For a decade, the West has sleep-walked through a new kind of warfare being waged from Moscow. It took Putin's ground war against Ukraine to wake people up.

-

Spring 2022

Volume67Issue2

February 24, 2022 is a day that will live in infamy. Russian troops and tanks rolled into neighboring Ukraine, and Russian missiles rained down on civilian targets in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Mariupol. It will long be remembered, one hopes even more so, for the images of courageous Ukrainians taking up arms in defiance of the country’s invaders or finding refuge in the arms of welcoming neighbors.

But will it also be notable as the date when another war waged by Russia’s Vladimir Putin finally came up against determined opposition after a decade during which it encountered little resistance and in some cases cheerful acquiescence from those it targeted? Because make no mistake, Europe and the US have been on the receiving end of their own barrage—an onslaught of disinformation that has come close to destroying the values we once thought united us.

Just as it is by no means certain that tiny Ukraine can stand up to the bully next door indefinitely, nor is it clear that Russian influence—and those who came to power as a result of it—will vanish completely from our politics. But the events of the last few weeks, and in particular the last few days, give reason for optimism that we have reached a turning point.

Dezinformatsiya

The story of modern disinformation as a weapon of war is inextricably entangled with the story of Russia and Ukraine.

There is, of course, nothing new about governments in conflict (or even competition) using propaganda to further their aims. This is not the place for an exhaustive history of how disinformation has evolved over the past century (a history that includes Hitler and Goebbels and the Big Lie as well as the tactics developed by the corporate world to manufacture doubt over first tobacco and then climate change—a story for another time).

But it is interesting to note that almost exactly 100 years ago, in 1923, the Bolshevik Party Politburo approved the establishment of the "Disinformation Bureau" as a part of the Soviet security services. The Dezinformburo was intended to manufacture and disseminate forged documents that would lead Western governments to believe that both the Red Army and the Soviet economy were stronger than they really were.

A lot has happened since then, but there is widespread agreement among academics that Russia’s use of "dezinformatsiya" as a weapon against the West reached new levels of activity and success since 2014, when Putin’s anger at the removal of Russian puppet Viktor Yanukovych as president of Ukraine, swiftly followed by democratic elections, led him to embrace the Gerasimov Doctrine, based on the thinking of General Valery Gerasimov, Russia’s chief of the General Staff.

According to Gerasimov: "The very ‘rules of war’ have changed. The role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness…. The information space opens wide asymmetrical possibilities for reducing the fighting potential of the enemy," and he recommends that Russia should use "internal opposition to create a permanently operating front through the entire territory of the enemy state."

To the Kremlin, and Putin in particular, that meant using various tools of influence—hackers, bots, state-owned media, as well as so-called "useful idiots" on the ground—to shift public opinion in their favor or, in some cases, to create chaos as an end in itself.

After Yanukovych was deposed, the Kremlin fed extremists on both sides of the ensuing struggle—pro-Russian forces in eastern Ukraine and Ukrainian ultra-nationalists—a steady diet of disinformation in an attempt to heighten the conflict and ultimately provide Putin with the excuse he needed to invade and annex Crimea and support rebel factions in Donbas and Luhansk.

Putin went on to employ similar tactics in Estonia, Georgia and Lithuania, where complaints of Russian interference were followed by the success—to one extent or another—of political parties with financial ties to the Kremlin or to Russian oligarchs, all of which adopted a softer, more accommodating line on Russia.

As for Ukraine, the Institute for the Study of War published a study clearly delineating how "Russia has been using an advanced form of hybrid warfare in Ukraine since early 2014," deploying a type of information warfare the Russians call "reflexive control," which "causes a stronger adversary voluntarily to choose the actions most advantageous to Russian objectives by shaping the adversary’s perceptions of the situation decisively."

"It relies, above all, on Russia’s ability to take advantage of pre-existing dispositions among its enemies to choose its preferred courses of action."

The "stronger adversary" in this case was not, of course, Ukraine; rather it was the West, and the UK and US in particular, as Russia sought to destabilize the institutions—NATO and the European Union—that might stand in the way of its aggression.

The war in the shadows

In 2017, Molly McKew, a former aide to the president of Georgia and an expert in information warfare, explained the strategic reasons for Russia’s disinformation war in Politico: "The Russians know they can’t compete head-to-head with us—economically, militarily, technologically—so they create new battlefields. They are not aiming to become stronger than us, but to weaken us until we are equivalent."

