AN ANNIVERSARY LOOK BACK AT THE BIGGEST PRESIDENTIAL SCANDAL EVER, THROUGH THE CHANGES IT WROUGHT IN THE LANGUAGE

-

October 1997

Volume48Issue6

“I will repeat again today that no one presently employed at the White House had any involvement, awareness or association with the Watergate case.” Just twenty-five years ago this month, with national elections less than three weeks away, President Richard M. Nixon’s press secretary, Ronald L. Ziegler, sought with this declaration to clamp the lid on a burgeoning scandal.

Ziegler’s statement is a classic example of Watergate-ese. By saying “presently employed,” he carefully distanced the White House from the event that gave the scandal its name—a break-in on June 17, 1972, at the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in Washington’s Watergate complex. When reporters pressed on with questions about a recently revealed Republican campaign to disrupt Democratic primaries, Ziegler replied that “no one in the White House at any time directed activities of sabotage, spying, [or] espionage.” Here the key word was “directed.” The press secretary determinedly avoided “involved in.” Finally, all fine points of semantics aside, Ziegler’s statements were—as he himself was forced to concede six months later—not true anyway.

In the short run, though, Ziegler’s denials held up. The President’s popularity was cresting at the time. On November 7 Nixon was reelected in a landslide, receiving more than 60 percent of the popular vote, a near-record, and winning forty-nine of the states. It would be almost two years before he resigned in disgrace.

No one who was old enough to read newspapers or watch television will ever forget the events of this period, and in no small part because of the language associated with them— artfully devious in public, remarkably blunt and vivid in private. Cancer on the Presidency, deep-six, enemies list, executive privilege, expletive deleted, inoperative, Saturday-night massacre, smoking gun . These are among the Watergate words that are now ingrained in the American language, probably forever, thus sure to help the scandal endure in the popular imagination.

Here, to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the break-in, is a glossary of some of the words of Watergate. Together they tell much of a complex and endlessly fascinating tale.

Meaning: Now (or then).

John W. Dean III, who as counsel to President Nixon was intimately involved in the conspiracy to cover up responsibility for the break-in at the DNC offices, used “at this point in time” and “at that point in time” repeatedly when he appeared as a star witness in the last week of June 1973 at the televised hearings of the special Senate committee investigating the Watergate affair. In the public mind the phrases summed up the tenor of his testimony, much as “point of order” characterized the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954.

The expressions are standard bureaucratese: Never use one word where five will do. Recalling, not so fondly, his dealings with the State Department in the Kennedy years, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., notes in A Thousand Days that the men in that department “never said ‘at this point’ but always ‘at this point in time.’” Dean’s employment of the stock phrase inspired much merriment, but it is a useful device for someone undergoing cross-examination. It gives the witness time to think ahead and frame the substance of a reply.

Dean’s testimony to the senators and at the 1974 trial of the chief conspirators (excepting the President) did not get him totally off the hook. He was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice and sentenced to one to four years in prison. After four months, however, the Watergate trial judge, John J. Sirica, reduced his sentence to time served.

Meaning: Contradicts.

President Nixon was a master of the shameless understatement, exemplified by the reason he gave on August 8, 1974, for deciding to resign: “I no longer have a strong enough political base in Congress.” This, after the House Judiciary Committee had voted 27-11 to impeach him and after Senate Republican leaders had told him that he might get no more than 15 of the 34 votes he would need in that house to stave off impeachment.

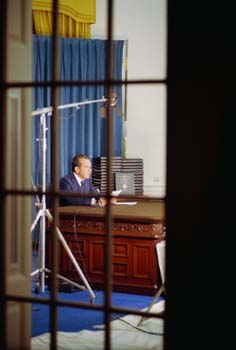

Nixon floated "at variance with" on August 5, 1974, soon after the United States Supreme Court ruled (see executive privilege) that he had to surrender the tapes of sixty-four secretly recorded meetings, which had been subpoenaed by the special Watergate prosecutor. When releasing transcripts of these tapes, Nixon noted that portions of three conversations on June 23, 1972, which he had in the Oval Office with his chief of staff, H. R. (“Bob”) Haldeman, were “at variance with certain of my previous statements.”

In fact, the transcripts showed that the President had lied repeatedly. He had denied knowing anything about the conspiracy to hide responsibility for the third-rate burglary (see below) at Watergate until nine months after it took place, when John Dean told him that the cover-up had become a cancer on the Presidency. Now the tapes revealed that he had been told about the plot to obstruct justice just six days after the event. Moreover, he had participated actively in it.

