with lots of pocketknives and flashlights; all the while smiling serenely, whispering things like “Don’t panic, because if we do, we’re goners.”

For the next 45 minutes Murray battled high winds and sheets of rain while considering whether to dump fuel, divert, or ditch; as ominous-looking fires kept erupting until doused and earsplitting alarms kept blaring; while the stewardesses drilled the 68 passengers repeatedly.

Murray told Parker, Garrett and Hard Luck Sam that he had to decide how to approach and make impact with the sea. His confused colleagues exchanged puzzled glances. After all, Parker had just read from the manual, which stipulated: “Never land into the face of a swell (or within 45 degrees of it).” These same instructions were found in all the other specs Murray and Parker kept up on: Navy tip sheets, Flight Safety Foundation accident bulletins, Air Line Pilots Association newsletters, Civil Aeronautics Board accident investigation reports.

The pilot explained he wasn’t ignoring the manual, just overriding it. “In almost every ditching training session,” he reasoned, “after a discussion of why it’s better to land parallel to the swells, there’d always be an old-time flying boat captain who landed his Sikorsky or Boeing into the swells.” Plus, “while the Coast Guard’s ditching tests sound sensible in theory, none was conducted with the conditions we’re dealing with.”

Having studied to be an engineer, Murray felt the stiff winds on the surface would reduce his speed and minimize sideways drift; so, absent “a significant change in their direction or velocity, or the primary swell direction or height,” he said he’d do what the flying boat captains did: head into the wind, facing the swells, and touch down between two of them.

But that would be a challenge in the pitch blackness of a North Atlantic gale.

After instructing Sam to sit at the rear of the plane and make sure the emergency inboard raft was launched, and then inflated — for inflating it inside the cabin would block egress, Murray instructed Parker and Garrett to sit by the window exits in row 9, not with him. The copilot and flight engineer protested. The captain said his decision was final.

A Tiger colleague would later say, “All four men knew the nose was the worst place to be. They knew anyone seated there would hit hard, probably be knocked out and might not be able to evacuate. John was essentially saying, ‘I’m expendable but you need to help people off the plane.’ It was the definition what being a captain is all about: going down with your ship.”

In row 13, while helping 9-year-old Luana Hoopi and her 11-year-old sister Uilani don their life vests, Sims asked for a volunteer to escort the girls off the plane and into a raft. There being no takers, the chief stewardess tapped an Army sergeant on the shoulder and locked eyes: Please? He nodded. “Sure. I’ll do it.”

Gould, who’d filled in for a sick colleague at the last minute, arrived at row 8 on the left side of the plane, counted out the 18 passengers she’d been assigned, placed a life vest around her neck, removed the “Always Prepared” ditching pamphlet from a seat back, and introduced herself. “For those I’ve not met, I’m Carol. Carol Gould. I’m a Jersey girl, from Lyndhurst.”

“Can I have your number?” said a paratrooper.

Gould smiled. “Sorry, I’ve got a fella already.”

The suitor snapped his fingers. “Rats.”

Holding out a blanket, Gould walked up and down the aisle, saying, “Please deposit any pocketknives, pens, anything else that could potentially injure you on impact or puncture the raft. Don’t forget your reading glasses, dentures, belts, buckles and boots. A few of the knives will be given back, but Betty wants them all collected, first.”

Paratroopers contorted themselves in their cramped seats in order to unlace and remove their leather boots. They stood, rummaged around, and pulled knives and other items from their rucksacks in the open overhead bins. They unpinned their brass Army Airborne lapel wings.

Lois Elander handed her husband her pierced pearl earrings but kept her wedding ring on and tucked a gold bracelet under her shirt cuff. She didn’t see how these items could hurt anyone and didn’t want to lose them. They meant too much. She also gave Dick the $50 she’d squirreled away to buy something special in Paris.

After stuffing the cash into his pants pocket, Dr. Elander, West Point’s chief of ophthalmology, removed his reading glasses, rolled them up in a sock, and dropped them in the blanket, along with his wife’s earrings.

A few minutes before 10:00 p.m., most aboard felt the muted thump on the left side of the plane, heard the tray tables rattle, and glasses tinkle. Most knew what it meant: the third of four engines (No. 2) had failed. The situation was dire.

