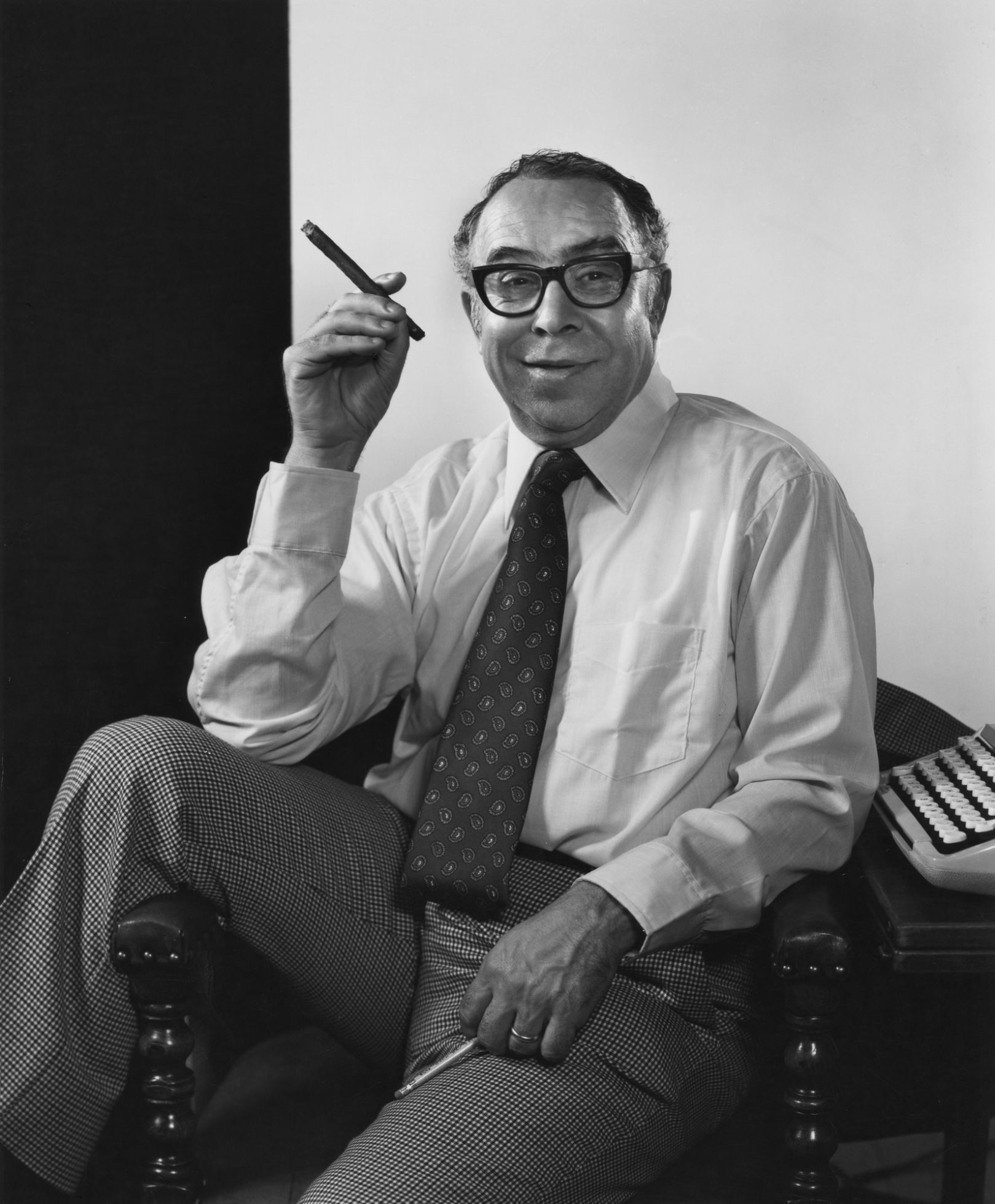

His political satire made Buchwald one of America’s most widely read columnists.

-

May 2023

Volume68Issue3

Editor’s Note: Michael Hill is a historical researcher and author who recently published his third book, Funny Business, a charming biography of Art Buchwald.

Before political comedians such as Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, and Trevor Noah, there was Art Buchwald. For more than fifty years, his Pulitzer Prize-winning column of political satire and biting wit made him one of the most widely read American humorists of his day. In fact, many observers singled him out as the Mark Twain of his time.

