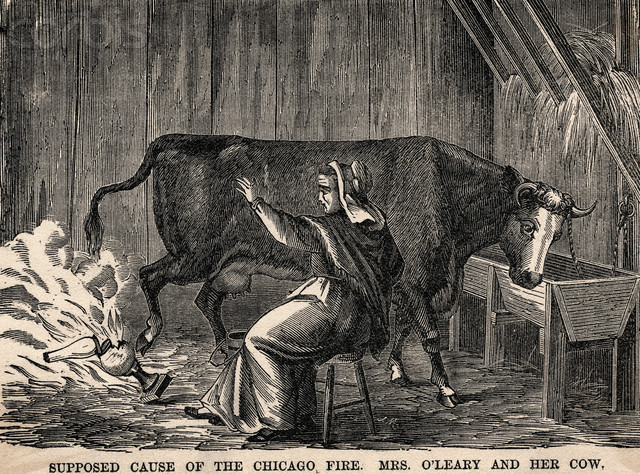

People who know nothing else about Chicago’s Great Conflagration have heard of Mrs. O’Leary and her famous cow. But the disaster's real origins are more complicated.

-

November 2020

Volume65Issue7

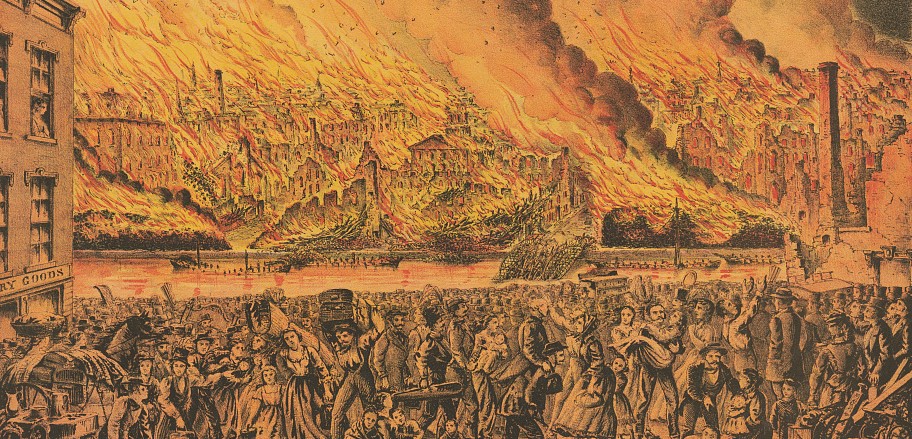

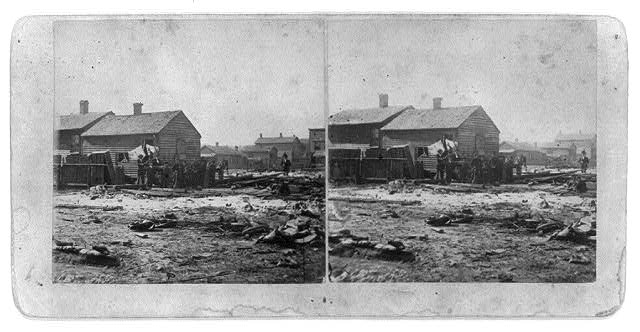

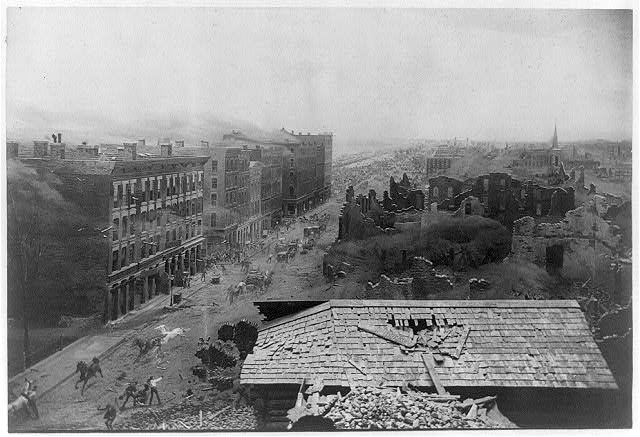

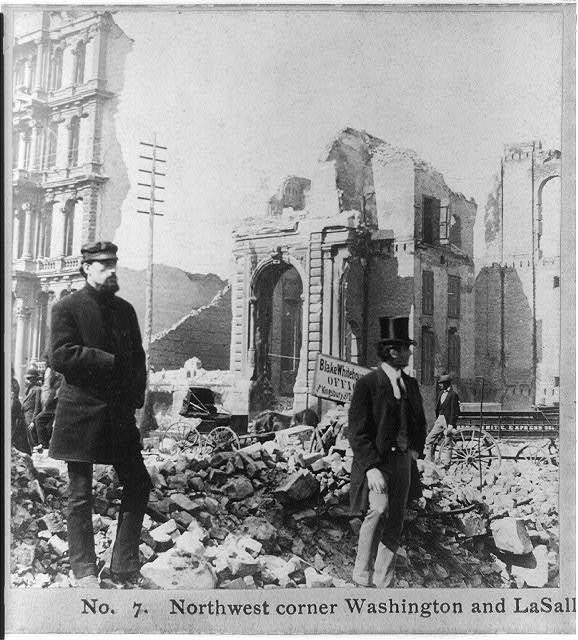

Editor’s Note: On October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed close to three square miles of the city, claimed an estimated 300 lives, and left some 90,000 homeless. Surprisingly, there has not been a major, carefully researched book on the fire until Chicago's Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City, from which this is excerpted and adapted. Author Carl Smith is a professor emeritus of English, American Studies, and History at Northwestern University.

Patrick and Catherine O’Leary lived with their five children—two girls and three boys, ranging from a fifteen-year-old to an infant—about three quarters of a mile south of the Saturday Night Fire, on the north side of DeKoven Street, some two hundred feet east of Jefferson Street. A local reporter described the neighborhood, one of the most densely populated sections of the city, as “a terra incognita to respectable Chicagoans,” packed with “one-story frame dwellings, cow-stables, corn-cribs, sheds innumerable; every wretched building within four feet of its neighbor, and everything of wood.”

