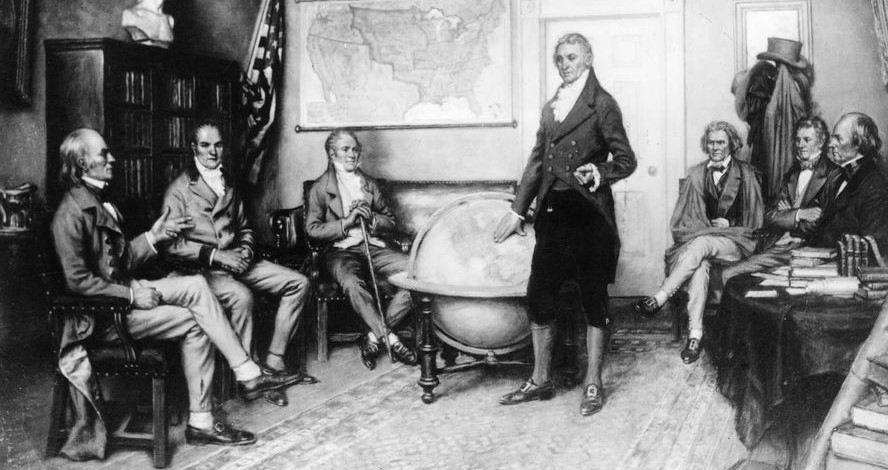

The 5th president's policies helped create an “Era of Good Feelings,” a prosperous time never seen before or since in American history.

-

Spring 2021

Volume66Issue3

Editor's Note: Harlow Giles Unger is the author of twenty-eight books, including more than a dozen biographies of America’s Founding Fathers. He adapted this essay for American Heritage from his best-selling book The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a Nation's Call to Greatness.

“You infernal scoundrel,” Crawford shook his cane menacingly at the president. James Monroe reached for the tongs by the fireplace to defend himself, as Navy Secretary Samuel Southard leaped from his seat and intercepted Crawford, pushing him away from the president’s desk and out the door. It was a terrifying scene: the president — the presidency itself — under attack for the first time in American history.

Twenty years younger than the president, South Carolina’s William H. Crawford had emerged from a new generation of politician — ready to plunge the nation into civil war to promote sectional interests and personal ambitions. Unlike Monroe and the other Founding Fathers, Crawford’s generation had not lived under British rule; had not battled or shed blood in the Revolution; had not linked arms with men of differing views to lay the foundation of constitutional rule.

James Monroe was the last of the Founding Fathers — dressed in outmoded knee breeches and buckled shoes, protecting the fragile structure of republican government from disunion. Born and raised on a small Virginia farm, Monroe had fought and bled at Trenton as a youth, suffered the pangs of hunger and the bite of winter at Valley Forge, galloped beside Washington at Monmouth.

And when the Revolution ended, he gave himself to the nation, devoting the next forty years to public service, assuming more public posts than any American in history: state legislator, U.S. congressman, U.S. senator, ambassador to France and Britain, minister to Spain, four-term governor of Virginia, U.S. secretary of state, U.S. secretary of war, and finally, America’s fifth president, for two successive terms.

Recognized by friends and foes alike for his “plain and gentle manners” in the privacy of his home or office, Monroe proved a fearless and bold leader in war and peace. A champion of the Bill of Rights, Monroe fought the secrecy rule in the U.S. Senate, opening the halls of government to the eyes, ears, and voices of the people for the first time in history. As governor of Virginia, Monroe brought education to illiterate children by establishing the first state-supported public schools, and he enriched their parents with a network of publicly built roads that let them speed the products of their labor to market.

Sent to France as George Washington’s minister during the French Revolution, Monroe saved Tom Paine’s life, then risked his life smuggling the Lafayette family out of France. A decade later, as President Jefferson’s minister to France, Monroe engineered the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the size of the United States without firing a shot and extending American territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains. As secretary of war in the War of 1812, he all but charged into battle to try to prevent the British from burning the Capitol and the White House.

Elected fifth president of the United States, Monroe transformed a fragile little nation — “a savage wilderness,” as Edmund Burke put it — into “a glorious empire.” Although George Washington had won the nation’s independence, he bequeathed a relatively small country, rent by political factions, beset by foreign enemies, populated by a largely unskilled, unpropertied people, and ruled by oligarchs who controlled most of the nation’s land and wealth.