The power of Art Buchwald’s wit was legendary, with some describing him as “Will Rogers with chutzpah.” Dean Acheson, the venerable Washington “Wise Man” and former Secretary of State, called Buchwald the “greatest satirist in the English language since Pope and Swift.” New York Times columnist Arthur Krock once compared him to Anthony Trollope, and the novelist James Michener said that Buchwald had “one of the sharpest wits” he had ever known.

During his long career, Buchwald kept the Washington political establishment on its toes by poking fun at the powerful and the pompous, misguided bureaucrats, self-involved celebrities, and, as he was fond of saying, by “worshipping the quicksand” that ten different presidents of the United States walked on, starting with Dwight Eisenhower and continuing through George W. Bush.

At the height of his popularity, Buchwald’s three-times-a-week column was syndicated in 550 newspapers in one hundred countries. For over half a century, he was in the funny business, the political funny business, and, as you can well imagine, he found it everywhere. “The world is a satire,” he once said. “All I’m doing is recording it.”

In his day, his satirical jabs were called “Buchwald’s Buchshots” and, for over half a century, those shots seemed to be flying everywhere.

During the 1968 election, which pitted Richard Nixon against Hubert Humphrey and third-party candidate George Wallace, Buchwald described the choice the American people were faced with that fall like this: “Nixon looks like someone you wouldn’t buy a used car from, and Hubert Humphrey like a guy who bought one, and George Wallace like a guy who stole one.” When Ronald Reagan was elected president, Art wrote that Reagan had gotten the original idea for “trickle-down” economics after he saw Tip O’Neill “eat a bowl of soup.”

And, during the 1992 presidential campaign, when asked about Bill Clinton’s ability to supply him with satirical material if elected, Buchwald quipped, “As soon as Clinton said he smoked marijuana but didn’t inhale – I knew my humor column was safe.”

During his long career as a satirist, Art was fortunate to have one or two political scandals come his way, but it was the Watergate affair that really put a smile on his face and revved up his typewriter. “I consider myself the cruise director on the Titanic,” he told one crowd. His greatest concern about Nixon, he playfully told an audience at the height of the scandal, was that the president might eventually be driven from office. “Let me make this perfectly clear,” he repeated time and time again. “I’m neither for impeachment nor resignation. As a humor columnist, I need Nixon. He’s been great for me. I’m going to run him for a third term.”

Like many Americans of my generation and older, I loved reading Buchwald’s column when I was in high school and college. I once had the pleasure of meeting Art while I was a press assistant for Vice President Walter F. Mondale. He was kind, gentle, and, of course, funny.

One of the joys of Art’s offbeat humor, for me and millions of other readers, was that he always provided a welcome tonic against the grim front-page headlines about Vietnam, Watergate, and the dangers of nuclear war. By using his gift to make people laugh – and at themselves – he was, in his own way, doing something good for the spirit of America. Once, in the late 1960’s, at the end of that tragic, turbulent, and divisive decade, Buchwald told an interviewer: “My function – if I have one – is sort of taking the steam out of everything. This is a very uptight country right now, and if you can take some of the pressure off, maybe you are doing a bigger service than changing things.”

So, when the Art Buchwald archive was opened at the Library of Congress in 2017, I leapt at the chance to do a book about his life, using the vast treasure trove of material in the collection to paint a portrait of his career through his private letters, speeches, toasts, and some of his best columns. The result was a book called Funny Business: The Legendary Life and Political Satire of Art Buchwald.

In my research, I learned that the great British humorist P.G. Wodehouse read Buchwald each morning, then clipped his column. Even one of America's most celebrated caped crusaders, “Batman” (actually, actor Adam West), began each day with a touch of Buchwald in the morning. Fellow columnist Ann Landers once told Buchwald that, on a flight from Paris to London, a man sitting next to her “almost fell out of his seat laughing” while reading one of his columns. “In fact,” she told him, “the stewardess came by and suggested that he strap himself in – at least until he finished your column.”

His barbs could get a chuckle out of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, as easily as they could out of President Dwight Eisenhower and William F. Buckley, Jr. And Barry Goldwater once told Art, “You are one of those people who have the ability to make us think, make us laugh, make us cry, and love our fellow man. For that, I thank you.”

But there were hazards in Art’s line of work, and sometimes, his satire landed him in hot water. After writing a column in December 1964, claiming that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, one of the most feared men in America, was nothing more than a “mythical person first thought up by the Reader’s Digest” magazine, Hoover ordered that a confidential FBI file be kept on Buchwald and his column.

Then, a year later, after Art wrote a biting column about Lyndon Johnson’s handling of the Vietnam War, some humorless White House official activated a secret surveillance of Buchwald by the National Security Agency.