At the time of Nixon’s June 23 conversations with Haldeman, the FBI was starting to follow a money trail. About twenty-three hundred dollars, mostly in sequential hundred-dollar bills, had been found on the five men arrested in the DNC offices; more packets of bills were discovered in their hotel rooms. Knowing that the trail led to two Republican-party contributors, and from them to the President’s re-election campaign committee, Haldeman proposed—and Nixon immediately agreed—that the CIA be asked to tell the FBI not to interview the donors. The ruse seemed plausible because the White House consultant E. Howard Hunt, Jr., who had helped plan and oversee the break-in, was a former CIA agent. (Hunt was not arrested on the scene, but his name and telephone number appeared in address books carried by two of the burglars, together with the notations “W.H.” and “W. House.” Moreover—truly great spycraft!—an unmailed check by him for his country-club dues was found in one of their hotel rooms.)

Said the President to his chief of staff: “You call them [the CIA director, Richard M. Helms, and his deputy, Lt. Gen. Vernon A. Walters] in. … Play it tough. That’s the way they play it and that’s the way we are going to play it. … Say: ‘Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing. … and that they should call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case, ’‘period!”

The ploy did not work. Two weeks later a nervous L. Patrick Gray III, acting director of the FBI, following J. Edgar Hoover’s death in May, asked the CIA to put its request not to interview the Republican contributors into writing. Walters not only declined to do so but wrote a memo saying that further investigation could not damage the agency because it had had no involvement in the break-in.

Revelation of the June 23 transcripts led almost immediately to Nixon’s resignation. These meetings constituted the smoking gun. (If the President had been involved in the cover-up even earlier, that evidence was lost in the gap.) Nixon was later pardoned by his successor; see mistakes and misjudgments. Haldeman served eighteen months in federal prison.

John F. Ehrlichman, President Nixon’s chief domestic affairs adviser, produced this spicy characterization of Mitchell during a conversation with Haldeman and Nixon on March 27, 1973. The brunt of the discussion was how to get Mitchell to take the rap (“to come forward,” as Ehrlichman later put it) for the Watergate break-in. Mitchell was an obvious fall guy. The re-election committee’s security coordinator, James W. McCord, Jr., was one of the five men arrested in the DNC offices (the other four were Miamians with ties to the CIA and anti-Castro groups); the committee’s counsel, G. Gordon Liddy, was the chief planner of the break-in; and committee money had financed the operation (see launder). The hope of the White House conspirators was that prosecutors would be so pleased by snaring Mitchell that they would proceed no further—in other words, that the wolves would be thrown off the scent by the big enchilada.

Haldeman: “He is as high up as they’ve got.” Ehrlichman: “He’s the big enchilada.” Ehrlichman did eighteen months in prison for various Watergate-related crimes; Mitchell, nineteen.

Meaning: The conspiracy to cover up responsibility for the Watergate break-in and other criminal activities.

When John Dean, who was only thirty-four at that point in time, testified before the Senate Watergate committee on June 25, 1973, he was pitting his word against that of the President of the United States. When ten months later, on April 30, 1974, more than twelve hundred pages of White House transcripts were released, Dean’s testimony suddenly seemed much more credible. According to the record of his conversation with the President on the morning of March 21, 1973 (the meeting in which Nixon claimed falsely to have learned for the first time of the cover-up), Dean had warned, “We have a cancer—within—close to the Presidency, that’s growing. It’s growing daily.”

The “cancer” was growing because more people had to perjure themselves as the Watergate investigation widened and because of the demands of E. Howard Hunt for hush money (or “humanitarian relief”). By March 1973 the Watergate burglars had extracted more than two hundred thousand dollars from the Nixon campaign organization for bail money, living expenses, and lawyers’ fees. The payments had helped maintain the fabric of the cover-up. Despite sharp questioning by Judge Sirica, who clearly didn’t believe that the men were acting on their own, the trial of the Watergate burglars had ended on January 30 without implicating any higher-ups. (Liddy and McCord were convicted; Hunt and the four Miamians pleaded guilty.)