A year earlier, two seismic events had shaken the Western world, and the Anglosphere in particular: first, in June, the UK voted to leave the European Union. Less than six months later, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. These were the two greatest triumphs of Russia’s "shadow war" on Western institutions.

Says McKew: "By selectively amplifying targeted disinformation and misinformation on social media—sometimes using materials acquired by hacking—and forging de facto information alliances with certain groups in the United States, [Russia] arguably won a significant battle without most Americans realizing it ever took place.

"Herein lies the real power of the Gerasimov-style shadow war: It’s hard to muster resistance to an enemy you can’t see, or aren’t even sure is there."

But, she adds, disinformation tactics "begin to fail when light is thrown onto how they work and what they aim to achieve." All of which helps explain why the powerful forces in the US and the UK that benefited from the shadow war were so determined to ensure that the necessary lights were never turned on.

In the UK in particular, a massive effort was undertaken to ensure that the influence of Kremlin disinformation and Russian money remained in the shadows.

There was circumstantial evidence, for sure, much of it in the public domain: the 2012 decision by Putin to have the Russian Embassy in London set up "Conservative Friends of Russia," building critical relationships with the governing party; the launch party for the group in the Russian embassy attended by Carrie Symonds (now Carrie Johnson); the fact that Mathew Elliott, another founding member of Friends of Russia, went on to become head of the Vote Leave campaign; the preferential deal offered by a Kremlin-supported bank to businessman Arron Banks, who donated £9m to Leave.EU, becoming the campaign’s biggest backer.

Reporter and disinformation specialist Carole Cadwalladr reported in The Guardian in 2018 that her own investigation into the connections between the Russian Embassy, Russian banks, London-based "think tanks", Brexit’s financial supporters and the Leave.eu campaign had resulted in a campaign of harassment and abuse targeting her personally.

"And it wasn't just Russia," Cadwalladr wrote in an excellent Twitter thread. "Companies such as Cambridge Analytica… Amoral opportunists such as [Brexit advisor Dominic] Cummings. They learned how to exploit a platform that was totally open—anyone could do so. And totally closed—no-one could see how. In 2016, we knew none of this. Russia and other bad actors acted with impunity… But now, through the sheer bloody hard work of academics, journalists and the FBI, we do know."

The unexpected victory for the Leave campaign, as well as the extraordinarily narrow margin, led to calls for an investigation into Russian involvement. But when the so-called Russia Report finally appeared in 2020, the only thing it proved conclusively was that the British government had failed to launch any serious investigation. The implications of this failure were obvious but not sufficient to prove that the Kremlin had manufactured Brexit.

The government "had not seen or sought evidence of successful interference in UK democratic processes" at the time, said the report. Stewart Hosie, a Scottish National Party MP who served on a committee attempting to understand what happened, explained: "The report reveals that no one in government knew if Russia interfered in or sought to influence the referendum because they did not want to know. The UK Government have actively avoided looking for evidence that Russia interfered."

Elsewhere, independent research from the City University of London, authored by Dr. Marco Bastos and Dr. Dan Mercea found that a legion of almost 13,500 fake Twitter accounts posted almost 65,000 messages during a four-week period before the Brexit referendum, with their content showing a "clear slant towards the leave campaign"—the bots were eight times more likely to tweet leave slogans than regular users. And the accounts disappeared shortly after the vote was complete.

According to Bastos, "We believe these accounts formed a network of zombie agents, given their orchestrated behavior and known bot characteristics…. They were invested in feeding and echoing user-curated, hyperpartisan and polarizing information."

Still, there was no smoking gun.

That was not the case in the US, where much of Russia’s interference in the 2016 campaign and its support for the Republican candidate occurred in plain sight. Russian hacking of Hillary Clinton’s email, Trump’s public call for them to release more details—were front-page news during the campaign, although other elements—particularly the social media misinformation campaign—remained in the shadows.

There were charges of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin, as well as suggestions that Putin had blackmail material that he was holding over the real estate magnate.