At times, editors or political friends tried to muzzle him, but Buchwald would have none of it. He was a fierce defender of freedom of speech and freedom of satire. In the 1950s, at the height of Senator Joe McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade, Buchwald wrote a wickedly funny column mocking McCarthy. When he submitted the article to his editors, who were “deathly afraid” of McCarthy, they killed it. Undeterred, Art looked elsewhere and sold it to The New Republic.

Art’s life and career are truly a great American story. Although his humor looked easy – he said he could bang out his column in less than an hour and that his typewriter automatically stopped at 600 words – the truth is that nothing ever came easy to him.

From an early age, he was educated in the school of hard knocks, living in a series of foster homes in and around New York City.

“He was essentially an orphan, living in orphan asylums and foster homes,” his daughter, Tamara Buchwald recalls. “He had to hire a wino to play the role of his father so he could enlist in the Marines when he 16 years old and too young to join up.”

Read Art Buchwald's memories of boot camp and

serving in World War II in “I Was a Marine” in American Heritage.

But, early on, he learned that laughter and a smile could help overcome just about anything life could throw his way. In fact, it was early in his childhood, when he saw the bleakness of life all around him, that he said to himself: “This stinks. I’m going to become a humorist.” And his dream came true.

In 1948, three years after serving in World War II, Art made his way to Paris and, astoundingly, and with typical Buchwald chutzpah, talked his way into a job at the Paris Bureau of the New York Herald Tribune, one of the greatest newspapers in the world at the time.

Soon, his writings were so popular on both sides of the Atlantic that Art became the “man to read” and “the man to see.” And, during their fourteen years in Paris together, Art and his wife Ann lived a colorful and charmed life, hanging out with Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, Irwin Shaw, Ingrid Bergman, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

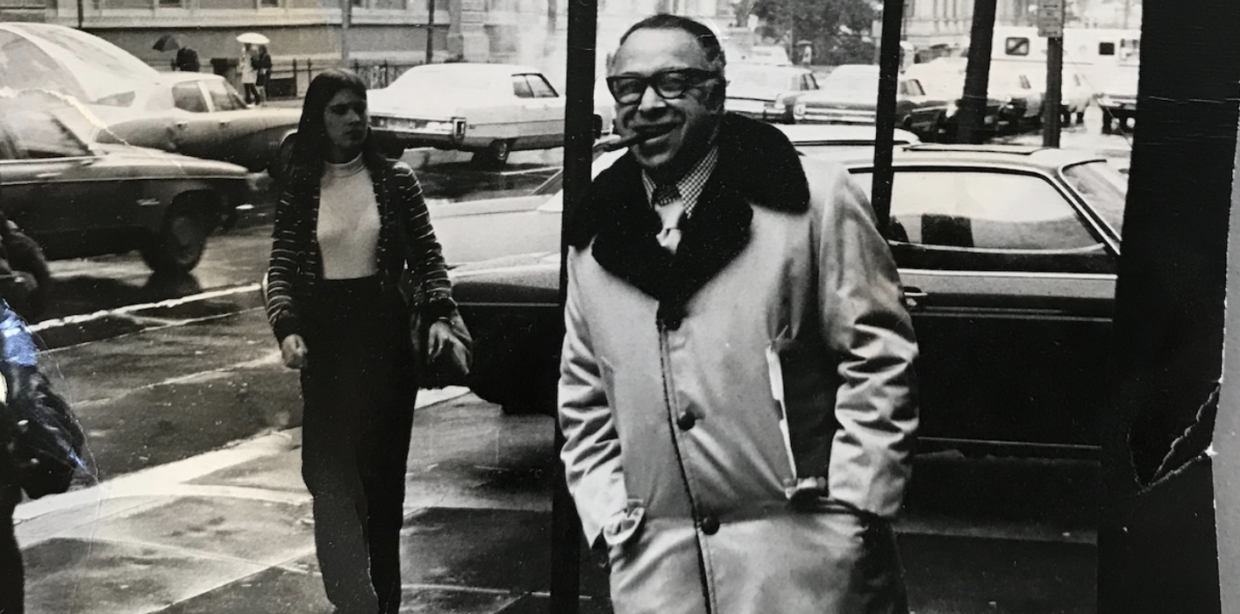

In 1960, after John F. Kennedy was elected, Buchwald saw the New Frontier as an exciting challenge and a source of fresh satirical material. So, he made the move to Washington, D.C. where, within a few years, his brand of humor and easygoing manner made him a national journalistic celebrity.

At the height of his career, he seemed to be everywhere. He had his own radio show; he had a segment on 60 Minutes; he did commentary at the national political conventions; he wrote a hit Broadway play, Sheep on the Runway; and nearly every year, he published a bestselling collection of his columns, selling up to 35,000 hardcover and 150,000 paperback editions.