Now Hunt was demanding another $122,000 for personal expenses and legal bills. Unless he got it, Dean told the President, Hunt threatened to “bring John Ehrlichman down to his knees and put him in jail” by exposing all the “seamy things” he had done for Ehrlichman. Dean could see no end to the extortion. He told Nixon that the cost of keeping Hunt and the others quiet might amount to a million dollars over the next two years—and that he didn’t know where to get the money. But the President assured him: “You could get a million dollars. And you could get it in cash. I, I know where it could be gotten. … It’s not easy, but it could be done.” Nixon went on to say that “the Hunt problem … ought to be handled” in order “to buy time.” That same evening, Mitchell’s chief assistant on the re-election committee, Frederick C. LaRue, arranged to have $75,000 delivered to Hunt’s lawyer.

Except for Nixon, everyone just named went to jail.

Meaning: To obstruct justice.

The softer language was important psychologically to the conspirators. As John Dean explained in a 1975 New York Times article: “If Bob Haldeman or John Ehrlichman or even Richard Nixon had said to me, ‘John, I want you to do a little crime for me. I want you to obstruct justice,’ I would have told him he was crazy. … No one thought about the Watergate cover-up in those terms—at first, anyway. Rather it was ‘containing’ Watergate.… No one was motivated to get involved in a criminal conspiracy to obstruct justice—but under the law that is what occurred.”

Meaning: The preferred pronunciation of CREP, acronym for Committee to Re-Elect the President.

The variant was popularized before the 1972 election—and well before the committee’s creepier activities were revealed to the world. Credit for it belongs not to a Democrat, as one might be forgiven for suspecting, but to Sen. Robert Dole, chairman of the Republican National Committee. He disliked the way the young know-it-alls on the re-election committee were ignoring the established party apparatus.

Meaning: To destroy evidence, specifically by tossing it into a body of water.

After E. Howard Hunt’s name was connected to the Watergate break-in, the safe in his office in the White House basement was drilled open and its contents turned over to John Dean. The safe contained, among other things, a revolver; bugging equipment; a psychological profile of Dr. Daniel J. Ellsberg, leaker of the Pentagon Papers ; a State Department cable that had been faked to make it appear that President John F. Kennedy had ordered the murder of President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam; and a dossier on Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. Dean asked the President’s chief domestic affairs adviser, John Ehrlichman, what he should do with these “sensitive materials.” Ehrlichman, according to Dean’s testimony to the Senate Watergate committee, suggested that he shred the documents and “deep-six” the attaché case containing the electronic gear.

Dean continued: “I asked him what he meant by ‘deep-six.’ He leaned back in his chair and said: ‘You drive across the [Potomac] river at night, don’t you? Well, when you cross over the river on your way home, just toss the briefcase into the river.’”

But Dean had qualms about destroying evidence. Instead he put the documents in a sealed envelope and gave it to Gray, acting director of the FBI. This way, if asked, he could say honestly that he had turned the evidence over to the FBI. At the same time, he counted on Gray to be a good soldier and not let the material become public. Gray did not disappoint. He took the files home and burned them at the end of 1972 with trash left over from Christmas.

Deep-six is old naval slang for a watery grave or for the act of jettisoning something from a ship.

Meaning: An anonymous source; specifically, the highly placed governmental individual who provided information that helped Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post unravel key strands of the Watergate scandal.

Deep Throat provided “deep background”—that is, he confirmed information that the reporters had obtained elsewhere and provided perspective on events—but he could never be quoted directly. According to All the President’s Men , the best-selling book that Woodward and Bernstein wrote about their exploits, Deep Throat was in the upper echelons of the Executive branch. He met Woodward periodically in an underground parking garage. Meetings were set by prearranged signals: When Woodward wanted a meeting, he moved a flower pot with a red flag to the rear of the balcony of his apartment; on the rare occasions when Throat wanted a meeting, the time would be indicated by a drawing of clock hands in the lower corner of page 20 of the copy of The New York Times that was delivered to Woodward early each morning. How Deep Throat got to his copy of the paper, the reporter said he did not know.

Woodward at first referred to his anonymous sources as “my friend.” It was the Post’s managing editor, Howard Simons, who dubbed him Deep Throat, a play on the title of the smash-hit pornographic movie starring Linda Lovelace that had opened earlier in 1972.

To this day the reporters have kept Deep Throat’s true identity secret. Some people suspect he may have been a composite. Whatever, the notoriety of the nickname has made the term generic for any highly placed anonymous informer.

Meaning: Prominent opponents of President Richard M. Nixon.

The existence of this list was disclosed by John W. Dean in testimony to the Senate Watergate committee on June 26, 1973. Responding to a question by Sen. Lowell Weicker, of Connecticut, Dean said, “There was also maintained what was called an enemies list, which was rather extensive and continually being updated.”

