Although his flamboyant successor, Theodore Roosevelt, largely overshadowed him, William McKinney deserves credit for establishing the U.S. as a global power, acquiring Hawaii and Puerto Rico, establishing the “fair trade” doctrine, and paving the way for TR’s accomplishments.

-

Spring 2018

Volume63Issue1

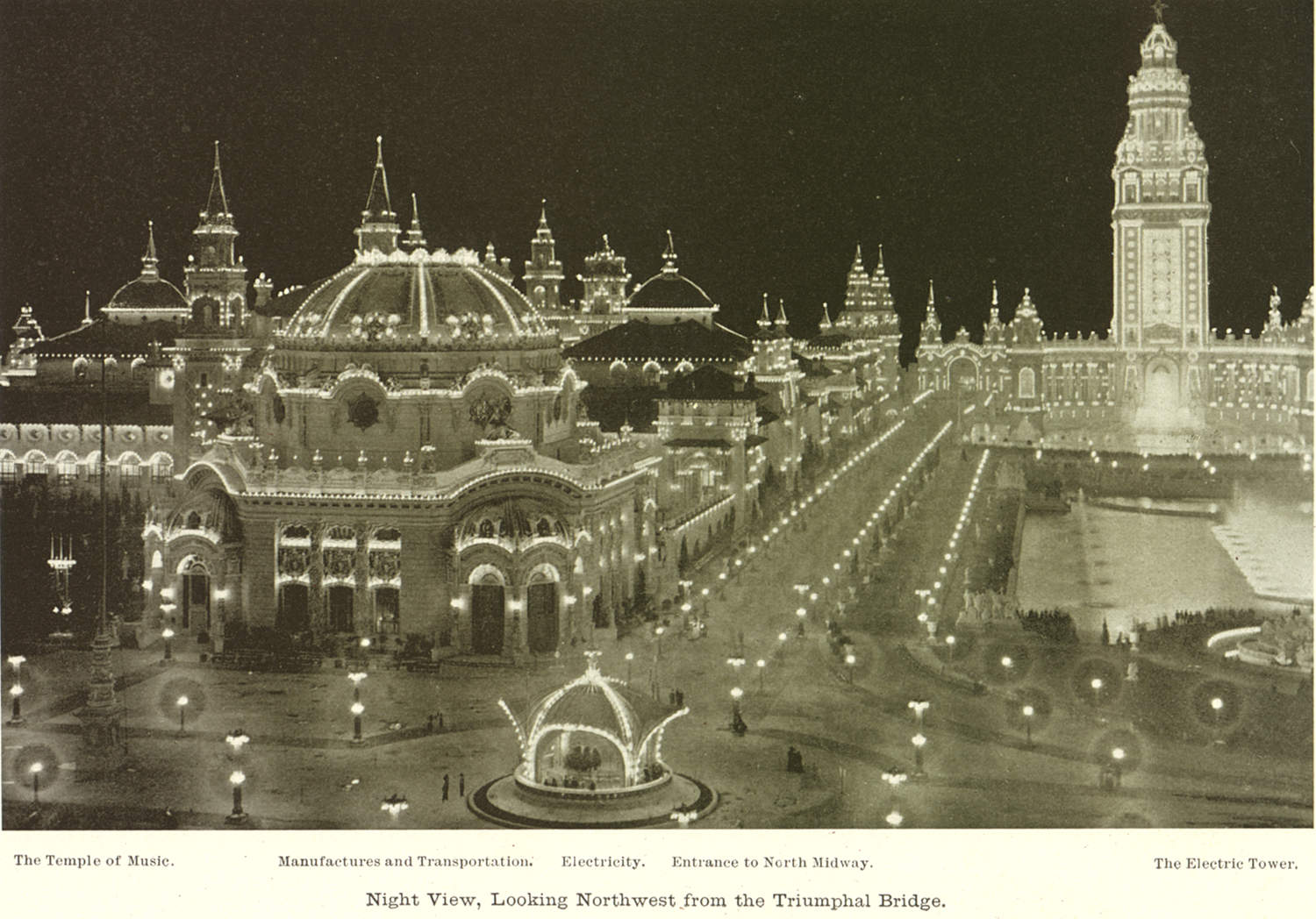

President William McKinley arrived in Buffalo, New York, on the evening of September 4, 1901, intent on deflecting history with a speech. The Ohio politician's shiny and luxurious presidential train crawled into the city's Terrace Station at six-thirty that evening, and the presidential party moved quickly toward waiting carriages near the north gate of the Pan-American Exposition, an attention-grabbing extravaganza that had opened its doors on May 20. It featured exhibits, spectacles, musical performances, athletic events, and more—most notably, displays of the latest technological wonders, including an X-ray machine and the startling advent of alternating current, allowing the efficient transmission of electricity through long-distance power lines. This promising advance brought enough power to Buffalo from Niagara Falls turbines, twenty-five miles away, to illuminate the entire exposition grounds in a nighttime display of electrical wizardry.

Under McKinley, America was developing and harnessing technology like no other nation, generating unparalleled industrial expansion and wealth, moving beyond its continental confines and into the world. It wasn't surprising that Americans would flock to the Buffalo exposition—an estimated eight million or more over six months

This was just the kind of marvel to capture the imagination of a nation on the move, pushing into the twentieth century as it had pushed westward across North America during the previous hundred years—with resolve, confidence, and disregard for accompanying hazards. Now, under McKinley, America was developing and harnessing technology like no other nation, generating unparalleled industrial expansion and wealth, moving beyond its continental confines and into the world. It wasn't surprising that Americans would flock to the Buffalo exposition—an estimated eight million or more over six months—to bask in their country's promise, or that Exposition leaders would designate a special day to honor the president. Neither was it surprising that McKinley would choose that day to summon support for a major policy departure for America—and for himself. The Pan-American Exposition represented a fitting convergence of the man, the event, and the era.