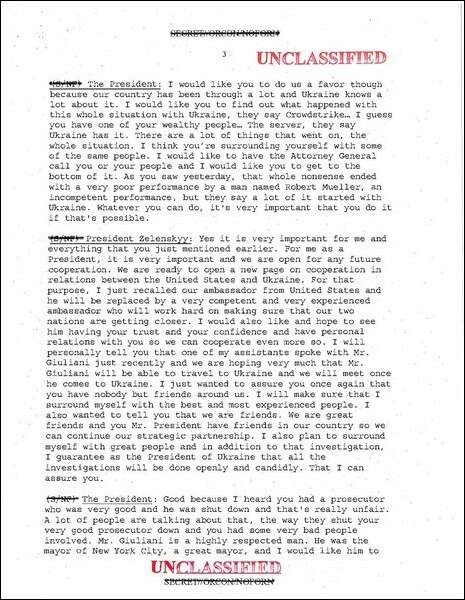

It matters not whether Putin expected Trump to win. The chaos was the point; the installation of the ultimate "useful idiot" was a bonus. It paid off in some specific ways—Trump refusing to sell stinger missiles to Ukraine unless Volodymyr Zelensky promised to manufacture evidence of corruption against Joe Biden (something he refused to do, an early indication of his strength of character); firing the troublesome US ambassador to Ukraine; the president’s attempts to sow disunity among NATO allies and weaken the alliance—all of which was the icing on top of a cake that consisted of the president’s eagerness to exploit divisions in American society, to pit Americans against each other.

In the end, the Democrats' focus on the (admittedly juicy) "kompromat" element of the Trump-Russia story and the possibility of collusion was, it is now apparent, irrelevant. But that focus meant that when the 448-page Mueller Report was published in April of 2019 most of the headlines, even in so-called liberal media, focused on the failure to prove "collusion" between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin, while ignoring the overwhelming evidence that Russia had interfered in US elections.

Mueller found that the disinformation campaign began in mid-2014, when employees of Russia’s Internet Research Agency visited the US to gather material that they would later use in their social media campaign. By 2016, Russia had set up fake social media accounts that reached millions of Americans directly—and of course millions more when those followers (including Donald Trump Jr. and Kellyanne Conway) re-posted disinformation that favored their candidate.

Mueller also found that the Russians created fake hashtags, like #kidsfortrump, organized key rallies (whether he knew it was an IRA event or not, candidate Trump posted his gratitude to the organizers of at least one Russian-sponsored event in Miami on Facebook), and—especially troubling—found clear evidence that Russia engaged in cyberattacks against private technology firms that make election software, as well as officials in several states and county governments.

And of course the report found that Russia’s intelligence service, the GRU, had hacked the Clinton campaign and released stolen data using fake personas such as DCLeaks and Guccifer 2.0.

Before the publication of the Mueller Report, the American media did not even know that they were in a war. After the report, they knew but did not care. Perhaps they assumed American people were so tired of the Mueller investigation that they were not interested in looking beyond the simple "no collusion" narrative. Perhaps social media companies were determined not to encourage any additional scrutiny of their shameful role in foreign interference. Perhaps mainstream journalists were too lazy to read 448 pages before moving on to the next "scandal du jour" (which the president seemed anxious to manufacture on a daily basis).

Whatever the causes, America’s response to the "shadow war" on its democratic institutions was little more than a collective shrug.

Biden turns the tide

In the spring of 2021, Russia began massing troops near Ukraine's borders in what it said were "training exercises." By November, however, satellite images were clearly showing an ongoing buildup of Russian forces near Ukraine with more than 100,000 troops deployed. On December 17, 2021, Putin presented a list of "security demands," asking NATO to pull back troops and weapons from eastern Europe and to make it clear that Ukraine could never be a member.

As the evidence mounted that Putin was planning an invasion, the Russian disinformation machinery was ramping up too.

To be fair, some of the voices raised against Biden and NATO were probably sincere. Others were merely 'useful idiots,' parroting the Russian line because it was in their interests—as political foes of the administration—to do so. But most of the arguments being made were suspiciously aligned with the propaganda coming out of the Kremlin.

There were attempts to portray Ukraine—which had stood up forcefully to corruption during the Trump administration—as corrupt. There were claims that many in eastern Ukraine—which has a substantial Russian population—would prefer to be part of Russia. There were attacks on NATO—which repeatedly said it would not accept Ukraine as a member—for its supposedly aggressive expansion. And there were, of course, charges that Biden—suffering from high inflation at home—was manufacturing a crisis to distract from his domestic problems.

Throughout this period, the Biden administration provided unprecedented transparency regarding what its intelligence sources were seeing: detailing movements of Russian special forces; refuting Russian claims of Ukrainian shelling or incursions along the border; exposing a Russian plan to create a video of a fake atrocity that might serve as a pretext for an invasion; informing reporters that the United States was seeing signs of Russian escalation and that there was a "credible prospect" of immediate military action.