Catherine O’Leary was about forty, and Patrick O’Leary a few years older. They were both immigrants from Ireland, he from County Kerry in the southwest and she from adjoining County Cork. They married before departing for America in 1845, at the onset of the potato blight that starved the country and killed or drove out more than 20 percent of the population over the next half dozen years. They had first lived in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where Patrick had enlisted to serve in the Union Army.

Patrick was an unskilled laborer, earning perhaps $1.50 to $2.00 a day when he found work. Catherine kept house and conducted a small dairy business in the neighborhood. By this time most milk arrived by train from the surrounding countryside, but it struck no one as unusual that a family, whether wealthy or poor, might keep farm animals well within the city limits. Catherine O’Leary sheltered her four cows, a calf, and the horse that pulled her milk wagon in the barn behind their home. The livestock was an important source of income in which she and Patrick had made a significant investment. She had taken delivery of two tons of timothy hay for the animals the day before. The O’Learys had also recently received and stored in the barn a supply of wood shavings and coal for cooking and to keep them warm in colder days ahead.

A person of generous inclination might call the O’Leary home a cottage, but it was not much more than a ramshackle shanty, sixteen feet wide and about twice that deep. Like thousands of others throughout the city, it consisted of a frame made of two-by-fours covered with bare pine shingles and roofed with tar paper. Houses like this were easy and inexpensive to build because of the availability of standardized milled lumber and machine-made nails. This kind of structure was well suited to circumstances where speed and economy mattered more than solidity.