No development defined the era more clearly than the rise of America as a global power. This came about mostly through the brief, momentous war with imperial Spain two years earlier—"a splendid little war," as historian and diplomat John Hay called it. When it was over, Spain no longer possessed a colonial empire of any consequence, and America had planted its flag upon the soil of Cuba (as a temporary protectorate) and upon Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines (as permanent possessions). For good measure, the country acquired Hawaii, one of the most strategic points on the globe, a kind of Gibraltar of the Pacific. In addition, the country was building a navy to rival the great navies of the world and demonstrating a capacity to deploy troops quickly and effectively to far-flung lands.

American economic and diplomatic power also surged. U.S. goods, both manufacturing and agricultural, were being gobbled up in overseas markets, and this burgeoning export trade promised ongoing U.S. prosperity. President McKinley was discovering, moreover, that this new military and economic might had rendered America a nation to be reckoned with. Just the year before the country had nudged the major European powers and Japan toward a collective policy in China—favorable to U.S. interests and conducive to regional stability—that most of those countries didn't particularly like.

As for the event, the Pan-American Exposition sought ostensibly to foster and celebrate a kind of diplomatic and economic brotherhood among the nations of the Americas. Indeed, when John Hay, as secretary of state, visited the Exposition the previous June, he titled his remarks "Brotherhood of the Nations of the Western World." But, as the New York Times noted, America's relations with its Western Hemisphere neighbors often reflected "unconcealed haughtiness mingled with something not unlike greed." And Hay's remarks, notwithstanding his title, seemed less a celebration of any kind of brotherhood than of American grandeur, reflected in his paean to "this grand and beautiful spectacle, never to be forgotten, a delight to the eyes, a comfort to every patriotic heart that during the coming Summer shall make the joyous pilgrimage to this enchanted scene."