Murray brought the mic close to his lips and said: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. We’re going to have to ditch.” As the plane’s landing lights illuminated his approach, he called out over the 121.5 frequency:

Mayday. About to ditch. Position at 2212 Zulu Fifty-Four North, Twenty-Four West. One engine serviceable. Souls on board seventy-six. Request shipping in area prepare to search. Over.

He chopped the No. 4 engine and began easing the Connie down to the waiting sea.

Back in row 20, in accordance with Murray’s instructions, Hard Luck Sam got ready to begin his countdown to impact. Staring out the left window, he saw the huge swells and gnarly whitecaps. He called out loudly so everyone could hear: “Ten . . . nine . . . eight . . .”

PFC Raúl Acevedo, an American infantryman born in Mexico, recalled that “the moments seemed like an eternity.”

“Seven . . . six . . . ”

Across the aisle, PFC Gordon Thornsberry heard Sims point at and say something about the rope that was supposed to anchor the emergency raft to the cabin floor, so when tossed into the sea it didn’t shoot off before it could be inflated. But the Arkansan couldn’t comprehend her over the countdown and “on account I was fixin’ to die.”

“Five . . . four . . . ”

In the cockpit, Murray wasn’t braced. It was too confining. He needed the freedom of motion to react to any last-second exigencies. He ignored his aching forearms and the howling winds. It was just him and the sea.

He could now clearly make out the distance between swells: they looked to be about 200 feet, crest to crest. Given the plane’s 163-foot length he had a 37-foot margin of error; not much, given the fact that his current speed meant Tiger 923 was traveling at 176 feet per second. The waves seemed to be every bit of 20 feet, high and powerful enough to snap both wings off and send the four rafts stowed in their bays to the bottom of the sea.

“Three . . . two . . . ”

As a wind shear slammed into the plane’s right flank, Murray called out: “I’m ditching!”

Then Things Got Really Bad

Murray and everyone else expected the plane to cut into the water and skip at least two, maybe three or more times, like a big pebble on a pond. But the sea was too rough. Seventy-three tons traveling at 120 mph — stopped on a dime.

There was a flash of blue as the right outboard engine clipped a wave. The first rebound snapped off the left wing, the second ripped most of the starboard seats off the cabin floor. The right tail fin hit the water, then the nose. A fuel tank ruptured, sending fuel gushing up through the carpet. A dozen windows imploded: Phoom-phoom-phoom-phoom. Murray’s head hit the glare shield; knocking him out. The landing lights shorted out and the plane began to take on water. It all happened in seconds.

A survivor said it felt and sounded like “just one crashing smash . . .like all the nails in Christendom being pulled out of boards at once.” He went “flying through space, strapped to the seat, as though it had never been bolted to the floor.”

Copilot Bob Parker was unhurt. He unbuckled his seatbelt, rushed up from amidship, and laid his left hand on Murray’s right epaulette. It was sticky with blood. “John?”

The pilot stirred, said he was okay, and told Parker to return to his station. Murray said he’d follow soon.

At the back of the plane, Hard Luck Sam unfastened his seatbelt, grabbed the un-inflated emergency raft with his left hand and with his right hand opened the main cabin door. The ocean roared in: pinning him against the opposite wall. A survivor said later, “It seemed like he’d opened the doors of hell.”

Sam dropped the raft, ducked his head, and raised his arms until the onslaught ebbed, then spat out seawater, again reached for the raft, and tugged at it. No luck.

A soldier rushed back from row 18. He and Sam muscled the rubber mass out the door and into the water.

But as the raft wasn’t tethered to the cabin floor, the wild waves and fast current shot it out to sea. As the soldier stared in horror, the civilian navigator dove after it.

Carol Gould was amazed her only injury was a bruised thumb. She watched from the aisle as one paratrooper yelled “Get on with it!” as two others struggled until they managed to remove an exit window. Once it was removed and she’d stepped over to reach for the T-bar to jettison the two rafts stored in the left wing-bay, three anxious soldiers barreled into her, pushing her toward the exit. She yelled: “No, wait, no, wait! I have to pull this red lever!”

Seeing her being forced out through “a steady wall of water flowing over the window,” a retired Air Force officer yelled: “Stop pushing her!” As he’d later recall: “I pulled one man away, and as I was pulling him, one man got out, the second man got out, and the third got out. Just a matter of seconds. It was one, two, three and they were out.”

Gould clutched the frame with her hands and dug her feet into the sill. The fierce wind blasted her backwards and the freezing sea-spray drenched her. Just before stepping through the window and onto the wing, she looked out and realized: There is no wing!