Nixon had personally requested the list, as indicated by remarks to Dean on September 15, 1972: “I want the most comprehensive notes taken on all those who tried to do us in. They didn’t have to do it. If we had had a very close election and they were playing the other side I would understand this. No—they were doing this quite deliberately, and they are asking for it and they are going to get it. We have not used the power in this first four years as you know. We have never used it. We haven’t used the Bureau [the FBI] and we haven’t used the Justice Department, but things are going to change now. And they’re going to get it right.”

By the time Dean testified to the Senate committee, the enemies list included the names of twenty-one organizations and some two hundred individuals, among them all twelve African-American House members, some fifty members of the media, and assorted business executives, celebrities, antiwar protesters, and so on.

In some circles, being on the list became a badge of honor.

Meaning: A constitutional doctrine that can be used to cloak criminal actions .

The Nixon administration expanded the doctrine most dramatically when John Mitchell’s successor as Attorney General, Richard G. Kleindienst, told a Senate panel on April 10, 1973, that executive privilege applied to all 2.5 million employees of the executive branch—and that if Congress didn’t like it, it could impeach the President. (This was well before the possibility of impeachment seemed serious to most people.)

Nixon, announcing his decision on April 29, 1974, to release the initial batch of White House transcripts—1,254 pages’ worth—justified executive privilege by saying: “Unless a President can protect the privacy of the advice he gets, he cannot get the advice he needs. This principle is recognized in the constitutional doctrine of executive privilege. … I consider it to be my constitutional duty to defend this principle.”

Behind closed doors Nixon and his aides discussed the concepts in less elevated terms. Thus Ehrlichman advised the President on March 22, 1973, that in some circumstances “you could even screw executive privilege.” Later in the same meeting Haldeman warned Nixon: “On legal grounds, precedence, tradition, constitutional grounds and all that stuff you are just fine, but to the guy who is sitting at home who watches John Chancellor. … he says, ‘what the hell’s he covering up, if he’s got no problem why doesn’t he let them go talk.’”

Such conversations led Leon Jaworski, the second special prosecutor on the case, to conclude, as he wrote in his memoir, The Right and the Power, that “the tapes showed that ‘national security’ and ‘executive privilege’ were not used in their true meaning at the White House but were cynical devices to hide the facts.” The United States Supreme Court agreed, deciding 8-0 on July 24, 1974, in United States v. Nixon that the President had to surrender the most damaging tapes (including those at variance with so many of his previous statements) because “the generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.”

Meaning: A vulgar or profane word or phrase.

The White House conversations were cleaned up in transcript form with many a parenthetical “expletive deleted.” Usually this was done simply for decency’s sake, as in, from an Oval Office meeting on September 15, 1972, Nixon’s “Yes [expletive deleted]. Goldwater put it in context when he said, ‘[Expletive deleted] everybody bugs everybody else.’“

Occasionally the parenthetical comment blurred the meaning of a statement to the President’s advantage. Thus, referring to E. Howard Hunt’s demand for some $120,000 in hush money, the transcript of Dean’s morning meeting with Nixon on March 21, 1973 (see cancer on the Presidency), has the President saying: “[Expletive deleted] get it. … In a way that—who’s going to talk to him?” The President’s defenders managed to interpret this passage as a hypothetical discussion. When the actual tape was played for the special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, however, what he heard the President say, was “Well, for Christ’s sake, get it.…”—a direct order to get the money to buy off Mr. Hunt. It was one of the items on the tapes, Jaworski said, that “particularly stuck in my craw.“

Expletive deleted has been adopted widely.

See also stonewall.

Meaning: An erasure.

Gap was the discreet term used by President Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, when testifying on November 26, 1973, before U.S. District Court Judge John J. Sirica, to describe an eighteen-and-a-half-minute erasure in a tape recording of a meeting on the morning of June 20, 1972, between Nixon and his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman.

This tape was one of a group of nine that Archibald Cox, the first Watergate special prosecutor, subpoenaed on July 23, 1973, just days after Alexander P. Butterfield, a former presidential aide, revealed to staffers of the Senate Watergate committee that the President had a voice-activated system for recording conversations and telephone calls. This news dramatically changed the course of the investigation by raising the possibility that John Dean’s Watergate testimony could be verified by the tapes.

The June 20, 1972, tape was high on Cox’s list because this was the first working day in the White House after the break-in at the DNC offices on June 17. Notes that Haldeman made at the time indicated that he had briefed the President about the break-in but gave no details of the discussion. Hence the prosecutor’s need for the tape.