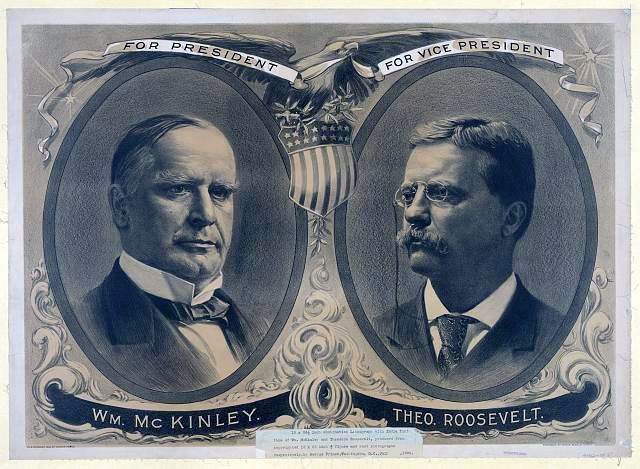

Then there was the man, fifty-eight years old at the time of the Buffalo Exposition, now five months into his second presidential term. To his detractors, William McKinley seemed an unlikely figure to be presiding over the transformation of America. In this view, the affable, stolid, seemingly plodding McKinley hadn't really led America through the momentous developments of his presidency but rather had himself been manipulated by events beyond his control. And yet nobody could dispute his political popularity. His 1900 reelection margin exceeded the margin of all recent presidential victories. And even getting reelected at all marked a notable political achievement in an era with few two-term presidencies. Many in McKinley's day argued that his commanding position atop the country's political firmament testified indisputably to his political effectiveness and brilliance. But others dismissed that view as fanciful. They insisted on judging him as unequal to his deeds.

That was the mystery of William McKinley, which baffled many contemporaries as it would intrigue subsequent generations of historians and biographers. The wife of a prominent Ohio politician—alternately a McKinley ally and rival—referred to "the masks that he wore." A later historian of the period called him "a tantalizing enigma." The enigma was this: How did such a man manage to preside over such a national transformation? Or did he?

Short of stature, with broad shoulders and a large, expressive face, McKinley peered at the world through deep-socketed gray eyes that seemed almost luminescent. Kindly and sweet-tempered, he once invited into his closed carriage, during a downpour, a hostile reporter who had been attacking him in print throughout a congressional re-election campaign.

"Here, you put on this overcoat and get into that carriage," he told the rain-soaked journalist.

"I guess you don't know who I am," replied the surprised scribe. "I have been with you the whole campaign, giving it to you every time you spoke and I am going over to-night to rip you to pieces if I can."

"I know," said the congressman, "but you put on this coat and get inside so you can do a better job."

Such self-effacing solicitude, so natural in McKinley and rare in most high-powered men, led some to conclude this congenial politician lacked the cold instinct for audacious and functional leadership. Further, his intellect did not display an imaginative turn of mind given to bold thinking or creative vision. Rather, McKinley possessed an administrative cast of mind, focused on immediate decision-making imperatives. He was cautious, methodical, a master of incrementalism. Such traits contributed to the McKinley mystery. He never moved in a straight line, seldom declared where he wanted to take the country, somehow moved people and events from the shadows. He rarely twisted arms in efforts at political persuasion, never raised his voice in political cajolery, didn't visibly seek revenge. And yet he seemed always to outmaneuver his rivals and get his way. How did this happen?

It happened through some powerful yet opaque McKinley traits, most notably his ability to comprehend the intricacies of events as they unfolded and mesh them conceptually into effective decision making that moved the country in significant new directions. He had learned through a lifetime of politics that his quiet ways somehow translated into a commanding presence; his was a heavy quiet that could be exploited stealthily. Throughout his early days in the military, as a lawyer, and in politics, he could see that men responded to him and looked to him for leadership. Further, though a man of deep convictions, he developed a flexibility of mind that prevented dogma from thwarting opportunity. He struggled manfully to avoid the war with Spain, for example, but when that proved impossible he prosecuted it with a vigorous resolve to crush the Spanish Empire and kick it out of the Caribbean. Following the Spanish defeat, he hesitated on what to do with the Philippines but eventually concluded the only realistic course was acquisition of the entire archipelago. So he took it and never looked back.