It was a masterful use of public diplomacy and perhaps the first time in a decade that Putin’s "asymmetric" information war encountered forceful and savvy opposition.

As New York Times Pentagon correspondent Helene Cooper explained: "All told, the extraordinary series of disclosures has amounted to one of the most aggressive releases of intelligence by the United States since the Cuban missile crisis… In effect, the administration was warning the world of an urgent threat—not to make the case for a war, but to try to prevent one.

"The hope is that disclosing Putin’s plans will disrupt them, perhaps delaying an invasion and buying more time for diplomacy or even giving Putin a chance to reconsider the political, economic and human costs of an invasion." Ultimately, that was a forlorn hope, but at the same the Biden strategy succeeded, making it "more difficult for Putin to justify an invasion with lies, undercutting his standing on the global stage and building support for a tougher response."

And so it was that a frustrated Putin took to state-owned television in Russia and unleashed upon the world—and his own people—an unhinged rant that had many observers questioning his sanity, and which provided little doubt that he had no pretext for the invasion beyond wild accusations about a "genocide" in the Donbas region and plans for Ukraine to re-start its nuclear program (Ukraine had voluntarily given up its nuclear weapons in the 1990s in return for security guarantees from the US, the UK—and Russia).

Claiming to address Ukrainian soldiers, he said: "Do not allow neo-Nazis and Banderites to use your children, your wives and the elderly as a human shield. Take power into your own hands. It seems that it will be easier for us to come to an agreement than with this gang of drug addicts and neo-Nazis." (It seems worth noting at this point that Zelensky is Jewish.)

Max Boot, writing in the Washington Post, summed up Putin’s information war failings: "Thanks in part to the Biden administration’s strategic release of US intelligence, Putin was never able to concoct a ‘false flag’ incident to justify his offensive. He tried to but failed in goading the Ukrainian military into attacking Russian-speaking civilians in the east. When that didn’t happen, he unleashed his army anyway on the unbelievable pretext that he was combating ‘drug addicts and neo-Nazis’—words that make him appear delusional.

"The whole world could see what was actually happening: naked aggression reminiscent of the German and Soviet invasions of Poland in 1939."

In the end, the episode merely demonstrated the pitfalls of uninformed commentary. These people—many of whom had spent the past two years pretending they knew more about epidemiology than Anthony Fauci—clearly lacked the intelligence resources that were driving Biden’s response to the crisis, (perhaps failing to appreciate how much American intelligence has improved over the past 20 years) and so were left projecting their own biases onto a situation about which they knew nothing.

Beyond useful

The invasion itself did little to stem the flow of pro-Russian propaganda—initially at least. In the days immediately before the invasion and even beyond, the Fifth Column in America’s Fourth Estate was still promoting the Kremlin’s narrative. (I have provided no hyperlinks to any of these comments. I have no wish to drive traffic to any of these people. They are not hard to find, if you are so inclined.)

Tucker Carlson, the most popular host on the Fox News network, dismissed the idea that Putin was his enemy. "Why do I hate Putin so much? Has Putin ever called me a racist? Has he threatened to get me fired for disagreeing with him? Did he manufacture a worldwide pandemic that wrecked my business and kept me indoors for two years? Is he teaching my children to embrace racial discrimination? Is he making fentanyl? Is he trying to snuff out Christianity?"

A few weeks earlier, he made his allegiance even more clear: "I should say for the record, I’m totally opposed to these sanctions and I don’t think that we should be at war with Russia and I think we should probably take the side of Russia if we have to choose between Russia and Ukraine, and that is my view."

(Later, as the war rolled into its sixth day and Americans—even Republicans—showed increasing sympathy for the Ukrainians, Carlson responded to allegations that he was pro-Russia: "Why are they saying that? It doesn’t make sense." It should go without saying, but that kind of gaslighting is an integral element of the whole dezinformatsiya game.)

In a similar vein, former Trump aide Steve Bannon held a conversation with Eric Prince, founder of the "private security" firm Blackwater, that focused on "wokeness," which was presented as an evil far worse than invading a neighboring country and murdering civilians. "Putin ain’t woke," said Bannon, praising the authoritarian leader. "He’s anti-woke."

"The Russian people still know which bathroom to use," added Prince. Bannon asked how many genders there were in Russia. "Two," said Prince.