After resisting the subpoena for three months, the White House was forced by court decisions and public pressure to agree to surrender the tapes. Embarrassing disclosures followed immediately. First, the White House announced on October 31, 1973, that two of the nine tapes did not exist. Then, three weeks later, the mysterious gap was discovered. This last was a real bombshell, especially because it came just after Nixon had assured a meeting of Republican governors that there would be no more Watergate “bombshells.”

Woods testified that while transcribing the tape, she had accidentally erased perhaps five minutes when interrupted by a phone call. She said she had pressed the “record” button instead of the “stop” button and then kept her foot on the machine’s control pedal while speaking into the phone. Not everyone accepted this explanation; the maneuver would have been difficult to perform because of the distance between the recording machine and the telephone in her office.

A panel of electronics experts convened by Judge Sirica concluded that the gap was not accidental but the result of anywhere from five to nine separate erasures. The identity of the responsible party was never determined; too many people, including the President, had had access to the tape. Haldeman’s successor as chief of staff, Gen. Alexander Haig, suggested that the gap was caused by a “sinister force.” The guilty party, whoever it was, probably bought Mr. Nixon an extra nine months in the White House, as noted in at variance with .

Meaning: A scandal or cover-up; a pejorative suffix, inspired by Watergate. Most -gate terms are ephemeral, fading from use as the events that inspired them recede in time. The suffix itself lives on .

Almost every administration since Mr. Nixon’s has had one or more - gates . A random sampling: the Ford administration’s Koreagate , Carter’s Billygate and Lancegate , Reagan and Bush’s Irangate (‘also called armsgate and contragate ). Bill Clinton has survived, so far, travelgate , White-watergate , and, most recently, Indogate (‘involving campaign contributions from Indonesia).

Meaning: False; perhaps the most famous single Watergate word.

Press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler was badgered into uttering this word on the afternoon of April 17, 1973, in what amounted to a blanket retraction of almost everything the White House had been saying about Watergate for the preceding ten months. This is how it happened:

Late on the afternoon of April 17, President Nixon came to the White House press room to announce that he had begun “intensive new inquiries” into the Watergate “matter” as a result of “serious charges which came to my attention” on March 21 (meaning John Dean’s cancer on the Presidency speech to him). Already, said the President, these charges had produced “major developments” and “real progress … in finding the truth” about the break-in.

Nixon’s statement implied falsely that everything Dean had said on March 21 was news to him, but reporters did not know this at the time. They did realize, though, that this announcement conflicted with one Nixon had made on August 29, 1972. Then, citing a nonexistent report by Dean, he had assured the nation, “I can say categorically that his investigation indicates that no one in the White House staff, no one in the Administration, presently employed, was involved in this very bizarre incident.”

Nixon declined to take questions regarding his new announcement. That job was left to Ziegler, who had consulted in advance with the President about how to reconcile the two statements. From the transcript of their meeting:

“NIXON: You could say that the August 29 statement—that … the facts will determine whether that statement is correct, and now it would be interfering with the judicial process to comment further.

“ZIEGLER: I will just say that this is the operative statement.”

When he met the press, Ziegler repeated perhaps half a dozen times the line “This is the operative statement.” Finally R. W. Apple, of The New York Times, asked if it would be fair to infer from this that the previous statement “is now inoperative.” Ziegler fell into the trap. “The others are inoperative,” he said in agreement. Thus he disavowed all his previous denials of White House involvement in Watergate. His credibility and, by extension, Mr. Nixon’s were left in tatters.

The cover-up was beginning to come apart. The President knew that John Dean had begun talking to federal prosecutors and that he had implicated H. R. Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman. Two weeks later Nixon would make a dramatic effort to wipe the slate clean, announcing on April 30 the resignations of Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Dean, and Richard Kleindienst.

After Ziegler, you’d think that no one in political life would ever use inoperative again. Yet, in April 1994, when records turned up showing that Hillary Rodham Clinton had traded in commodities for longer than previously stated, a “senior official” (perhaps a young one, with no firsthand memory of Watergate) described the earlier White House account as “inoperative.”

Meaning: To clean dirty money, removing any trace of its origin; an underworld term popularized by Watergate .

Reporting on the FBI’s investigation of the money found on the Watergate burglars, John Dean told H. R. Haldeman: “They traced one check to a contributor named Ken Dahlberg. And apparently the money was laundered out of a Mexican bank and the FBI has found the bank.”