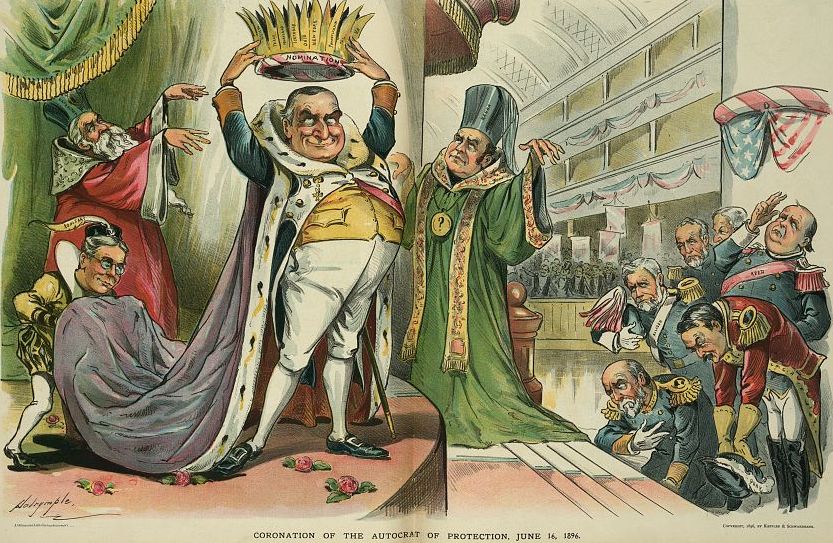

And though a lifelong protectionist on trade matters—indeed, the country's leading advocate of high tariffs—he now saw that America's thrust into the world and its growing overseas trade rendered obsolete his old philosophical commitment to "ultra-protectionism." That was what he came to Buffalo to say, in terms so muscular and eloquent that nobody could miss the full import of his conversion.

As the presidential train pulled to a stop at Terrace Station, artillerymen from nearby Fort Porter set off a twenty-one-cannon salute so thunderous that it shattered several train windows and jolted nearly everyone in the vicinity, most particularly Ida McKinley. She swooned briefly from the sudden fright. Later, as McKinley led her to a waiting carriage, she experienced a "sensory overload" as the crowd roared, bells rang out, train whistles blasted, and bands struck up martial music. The solicitous husband placed a shawl over her shoulders, ushered her into the carriage, and spread a lap robe over her legs as four handsome bays pulled the vehicle toward the fairground.

McKinley remained always attentive to every nuance of Ida's health and mood. In fact, his constant attention to her was a hallmark of his public image. The press described her routinely as an "invalid," though her condition was more complicated than that word conveyed. She suffered from a series of interconnected maladies that at times restricted her mobility and left her psychologically brittle. On this occasion she revived quickly from the disorientation caused by all the noise and "smiled happily" from the carriage window as she passed onlookers. Hardly did it seem possible from her sprightly demeanor that just a few weeks before she had been hovering near death in San Francisco, fighting off an infection that had begun with a cut finger and spread through her blood. The nation had watched in rapt alarm as she nearly died. then finally entered a slow recovery. The president remained at her side through most of the ordeal, leaving her only when his presidential duties absolutely required it. He canceled the rest of what had been planned as an extensive Western tour and postponed his scheduled Buffalo visit from June to September. Thus was he now at the Pan-American Exposition.

After touring the 350-acre fairground, with, its big red and yellow pavilions and 389-foot-high Electric Tower, the presidential entourage alighted at the nearby green-brick mansion of John Milburn, a broad faced and clean-shaven Buffalo lawyer who served as Exposition chair-man. The congenial Milburn, an English immigrant, had offered the hospitality of his home during the presidential party's Buffalo stay.

The next morning, the president and Ida left the Milburn residence at around ten, escorted by twenty mounted police and twenty members of the U.S. signal corps. They headed by carriage to the Exposition structure called the Esplanade, where they were greeted by "probably the greatest crowd ever assembled there," as the New York Times speculated. Indeed, a record attendance of nearly 116,000 people flocked to the Exposition on this day. It wasn't surprising that the president's appearance would generate this kind of excitement. Intellectuals, commentators, and editorial writers may have argued over McKinley's civic contributions or his role in the events of his presidency, but among voters the president enjoyed a hearty sentiment of approval. To ordinary Americans, he seemed solid, competent, a product of Midwestern values absorbed during his Ohio youth and while representing his Ohio district in Congress and the entire state as governor. Voters took note of his exploits during the Civil War, when he entered the army as an eighteen-year-old private and ended the war as a brevet major, most of his promotions coming after feats of battlefield valor. They liked his unadorned political rhetoric heralding traditional mores and simple verities.

As he ascended the stand and reached the speaking podium, the president pulled from his pocket a speech produced by his own hand but with substantial research assistance from his loyal and highly competent secretary, George Cortelyou. As always, however, he had solicited advice from friends and colleagues on the fine points of expression. His theme, as so often in the past, was the upward trajectory of the human experience—and the imperative of maintaining it through unfettered economic energy. Expositions helped in that regard, he said, because they were "the timekeepers of progress. They record the world's advancement." And this particular Exposition, he added, illustrated "the progress of the human family in the Western Hemisphere."

