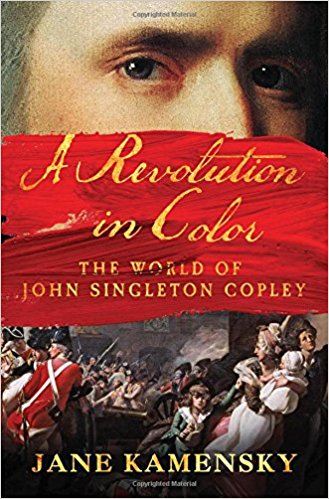

To explore the American Revolution through the eyes of John Singleton Copley is to see it with fresh eyes, to understand that it was a civil war with many shades of allegiance.

-

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017

Volume62Issue4

When you walk through the heavy glass doors of the Americas wing in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, you come face to face with the men and women who made the American Revolution. Paul Revere greets you, head on, just inside the entrance. His iconic likeness—unwigged, shirtsleeved, silver teapot in hand—hangs low enough that his big brown cow eyes meet yours with neither modesty nor condescension. Revere’s is the honest, direct gaze of an honest, direct man: an American gaze. Vitrines holding examples of the silversmith’s craft surround the portrait of the self-made maker. His famous Liberty Bowl stands on a platform just in front of it, like a chalice proffered by a preacher. In the 1950s, the churchiness of the presentation was franker; the portrait and the bowl were placed upon a pedestal with a couple of steps before it, suitable for genuflecting, flanked by American and Massachusetts flags. But even today, in a new and less earnest century, Paul Revere forms the center panel of an American altarpiece.

Behind Revere, on the left, hang a quartet of his fellow revolutionaries. John Hancock, the stalwart merchant, sits at his desk, reckoning, the quill that will ink his bold signature on the Declaration of Independence poised in his right hand. Samuel Adams—the maltster’s son turned politician—stands in a homespun crimson suit, drawn up to his full, modest height, eyes alight with patriotic zeal. Dr. Joseph Warren, the physician, pores over a set of anatomical drawings that seem to prefigure his death and resurrection as the martyr of Bunker Hill. Mercy Otis Warren, the sister of one liberty man and the wife of another, appears lost in thought as she stands before a burbling fountain, displaying the contemplative bent of the intellectual who will write the Revolution’s first major history. the portraits were painted separately, in the 1760s and early 1770s, tumultuous years in the world beyond their gilded frames. they were meant for separate fates, in firelit parlors in middling homes, in a bustling entrepôt at the edge of an empire. Viewed together centuries later, in the chilly splendor of a great museum, through the glaring light of hindsight, they become a patriotic pantheon: American originals, painted by another of their breed. the labels identify the artist as the MFA owns the largest collection of Copley’s work in the world: scores of paintings spread across four galleries and myriad works on paper tucked away in the department of prints and drawings, where they can be viewed by appointment, under low light. But though Copley’s legacy is more vivid in Boston than in most other places, just about any major museum in the United States will tell you a version of the same story. At the Met in New York or the Art Institute of Chicago, at the National Gallery in Washington or the De Young Museum in San Francisco, in Detroit and Toledo and Lawrence, Kansas, and Crystal Bridges, Arkansas, and on around the vast continental nation that Copley never imagined, his work is classed as American art, with labels that add greater and lesser degrees of mystery: “American, active in Britain,” “American, died in London.” Whatever the label, Copley’s brush is pressed into much the same service: a conjurer’s work, creating our mind’s eye picture of the nascent American republic, of which he emerges, on those walls, as court painter.

Nothing would have surprised Copley more.

A cautious man in a rash age, John Singleton Copley feared the onrush of the colonial rebellion against Great Britain. Like many people of his place and time, he called the rebels’ revolution a civil war. And like many people who had lived through civil wars before him, and who have endured them since, he thought the safest side was no side at all. Copley painted John Hancock, whom he knew well and grew to despise. But by the time Hancock signed the Declaration, the painter was long gone from the country that document called into being. In the spring of 1774, during the brief interval between Boston’s “tea party” and the outbreak of fighting in Lexington and Concord, Copley sailed to London, capital of the only nation he had ever known, leaving behind the second-tier British port city in which he had spent nearly four decades. John Singleton Copley had lived half his life in Britain’s American provinces. He would never set foot in the United States.