The seven O’Learys shared two rooms. They enjoyed little natural light since there was only a single small window on each of their home’s four sides. The building had no foundation. Instead, wooden supports raised it a few feet above the bare ground. The rough planks that covered the gaps between these supports helped cut the wind but were hardly enough to keep the winter cold from seeping up through the floor. A stove vented with a simple brick chimney provided heat and a place to cook. Chicago streets were lit by gas, as were better offices, stores, homes, many of which also had indoor plumbing. Chicago working people like the O’Learys relied on the light of lanterns and candles, fetched water from public pumps, and used a privy.

Humble as it was, this dwelling was possibly better than what Catherine and Patrick had known in Ireland. Most important, it was theirs. Many Chicagoans even as poor as the O’Learys owned their homes, spare as those homes might be. In fact, the O’Learys owned two very similar houses, one right behind the other on their twenty-five-by-one hundred-foot lot, as well as the sixteen-by-twenty-foot back barn. The second house provided rental income. Multiple buildings jammed together like this were commonplace. The O’Learys’ current tenants were the McLaughlins, also Irish born and named Catherine and Patrick, and their toddler, Mary Ann.

Virtually all their neighbors were immigrants, mostly from Bohemia as well as Ireland. Timothy and Katie Murray lived in a cottage just to the west, James and Katie Dalton and their five children in one to the east. Murray was a carpenter, and Dalton was an unskilled laborer like Patrick O’Leary. Daniel Sullivan lived across the street with his mother. The twenty-six-year-old Sullivan earned his living driving a dray, a heavy-duty delivery wagon. A gregarious and garrulous man who favored his pipe, Sullivan was an easily recognizable figure on DeKoven Street since he hobbled about on a wooden leg.

The O’Learys turned in about the same time as Chief Fire Marshal Williams. Catherine, who was nursing a sore foot, would have to awaken a little after 4:00 a.m. to milk her cows. Daniel Sullivan came by to chat the O’Learys up, but he left when he discovered they had already gone to bed. As Catherine and Patrick dropped off to sleep, they could hear through the wall quadrilles rising from Patrick McLaughlin’s fiddle, to which guests danced in a welcome celebration for a relative just arrived in America.

An hour later, about nine o’clock, Daniel Sullivan’s urgent shouting roused Patrick. O’Leary jumped out of bed, opened the door, and looked to the rear of the lot.

“Kate!” Patrick screamed to his wife, “the barn is afire!”

An Ideal Suspect

The Chicago Evening Journal, the only local newspaper to publish on Monday, October 9, reported that the fire began with “a cow kicking over a lamp in a stable in which a woman was milking.” Since then this story and the fire have been inseparable. People who know nothing else about the Great Chicago Fire have heard of Mrs. O’Leary and her cow.

The spectacular conflagration that struck Chicago on the evening of Sunday, October 8, 1871, is the most well-known urban fire in the history of the United States and one of the nation's most fabled disasters. The flames that started in the West Side barn where Catherine O'Leary tended her milk cows devastated close to three square miles of cityscape, including the heart of the city's kinetic downtown, and left around ninety thousand people homeless. The relentless fire did not cease until it burned itself out in the early morning of Tuesday, October 10, some thirty hours after it began.

The Great Chicago Fire has had a powerful and enduring imaginative resonance. It immediately drew enormous attention, including a spontaneous outpouring of millions of dollars in charitable contributions from around the nation and the globe. This was because Chicago, which barely existed only forty years earlier, had already assumed a commanding position in the urbanizing and industrializing world's widening transportation and communications network. In its insatiable ferocity and preternatural vigor, the fire was a fitting counterpart to this epic new city.

But the fire also made clear how flammable the city was socially as well as physically. Chicago was undeniably a distinctively American urban success story, a gathering of a vast and ever increasing number of people of very different backgrounds and outlooks who joined together to accomplish great things. But inherent in the formation of this sudden city of so many individuals from so many places were sharp economic, ethnic, political, and religious differences.