The president then moved quickly to the state of global commerce, America's role in it, and the lessons to be learned from big advances in cross-border trade. The significance of these observations extended beyond McKinley's words and concepts. Since its inception, the Republican Party, McKinley's party, had been the party of protectionism: high tariffs not just for revenue but also to protect domestic enterprise from foreign competitors. This had been the philosophy also of the Republicans' antecedent party, the Whigs, and, before them, the Federalists. Thus did high-tariff principles go back to the beginning of the Republic—indeed, all the way to its first treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. And throughout the intervening decades no politician personified this outlook more solemnly than William McKinley. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, he had shepherded through Congress in 1890 a high-tariff bill named after him. Upon becoming president, he promptly pushed through a new protectionism measure to overturn the more free-trade policies of Democratic president Grover Cleveland. But now he set out to move his party and his country in a new direction, more in keeping with America's new global position.

"Isolation is no longer possible or desirable," said the president, noting the powerful advances in the movement of goods, people, and information across wide distances. That had brought the world closer together, fostering more and more international trade. America, with its vast productive capacity, stood positioned to exploit this development like no other country. But this could happen only if Americans embraced a policy he called reciprocity: mutual trade agreements designed to reduce tariffs and enhance trade. "Reciprocity," he said, "is the natural outgrowth of our wonderful industrial development under the domestic policy now firmly established." Echoing a fundamental free-trade tenet, he added, "We must not repose in fancied security that we can forever sell everything and buy little or nothing." In other words, if the country wanted markets for its burgeoning products, it also would have to buy products from abroad. "The period of exclusiveness is past," said the president. "Reciprocity treaties are in harmony with the spirit of the times; measures of retaliation are not."

McKinley ended his speech by advocating a number of initiatives that together demonstrated a coherent view of how multiple elements of an expansionist program should be commingled. He wanted to bolster the U.S. Merchant Marine. "Next in advantage to having the thing to sell," he said, "is to have the conveyance to carry it to the buyer." He hailed the U.S. ambition to build a canal through the Central American isthmus, something he had been promoting with his usual quiet determination throughout his presidency. And he averred that the "construction of a Pacific cable cannot be longer postponed."

McKinley may not have been a man of vision in the vein of his contemporaries Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Alfred Thayer Mahan, all of whom perceived and promoted the American ascendancy long before events brought it into focus for others. But he was a man of perception who, once that focus emerged, knew how to formulate the vision and execute it. Under this concept, as applied by McKinley, America would push out on many related fronts: expanding global commerce and reducing barriers to it, augmenting naval power, controlling strategic points in the nearby Caribbean and far-off Asia, building a merchant marine, constructing and controlling an isthmian canal, enhancing cable communications around the world. As the London Standard would write of the Buffalo speech, "It is the utterance of a man who feels that he is at the head of a great nation, with vast ambitions and a new-born consciousness of strength."