British museums, which own the greatest of his works, classify him differently. “John Singleton Copley, R.A. . . . British School,” runs the text inscribed on the frame of The Death of Major Peirson, my very favorite of all his paintings, which hangs in the Tate, hard by the Thames. The heroic canvas depicts a passage in Britain’s American War that falls outside the standard narrative of the American Revolution: a battle that took place in an obscure corner of Europe, that featured no North American combatants, and that ended in British victory.

To explore Copley’s American Revolution is to treat that war, and its world, with fresh eyes. In the United States, where the War of Independence functions as a national origins story—a “founding”—we tend toward histories peopled by Patriots and Tories, victors and villains, right and wrong. Such tales, for all their drama, are ultimately flat: morality plays etched in black and white, as if by engravers who have only ink and paper to depict all the shades of a subject. But like the paintings Copley produced so painstakingly, the revolutionary world was awash in an almost infinite spectrum of color. Allegiance came in many shades. Some pigments were durable, others fugitive and shifting. The age of revolutions takes on a prismatic quality when we try to view it through Copley’s slate-colored eyes, eyes that saw deeply, and revealed many truths, not all of which we now hold to be self-evident.

The title of my book also refers to Copley’s work, which began, in his tender years, as a trade. As he grew in both mastery and drive, it became a calling. As a painter of portraits and, once he escaped the confines of Boston, of the more elevated genres of history, religious art, and classical allegory, Copley worked in the upper echelons of the color trades, which included everyone from the farmers who grew the madder root from which the day’s most popular bricky reds were made, to the collectors of burnt ivory that produced the richest blacks, to the merchants who trafficked in powdered pigments from around the globe and the shopkeepers who sold them at retail, to the many kinds of painters who worked with those stuffs: housepainters and sign painters and clock painters and wallpaper screeners, and on up the ladder of occupations to the painters of landscapes, human faces, and the higher reaches of Art.

A preposterously ambitious poor boy from a preposterously ambitious place, Copley glimpsed that ladder early and climbed it relentlessly— never resting, never satisfied—for seven decades, on two continents, through four global wars. His life in color is a story of striving, a species of ambition seen, even then, as peculiarly American: hard-edged, uncloaked, impolite. Like many stories of striving, Copley’s is also a story of ever-increasing scale, both on and off the canvas. Boston was a place to paint small, to paint faces: art destined to hang in little clapboard houses, pictures that spoke to families. Paul Revere is a bit more than two feet wide, and a hair less than three feet high. In London, Copley’s compass grew, and with it his works. The pictures got big, many times the size of Revere. His largest and most complex paintings—sometimes, though not always, his best—were meant to rivet exhibition-goers, to hold a palace wall, to fill a tent.

But unlike so many rags-to-riches tales of American ambition—a genre that began to circulate toward the end of Copley’s life and that dominates our national imagination still—Copley’s is a story of profound and crippling disappointment, agonies born of both self and circumstance. His was a rueful revolution, long on second guesses and short on second chances. Though his work could be daring and innovative, he was a man of indecision, a character that might have sat more easily in an era less consumed with the urgency of choosing one’s destiny. The age of revolutions was an urgently forward-facing moment. Copley, by contrast, had what the people of his day called a bivious gaze, forever alternating between glancing over his shoulder and peering at what was ahead of him. It was a painful way to be in a go-ahead world, though by no means a singular one.

Copley’s bivious vision endures because he worked as a visual intellectual. His life and work invite us to see the age of revolutions in all its myriad complexity. Visual metaphors were central to Copley’s way of imagining and organizing his complex world. He wrestled with the tensions between figure and field, the portrait and the crowd, the modern and the antique. He was often accused of paying too much attention to details at the margins of a scene, finishing all parts of a picture equally and thus making it “difficult for a beholder to guess which object the painter meant to make his main subject,” as one reviewer in London noted in 1777. When the background got too vivid, the story grew muddy. Deemed an artistic failing, Copley’s tendency to dwell on and in the verges is also a gift, drawing our attention to overlooked aspects of a story too often cast in spotlight and shadow.

Background matters to the story of Copley’s revolution, which centered less on the struggle of rebel colonists against the British crown than on family politics, the labor of art, and the dark undersides of liberty, including chattel slavery, which Copley both practiced and theorized. The history that becomes visible through his eyes is no easy story of the progress of America, but rather a stuttering series of rises and falls and eddies, all worked out on canvas, in a palette that remains startlingly fresh.