The burglars had packs of hundred-dollar bills (see at variance with ) that had come from a special fund that Creep had created for financing political espionage. (When Carl Bernstein, of the Washington Post , asked John N. Mitchell for his comments on a story about the secret fund on September 29, 1972, the by then former director of Creep said of the newspaper’s publisher, “Katie Graham’s gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” The Post went ahead and published, deleting the anatomical reference. The next morning Mrs. Graham asked Bernstein if he had any more messages for her.)

The FBI learned within days of the break-in that the bills in the burglars’ possession came from contributions to the campaign committee by Kenneth H. Dahlberg, a Minnesota businessman, and Manuel Ogarrio, a Mexican lawyer (who were themselves actually funneling money from other contributors who wanted to keep their identities secret). The checks from Dahlberg and Ogarrio were passed by Creep to Bernard Barker, one of the five men later caught in the Watergate break-in. He deposited them in his account in a Florida bank, withdrew the whole $114,000 in hundred-dollar bills, and then gave the C notes to Creep’s counsel, G. Gordon Liddy, who in turn gave them to the campaign committee’s treasurer, Hugh Sloan. When the time came to pay for the break-in, some of the same bills were returned to Barker and his cohorts. And the FBI, as Dean told Haldeman, was hot on the trail.

As the Watergaters got deeper into the conspiracy and needed hush money for E. Howard Hunt (see cancer on the Presidency), they discovered that they had a lot to learn about laundering. Thus Dean and Haldeman briefed the President on March 21, 1973:

“ DEAN : You have to wash the money. You can get one hundred thousand dollars out of a bank and it all comes in serialized bills.

“ NIXON: I understand.

“ DEAN: And that means you have to go to Vegas with it or a bookmaker in New York City. I have learned all these things after the fact. I will be in great shape for the next time around.

“ HALDEMAN : [Expletive deleted.]

To allow someone to undergo a long, public ordeal.

A coiner of vivid phrases (like the big enchilada ), John Ehrlichman produced this one in the course of a telephone conversation with John Dean on March 6, 1973. The subject was L. Patrick Gray, the FBI’s acting director.

The Senate hearings on Gray’s nomination to become permanent director had begun on February 28. For Gray, it had been a rough week. This was the first chance anyone had had to grill a member of the administration under oath.

Questions by members of the Judiciary Committee soon elicited disturbing information. Gray had allowed John Dean and Creep lawyers to monitor the FBI investigation of the Watergate break-in. He had not objected when the Justice Department placed restraints on the FBI that limited its inquiries insofar as possible to the burglary itself.

The longer Gray testified, the worse became the chances for his nomination. By March 6 Dean suspected that the committee would not vote on the nomination until it had had a chance to question himself and other White House staffers whose names Gray had mentioned. Yet the President had decided to claim executive privilege to keep his aides from testifying. In that case, Dean told Ehrlichman, the nomination might be left hanging until the courts ruled on the President’s claim. Thereupon Ehrlichman produced his immortal reply, saying, in full, “Well, I think we ought to let him hang there. Let him twist slowly, slowly in the wind.”

And twist he did—for another month. The White House did not formally withdraw Gray’s nomination until April 5.

Meaning: Crimes.

Former President Richard M. Nixon made no admission of guilt when accepting the pardon that President Gerald R. Ford offered him on September 8, 1974, for any federal crimes he “committed or may have committed.” Instead Nixon spoke in this vein: “No words can described the depths of my regret and pain at the anguish my mistakes have caused the nation and the Presidency. … I know that many fair-minded people believe that my motivation and actions … were intentionally self-serving and illegal. I now understand how my own mistakes and misjudgments have contributed to that belief and seem to support it. …”

The admission of “mistakes” has since become a mantra for politicians seeking to distance themselves from unsavory and unethical, if not downright unlawful, activities. Thus, questioned at a news conference on January 29, 1997, about Democratic fund-raising practices, President Bill Clinton noted: “It costs so much money to pay for these campaigns that mistakes were made here by people who did it deliberately or inadvertently.”

Meaning: Nickname of the Special Investigations Unit that President Nixon created to plug leaks and, as he described it in a statement to the press on May 22, 1973, “investigate other sensitive security matters.”