(Using those same criteria, it seems worth asking Carlson, Bannon and Prince whether they also regard the 9/11 terrorists as allies—after all, there are few people less "woke" than religious extremists.)

Another Fox News superstar, Laura Ingraham, was mocking the Ukrainian president’s plea for peace: "We had kind of a really pathetic display from the Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, earlier today... where he in Russian… he was essentially imploring Vladimir Putin not to invade his country."

Beyond the halls of Rupert Murdoch’s news empire, in Florida, a conservative conference hosted by Nick Fuentes—arguably the most powerful activist when it comes to mobilizing the Republican base—asked the crowd, "Can we get a round of applause for Russia?" The applause was accompanied by chants of "Putin! Putin!" On Telegram, Fuentes called the invasion "the coolest thing to happen since 1/6," a reference to the 2021 terror attacks in Washington, DC, designed to overthrow the results of the 2020 election.

Conservative commentator Candace Owens was blaming the US and NATO, while at the same time urging American military action against… Canada. "STOP talking about Russia," she urged, and "send American troops to Canada to deal with the tyrannical reign of Justin Trudeau." Because asking people to protect themselves and others is evil on a far greater scale than launching missiles against civilian targets.

Right-wing media were not the only ones sneering at Ukraine and cheering on the autocrat. Politicians on both sides of the Atlantic also continued to play their part in the disinformation effort.

In the UK’s Conservative Home publication, Tory peer Lord Hannan of Kingsclere was writing his own love letter to despotism: "Vladimir Putin has won. He has placed himself at the centre of world affairs, strengthened his alliance with China, cowed his neighbors and solidified his domestic support. He has divided his rivals, sundering Europe from the Anglosphere—or, more precisely, separating Germany from the other democratic powers. Best of all, he has shown the West to be dithering, divided and drippy."

On the other side of the Atlantic, Senate candidate and Trump loyalist J.D. Vance said on a podcast that "I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or another," and tweeted that "our leaders care more about Ukraine’s border than they do our own." Another Republican lawmaker chimed in to claim: "Zelenskyy is a globalist puppet for Soros and the Clintons."

And of course, Trump himself was full of praise for his Russian friend and ally: "I went in yesterday and there was a television screen, and I said 'This is genius,'" the GOP leader said of the invasion. "Putin declares a big portion of the Ukraine, of Ukraine, Putin declares it as independent. Oh, that's wonderful."

A few days later, speaking at a Republican conference in Orlando, he underscored whose side he was (still) on: "The problem is not that Putin is smart—which, of course he’s smart—but the real problem is that our leaders are dumb. Dumb. So dumb." He added that Putin was "playing Biden like a drum and it’s not a pretty thing to watch."

Never in my lifetime have so many been proven so wrong in so short a time.

Yet not a single Republican of any stature has spoken out to denounce Trump’s rhetoric. Mitt Romney came perhaps the closest when he told CNN: "How anybody in this country, which loves freedom, can side with Vladimir Putin, who is an oppressor, a dictator, he kills people, he imprisons his political opponents, he has been an adversary of America at every chance he’s had, it’s unthinkable to me. It’s almost treasonous." But even Romney was apparently too afraid to identify his party’s leader by name.

Meanwhile, a Fox News poll found that Republicans continue to hold a more negative view of President Biden than they do of Putin. And a Yahoo!/YouGov survey found that just 3% of Trump supporters are willing to say Biden is "doing a better job leading his country" than Putin, while nearly 47% prefer Putin, who has led his nation to economic collapse, military humiliation, and global isolation. This is what "Trump derangement syndrome" looks like, ladies and gentlemen.

All of which might suggest that disinformation continues to exert its hold over the American political scene. Except for what was happening throughout the rest of the world.

What real leadership looks like

With Russian troops advancing into Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the Ukrainian president dismissed just days earlier by Laura Ingraham as "pathetic," appeared in olive green military-style garb against the backdrop of his office, one of Kyiv’s most recognizable structures, to record a selfie-style video during which he responded to Russian disinformation claiming that he had fled the country.

"I am here," he told a global audience. "We will not lay down any weapons. We will defend our state, because our weapons are our truth…. A lot of fake information has appeared on the internet saying that I allegedly called on our army to lay down its arms and that evacuation is underway. Our truth is that this is our land, our country, our children and we will protect all of this."

He further demonstrated his talent for a brave and pithy soundbite a few hours later when he was offered a flight to safety by the US military. His response: "I need ammunition, not a ride."