That vividness is one reason painters are good to think with. But there are others, too. Like most who practiced his trade, Copley was a middling man. He shows us those above him on the ladder of hierarchy in their true colors. He also looks, often anxiously, at the echelons of society below, which he narrowly escaped, through a combination of gumption and good luck. He remained, all his life, obsessed with rising above and afraid of falling back, properties visible in many of his works, and in the unusually large corpus of letters he left behind. A strenuous autodidact, Copley had gorgeous penmanship and terrible spelling. His letters are full of self-searching, a degree of introspection that may be common to most Homo sapiens, but is seldom accessible to historians who study people of lower middling status. Copley’s correspondence offers a rare glimpse of the development of an artist’s sight and insight, as well as a history of the early American eye.

And then, of course, there are the pictures, hundreds of them, painted on both sides of the ocean that defined the outer limits of his imagination. On the page and on canvas, Copley worked out his life in plain sight, in ways that, almost miraculously, remain visible still, some two centuries after his death.

A canvas by Copley hangs in my office, on loan from my university’s art museum. It’s an early portrait, painted ca. 1759–60, when the painter was just twenty-one or twenty-two years old. The sitter, Miss Dorothy Murray, was younger still, fifteen or sixteen when she sat for her picture. The painting is a frozen moment from a vanished time: a glimpse of some morning or early afternoon—most of the year, the light wasn’t strong enough after that—on which two young people came together in a sunlit room, on the second story of the house Copley had recently purchased on Boston’s Cambridge Street, where he lived with his fragile mother and his much younger half-brother, Harry. For some years already, he had been the family’s sole support, painting for his life. they were, both of them, painter and sitter, quite ordinary folks: the Scottish merchant’s daughter, the Irish tobacco seller’s son, aspiring, together, through the extraordinary act of portraiture.

It is not an exceptional portrait; indeed, but for the subsequent fame of its painter, it is not really even a museum-quality work. Copley cannot quite manage the arms yet, much less the hands. The disposition of the body in space remains a mystery to him. Dorothy Murray wasn’t especially well fabricated and hasn’t, over the years, been especially well tended. It has lost a lot of paint. the figure is wooden, the brushwork halting, the overall effect somewhat folky, or “primitive.” In all these ways, it could pass for an unusually fine work by some itinerant hack—by Joseph Badger, maybe. But oh, that face! Fresh as youth, fresh as yesterday: a woman on the verge.

Living with it as closely as it was meant to be lived with, daily, without stanchions or guards, without companions or a wall label, I have come to see a special poignancy in the canvas, which is perched in every way on the precipice of becoming—the young lady blooming, the painter’s talent unfurling, the Seven Years’ War soon to end in a total, unexpected victory that would prove both exhilarating and cataclysmic for Britain’s empire. The collision of all of these things is ineffable, and unique. There is nothing scientific, even social scientific, about such encounters. the experiment cannot be repeated to test the results.

A biography is in many ways like a portrait. the genre traffics in the individual, the irreproducible, the extraordinary. Had Copley not burst the frame of his times by painting what and how he did, and especially when he did, it is unlikely that the material would have survived to allow me to tell his story—and unlikelier still that you would want to read it. A hundred ordinary people, armed with a hundred paintbrushes, toiling for a hundred years, would be hard pressed to paint something half so transcendent as Dorothy Murray, let alone Paul Revere or The Death of Major Peirson.

And yet, much as Copley made a world with his brush, his place and times also made him. Most people of the day were, as he was, creatures of kin and community, homemade and marriage-made more than self-made. Family ties mattered at least as much as political allegiances. And like Copley, most “Americans” were both military and ideological noncombatants when the war came. In a polygonal conflict that was at once a struggle for colonial independence, for native territorial sovereignty, for British imperial coherence, for European hegemony, for African American freedom, and much more, many deemed it best to do what Copley urged Harry: to forswear arms and pledges, to keep his own counsel, to wait and see how it all came out. the American Revolution looks different seen through his eyes, looking west from London: a sidelong glance at a sideways war, the conflict that made and unmade him. the closer we get to such ambivalent characters—both the ones in Copley’s own household and the ones he painted—the more our easy verities about the period dissolve.

American historians of the American Revolution, no less than the rest of our fellow nationals, tend to believe fervently in the notion of choice, liberalism’s first commandment. Colonials chose sides; some chose right and others chose wrong. But as Copley saw it, the sides—of the war, of the ocean—chose him. To recover such stories, in all their vexing multiplicity, is to contemplate a different American war, and maybe a different America as well.

Copyright © 2016 by Jane Kamensky.