Our most talented writer-president always wrote his own material and sweated hours over it

-

Winter 2009

Volume58Issue6

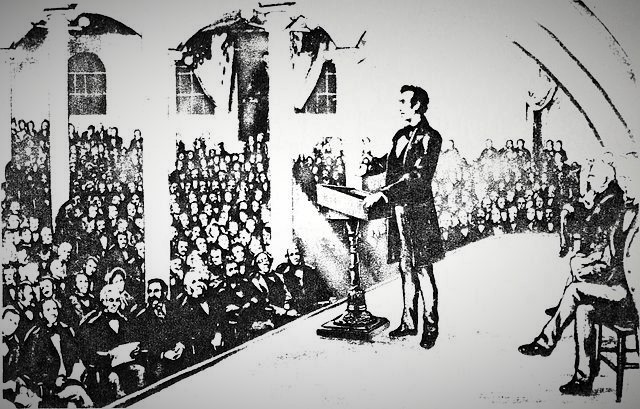

On February 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln stood before a crowd of 1,500 at Cooper Union Hall in New York City. Until he had declared his candidacy for President of the United States, the former one-term Congressman had drawn little attention outside his home state of Illinois. Now the rail-thin prairie lawyer attracted a sizeable audience, including the “pick and flower of New York culture,” along with an army of journalists eager to record and reprint his words.

“Let us have faith that right makes might,” Lincoln challenged his listeners, “and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” Here was no stump speech, but rather a powerful argument that extending slavery to new territories was not only wrong but also counter to the intent of the founding fathers. His delivery was eloquent, the argument carefully reasoned and fact-filled.

Had Lincoln not delivered such a triumphant address before the sophisticated and demanding audience that night, it is possible that he would not have been nominated, much less elected, to the presidency the following November. And had Lincoln not won the White House in 1860, the United States—or the countries it might have fractured into—would probably look very different today.

How Lincoln crafted this brilliant and critical delivery has remained the topic of some debate over the years in part prompted by an interaction he had the following month. Lincoln had traveled from Springfield to Chicago to appear in what turned out to be his last big trial: the famous "sandbar case," a complex civil dispute in which he represented his most important client, Illinois Central.

While in the city, Lincoln also agreed to sit for a wet-plaster life mask at the studio of sculptor Leonard Wells Volk. Chatting in the studio, their conversation turned to Lincoln’s nationally noticed appearance in New York a few weeks earlier. As Volk remembered it, Lincoln told him the astonishing fact “that he had arranged and composed this speech in his mind while going on the cars from Camden to Jersey City.”

By the time Volk published this revelation, almost as a postscript, in his engaging 1881 reminiscence of the sitting, Lincoln’s myth-worthy creative acumen and almost saintly self- effacement had emerged as crucial elements of the reigning image of the Great Emancipator. Volk’s recollection about the Cooper Union speech, clouded though it may have been by the passage of time, seemed well in keeping with the hagiography of the day. Besides, an orator who had supposedly been able to pronounce his masterful 1861 farewell to Springfield extemporaneously, or to create his greatest masterpiece on the back of an envelope while riding on a train to Gettysburg, surely could have written his Cooper Union address on a train in the few hours from Camden to Jersey City.

Of course, like the farewell address and Gettysburg legends, the Cooper Union story was entirely false, though one should not automatically exonerate Lincoln from the small crime of promulgating it. Lincoln cultivated his “modest man” image whenever it might serve: as presidential candidate, Republican nominee, president-elect, and chief executive. For the record, Lincoln delivered a reasonably cogent farewell speech in 1861 off the cuff, but then massaged it into a sublime masterpiece later at the urging of reporters. He wrote at least three drafts of the Gettysburg Address, and tested it out on at least one visitor, before deeming it finally ready for delivery. Few contemporaries knew these details. Thus it is not at all difficult to imagine his accepting a compliment about his recent triumph by protesting amiably that he had dashed it off at the last minute. Volk’s version of Lincoln’s creation of Cooper Union speech was particularly ironic, however, since Lincoln had never labored over an address as diligently, and over such an extended period, as he did to prepare for this engagement at New York.

Writing eight years later, Lincoln’s longtime law partner, William H. Herndon, set the record straight: Lincoln had devoted an enormous amount of time to “careful preparation” of his lecture between his acceptance of the invitation and his journey east. “He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library, and dug deeply into political history. He was painstaking and thorough in the study of his subject.”

His subject, of course, was slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, then six years old, had supervened the Missouri Compromise, which had kept the lid on the smoldering slavery cauldron for more than 30 years. The Supreme Court’s bitterly contested Dred Scott ruling—“a decision,” not a “dictum,” as Lincoln would later argue—had been rendered three years earlier. And it was only two years since the Lincoln-Douglas debates, at which Lincoln had carried his arguments against the expansion of slavery to new heights, his electoral defeat notwithstanding.

Such was the grave, brooding juncture of events when Lincoln came east. But from the moment he was asked to speak at Henry Ward Beecher’s church in Brooklyn (a venue only later shifted to Cooper Union in Manhattan), he determined that his address there would be a political “lecture,” not a stump speech. He would prove historically what he extension of slavery was not only wrong, but counter to the hopes and dreams of the founding fathers. And he would demonstrate moreover that recent efforts to nationalize slavery, like Dred Scott v. Sandford , were, as he first argued in 1857, “based on assumed historical facts which were not really true.”

To construct his speech as a historical and political lecture kept faith with the spirit of the invitation, the integrity of the series of which his lecture was supposed to be a part, and the sacredness of the intended venue: Plymouth Church, an abolitionist shrine. Moreover it promised the chance to reinvigorate, and perhaps crown, Lincoln’s bumpy career as a professional lecturer, which had seen more failures than successes and had embarrassed him before his friends. Finally, it offered him the opportunity to approach the wrenching issue of slavery from a new and challenging perspective: using the lessons and precedents of the American past.

It also called for inordinate toil. Unless we accept Herndon’s account at face value, no one really knows precisely when the idea for a lecture on political history first gripped Lincoln. But once he settled on it, he realized that he would have to work terribly hard if he was to unearth the sources necessary to support his case. He employed no researchers to check references, no speechwriters to compose drafts. Lincoln wrote all of his orations himself, pen to paper, word by word. As his friend and former law partner Ward Hill Lamon noted, “no effort of his life cost him so much labor as this one.”

A possible witness to those tense days was Henry Bascom Rankin, who claimed to have served as a young clerk in the Lincoln-Herndon office. Although he may have later exaggerated his professional connection, Rankin surely saw the pair and he recalled that “Herndon’s patience was tried sorely at times" as Lincoln progressed “very slowly on the speech . . . loitering and cutting, as he thought, too laboriously” Census records show that Rankin was actually employed in early 1860 as a farmhand in nearby Petersburg, but it is certainly possible that he saw Lincoln in the capital from time to time, or heard from people about how the speech was prepared.

For three or four months, Rankin later testified, Lincoln worked assiduously at “writing and revising his great speech.” He “spent most of his time, at first, in the study and arrangement of the historical facts he decided to use. These he collected or verified at the State Library” Lincoln also liked to talk and read aloud to gauge the reaction of potential audiences, and supposedly he held “frequent” discussions with Herndon “as to the historical facts and the arrangements of these in the speech.”

Lincoln might have stepped into the adjacent office of a fellow lawyer to go over one detail or another. Rankin, who insisted that he was “privileged to be present” on such occasions, seemed sure that Lincoln “devoted more time to the speech than any he ever delivered.” No one, not even verifiable eyewitnesses, ever contradicted him.

Whatever his access, Rankin was correct that Lincoln’s meticulous preparation demonstrated not only “the great grasp he had acquired in the discussion of political events,” but “his peculiar originality in moulding sentences and paragraphs.”

Going by contemporary accounts of his work habits, it is easy to imagine Lincoln grappling with his theme: bent over a table, pen in hand, squinting in the gaslight as he sat before piles of massive old volumes inside the handsome law library on the first floor of the state house across the square. Here, his head characteristically resting on his thumb, his index finger curved across his lips and up the side of his nose, his other fingers tightly clenched, he pored over law and history books with intense concentration. When engaged in writing, whether at his small desk in his bedroom at home, in the law library, or in his noisy office, he would set an elbow on the table, place his chin in his hand, and “maintain this position as immovable as a statue” for up to half an hour at a time, lost in thought.

Volk’s report of how casually Lincoln had brushed off the Cooper Union speech appalled Rankin, who charitably dismissed the sculptor’s reminiscence as “an unfortunate lapse of memory.”

On this subject, Rankin and Herndon uncharacteristically found themselves in complete agreement—no small feat, considering that Rankin detested Herndon, and the feelings, if Herndon harbored any, were probably mutual. Subsequent generations of historians have occasionally questioned the accuracy of both men’s recollections, Rankin’s especially. In the final analysis, whether or not he knew the future president as well as he claimed, Rankin is certainly believable about the effort that the Cooper Union address caused Lincoln.

Another sculptor left far more believable testimony about Lincoln’s penchant for preparation. In late January and early February 1861, the president-elect began posing for Thomas Dow Jones, who had been commissioned by his Ohio patrons to execute a bust of Lincoln. The busy politician had little time to sit, but he agreed to visit Jones’s Springfield hotel room for an hour or so each morning, letting the sculptor work on a clay model while he opened his daily mail and did other paperwork.

At some of these sittings, Jones noticed Lincoln slowly writing on long sheets of lined paper. He discovered that the president-elect was drafting passages for some of the speeches he would be expected to make at his upcoming stopovers at Indianapolis and other cities on the journey to his inauguration. Although some eyewitnesses to these orations later criticized the talks for what they took as an all-too¬rambling spontaneity, in truth, Lincoln worked assiduously at his arguments for an orderly presidential transition.

Nearly three years later, Lincoln delivered yet another carefully prepared speech—at Gettysburg. A Massachusetts newspaper noted that while “strong feelings and a large brain" had been its parents, “a little painstaking” had served as its “accoucheur.” Accoucheur is a French word, archaic even in Lincoln’s day, that described the assistant to a doctor or a midwife at childbirth. The journalist who revived the word perceptively (if pompously) observed that even a brief speech like the Gettysburg Address required “work, work, work”—words Lincoln once used to advise an aspiring law student about his career.

The Cooper Union speech had required much more than “a little painstaking” as its accoucheur. It had called for exhaustive scholarly investigation. And it required a distinctively cool and dispassionate approach—not quite reaching the depth of feeling later voiced at Gettysburg, but elevated beyond the kind of partisan invective that had characterized Lincoln’s earlier campaign speeches. As a singular summons requiring a once-in-a-lifetime approach, Cooper Union required—and elicited—from Lincoln burdensome research, cogent legalistic argument, and physical labor on a level he never before or again approached. That exhaustive research and solitary speechwriting became for Lincoln the rule, not the exception, marks him as one of the most gifted and dogged of all writer-presidents.