Washington’s three successors — John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison — were in many ways caretaker presidents who left the nation bankrupt, its people deeply divided, its borders under attack, its capital city in ashes. Monroe took office determined to lead the nation to greatness by making the United States impregnable to foreign attack and ensuring the safety of Americans across the face of the continent. He expanded the nation’s military and naval power, then sent American troops to rip Florida and parts of the West from the Spanish, extending the nation’s borders to the natural defenses of the Rocky Mountains in the West and the rivers, lakes, and oceans of the nation’s other borders.

Secure that they and their families and properties would be safe, Americans streamed westward to claim their share of America, carving farms out of virgin plains, harvesting furs and pelts from superabundant wildlife, culling timber from vast forests, and chiseling ore from rich mountainsides. In an era when land — not money — was wealth, the land rush added six states and scores of towns and villages to the Union and produced the largest redistribution of wealth in the annals of man. Never before had a sovereign state transferred ownership of so much land — and so much political power — to so many people not of noble rank. For with land ownership Americans gained the right to vote, stand for office, and govern themselves, their communities, their states, and their nation.

To ensure the success of the land rush and perpetuate economic growth, Monroe promoted construction of roads, turnpikes, bridges, and canals that linked every region of the nation with outlets to the sea and to shipping routes to other continents. The massive building programs transformed the American wilderness into the most prosperous and productive nation in history, generating enough wealth to convert U.S. government deficits into large surpluses that allowed Monroe to abolish all personal taxes in America.

Monroe’s presidency made poor men rich, turned political allies into friends, and united a divided people as no president had done since Washington. The most beloved president after Washington, Monroe was the only president other than Washington to win reelection unopposed. Political parties dissolved and disappeared. Americans of all political persuasions rallied around him under a single “Star-Spangled Banner.” He created an era never seen before or since in American history — an “Era of Good Feelings” that propelled the nation and its people to greatness.

Secure about America’s military and naval power, Monroe climaxed his presidency — and startled the world — by issuing the most important political manifesto in American history after the Declaration of Independence: the Monroe Doctrine. In it, Monroe unilaterally declared an end to foreign colonization in the New World and warned the Old World that the United States would no longer tolerate foreign incursions in the Americas. In effect, he used diplomatic terms to paraphrase the rattlesnake’s stark warning on the flag of his Virginia regiment in the Revolutionary War: Don’t Tread on Me!

Although fierce in the face of enemies, Monroe hid what one congressman called a “good heart and amiable disposition” behind his stony facial expression. His courtship of the stunningly beautiful Elizabeth Kortright is one of the great — yet little known — love stories in early American history. All but unknown to most Americans, Elizabeth Monroe was America’s most beautiful and most courageous First Lady. All but inseparable from her husband, she traveled with him to France during the Terror of the French Revolution, then braved Paris mobs by herself to free Lafayette’s wife from prison and the guillotine. A New York sophisticate with exquisite taste, Elizabeth Monroe filled the White House with priceless French and American furnishings and set standards of elegance that transformed it into the glittering showplace it remains today. The wedding of the younger Monroe daughter was the first ever held in the White House.

Eventually, James Monroe became a victim of his own patriotism, optimism, and generosity, however. Like his idol George Washington, Monroe ignored the costs of his service to the nation. He refused any pay in the Revolutionary War and later spent tens of thousands of dollars of his own funds to promote the nation’s interests during his years as a diplomat, cabinet officer, and president.

No longer peopled by men of honor, Congress delayed repaying him for so long that he, like Jefferson, had to sell his beautiful Virginia plantation to pay his debtors. Failing health and the death of his beloved wife in 1830 left him a broken man — emotionally and financially. He went to live with his younger daughter in New York City, where he died a year later, all but penniless — a tragic victim of his love of country.

Thirty years after he died, Monroe’s successors — sectarian politicians like South Carolina’s vicious cane-wielding Crawford — rent the nation’s fabric in a Civil War that all but destroyed the governmental masterpiece the Founding Fathers had created. But as the wounds of war healed, Americans could still look to the vast western wilderness that James Monroe had opened for his countrymen to build new homes, new towns, and a new, stronger, united nation.

The spirit of America’s last Founding Father still beckoned to them to join the nation’s march to greatness.