Another batch of soldiers pressed against her. “Jump, Carol, for Crissakes!”

She replied: “I have to pull the lever!”

As the scrum kept pushing her inexorably out the exit, she couldn’t reach the raft-release lever. She thought: Someone else will have to do it.

“Jump, Carol — dammit!”

She jumped.

A dozen others followed Gould out the left side. None pulled the raft-release lever.

The conditions were nightmarish. No one saw any sign of the four rafts they’d been assured would be bobbing beside the plane, inflated. Most couldn’t inflate their poorly designed, unlit life vests. The water temperature was in the mid-40s; the wind chill below zero. Towering swells rolled in every 9 seconds, swallowing up the flailing evacuees, then spitting them out. Though some planes were orbiting the ditching site at altitudes as low as 1,300 feet, no one could see them. It was pitch-black.

Up in the cockpit, Captain Murray tried to think straight but a split-open skull made it hard. Muddled though his cognition was, he knew he needed to get out fast. He could see the rising waterline through the wraparound windshield.

He listened for voices. Not hearing any suggested most of the other 75 souls had made it off and, perhaps, were safely aboard the five life rafts. He felt thankful for that, as well as for being alive and able to move.

Though the captain was as eager as anyone to get off the rapidly sinking plane, he knew his duty: accounting for every man, woman and child and, if necessary, helping them evacuate and get clear of the plane’s inevitable undertow. Given the rate at which she was taking on water, it was clear to him that the Connie wouldn’t stay afloat much longer. He just wasn’t sure if he had five minutes or five seconds.

Standing up made him dizzy. While leaning into his seat for stability, he paused to feel about for any additional injuries apart from his head, which hurt like hell.

He waded aft. Though it was dark, the small cobalt blue ceiling lights hadn’t zapped out yet and some moonlight refracted off the water through the windows. He could see well enough.

It was slow going. Murray fought his way past the icy sea shooting through the windows and the noisome fuel seeping up through the floor, past the workstations, crew bunks, and galley; then headed down the aisle, glancing left and right, flipping over the occasional uprooted seat. There was no sign of anyone. It was heartening.

It took him about two minutes to make it to the rear of the plane and the main cabin door, which was almost entirely underwater. After stepping up onto the sill and bending his knees, an instant before diving out, an idea seized him: Maybe I should go back for a flashlight?

Though Sims had assured him she’d collected 11 flashlights, who knew how many had made it off the plane? Or how many had sunk? Or how depleted the batteries were?

As he stood in the doorway contemplating the horrible options, a white-shirted silhouette framed by the dark exit, had anyone been looking his way they might well have wondered: what on earth is he waiting for?

First, there was the matter of his even being able to make it back into the cockpit before the plane sank. He’d have to make his way 150 feet in really cold, waist-high water, obstructed by 76 sets of personal belongings and other flotsam.

Second, the sputtering cabin lights seemed ready to give out. He’d lost his prescription eyeglasses. One eye was obscured by blood. Even if he made it to the flight deck and there was a flashlight there, would Murray be able to find it in time?

Yet the pilot turned around, gulped some air, shut his lips, and dove under the water. He powered his way past 100 seats, many overturned and piled high in the aisle; entered the flight deck; swept aside mushy dinner rolls in the galley and waterlogged manuals in the cockpit; and there it was, wedged at the base of the very same glare shield that had knocked him out and split his head open. Murray grabbed the flashlight, turned around, and headed aft.

By now a lot more seawater and fuel had flooded the cabin. Still, he made it back to row 8’s right-side wing exit. More winded than he’d ever been in his life, he tried to catch his breath, ruing his love of Pall Malls. His life vest was on but unclipped. He gripped the sides of the exit, tilted his head up, and gulped some oxygen from one of the few remaining pockets of air. Just as he stepped up onto the sill, a wave crashed through the open window behind him—knocking him overboard.

Murray splashed amidst chaos and pathos: of people crying for help, calling after loved ones, dog-paddling furiously. A few could make out the dark yellow clump skipping away from the plane. Fewer could see the navigator in pursuit. Hard Luck Sam was a good swimmer but he’d never faced water this rough. Though the waves fought his every stroke, after about 10 minutes he’d pulled up beside the raft. As he rested his hand on its side and caught his breath . . . a wave swept it off into the night. He swam after it and grabbed it but couldn’t keep the thing still, let alone inflate it. It was too cumbersome, too slick with aviation fluids, and too elusive in the swift current. It seemed hopeless, a lost cause.

