Fifty years ago this month, Loretta Lynn released a song inspired by her childhood in Butcher Holler, Kentucky. Now she is the undisputed “Queen of Country Music."

-

October 2020

Volume65Issue6

Editor's Note: Holley Snaith is a historical researcher who has worked at the Nixon Foundation and Eleanor Roosevelt Center. Photos courtesy of Loretta Lynn Enterprises unless otherwise noted.

“Well I was borned a coal miner’s daughter.

In a cabin, on a hill in Butcher Holler.

We were poor but we had love.

That’s the one thing my daddy made sure of.

He shoveled coal to make a poor man’s dollar.”

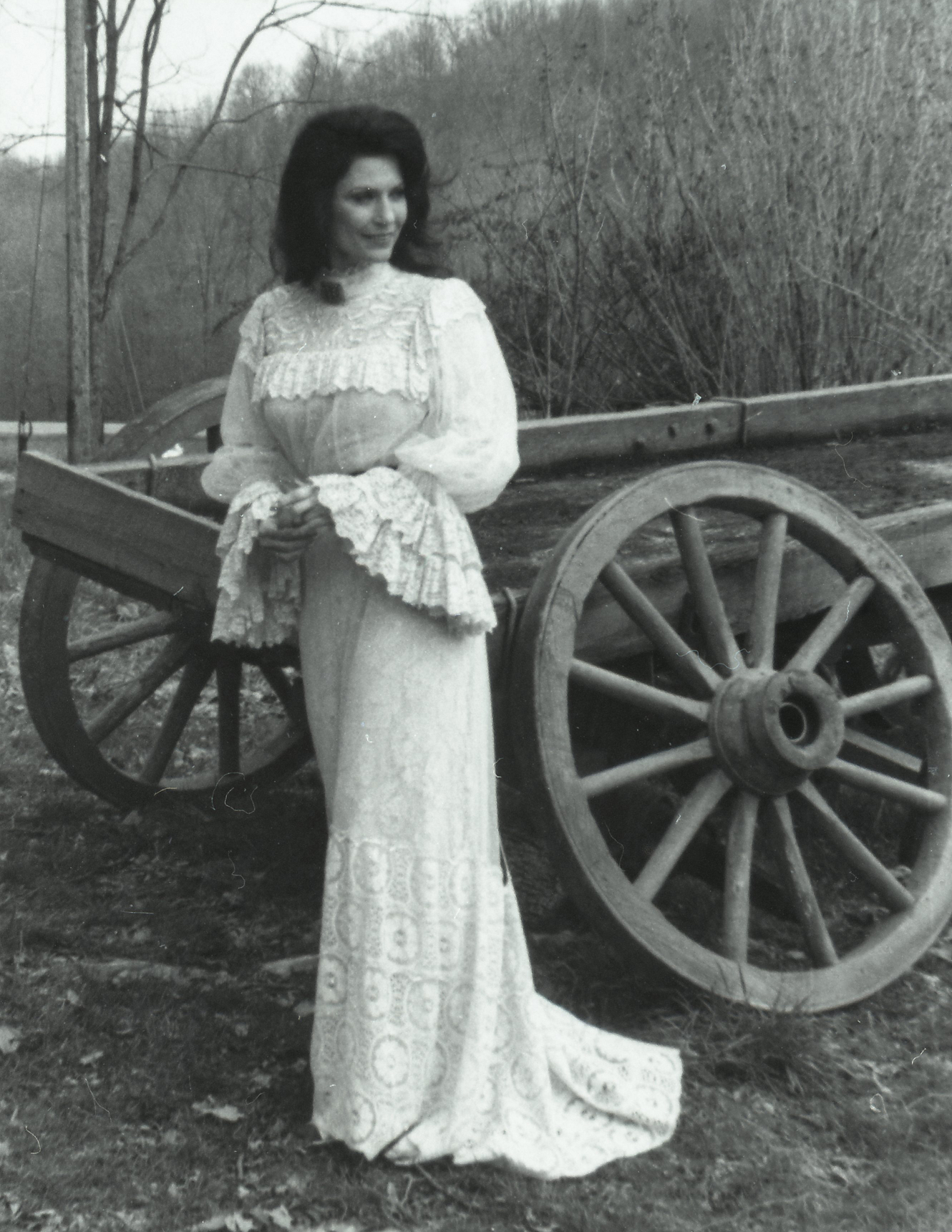

“Coal Miner’s Daughter” has become one of the most revered and recognized songs in country music, its words true Americana. This October marks fifty years since Loretta Lynn released her autobiographical tune, the song she will forever be associated with, the one fans holler for her to sing before her shows even begin.

