The wrecker’s ball swings in every city in the land, and memorable edifices of all kinds are coming down at a steady clip.

-

February 1970

Volume21Issue2

There are places on this earth, in Europe particularly, where conservation is taken to mean the preservation of the notable works of man as well as nature. Magnificent old railroad stations and churches, public buildings, historic houses, architectural landmarks of all kinds, are valued for their beauty or for the memories they evoke, for the sense of continuity they give a place, or, often, just because they have been around a long time and a great many people are fond of them. But here in America we don’t — most of us, anyway — seem to feel that way.

We have, apparently, a traditional, perhaps congenital, passion for forever destroying and building anew. A hundred years ago in Harper’s Weekly one observer described New York as “a series of experiments, and every thing which has lived its life and played its part is held to be dead, and is buried, and over it grows a new world.”

Now that spirit has been institutionalized officially: we call it urban renewal. There may come a time, of course, when a different view prevails. There are even hopeful signs. In Lexington, Kentucky, a number of people have placed themselves in front of bulldozers in order to stop the demolition of several blocks of fine old houses. In Baltimore, the old B&O station is functioning splendidly as an art school. In Washington, Congress has at long last decided to do something about preserving the Frederick Douglass mansion. In the meantime, however, the wrecker’s ball swings in every city in the land, and memorable edifices of all kinds are coming down at a steady clip.