Two soldiers showed up and blocked the raft with their bodies, which allowed Sam to paw about in search of the CO2 releases. But they were hidden by darkness, waves, and folds of rubber.

More paratroopers arrived, attracted by splashes and voices. The added ballast enabled Sam to locate a tab and pull it. The CO2 canister popped and hissed. He found a second tab and pulled it.

It took maybe three minutes for the raft to fully inflate. The men were in no mood to wait, however. They began trying to climb aboard. But there were no handles or rope-braids. The sides were three feet high and extra slippery. Every time someone hooked a leg or an arm over the gunwale, a wave would sweep them back into the water. Soldier after soldier was repulsed.

Then a billowing crest lifted a member of the 82nd Airborne 15 feet up into the air and dropped him down in the center of the raft. He got his bearings, pulled in Hard Luck Sam and two others, and the four began yelling over the roaring wind and crashing waves, trying to alert others to the fact that they’d found, inflated, and boarded one raft at least.

Someone detected the faint rumble of an aircraft’s engines in the sky above, though the plane was hidden by the clouds. He yelled: “Who’s got a flashlight? Let’s send up a flare!”

Sam was supposed to have brought a flashlight, a flare pistol, and extra flares. But all he’d managed to bring were some flare cartridges, which, absent the pistol, were useless.

Then he realized the raft was equipped with a flashlight and a flare pistol. Phew! He told everyone to look around and feel about for the storage compartment.

After a few fruitless minutes, an observant soldier noticed the raft’s oddly sloping interior contours; how, rather than forming a crisp right angle, the sides and floor merged together, more a slope than a perpendicular. “It’s upside down!”

“What?” Sam strained to hear above the din.

“The raft’s upside down! The flares . . . everything else, too . . . are underwater!”

As dozens more arrived and were pulled up and in the raft meant to hold 20, a furious debate ensued as to whether it made sense for everyone to jump back into the water, tip the raft over, then re-board. One PFC spoke for most by yelling: “I’m not sure I could get on a second time!”

There was no consensus but as those opposed to returning to the water were sufficient in number to prevent a flipping, it was settled: the raft would remain upside down. There’d be no access to flares, flashlights, potable water, or medical supplies.