Art loved being a journalistic celebrity. “I love it. I love what I’m doin’,” he told anyone who would listen. “I’m doing exactly what I want to do in life.” And, over the years, he was fortunate that the political zaniness of life in Washington, D.C. always gave him plenty of material to work with.

“The world is getting crazier. It’s gone absolutely mad,” he told a reporter back in 1977. “Sometimes, I really believe that this entire government’s only purpose is to provide me with material for my columns.”

One great advantage of the nearly ubiquitous Buchwald “brand name” was that he could use his influence and celebrity to give so much of his time to charitable causes. He took great delight each year in presiding over the famed Kennedy-family pet show as “ringmaster,” fully attired in a red hunting jacket, high leather boots, and a black top hat. (One year, Art was joined by another ringmaster, heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali, who served as a co-judge with him).

Each summer, he hosted the celebrated “Possible Dreams” auction on Martha’s Vineyard, which raised funds for local community programs such as affordable child care and mental health.

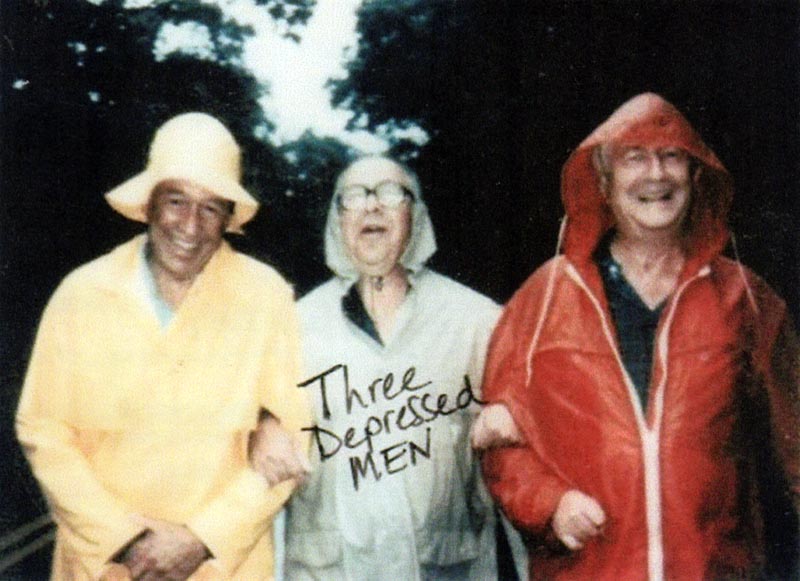

During my research on Art’s life, I discovered that, despite his public image as a funny man, there was a darker, more melancholy side to Art Buchwald. For more than forty years, he fought bravely against episodes of crippling depression, stemming from the “scars” he suffered as a foster child in New York City. It was a deep “dark secret” he kept hidden until the 1990s, when he went public about his lifelong struggle with depression.

To help others who suffered as he did, Art even went on the road with novelist William Styron and journalist Mike Wallace, two of his closest friends, who also battled depression, the trio dubbing themselves the “Blue Brothers” in appearances across the country.

And then, in the final years of his life, there was the way he bravely faced his own mortality – with typical grace, with typical chutzpah, and with typical good humor.

“If laughter is such good medicine,” he once joked. “then why won’t Medicaid and Medicare pay for it?” Once, when a friend visited him at his hospice in Washington, D.C., Art asked, “Did you have any trouble parking?” When, the friend replied, “Well, yes, in fact, I did.” Buchwald quipped, “Dying is easy. Parking is impossible.”

In January 2007, Art Buchwald finally passed from the scene, joining the great pantheon of American humorists, including James Thurber, Will Rogers, Dorothy Parker, and Robert Benchley.

He was mourned by friends, readers, and admirers everywhere. Humorist Dave Barry, a great friend, praised his singular sense of humor and view of life. Art was “funny without being mean-spirited, without being vicious, without being hateful ... He was just funny. He talked funny, he wrote funny, he lived funny and, damned, if he didn’t find a way to die funny.”

When former senator Gary Hart was asked about Buchwald’s legacy, he responded, “My dear friend Artie Buchwald, who, alas, is not here when we need him most. He was a dear man in a more decent and humane time. His like may or may not ever be seen again.”

But the most fitting words about Buchwald’s legacy were spoken by the master himself. Near the end of his life, as his kidneys were failing and time was running out, Mike Wallace asked him: “What are you going to leave behind?”

“Joy!” – Art bellowed – with a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye.