Vladka Meed joined the Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto, eventually escaped, and helped hundreds of children survive Nazi roundups.

-

June 2021

Volume66Issue4

Editor’s Note: William Morrow has just published Judy Batalion’s extraordinary new book, The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos, which has been on the New York Times and other bestseller lists. We are delighted that Dr. Batalion agreed to adapt portions of the book into an essay about Vladka Meed, one of the dozen female resistance fighters profiled in the book, who survived the struggle against the Nazis to emigrate to the U.S. in 1946. Publishers Weekly praised the book, saying it “pays vivid tribute to ‘the breadth and scope of female courage.’”

It would be a grotesque understatement to say the clock was ticking down for Vladka Meed (nee Feigele Peltel), a twenty-one-year-old Jewish woman in the Warsaw ghetto. It was the summer of 1942 and the main Aktion, a Nazi euphemism for the mass deportation and murder of Jews, had begun. It started on “Bloody Sabbath” in April, when SS units invaded the Warsaw ghetto at night and, following pre-prepared lists of names, gathered and then murdered the intelligentsia.

From that moment on, the entire ghetto became a killing field and terror reigned. In June a friend of Vladka’s arrived with news about the existence of Sobibor, yet another death camp, 150 miles to the east. There were rumors of impending doom, stories of roundups, constant shootings. As a member of the Bund, a Jewish socialist party in Poland, Vladka helped print an underground newspaper and disseminate information.

A little boy, a smuggler, told them that the other side of the wall surrounding the ghetto was lined with German and Ukrainian soldiers. Jews were overwhelmed by fear and confusion.

And then the poster appeared.

The Jews crowded into the otherwise deserted streets to read for themselves: anyone who did not work for the Germans would be deported. Vladka spent days scurrying around the ghetto, frantic, looking for work papers, for “life papers” for her and her family. Hundreds of anguished Jews cued up in the scorching heat, pushing, waiting in front of factories and workshops, desperate for any job, any papers. Wagons filled with weeping children taken from their parents passed by.

“Fear of what awaited us dulled our ability to think about anything except saving ourselves,” Vladka later wrote.

Sensing the futility of standing in endless lines, Vladka was elated to receive a message from an underground friend. She was to appear with photos of herself and her family, and would receive work cards. She ran to the address. Inside, thick cigarette smoke and pandemonium. Vladka spotted Bund leaders, and heard about how they’d obtained false work cards and were trying to set up new workshops — all to help save youth. But the leaders felt that hiding was still the best bet, even though being found by the Nazis meant certain death.

And then, panic: the building was surrounded. Vladka ran to grab the falsified work papers and managed to stick with a group who bribed a guard — a common sight as more and more Jews were snatched, and were always resisting in whatever ways they could, Vladka noticed. The deportations went on and on. People waited in terror for their street to be blockaded; then many tried to go into hiding, crawling onto rooftops or locking themselves in cellars and attics.

Jews were urged to appear voluntarily at the umschlagplatz — the departure point from which Jews were deported to death camps — to receive three kilos of bread and one kilo of marmalade. Again, people hoped and believed it was for the best. Many, starving and desolate, keen to stick with family members, went there — and were taken away and killed.

And then, her street. Vladka ran to hide, but a fellow hider decided to open the locked door when the soldiers pounded on it. Resigned to her fate, searching the crowd for her family, who had been hiding a few houses over, Vladka was herded to the “selection,” and handed over a friend’s scribbled work paper. For some miraculous reason, it was accepted. She was sent to the right, to live. Her family, to the left.

Fifty-two thousand Jews were deported from the Warsaw ghetto in the first Aktion. The next day, the members of Freedom, a socialist Zionist youth group who ran underground activities, met with community leaders to discuss a response. They proposed attacking the Jewish police — who weren’t armed — with clubs. They also wanted to incite mass demonstrations. Again, the leaders warned them not to react hastily or upset the Germans, cautioning that the murders of thousands of Jews would be on the young comrades’ heads.

Now, in the face of such mass killing, the youth movements felt that the adults were being outrageous in their overcautiousness.

Who cared if they rocked the boat? They were shipwrecked and sinking fast.

Vladka slips to the Aryan side

Grief-stricken and numb, Vladka went to work in one of the workshops that remained open. The conditions were brutal: exhaustion, beatings, inspections and roundups, hunger and constant terror. Anyone caught idle or who seemed too old or too young to work— death.