Formation of the unit, in June 1971, was inspired by one of the greatest leaks of all time—the Pentagon Papers , a multivolume documentary study of how the United States became involved in the Vietnam War. The unit was supervised by John D. Ehrlichman, who named as its director his chief assistant, Egil Krogh, Jr. Members included David R. Young, Jr., an aide to National Security Adviser Henry A. Kissinger; G. Gordon Liddy; and E. Howard Hunt, Jr., a former CIA agent. Their most famous operation was a break-in at the offices of Dr. Lewis B. Fielding, a psychiatrist in Los Angeles, one of whose patients had been Daniel Ellsberg, the man who had leaked the Pentagon Papers. The motive for the break-in was to obtain personal information about Ellsberg that could be used to smear him publicly.

The Fielding break-in, carried out over the Labor Day weekend of 1971, foreshadowed the Watergate break-in of the following June. The operation was planned and supervised by Hunt and Liddy, who hired three Cuban-Americans to do the actual dirty work. The burglars ransacked Fielding’s desk and files, making quite a mess, but found nothing relating to Ellsberg.

The failed operation had large repercussions. After the Watergate burglars were brought to trial in January 1973, the Fielding break-in became one of the “seamy things” that Hunt threatened to expose if he was not paid off (see cancer on the Presidency ). Later, in mid-April of 1973, John Dean revealed some of the details to federal prosecutors, and information about the break-in became one of the grounds on which the government’s case against Ellsberg was dismissed.

Of the plumbers, only one, David Young, avoided engaging in criminal acts and thus stayed out of prison. He gave the unit its enduring name, however. Reportedly inspired by a relative, who told him that his grandfather, a plumber, would have been proud of him for combating leaks, he placed a sign, MR. YOUNG—PLUMBER, on the door of room 16 in the basement of the Executive Office Building, where the Special Investigations Unit was headquartered.

Meaning: The night of October 20, 1973, possibly the most tumultuous in American political history, when the special Watergate prosecutor and the nation’s two top law officers lost their jobs within the space of an hour and a half .

The cause of the bloodbath was a subpoena that the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, had issued on July 23 for tapes and other records relating to nine key White House meetings, including the one between Nixon and H. R. Haldeman that turned out to have the infamous gap . President Nixon resisted Cox’s demand on the ground of executive privilege . Turning over the tapes, White House lawyers asserted, would jeopardize “the independence of the three branches of government.” The subpoena was upheld, however, by the presiding judge at the Watergate trials, U.S. District Court Judge John J. Sirica, and then by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The White House offered a compromise. Transcripts would be supplied but not the tapes themselves, with the transcripts to be authenticated by John C. Stennis, a seventy-two-year-old Democratic senator from Mississippi. Cox rejected this. Nixon, who had been anxious for some time to rid himself of Cox, proceeded to harden his position. Not only would the special prosecutor have to accept the White House’s offer, like it or not, but he would have to “make no further attempts by judicial process to obtain tapes, notes, or memoranda of Presidential conversations.” The President knew that Cox could not accept this restriction.

Nixon issued his directive on Friday evening. Cox held a press conference early Saturday afternoon. Prevailing wisdom in the White House was that he would announce his resignation. He did not. Instead he said he would continue to press for the tapes, and if Nixon continued to refuse to turn them over, he might ask to have the President cited for contempt of court.

Almost immediately the White House chief of staff, Gen. Alexander Haig, telephoned Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson and ordered him to fire Cox. Richardson said he couldn’t do that. At his Senate confirmation hearings he had pledged to give the special prosecutor a free hand; only in the event of “extraordinary improprieties” would he dismiss him. Richardson also had made this promise to Cox himself when he hired his former Harvard Law professor as special prosecutor.

Richardson then asked Haig for a meeting with the President so that he could tender his resignation. When the two met, at 4:30 P.M., Nixon tried to dissuade Richardson, urging him to put the national interest above his personal pledge. His resignation, Nixon suggested, might interfere with his efforts to bring peace to the Middle East. Richardson was shaken but not swayed. He felt he had no choice but to resign.

General Haig called Richardson’s deputy at the Justice Department, William D. Ruckelshaus, and told him that the President was ordering him to fire the special prosecutor. Ruckelshaus also preferred to resign.

Working his way down the chain of command, General Haig called the number three man in the department, Robert H. Bork, the solicitor general. Bork found that his conscience and sense of duty allowed him to accept the order. At about 6:00 P.M. he signed a White House-drafted letter firing Cox.

Press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler informed the world of what had happened at about 8:25 P.M. Ziegler said that the office of special prosecutor had been abolished. Its functions would be transferred back to the previously discredited Justice Department. The same evening, Haig dispatched FBI agents to seal the offices of Cox, Richardson, and Ruckelshaus.