The multiple crises and challenges posed by the fire brought these differences fully out into the open.

Several factors made Catherine O’Leary a convenient person on whom to pin the blame. Eyewitnesses located the first flames as flaring from the barn where she attended her cows. There was considerable comfort in tracing the origin to a specific cause, as opposed to not knowing how and why the fire began. Attributing it to an accident was much less disturbing than believing that a person or persons, with or without a specific motive, purposely set Chicago afire. Tying the enormous destruction to a humble source also offered a certain ironic satisfaction, and a suggestive precedent lay in one of the few comparably large urban conflagrations. The London Fire that began on Sunday, September 2, 1666, originated in baker Thomas Farriner’s kitchen on Pudding Lane.

Catherine O’Leary already had at least five strikes against her: she was a poor immigrant Irish Catholic woman. In this very unsettling moment, she provided a place for settled opinions—xenophobic, anti-Irish, anti-Catholic, and sexist prejudices—to find confirmation. She was also defenseless and illiterate, with no effective means to counter her accusers.

Other theories about the fire’s origins surfaced at the time in the newspapers, most of them placing a similar person in or near the barn when the blaze broke loose. Some suggested that the McLaughlins, the tenants in the O’Learys’ front cottage, or one of their guests that evening had ventured into the dark barn to draw fresh milk for a celebratory punch. Others speculated that the fateful spark came from the pipe of Daniel Sullivan, the one-legged neighbor who awakened Patrick and Catherine O’Leary, or that boys shooting dice or playing cards in the barn ignited the hay. Perhaps it was a wayward cinder from someone’s chimney. Maybe spontaneous combustion. Or an arsonist who just liked to see things burn. Or those Communards or other sinister enemies of the established order.

None of these alternatives could budge Catherine O’Leary from her unenviable position as prime suspect. Reduced to a caricature whom unsympathetic and even hostile journalists could shape any way they pleased, especially since there were no photographs or accurate likenesses of her, she remained guilty in the court of public opinion. The fact that the fire spared the O’Leary home while destroying others all around it reinforced the idea that she was blameworthy.

While most accounts depicted her as too ignorant and inept to have committed the act intentionally, some reporters suggested otherwise. In its first postfire issue, the Chicago Times vilified the hardworking O’Leary, who was not on any dole, as a welfare fraud who, when cut from the rolls, swore that “she would be revenged on charity that would deny her a bit of wood or a pound of bacon.” The paper likened her to “any one of the vermin which haunt our streets.” While she was actually around forty, the Times described her as a bent-over crone of seventy.

For a few days after the fire the O’Leary neighborhood was a circus. A photographer led a cow (some say a bull) next to their home and snapped a picture. Illustrators, none of whom ever laid eyes on Catherine O’Leary, joined the Times in aging her by decades. They depicted her looking on with shock and dismay, or as comically falling backward head over heels and skirts in the air, as the lamp goes flying.

To the mainstream daily English-language press, the O’Learys and their world were so alien to respectable sensibilities that reporters described the investigations of their neighborhood as a journey into the primitive unknown. In March 1871, about six months before the Great Chicago Fire, the New York Herald had sent Henry Morton Stanley to deepest Africa in search of long-lost British explorer Dr. David Livingstone. When he found the object of his quest by the shores of Lake Tanganyika in early November, Stanley famously asked, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

By that time the New-York Tribune had put John Hay on a train to Chicago to report on the fire. “Curious to see the first footprint of the monster who had trampled a great city out of existence in a day,” Hay set forth across the Twelfth Street Bridge and into the O’Leary neighborhood, a place “wholly foreign and not quite reputable.” Hay’s account, which was reprinted in the Chicago papers, was a reprehensible exercise in condescension and disdain, as vicious in intent as it was elegantly written. On his way to interview Mrs. O’Leary, Hay explained, he first encountered German relief volunteers guarding supplies from hungry Czechs who communicated with each other in broken English, which made him fear for “the final doom of our language.”