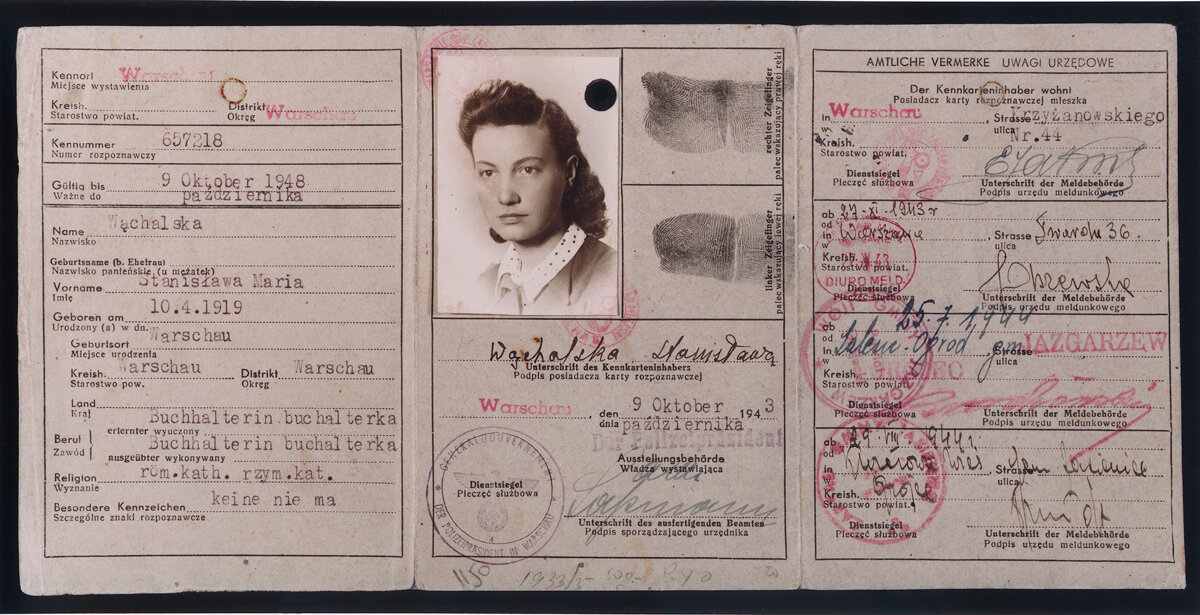

All the while, her fellow Bundists strengthened their fighting units. Vladka was approached by the leader, Abrasha Blum, and invited to a resistance meeting. Because of her straight, light-brown hair, small nose, and gray-green eyes, Vladka was asked to go “undercover,” and illegally move to the Aryan side where she would pretend to be Christian and help the underground effort. The thought of leaving the horrific ghetto filled her with elation.

One night in early December 1942, Vladka received word that she was to exit with a work brigade the following morning and to bring with her the latest Bund underground bulletin, which featured a detailed map of Treblinka. She hid the pages in her shoe, then found a brigade leader who accepted her 500 złotys and slotted her in with the group that was awaiting inspection at the ghetto gate in the freezing cold.

All was well until the Nazi who was inspecting Vladka decided he didn’t like her face. Or, perhaps, liked it too much. She was pulled out of the brigade formation and directed to a small room, its walls lined with splatters of blood and photographs of half-naked women. The Nazi searched her and made her undress.

She just had to keep her shoe on . . .

“Shoes off!” he barked. But just then, another German rushed in to inform her tormentor that a Jew had escaped, and both jetted off. Vladka dressed quickly and slipped out, telling the guard at the door that she had passed inspection. She went on to meet comrades on the Aryan side and began her work establishing contact with non-Jews, finding places for Jews to live and hide, and procuring arms.

The Ghetto uprising begins

When the new Nazi Aktion began suddenly on January 18, the Jewish comrades had no time to convene and decide upon a response. Several members weren’t sure where they were supposed to be stationed. Most units had no access to arms except for sticks, knives, and iron bars. Each group was on its own, unable to connect.

But there was no time to lose. Two groups improvised and launched straight into action. Some of the male and female Young Guard fighters were commanded to go out into the streets, let themselves be caught, and slip in among the rows of Jews being led to the umschlagplatz.

On command, the fighters whipped out their concealed weapons and opened fire on Germans who were marching nearby. They threw grenades at them while screaming at their fellow Jews to escape. A few did. According to Vladka’s account, “The mass of deportees fell upon the German troopers tooth and nail, using hands, feet, teeth, and elbows.”

Needless to say, the rebels’ handful of pistols was no match for the Germans’ superior firepower. The results were tragic, but the influence of these actions was tremendous: Jews had killed Germans.

In Warsaw, underground members on the Aryan side spent months trying to obtain weapons. Posing as Poles, they used basements or convent restaurants for quiet meetings, changing subjects whenever the waitress approached. Vladka Meed began by smuggling metal files into the ghetto — these were for Jews to carry so that if they were shoved onto a train to Treblinka, they could cut through the window bars and jump.

Once, Vladka had to repack three cartons of dynamite into smaller packages and pass them through the grate of a factory window in the subcellar of a building that bordered the ghetto. As she and the Gentile watchman, who had been bribed with 300 złotys and a flask of vodka, worked frantically in the dark, “the watchman trembled like a leaf,” she recalled. “I’ll never take such a chance again,” he mumbled when they finished, drenched in sweat. When Vladka left, he asked her what was in the packages.

“Powdered paint,” she replied, careful to gather up some spilled dynamite from the floor.

Children were often killed first, so were a priority to be smuggled out

Vladka Meed began rescuing children while the ghetto was still intact. The Nazis were particularly brutal with children, who represented the Jewish future. Boys and girls, who were not useful for slave labor, were some of the first Jews to be killed.

Along with two other Bundist couriers — Marysia (Bronka Feinmesser), a telephone operator at the Jewish children’s hospital, and Inka (Adina Blady Szwajger), a pediatrician, Vladka tried to place Warsaw’s few remaining Jewish children with Polish families. These women took children from crying mothers’ arms — mothers who had already saved their sons and daughters time and time again; mothers who knew this might be their final farewell but also knew their kids’ chances of survival were likely better on the Aryan side.

Jewish children had to cross the wall, keep their identities a secret, take on new names, and never mention the ghetto. They could not ask questions or engage in childlike babble. And the host families had to commit and not pull out at the last minute.

After the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, once the ghetto was razed, the resistance workers on the Aryan side were at a loss — the uprising had been their raison d’etre. The stench of burning still lingered, and Germans were everywhere, searching and arresting Poles, killing those who helped Jews.

Several Jewish relief organizations, based on party affiliations, were established, and Zegota (the Council for Aid to the Jews), a Catholic Polish organization founded in 1942, were also hard at work. These organizations found hiding places for Jews, supported them, and helped children. They all received foreign money, some via the Polish government in exile in London. Funds came from the US Jewish Labor Committee as well as the Joint Distribution Committee, which provided over one billion dollars in today’s money to European Jews during the war, helping to finance ghetto soup kitchens and Poland’s Jewish underground.

Vladka’s organization helped thousands of hiding Jews

Rescue groups used the funds to smuggle crucifixes and New Testaments into camps for Jews who wanted to disguise themselves and escape, and to support abortions and procedures that reversed circumcisions. Zegota had a “factory” to forge fake documents, including birth, baptismal, marriage, and work certificates, as well as a medical department with trusted Jewish and Polish doctors who were willing to visit melinas (hiding places) and treat sick Jews.

Vladka found a photographer who could be trusted to come to Jewish hiding places to take pictures for fake documents. She became a main courier for rescue; her organization helped twelve thousand Jews in the Warsaw area.

An estimated twenty thousand to thirty thousand Jews remained in hiding in the Warsaw area, and Vladka’s work spread by word of mouth. Jews found her through a mutual friend, approaching at random on the streets. To receive aid, Jews had to submit a written application detailing their position and their “budgets.” Vladka read through these scribbled appeals.

Vladka moved flats several times. She had hidden the head of the Bund youth movement at her place, and her apartment was “burnt,” or ratted out, by an informant. Three Poles and a uniformed German locked them in the room. Vladka set fire to all her papers, and she and Abrasha tried to escape from the window by climbing down bedsheets, but he was badly wounded. They were both arrested, but comrades bribed the prison guards, and Vladka was released for 10,000 złotys. The Bund leader, however, died.

The movement sent Vladka to the countryside so she’d be forgotten by authorities. Though she felt free in the forest, where she didn’t have to pretend in front of the trees, she found the constant pretense — in particular, spending Sundays at a village church — to be particularly oppressive.

When back in Warsaw, Vladka rented a tiny, dreary apartment passed on by another Jewish courier. The neighbors found out that the former tenant was Jewish and began to suspect Vladka. But if she left, it would reinforce their suspicion and detract from the Aryan identity she’d spent so long cultivating. She stayed and performed as a Catholic: she arranged for a Polish friend, her “mother,” to visit her frequently; she obtained a phonograph and played cheerful music; she invited her neighbors over for tea.

Like Vladka, roughly thirty thousand Jews survived by “passing,” their lives a constant act. Most were young, single, middle-class and upper-middle-class women with “good” Polish accents, documents, and looks. Half were — or had fathers who were — in trade or worked as lawyers, doctors, and professors. More women than men tried to pass because of the relative ease of disguise. Women also asked for help and were generally treated more courteously.

These women lived in a “city within a city, the most underground of all underground communities,” wrote Basia Berman, a leader of rescue efforts. “Every name was false, every word that was uttered carried a double meaning, and every telephone conversation was more encrypted than the secret diplomatic documents of embassies.”

In this constant pageant of deception, Vladka and the Jewish rescue committee had become a family. Many Poles helped them, not for money but out of Christian morals, anti-Nazi sentiment, and sympathy, offering Jews jobs, hiding places, meeting spots, bank accounts, food, and testimony to their “non-Jewishness.”

Vladka makes it to America

Vladka Meed arrived in the United States on the second ship that brought survivors to America, and settled in New York with her husband, Benjamin, who she’d met in the underground. Soon after landing, she was dispatched by the Jewish Labor Committee — which had sent funding to Warsaw — to lecture about her experiences. Both Vladka and Ben were deeply involved in establishing Holocaust survivor organizations, memorials, and museums, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. She was a leader in US Holocaust education.

Vladka organized exhibits about the Warsaw ghetto uprising as well as initiated and directed international seminars about Holocaust pedagogy. Vladka stayed deeply connected to her Bundist roots and became vice president of the JLC, for which she served as a weekly Yiddish-language commentator on WEVD, the New York Yiddish station. Their daughter and son were both physicians.

Vladka retired to Arizona, where she died in 2012, a few weeks short of her ninety-first birthday.