The next day, he spoke directly to his Russian neighbors, in their own language, in an address The New Statesman’s Jeremy Cliffe said "showed much more respect for the Russian people’s capacity for decency and intelligence than Putin has ever done."

Said Zelenskyy: "Lots of you have relatives in Ukraine, you studied at Ukrainian universities, you have Ukrainian friends. You know our character, our principles, what matters to us… The people of Ukraine want peace… You are told we hate Russian culture. How can one hate a culture? Neighbors always enrich each other culturally. But that does not make them a single whole. It does not dissolve us into you. We are different, but that is not a reason to be enemies."

Having been derided as a clown because he had been one of Ukraine’s best-known comedians before running for office, he demonstrated that his previous roles had prepared him for life in front of the camera during much more difficult circumstances. The imagery around Zelesnkyy has been extraordinarily powerful—he seems to be the only politician who can be photographed in military garb without looking like an imposter—while the imagery projected by Putin has been spectacularly self-defeating, as Washington Post columnist Jennifer Rubin explained.

"Russian President Vladimir Putin on Sunday sat yards away from his advisers in his marble fortress. He seemed both unhinged and diminished, a menacing, soulless figure dwarfed by a giant table.

"We also witnessed the polar opposite sort of leader in the gritty, heroic Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, out on the streets of Kyiv with his people and defying pleas for his safety…. We have the perfect distillation of good and evil. Freedom and repression. Kindness and cruelty. The authoritarians don’t look ‘smart’ or strong; they look scared and befuddled."

Meanwhile, the world was seeing images of ordinary Ukrainians, many of whom matched—or surpassed—their president in fortitude: a small group of soldiers on a lonely island telling a superior Russian force on a warship to "go fuck yourselves"; an elderly woman presenting the young invaders with sunflower seeds so that the national emblem might grow where their bodies fall; a man with a cigarette dangling from his lip carrying a mine out of the path of advancing Ukrainian troops.

The nature of war is such that some of the stories we see in our Twitter feeds and even on the nightly news may turn out to be exaggerated or false, but taken together these stories created a narrative about the war that overwhelmed the unconvincing propaganda coming from Russia and its Western allies. They had a powerful emotional impact and turned the tide of global public opinion against the invaders.

The individual stories were supplemented by some extraordinarily savvy public relations moves by the Ukrainian leadership. The government announced that it was setting up a hotline so that the mothers of Russian soldiers could call to find out whether their sons were dead or captured. Many of those captured were allowed to call home to reassure loved ones that they were still alive—in some cases, it appeared to be the first time parents discovered that their sons were on the front lines of a war.

Ukrainian officials have also published dozens of videos featuring captured Russian soldiers to the Telegram channel Find Your Own, established by Ukraine’s interior ministry. In one, a visibly wounded soldier identifies himself as the commander of a sniper unit based in the Rostov region. The Guardian was able to track down his sister in Russia, who said: "I knew Leonid was in the military, but I had no idea that he was sent to Ukraine. I was completely shocked. I had no idea that he was fighting in there."

The contrast between the compassionate approach of Ukraine and the ruthless onslaught of Russian missiles striking civilian targets could not have communicated more clearly that this is a struggle between good and evil—perhaps more clearly so than any conflict since the Second World War.

(At this point, it would be wrong not to acknowledge the role that race has played in perceptions of this war. Many television commentators have revealed their own biases by comparing the European refugees of this conflict to the brown and black-skinned victims of other wars around the world, by finding far greater compassion for fellow-Europeans, fellow white Europeans, than they were ever able to muster for refugees from Africa or Asia or Latin America. Hopefully, this will prompt some self-reflection and more empathy in coverage of future wars.)

Says Boot in his Washington Post column: "Public opinion matters. It moves politicians in democracies. We are now seeing the West take far sterner measures against Russia—including kicking Russian banks out of the SWIFT system of interbank transfers and, perhaps even more significantly, sanctioning Russia’s central bank—than was conceivable even a week ago."

Facts can win

It is more than 300 years since Jonathan Swift observed that "falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it." It is more than 100 years since Mark Twain was credited with his own version of the same aphorism: "A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots."

In recent years, it has been increasingly easy to despair at the possibility that mere facts can ever triumph over disinformation. But as disinformation expert Molly McKew observed, disinformation tactics do "begin to fail when light is thrown onto how they work and what they aim to achieve." And that light is suddenly very powerful.