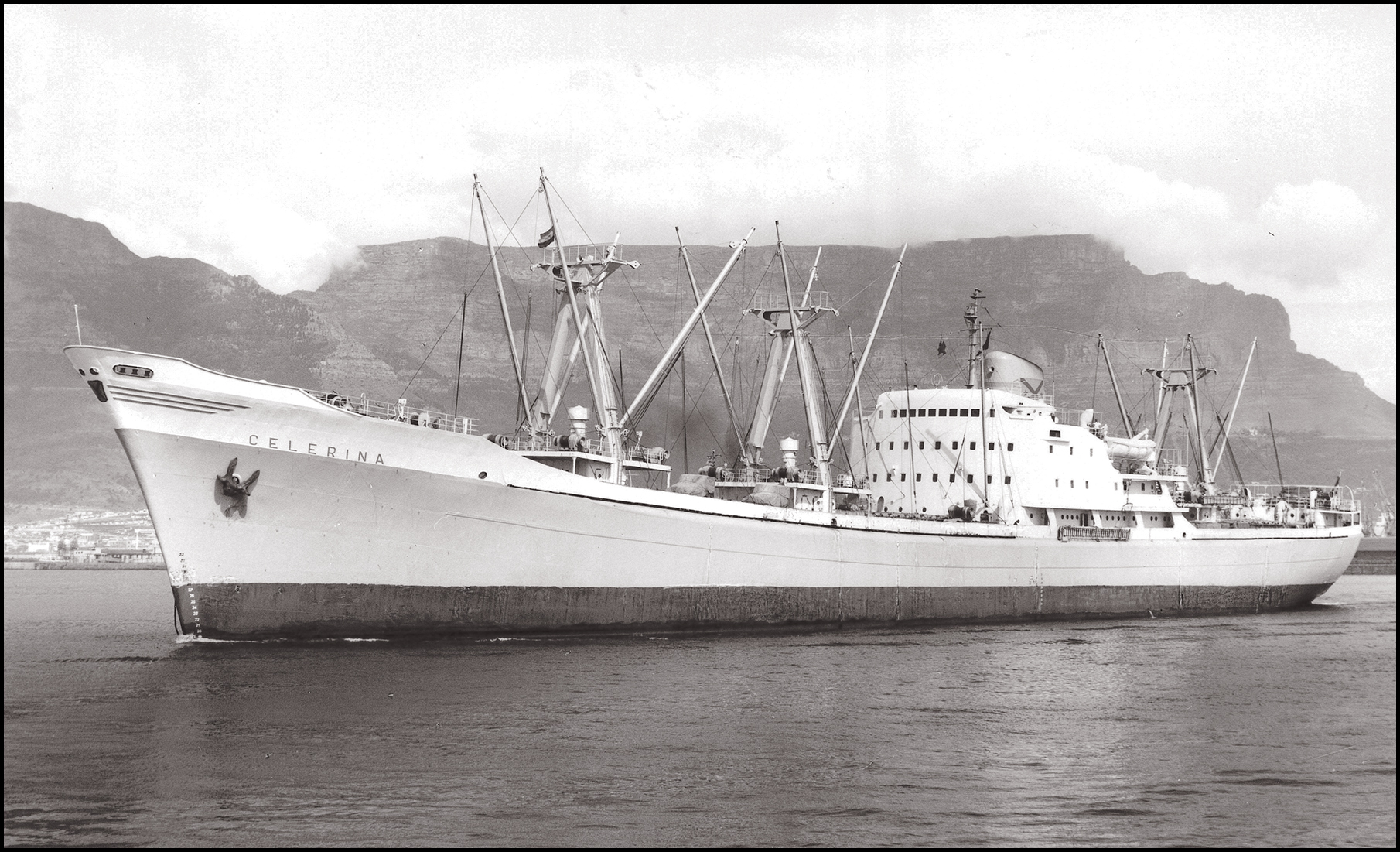

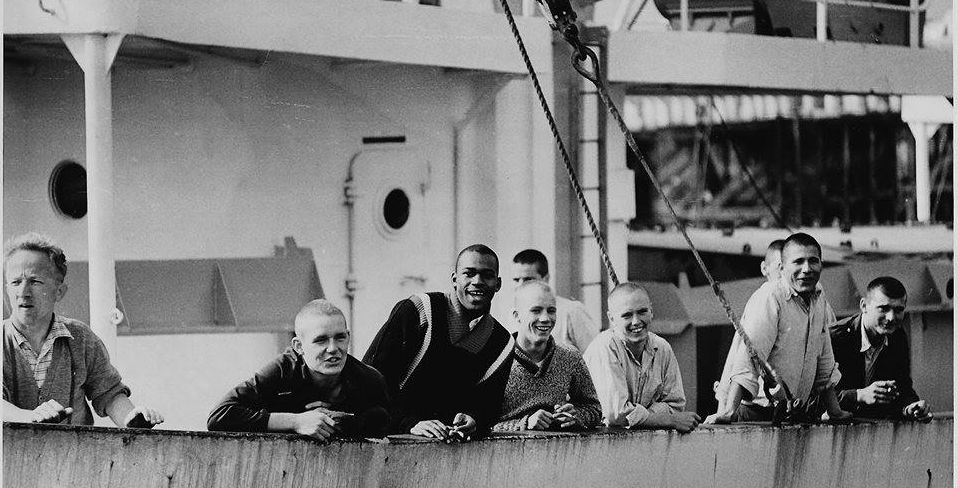

Dozens of ships search for possible survivors from the downed plane

The frantic search-and-rescue operation involved 9 countries, 5 rescue centers, 12 air traffic control centers, 61 military and civilian planes and ships, and more than 10,000 people, ranging from Pentagon telegram operators to 1,200 sailors aboard Bonaventure, Canada’s lone aircraft carrier. Things didn’t go smoothly. A U.S. Air Force pilot said the sea was too “mean-looking” to discern anything. A U.S. Navy pilot added: “I have never seen so many aircraft all working in precision but unfortunately finding nothing.”

One country not involved was the USSR. But it was closely monitoring the situation via its Northern Fleet subs, surface ships, and aircraft; the last thing Moscow wanted was a success. Khrushchev would have loved nothing better than to embarrass President Kennedy and NATO. The way things were going Pravda wouldn’t even need to propagate fake news. Moscow could simply state the truth: “North Atlantic Treaty Organization unable to save soldiers, women, and children in North Atlantic.”

Incompatible communications made matters worse. Since the closest vessel, a Swiss grain freighter, lacked the equipment to patch into NATO’s frequency, over which most of the search-and-rescue updates traveled, its radioman had to try to stay abreast and keep others informed via the antiquated and very slow Morse code, hoping his tap-tapping would be picked up by a nearby ship that had access to the longer-range frequency and could act as a go-between.

Hundreds of millions around the world followed the saga, including President Kennedy. The Army’s vague telegrams did little to allay anxiety. The fate of the 76 souls aboard Tiger 923 was the world’s top news story for days, accorded far more column inches than astronaut John Glenn’s ditching off the Florida coast in April, 1962, or the brewing crises at Ole Miss, in Berlin, and Cuba. After seven hours of terror, 48 survivors were pulled out of the sea.

The Blame Game

Murray was hailed as “The Miracle Pilot” on Swiss TV, German radio, and in Mexican newspapers. However, in the U.S., when a crash investigator was asked what caused the ditching and deaths, he said that because a “triple-engine malfunction is so rare as to be almost unbelievable,” he’d be taking a hard look at the human factor. A panel of political appointees raked the survivors over the coals for 32 hours of public hearings. Murray was fully vindicated.

Tiger 923 was just one of the company’s four Super Constellations lost over the course of 9 months. Yet neither the plane nor the airline was grounded.

But the FAA and Coast Guard modified their ditching procedures in accordance with Capt. Murray’s insight. Tiger 923 also catalyzed many other safety improvements, helping commercial air travel now become 100 times safer than in 1962 (on a per-miles-flown basis).

Semper Fi

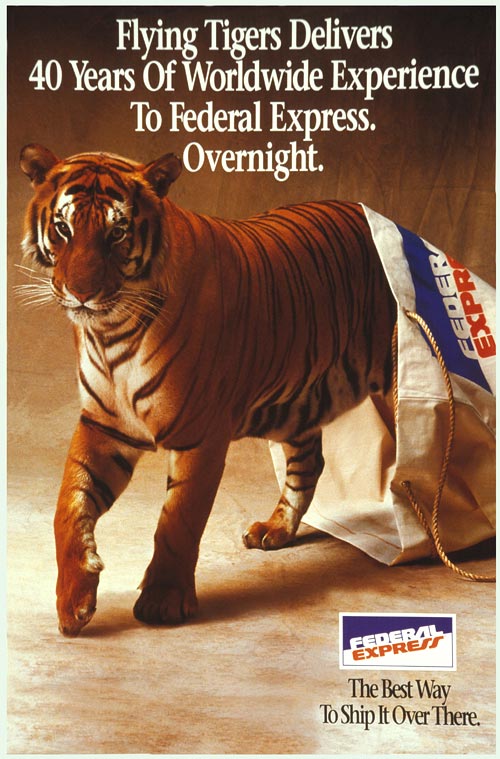

By 1988, Flying Tiger Line that Capt. Murray had flown for was on the ropes. Since the Deregulation Act of 1978, the number of U.S.-based commercial carriers had fallen from 240 to 130. The ones still standing had to scratch and claw for a dwindling slice of the pie, as foreign-flag carriers (most heavily subsidized by their governments) flew nearly 70% of U.S. cargo.

But there were some bright spots in American aviation: notably FedEx, which, two years before the invention of the Internet, had disrupted the postal-logistics paradigm by introducing The Overnight Letter.

FedEx founder Fred Smith — himself a Marine aviator, like many of the Tigers who’d flown for China — realized that behind the airline’s problematic financial statements were some good planes, some proven routes, and a lot of great people; and their “Anything, Anytime, Anywhere” motto meshed well with his own philosophy.

So Smith bought Flying Tiger Line and merged it with his Memphis-based outfit, greatly expanding the Tiger legacy of delivering hope to survivors of natural disasters. The FedEx reach is especially potent during the holidays, when more than 570,000 people power a diverse network of innovative transportation and e-commerce solutions that reaches more than 220 countries and territories, linking more than 99 percent of the world’s GDP, according to the company.

When one of its 680 planes flies overhead, if you listen hard enough, you might even detect a roar.

Copyright © 2021 by Eric Lindner.

Connect with the author on LinkedIn, and tune into The Tiger Gene podcast on Apple, Spotify and Google.