Hay called the block where the O’Learys lived “a mean little street of shabby wooden houses, with dirty dooryards and unpainted fences falling to decay.” It did not seem to belong in this city of vitality and enterprise. As he put it, “It had no look of Chicago about it.”

At last he reached the “the squalid little hovel” he dubbed “the Mecca of my pilgrimage.” Hay beheld “a warped and weather-beaten shanty of two rooms, perched on thin piles, with the plates nailed half way down them like dirty pantalets. There was no shabbier hut in Chicago nor in Tipperary.” Adapting the story of Chicago’s tale of destruction to the framework of the nursery rhyme “The House that Jack Built,” Hay wrote of the O’Leary home, “For out of that house, last Sunday night, came a woman with a lamp to the barn behind the house, to milk the cow with the crumpled temper, that kicked the lamp, that spilled the kerosene, that fired the straw, that burned Chicago.” To which he added, with a flourish of personification, “And there to this hour stands that craven little house, holding on tightly to its miserable existence.”

Hay claimed that he interviewed Patrick O’Leary, who greeted him with “sleepy, furtive eyes” and whom Hay belittled by using capital letters to refer to him as “the Man of the House.” When O’Leary said he had nothing to do with starting the fire, Hay felt that “there was something unutterably grotesque in this ultimate atom” discussing his possible relation to “a catastrophe so stupendous.” Hay aimed his most elevated sarcasm at Catherine O’Leary, with whom he did not deign to speak: “Our Lady of the Lamp—freighted with heavier disaster than which Psyche carried to the bed-side of Eros—sat at the window, knitting.”

In the few apparently legitimate interviews Catherine O’Leary did grant immediately after the fire, she repeatedly said that she was asleep when it began, and Daniel Sullivan had awakened her by rapping on the door. She explained that her house was saved thanks to the many friends who threw water on its walls and roof. While the reporters did not seem to notice, she thus described her neighborhood as a community, not Hay’s forlorn wasteland of pathetic outcasts.

A fellow Irish Catholic immigrant named Michael McDermott tried to assist the O’Learys in presenting their side of the story. Unlike them, he was an educated professional, a civil engineer and surveyor. On October 15 McDermott took sworn affidavits from the couple and Sullivan that soon appeared in the Chicago Tribune. In her statement Catherine O’Leary said that she milked her cows daily at 5:00 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. On the evening of the fire, she made her last trip to the barn at about seven o’clock, when she fed the horse and put him in for the night. She carried no lamp. Patrick O’Leary attested that he had nothing to do with the animals, which his wife and oldest child, fifteen-year-old Mary, fed and milked. The family was in bed when the fire started.

The couple pointed out that they, too, were its victims. It had cost them their barn and livestock, on which they had no insurance. In his affidavit, Daniel Sullivan stated that he had called on the family between eight thirty and nine o’clock but left as soon as he discovered they had gone to sleep. He spotted the fire from across DeKoven Street a short time later. He had tried to save the animals but the only one he could rescue was the calf. All three signed their statements with an X.

McDermott sent a note to the Tribune along with the affidavits. “A great deal has been published respecting the origin of the great fire,” he wrote, “which all reports have settled down on the head of a woman, or as the Times has it, an ‘Irish hag’ of 70 years of age.” Even if the O’Learys had in fact been blameworthy, “there was a great want of charity in the epithets used by the Times.” But in fact they were innocent. “The following facts [i.e., the accounts in the affidavits] are stubborn things, and will cause the public to look for the cause in other sources, and perhaps attribute it to the love of plunder, Divine wrath, etc.”