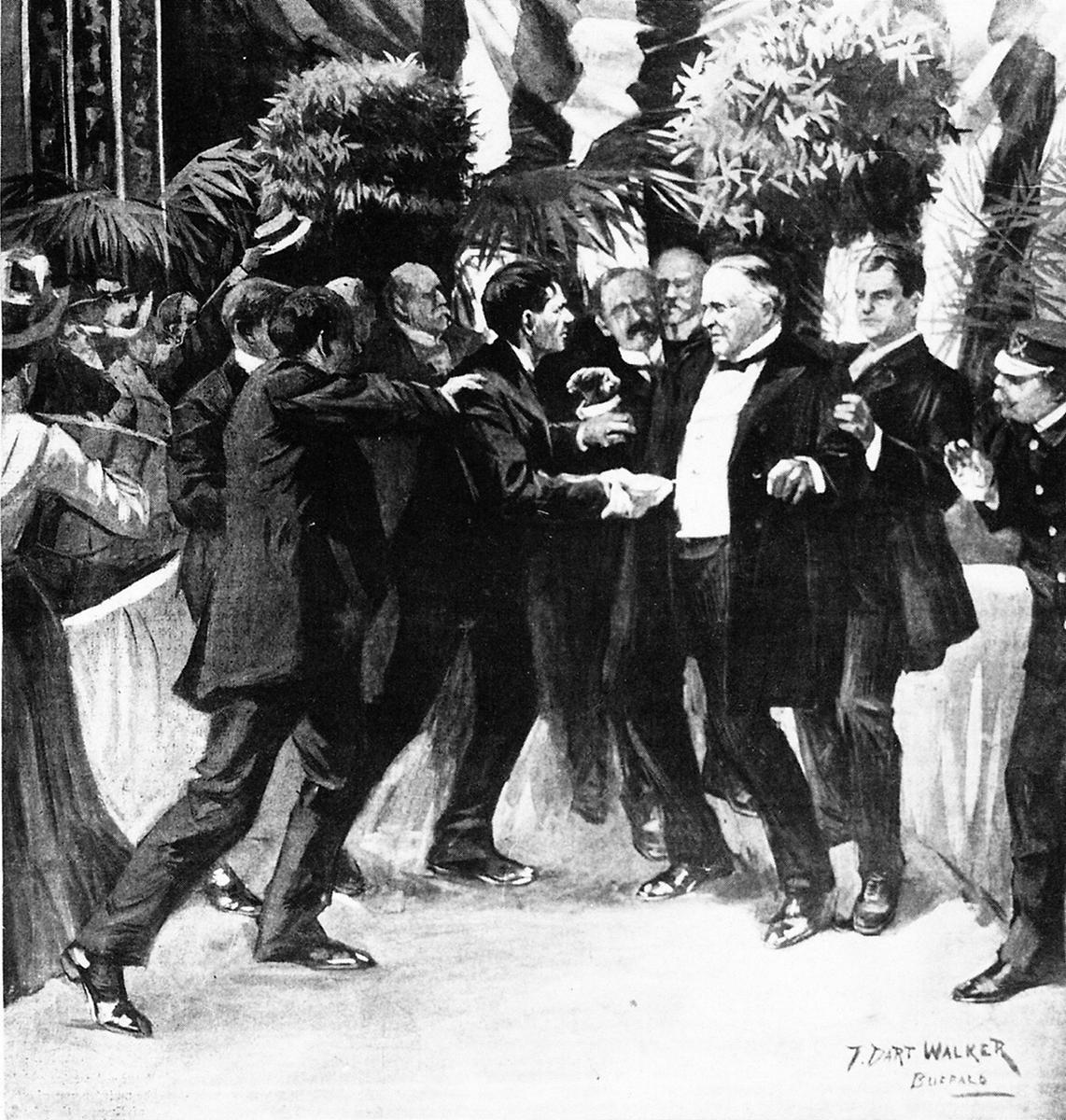

McKinley's audience responded with particularly hearty applause to his call for reciprocity treaties, his advocacy of a Central American canal and a transpacific cable, and his warm words about Pan-American cooperation. After the speech, a number of people broke through the lines surrounding the podium to gather around the president, who avidly conducted an impromptu conversation with them for some fifteen minutes. This was a Secret Service nightmare: the president in close proximity to significant numbers of people who had not been properly scrutinized beforehand. As former attorney general John Griggs explained later, "I warned him against this very thing time and time again." But the president, he added, "insisted that the American people were too intelligent and too loyal to their country to do any harm to their Chief Executive." The next morning the president would sneak past his Secret Service detail to enjoy a solitary walk along Buffalo's leafy Delaware Avenue. And he repeatedly rebuffed suggestions from Cortelyou and others that he cancel a reception-line event at the Exposition's Temple of Music the day after the trade speech "Why should I?" he responded. "No one would wish to hurt me." The president loved shaking hands with fellow citizens and developed a system of moving people along so efficiently that he could shake as many as fifty hands a minute.

Following the impromptu session with citizens, Mr. and Mrs. McKinley embarked upon a whirlwind of tightly orchestrated events and tours, including a review of U.S. troops at the Exposition stadium, a tour of horticultural exhibits, and visits to various national buildings representing such countries as Honduras, Mexico, Ecuador—and Puerto Rico, which McKinley had made a U.S. possession. The afternoon included a luncheon at the New York Pavilion, a brief rest opportunity, and then a reception at the Government Building, where the president shook hands for twenty minutes. The evening schedule included a fireworks display that occupied the president's attention until around nine. The next day's events included a boat tour below Niagara Falls and then the Temple of Music reception that Cortelyou had warned against.

Lurking in the shadows throughout the presidential visit and planning to join the receiving line at the Temple of Music was an obscure anarchist named Leon Czolgosz. While McKinley had made history through a lifetime of conscientious political toil, Czolgosz planned to make history through a single destructive act.