Earlier this week Ben Collins, a senior reporter for NBC News, began a Twitter thread by posting a photograph of Vladimir Bondarenko, a blogger from Kyiv who "really hates the Ukrainian government." But according to Facebook, and Collins, "he also doesn’t exist…. He’s an invention of a Russian troll farm targeting Ukraine. His face was made by AI."

Sure enough, if you look closely at Bondarenko’s otherwise unremarkable face, you start to notice some inconsistencies, especially with the ears, which are apparently really difficult to fake. The ruse is even more obvious when you look closely at Irina Kerimova from Kharkiv, a "private guitar teacher" until she became editor-in-chief of a Russian propaganda website in 2017. Neither the ears nor the earrings match this time.

The two profiles were tied to Ukraine Today, a Russian propaganda operation created to make Ukraine look like a failed state. Ukraine Today in turn is tied to News Front and South Front, two Russian propaganda outfits identified in a 2020 report by the State Department that, if anything, went even more under-reported than the Mueller findings. That report delved into a St Petersburg "troll farm," which, after Mueller, transformed into USA Really.

Collins even posted a useful color-coded map in which USA Really (financed by Russian oligarch Yevgeniy Prigozhin) planned to target each state: purple for 2nd Amendment issues; green for poverty; dark brown for taxes; navy blue for racial issues; light blue for crime; and so on. The map was first posted in 2018. The disinformation networks responsible for all this were finally taken down by Facebook and Twitter this weekend.

At NBC’s website, Collins wrote that Facebook said it had taken down 40 profiles tied to the disinformation operation, profiles that were a small part of a larger persona-building operation that spread across Twitter, Instagram, Telegram, and Russian social networks. Twitter, meanwhile, said it had banned more than a dozen accounts tied to the News Front and South Front operation.

Later, a YouTube spokesperson, said the company has taken down a series of channels tied to a Russian influence operation, while Facebook said it took down a separate multipronged disinformation operation by a hacking group based out of Belarus. The company said it hacked social media accounts to use them to spread pro-Russian propaganda.

According to Collins, "The hackers targeted journalists, military personnel and local public officials in Ukraine, using compromised email accounts and passwords to log into their Facebook profiles. The hacked accounts would then post a video of what they said was a Ukrainian waving a white flag of surrender."

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said on Sunday that she planned to "ban in the EU the Kremlin’s media machine," and that the EU was "developing tools to ban their toxic and harmful disinformation in Europe." The Financial Times, meanwhile, reported that European internal markets commissioner Thierry Breton urged Google chief executive Sundar Pichai and YouTube’s Susan Wojcicki to ensure "war propaganda" never appears as "recommended," and that the prime ministers of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland had signed a joint letter directed to the heads of Meta, Google, YouTube and Twitter demanding a clampdown on Russian state media on their platforms.

Suddenly, previously intransigent social media platforms and technology companies were prepared to take a side. Facebook and short-form video platform TikTok both announced that they would block access to Kremlin-backed news sources Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik in the EU following a request from Von der Leyen. Despite accusations of censorship from Russia (which also began restricting access to Facebook after its own citizens began using the site to organize protests) Microsoft on Monday said it had blocked downloads of the RT app on its Windows app store worldwide, as well as blocking RT and Sputnik content from its MSN website.

In the US, meanwhile, Senator Mark Warner, chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, wrote his own letters to Facebook and Google, as well as Twitter, TikTok and Telegram, calling on them to "assume a heightened posture towards the exploitation" of their platform for disinformation operations. Perhaps it will become increasingly difficult to justify spreading disinformation in the US when it is blocked elsewhere in the world.

Inside Russia, meanwhile, the Kremlin’s tight control over the media was beginning to look less absolute.

On February 26, as Russia’s invading army was beginning to meet heavy resistance, the state online news agency Ria Novosti was telling Russians: "A new world is being born before our eyes. Russia’s military operation in Ukraine has ushered in a new era… Russia is restoring its unity—the tragedy of 1991, this terrible catastrophe in our history, has been overcome…. There will be no more Ukraine, as the anti-Russia."

Even to Russians—those with access to the internet of friends in the West—this spin on the news seemed utterly disconnected from reality, almost as if it had been written well ahead of time and somebody had forgotten to check in on the real world before the story was posted.

As The Economist reported, its tone appropriately bemused, on Russian television: "the Russian army is calmly fulfilling the task set by its commander-in-chief, demilitarizing and ‘de-Nazifying’ Ukraine; it has destroyed 1,067 military targets; Ukrainian soldiers are surrendering but are treated with great respect and care…. Grateful Ukrainians are welcoming Russian troops."

But those phone calls from captured Russian soldiers are getting through, and the Russian propaganda machine is "struggling to keep reality at bay," in part because—as the Ria Novosti article suggests—it wasn’t supposed to go like this. The Kremlin had done nothing to prepare the Russian public for a war.

"It is hard for those who don’t know the details to make out what is happening," Russia’s state-run Channel One told its audience. It is far better to rely on information from official sources, rather than fake videos on social media channels. "Those who spread such lies want to hold the world in their hands and people in fear."

The truth is breaking through, however. The complete collapse of the ruble sent shockwaves throughout the country; Russian companies and their employees are unable to ignore the fact that they have been completely cut off from global commerce; global horror at Russia’s actions has spread to Russia, with people—particularly young people—pouring into the streets to add their own voices to the protests taking place in European capitals. There are signs that the bravery of those willing to stand up to the government is contagious.

And independent Russian television channels like TV Rain and radio stations like Ekho Moskvy are still broadcasting. Novaya Gazeta, one of Russia’s last independent newspapers, is, The Economist says, "publishing stories about soldiers who had little idea where they were being sent."

Individuals outside the country found ingenious ways around Russia’s largely closed information system too. Anonymous, the international hacking group, launched denial-of-service attacks on Russian state media and posted a message on many of them: "Dear citizens. We call on you to stop this madness. Don’t send your sons and husbands to die. It is time to act—come out on the streets!"

Others were using Google Maps to find restaurants in various Russian cities, and then using the reviews option to leave messages that told the Russian people what was really going on in Ukraine. The Twitter account @YourAnonNews even provided Russian text, which translated as: "The food was great! Unfortunately, Putin spoiled our appetites by invading Ukraine. Stand up to your dictator, stop killing innocent people! Your government is lying to you. Get up!"

A world united

An almost unremarked aspect of President Biden’s leadership during this crisis (indeed, it has predictably attracted criticism) is its generosity: he has been happy to take the initiative when necessary, but equally happy to allow the EU to be out front when appropriate.

As a result, leadership has come from everywhere, including some surprising sources: Germany, with a new chancellor who many thought would stymie NATO’s response, was actually the first to respond to Putin’s aggression, canceling the Nord Stream 2 pipeline; the European Union, which Putin had sought to weaken through Brexit, moved quickly and efficiently to implement punishing sanctions; Switzerland, a bastion of neutrality, adopted the EU’s sanctions; even the UK appears to be contemplating real action against its resident oligarchs.

Of course, Russia’s Goliath could still trample the David of Ukraine, but the victory will come at a price Putin could not have imagined. Every one of his assumptions was wrong:

- He thought the US was weak and divided, but President Biden refused to allow domestic opposition to prevent him acting with integrity and resolve;

- He thought there were divisions within NATO, but the alliance came together quickly and unanimously;

- He thought Brexit had weakened the EU, but instead it strengthened the Union, making swift and decisive action easier;

- He thought sanctions would be mild—if they arrived at all—but they are unprecedented and are already having a devastating impact on the Russian economy;

- And, of course, he thought Ukraine would fall within hours, and its resistance has continued for weeks.

At the center of all of this is the disinformation campaign that Russia has waged for a decade. It won some victories, it sowed some chaos, but it failed in its primary objective. And now it has been exposed, its agents in the US and the UK are in plain sight, and its limitations are apparent. Reality may not be as speedy as a lie, but it is inexorable.

Of course, two years ago I believed that a global pandemic would bring people together and restore our faith in science and reason. It did the opposite.

The victories earned over the past several weeks could easily be reversed. It is inconceivable that the sanctions of Russia could survive a second Trump victory in two years, and that would likely lead also to the dissolution of NATO. But Trump’s true allegiance is no longer a matter of conjecture, and it would be nice to think that that will preclude the worst-case scenarios.

And it is, of course, also possible that given the humiliations of the past several weeks, and the imposition of a massive economic burden on Russian people, Vladimir Putin might not even survive long enough to see his puppet restored. Domestic opposition—including some of the oligarchs who wield enormous influence in Moscow—is on the rise.

Victory in the war against disinformation is by no means assured (and PR people have a critical role to play in that victory—again, more to come on that topic) but at least the events since late February have opened our eyes and shown us that leaders of courage and integrity and empathy are capable of fighting back.