For a very short while it seemed to some that Nixon had pulled off a remarkable coup. However, a tremendous surge of popular outrage over the weekend followed by the introduction of more than twenty bills in Congress the next week calling for an impeachment investigation forced the President’s hand. He agreed to yield up the tapes, and on November 1 a new special prosecutor was named: Leon Jaworski, a Houston lawyer.

Meaning: Indisputable proof of guilt .

As Americans pored over the twelve-hundred-plus pages of White House transcripts publicly released on April 30, 1974, the proverbial smoking gun in the hand of a murderer became a metaphor for the elusive piece of evidence needed to prove that President Nixon himself had conspired to obstruct justice. The evidence in the transcripts was suggestive but not conclusive, partly because they had been cleaned up (see expletive deleted and stonewall ) and partly because of the ambiguous, meandering nature of many of the presidential conversations. Not until August 5, 1974, when the President was forced to turn over the tape of his meeting on June 23, 1972, was the smoking gun found (see at variance with ). After that Nixon was President for only four more days.

Smoking gun also outlived Watergate. For example, Thomas L. Friedman used the term in a New York Times column earlier this year: “Officials stress that while they have some circumstantial evidence that Iran may be linked to the Dhahran bombing, there is still no ’smoking gun.’”

Meaning: To impede an investigation by refusing to reveal information; to cover up.

President Nixon and his men talked a lot about stonewalling. Thus, discussing prospective testimony of H. R. Haldeman’s aide Gordon C. Strachan, who had known about Creep’s espionage plans, John Dean told Nixon on March 13, 1973: “Strachan is as tough as nails. He can go in and stonewall and say, ‘I don’t know anything about what you’re talking about.’”

Nixon himself told his chief aides on March 22, 1973, referring to forty coming hearings of the Senate Watergate committee: “I don”t give a shit what happens. I want you all to stonewall it, let them plead the Fifth Amendment, cover-up, or anything else, if it’ll save it—save the whole plan. That’s the whole point.”

Meaning: The Watergate break-in.

Very early on the morning of June 17, 1972, Frank Wills, a watchman at the Watergate hotel-office-apartment complex, noticed that doors connecting an underground parking garage to the main office building had been taped to prevent them from locking. He removed the tape. Returning to the area on his rounds a half-hour later, at about 1:50 A.M., he saw that the locks had been retaped. Wills telephoned the police. Three members of the tactical squad of the Washington metropolitan force responded. They proceeded to search the building from the top down. In the sixth-floor offices of the Democratic National Committee, they found Creep’s security coordinator, James W. McCord, Jr., and four men from Miami, who proved to have ties to the CIA and anti-Castro groups. The intruders were outfitted with cameras, telephone bugging equipment, and a walkie-talkie.

As news items go, this seemed at first to be an odd but distinctly minor incident. In New York the television announcer Jim Hartz could barely control his laughter as he read the bulletin. Two days later, on June 19, speaking to reporters in Key Biscayne, Florida, where the President was vacationing, Ron Ziegler fended off questions about the break-in, saying, “I am not going to comment from the White House on a third-rate burglary attempt.”

Actually this was the second “third-rate” burglary at the DNC offices. The first had taken place on Memorial Day weekend, when McCord and the Miamians had photographed documents and placed bugs on telephones used by the Democratic party chairman, Lawrence F. O’Brien, and another party official. Unfortunately the bug on O’Brien’s phone hadn’t worked well. It was mainly to replace this bug that the burglars returned to the scene two weeks later.

When Wills discovered the taped door and called the police, the dispatcher initially radioed a uniformed officer. But this policeman, low on gas and behind on paperwork, asked if someone else could respond, and the plainclothes tactical officers, driving an unmarked car, were nearest to the Watergate complex. From a room in the Howard Johnson Motor Inn across the street, another member of the Hunt-Liddy team, Alfred C. Baldwin III, was monitoring the break-in, walkie-talkie in hand. Baldwin, a former FBI agent, saw the three policemen arrive but was not alarmed because they were dressed casually. Not until lights began going on and off as the search progressed, and he saw men with flashlights and guns in their hands, did Baldwin figure out what was happening. The burglars had turned off their walkie-talkie, but Baldwin was able to warn Hunt, enabling him and Liddy to depart quickly and quietly from the hotel section of the complex. Had a uniformed officer in a marked car appeared and Hunt gotten the warning earlier, he probably would have been able to alert McCord and the Miamians in time for them to escape.

The Watergate scandal—and its subsequent enrichment of our language—would never have happened.