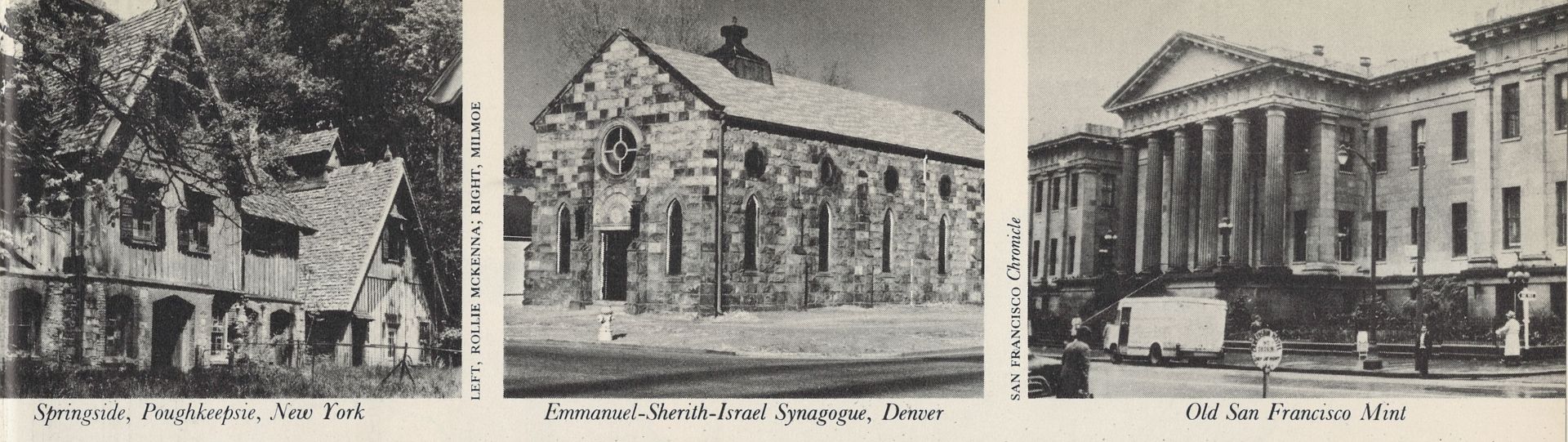

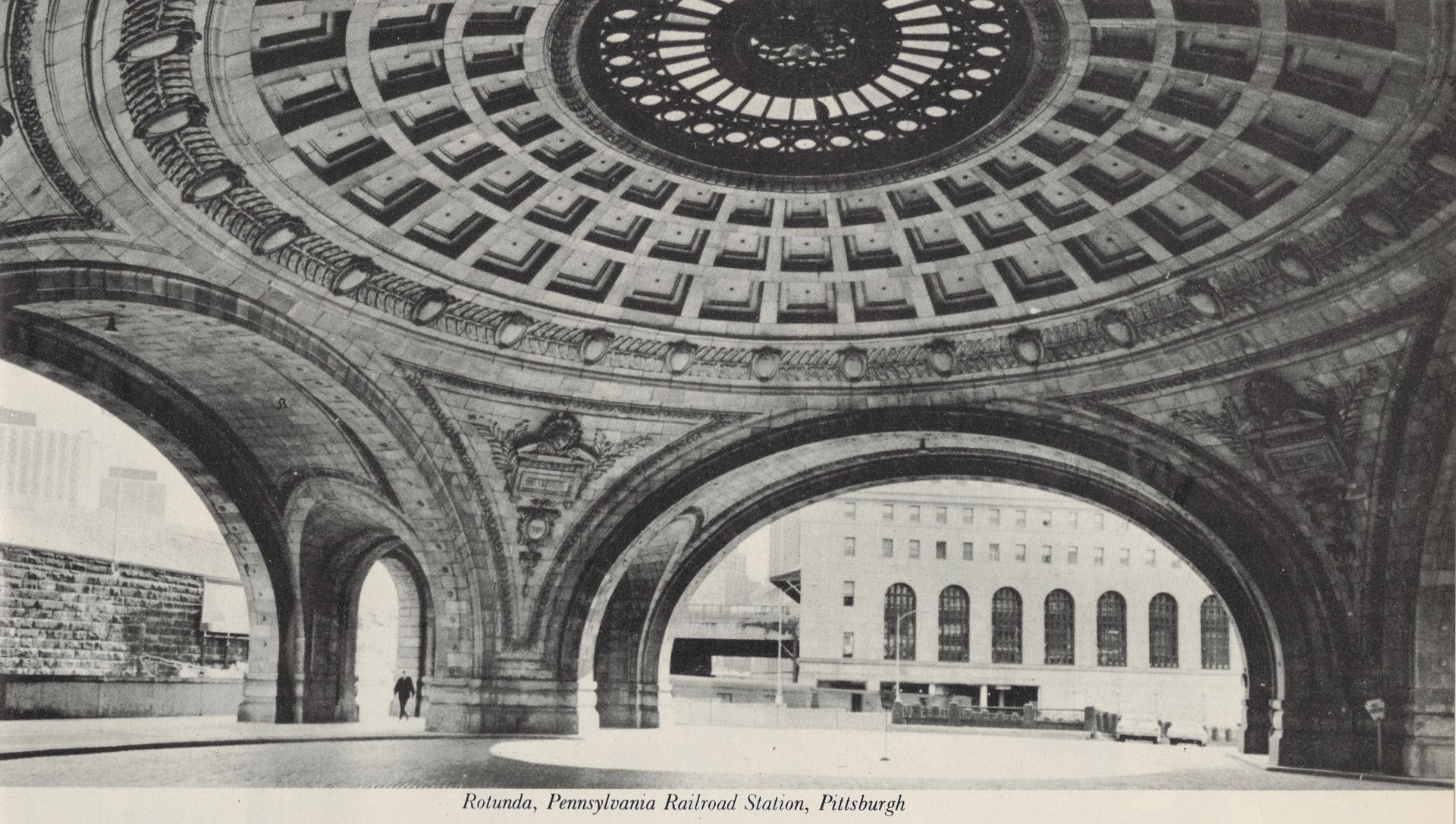

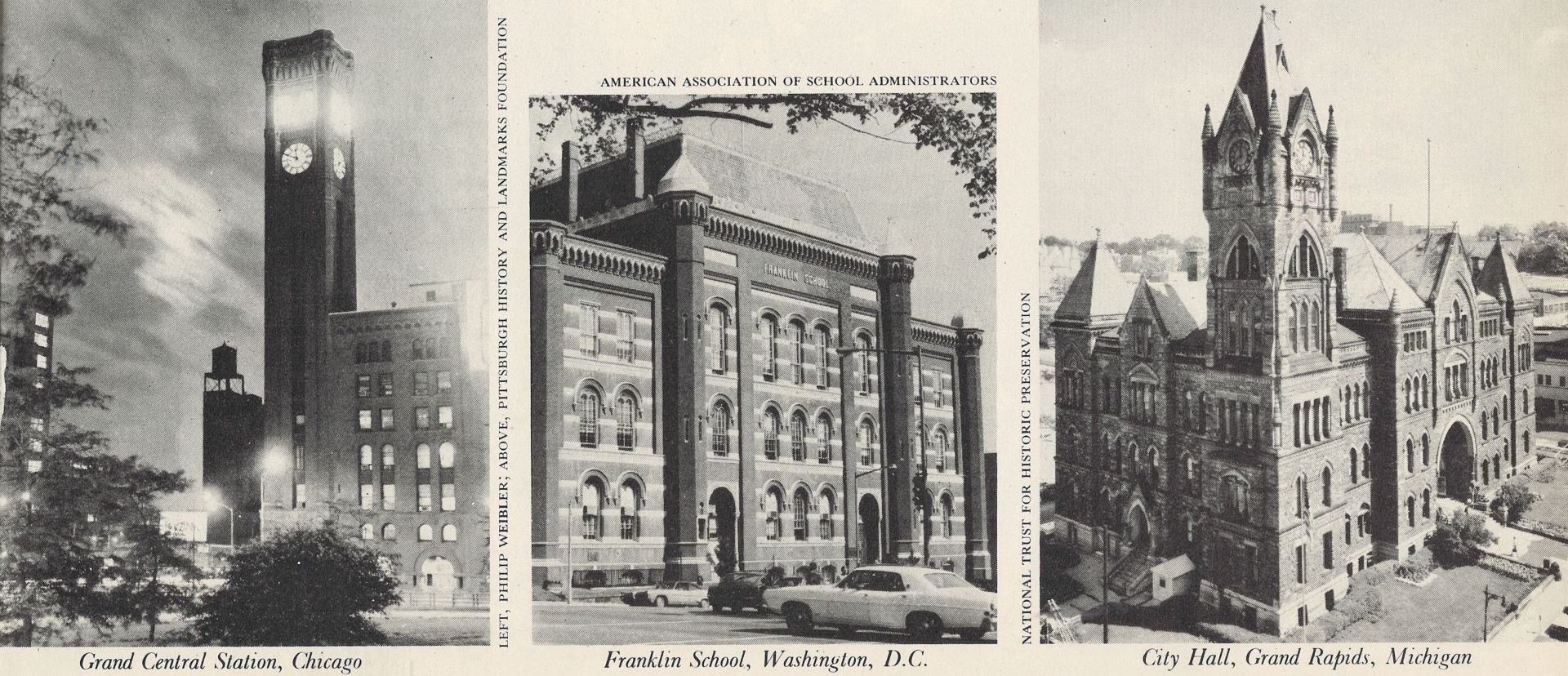

Listed here, for example, is a current wrecker’s dozen, thirteen doomed American landmarks. Seven of them are pictured here, and all of them at this writing are scheduled to be transformed into rubble.

Chicago: The old Grand Central Station and clock tower, completed in 1890 and long considered one of the finest buildings of its kind in the country.

Denver: The Emmanuel-Sherith-Israel Synagogue, built in 1876. It is one of the oldest synagogues in the West and one of several handsome structures to be torn down as part of a 169-acre urban renewal project.

Destrehan, Louisiana: The Destrehan Manor House, dating from the latter part of the eighteenth century and one of the oldest remaining plantation houses in Louisiana.

Grand Rapids, Michigan: City Hall, a superb example of stone Victorian Gothic and one of the few remaining Grand Rapids buildings with any character.

Hudson, New York: The General Worth Hotel, built in 1837 and a prime specimen of Greek Revival architecture in America.The Hill (also in Hudson), built in 1796 by Henry Livingston, Revolutionary soldier and Supreme Court justice. This historic mansion overlooking the Hudson River is modelled after a Palladian villa.

Los Angeles: The Walter Luther Dodge House, built in 1916 by Irving Gill, a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete. The building is a choice example of the early International style.

Pittsburgh: A huge domed entranceway into the Pennsylvania Railroad Station, completed in 1902. This great baroque rotunda is, in the view of some critics, the most majestic old structure in Pittsburgh.