Crime and Punishment

We cannot be sure just what McDermott meant by his reference to “Divine wrath,” but many Americans understood experience generally and cataclysmic events in particular through a conceptual framework of sin and punishment. Shortly after the fire, a few clergymen interpreted Chicago’s suffering as a straightforward example of Old Testament–style justice. The Reverend Edgar J. Goodspeed of the Second Baptist Church, author of those successively longer fire histories, read the disaster as God’s response to the city’s violations of the Sabbath, its drinking and materialism, and its profusion of theaters, brothels, and “gambling-hells.”

Granville Moody, a Methodist minister in Cincinnati, concurred. Moody was an unusually militant person. He joined the Union Army not as a chaplain but as commander of the Seventy-Fourth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, attaining the rank of brevet brigadier general. Afterward he returned to the pulpit with the imprint of the battlefield still on him. He viewed urban life as a constant clash between the armies of righteousness and evil. The fire was “a retributive judgment on a city which has shown such a devotion in its worship to the Golden Calf.”

Even Mayor Roswell B. Mason nodded to this view in a proclamation that set aside Sunday, October 29, as “a special day of humiliation and prayer” in acknowledgment of “those past offenses against Almighty God, to which these severe afflictions were intended to lead our minds.”

Other believers preferred to envision the fire as the work of a loving God who, in spite of all the destruction, cared deeply for humankind. The most prominent spokesman for this outlook was the best known clergy man in the country, Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher. Based in the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, the fifty-eight-year-old Beecher spread his ideas nationally on the lecture circuit and in newspapers, magazines, and books.

Beecher was the younger brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the extraordinarily popular 1852 novel credited with widening opposition to slavery and hastening the Civil War. Their late father Lyman Beecher had been another noted man of the cloth. Henry agreed with some of Lyman’s views, such as his father’s championing of temperance, but he saw God as far more compassionate.

Like many other ministers across the country, Beecher devoted his sermon the Sunday after the fire to the inferno that was the talk of the nation. Beecher took as his text “Thy judgments are a great deep,” from Psalm 36. He began by acknowledging that events like the fire raise the question of why God causes terrible things to happen that inflict as much pain on the upright as on the wicked. Beecher advised against expecting an answer to theological conundrums like this. “If you pursue them,” he warned, “that way lies atheism.”

Beecher did not concern himself with the story of the O’Learys, the cow, the broken lamp, or any other proximate cause of the fire. To him the most interesting aspect of the entire experience was what it revealed about one of the great issues of the day, urbanization, bundling under this heading the modern forms of communication on which the nation increasingly relied.

“This great national disaster is a revelation of the structure and function of cities in the organization of society,” he asserted. One could see this most clearly in the gloriously generous reaction to Chicago’s misfortune, a sign that so many people felt it personally. The wholehearted way humankind at large reacted to Chicago’s blow indicated that “a city is, for the time being, the point where God enthrones himself in wisdom and power.” No person could be a good citizen, patriot, or Christian who did not care about what happened in places like Chicago, on which every business’s prosperity and each family’s well-being depended.

Beecher urged his listeners and readers to embrace all the affirmative aspects of the fire. He admitted that there was nothing as hideous as the reports of crime, looting, and debauchery, but he noted how few such stories were in comparison to those of bravery and selflessness. Most wonderful of all was the current rush of support from around the country to the fallen city, overflowing as it was with “moral riches” as well as material ones.

Far from a visitation by an angry God, the fire was “a great national blessing” that demonstrated the triumph of selfless Christian love. The tragedy that leveled Chicago broke down existing divisions—from doctrinal differences between religious denominations to lingering bad feeling between Britain and the United States attributable to the former mother country’s support of the Confederacy—by reminding us of the sympathy all feel for suffering humanity. “We are richer to-day with Chicago burned, than we were last month with Chicago unburned,” Beecher declared, leading into a resounding double negative: “We could not have afforded not to have had her burned.”

In closing, Beecher looked his congregants in the eye and asked them directly for donations. A note to a published version of the sermon states they responded with $5,000 in pledges.

Excerpted from CHICAGO’S GREAT FIRE © 2020 by Carl Smith. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved