The business of forging George Washington’s signature and correspondence to sell to unwitting buyers goes back 150 years

-

Fall 2011

Volume61Issue2

As the editor of the papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, I have the privilege of intersecting with many people who come bearing documents supposedly signed by the first president. More often than you might think, I have the unenviable task of informing them that their letter‚ often lovingly framed and passed down for decades in their family is a fake. An office file, which we've marked "Forgeries," overflows with dozens of similar examples. Individuals and families are not the only ones duped by what I've discovered has been a robust 150-year-old market in Washington forgeries. Recently a well-meaning alumnus sold a multipage letter apparently in Washington's handwriting to a major university library. The librarians placed the letter on display and trumpeted their acquisition to the media. Several months later, an astute visitor pointed out some strangely awkward flourishes in the letter's handwriting. Upon examination, the letter turned out to be the work of a prolific 19th-century forger.

In the process of amassing more than 135,000 Washington documents, Editor-in-Chief Edward Lengel and other archivists at the Papers of George Washington must remain vigilant against many hundreds of forged first-president correspondence dating back to the mid-18th century.

Just as high demand for popular consumer goods today inspires the production of cheap imitations to satisfy the market, the demand for Washington letters in the mid-19th century inspired the production of thousands of forgeries. Ironically, these fakes are now often collector's items in their own right.

While Washington himself could never have foreseen the emergence of this large, illegal market, he did express the desire that his letters be arranged and preserved. Unfortunately, his family successors at Mount Vernon in the early 19th century did not always honor that wish. They handed out Washington's letters as souvenirs. Visiting scholars took home sheaves of documents, many of which ended up lost or stolen. Thousands of letters that Washington wrote during his lifetime landed in small family collections. Many remain undiscovered to this day, tucked in attics, trunks, files, and library collections across the world.

In the early 19th century, Americans eager to own a piece of the great man's heritage could purchase his original letters in corner bookshops often for just a few dollars. As demand increased, the supply dried up. By the 1850s, casual collectors could no longer easily find or afford to purchase documents bearing Washington's signature. Criminals soon recognized an opportunity.

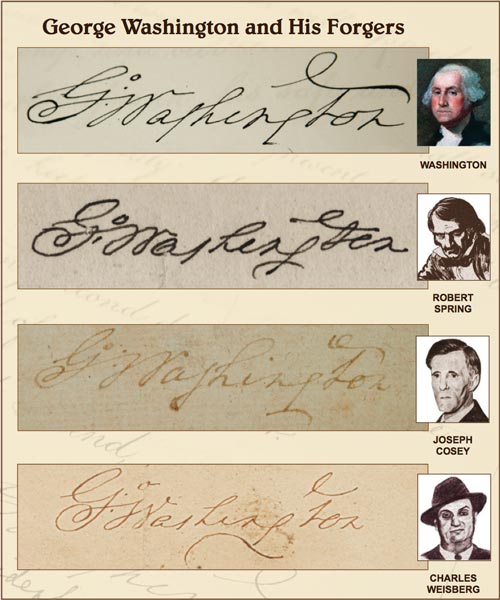

Like many villains throughout history, the British-born Robert Spring could turn on the charm. He immigrated to America as a young man in the 1850s, starting out as a Philadelphia bookseller. He quickly learned that success came by actively appealing to the interests of collectors. At some point he realized that true wealth lay in creating interest where it didn't already exist.

The clever bookseller purchased an armful of volumes that once had belonged to Washington, marked them up significantly, and sold them at a great profit. Pleased with the results, he pulled some dusty, 18th-century books from his back room and lied to customers that Washington had once owned them. They sold as fast as he could put them on display. Spring then began signing Washington's signature on the title pages of some old tomes that he had been trying to unload for years. Customers snatched them up.

If collectors would pay handsomely for books supposedly from Washington's library, and even more for items "signed" by their illustrious former owner, how much more might they part with for letters in Washington's handwriting? Spring had barely needed to convince customers that his items were genuine. Often a little play-acting—volume, then scrawl a letter in handwriting approximating Washington's. Staining the paper with coffee grounds completed the ruse. Spring later discovered a hoard of 18th-century paper that he used to concoct even more convincing forgeries. Sometimes he traced an original Washington letter, often omitting a paragraph or two so that it would fit onto a smaller piece of paper. After a little practice, Spring dispensed with tracing, churning out thousands of letters freehand on his one-man English accent and quietly magisterial personality, customers trusted him. But success soon bred arrogance. No longer bothering to word forged letters creatively, he produced the same documents over and over. One of his favorites was a military pass reading:

"Permission is granted to Mr. Smith with his negro man Tom, to pass and repass the picket at Ramapo.

"Go. Washington"

Spring changed the names on each forgery, but otherwise the content remained the same. A joke later spread that Washington awarded so many passes for the picket at Ramapo that he created the first important traffic jam in American history. Spring's proclivity for forging Washington's bank checks also led some to wonder if the founder had ended his life in bankruptcy.

Spring took special delight in hood-winking so-called experts. One of these was a Philadelphia antiquarian book dealer named Moses Pollock, who prided himself on his "keen scent" for rare books and manuscripts. Before approaching Pollock, Spring studied his victim closely, learning of Pollock's deep pride in his Revolutionary War ancestors. In a backroom at his book shop, Spring cut a blank page from an old tome, dipped a goose quill pen in a special mixture replicating 18th-century ink, and wrote a military pass out to one of Pollock's ancestors.

After seasoning the document, Spring walked into Pollock's Commerce Street bookshop and presented the forged letter. After decades of business dealings, Pollock had trained himself to show little emotion or surprise when approached with a new document. But now he struggled to contain his excitement. "Where did you get this?" he demanded. Spring said he had found it in an old trunk. "How much?" Pollock asked. "To you, Mr. Pollock," Spring replied, "only $15." Pollock was stunned—he could buy a multipage Washington letter for that price—but Spring refused to negotiate, and Pollock paid him.

Many years later, Pollock showed the letter with some pride to the experienced collector Ferdinand Dreer, explaining that Robert Spring had sold it to him. After a glance, Dreer uttered the words that haunt manuscript dealers and collectors: "Mr. Pollock, you, of all men, should know better! This thing is an errant forgery—it's worth less than nothing!"

Spring's crime spree ended briefly in 1859, when a police detective arrested him in Philadelphia. Spring skipped bail and fled to Canada. While in exile he dabbled in mail fraud. Posing as an impoverished collector or a bereft widow struggling to sell her husband's estate, he mailed forged Washington letters to private collectors and asked for $10 or $15 in return. In the 1860s he crossed the border and settled in Baltimore. After the Civil War, he sent letters to British collectors, posing as Gen. Stonewall Jackson's daughter and trying to sell letters supposedly written by Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin.

The authorities caught up with Spring for the final time in 1869. During his trial for forgery, he freely admitted his crimes but protested that he had, after all, made many people happy. How could their ignorance have hurt them? Even so, Spring vowed that he would "rather starve" than return to forgery. After his release from prison, he kept his word. He died in the charity ward of a Philadelphia hospital in 1876.

Spring's sad end did little to deter would-be followers. To the contrary, his early successes inspired them. The mischievous, antiauthoritarian Irishman Joseph Cosey became one of the most distinguished forgers of Washington documents in the 20th century. Born Martin Coneely in Syracuse, New York in 1887, he ran away from home at 17 and hired on as a printer's apprentice. He then joined the army but received a dishonorable discharge after beating up the company cook. A life of petty crime followed, including bouts in jail for passing forged checks. By 1929 he had spent nearly a decade in prison.

That year Cosey walked into the Library of Congress and asked to see a file of historical documents. A librarian cheerfully obliged. Cosey thumbed through them and then left, his pocket stuffed with a souvenir—a copy of a pay warrant signed by Benjamin Franklin. "It wasn't stealing, really," he reasoned, "because the Library of Congress belongs to the people and I'm one of the people."

A few days later he tried to sell the Franklin warrant to a book dealer on New York's Fourth Avenue. The dealer sneered at Cosey and told him it was a fake, which Cosey obviously knew wasn't true. Taking the rejection as a challenge, he spent several months studying the handwriting of major American historical figures so he could create convincing forgeries. He then returned to the same dealer and sold him a forged Abraham Lincoln document for $10.

Like Spring, Cosey cut endpapers out of old books and concocted a formula for "18th-century" ink. (He mixed dime-store ink with rusted iron filings to replicate the dark brown substance used in the 1700s.) But he didn't attempt elaborate schemes, and he usually avoided experienced collectors. He sold his forgeries dirt-cheap, often for no more than a dollar or two, to anyone who would buy them. He didn't expect to get rich; he just got a thrill conning people. He especially enjoyed seeing his creations work their way up to major auction houses, which then sold the fakes for huge sums of money. He didn't begrudge them the profit.

Cosey eventually slid into obscurity, ending his life in alcoholism and drug addiction. His mantle as the prime forger of George Washington documents was taken up by a small-time hoodlum named Charles Weisberg. While an honor student at the University of Pennsylvania, his passion for history and antiques inspired him to forge letters for fun. After graduating, he started furiously forging letters by numerous American statesmen. His favorite was Lincoln, but Weisberg also created a number of Washington items, including fake surveys of Mount Vernon, which he sold for a good profit.

Weisberg's carefully trimmed goatee and his penchant for expensive three-piece suits earned him the nickname "the Baron." After being caught several times for forgery and enduring a series of short prison terms, he adopted aliases to evade authorities. When one of his victims threatened him with prosecution, the Baron fired back: "Anytime you feel like 'taking a swat' at me, I am ready, ready with 225 lbs. of pretty desperate strength, seasoned for five years in as muscle-racking an existence [prison] as a man ever led." But jail was where he ended up; he died at Pennsylvania's Lewisburg Prison in 1945.

Not all of the most prolific Washington forgers labored in the obscurity of petty crime. Poor Italian immigrant Henry Woodhouse (originally Mario Terenzio Enrico Casalengo) arrived in America in 1905, but he soon went to jail after killing a fellow Italian immigrant (he claimed it was by accident). Upon release he learned to fly airplanes and became an aeronautical engineer, a career he translated into great wealth. He began collecting rare historical manuscripts in his spare time. He apparently started forging letters by Washington and others simply to make his own collection seem more impressive, but eventually he began selling the fakes as genuine. Though his work was clumsy, he was never caught. Only after his death in 1970 was Woodhouse exposed as one of the 20th century's most prolific forgers.

Modern-day criminals continue to sell forgeries by Spring, Cosey, Weisberg, and Woodhouse as the real things. Manuscript dealer Charles Hamilton once recognized a Cosey forgery of a draft of the Declaration of Independence in Thomas Jefferson's handwriting. In 1969 Hamilton offered the item for sale in his auction catalogue, correctly describing it as a forgery. He sold it for $425. Six months later a Virginia college informed Hamilton that the purchaser had offered the forgery as genuine for $35,000.

The trade in historical manuscripts has become more lucrative than ever before, with documents written by the founders routinely selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars and sometimes more. While major auction houses and manuscript dealers can usually be trusted to root out forgeries, the proliferation of online auction sites such as eBay has made it easier for cheats, and sometimes well-meaning individuals, to sell phony documents to amateur collectors. There is evidence that some 21st-century criminals are experimenting with new digital technologies for perpetrating fraud.

Throughout the history of George Washington forgeries, there have been two constants: Americans' continuing fascination with the Founding Father, and our substantial capacity for self-deception.