Poughkeepsie, New York: Springside, the estate of Matthew Vassar, founder of Vassar College. It is the one remaining work of any consequence by the noted nineteenth-century architect Andrew Jackson Downing.

San Francisco: The Old Mint, designed by Alfred Bull Mullett in 1869. It began operating in 1874 and survived the earthquake of 1906. According to the National Trust, it is “the last great American building to be built in the Classic Revival Style and is the only monumental building of this type on the West Coast.”

Washington, D. C.: The West Front of the U. S. Capitol, the one remaining section of the original exterior and the only place where the designs of Latrobe and Bulfinch can still be seen. It has been decided by the official Capitol Architect, J. George Stewart—who is not an architect—that the old walls should be removed in order to provide space for a $45,000,000 extension.

The Franklin School, which opened in 1869 and had then, as now, what its architect aptly described as “an air of importance not commonly accorded to brick buildings.” From here Alexander Graham Bell sent the first wireless telephone message in 1880.

The Alva Belmont House, which may be the oldest building on Capitol Hill; the earliest section is thought to have been built by Lord Baltimore in 1632. It was the home of Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury from 1801 to 1814. Gallatin was a prime proponent of the doctrine that good roads “strengthen and perpetuate” political union and liberty; his house is to be demolished in order to build a new Senate driveway.