Yet it is also Lynn’s most meaningful song. “It’s her favorite because she wrote it from the heart,” said Tim Cobb, Lynn’s longtime assistant and dressmaker, during a recent interview in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. “You can’t escape from that.”

Surprisingly, when thirty-seven-year-old Loretta Lynn sat down and began writing “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” it wasn’t meant to be hers. She had been asked to compose a song for a bluegrass act called the Osborne Brothers, appearing on The Wilburn Brothers Show, a weekly television program starring Doyle and Teddy Wilburn that Lynn also performed on. She began writing the song in typical bluegrass style, but it soon became clear that it was going in an entirely different direction.

Like many songwriters, Lynn writes about what is on her mind, and that day she was reminiscing over her childhood growing up in Butcher Holler, Kentucky, where bluegrass music was a tradition. It was after she completed that first verse that she realized this song was not meant for the Osborne Brothers; it was meant for her. By the end of the day, she had written nine verses.

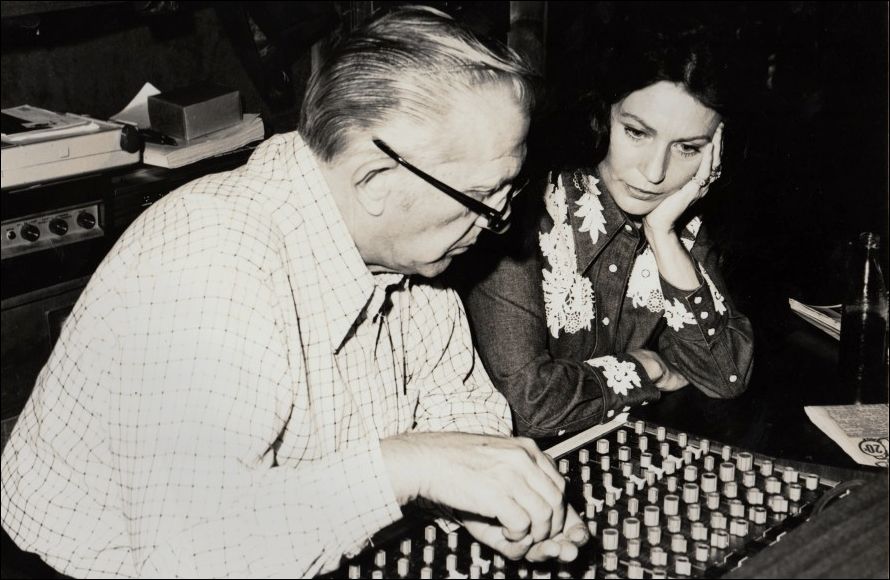

Lynn's producer at Decca Records, Owen Bradley, told her no one would want to listen to such a long song. So, she sat down and carefully removed three verses, an arduous task for a songwriter. Even with the song trimmed down, Bradley thought little of the tune, but he agreed to let Lynn record it out at his famous Bradley’s Barn in Nashville. She dictated the session, telling the steel guitar player and the fiddler where to come in.

Then she sang. No rhythm guitar, just raw vocals. After just a couple of takes, it was over. “Coal Miner’s Daughter” was released as a single on October 5, 1970 and steadily climbed the Billboard charts.

At the time, Lynn could never have guessed that the seemingly simple song reflecting on her poor but happy childhood would become her signature number, or that she would have a New York Times bestselling book out by the same name, and finally, a blockbuster movie that engrained her rags-to-riches story in pop culture. All she hoped to do was share her experience growing up as the daughter of two hard-working people who would go to the ends of the earth to ensure food was on the table.

“It is such an important song,” said Loretta’s granddaughter Tayla Lynn, also a singer, during an interview at her music venue in Waverly, Tennessee. “It tells the story of her life. Her deep love of her family, of her father, of her mother, and how she never got away from those roots.” For Loretta Lynn, the road from Butcher Holler to the top of the Billboard charts was a long, hard one, but throughout the whole journey, those roots remained with her every step of the way.

As a girl, Loretta Webb never gave much thought to the idea of leaving her family homestead in Butcher Holler. Born the second of eight children to Ted and Clara Webb on April 14, 1932 in a one-room cabin, Loretta’s childhood was filled with the sounds of laughter coming from children running up and down the “holler,” or hollow, one of the deep mountain valleys that ran throughout the Appalachian landscape and gave her hometown its name. Singing was a favorite pastime; the family would often gather on the front porch with their wood instruments and sing “hill” music.

Saturday nights were special for the Webb children, the only night of the week their daddy would turn on the Philco radio and tune in to the family’s favorite program: The Grand Ole Opry. Although the radio broadcast was permeated with static, Loretta always knew the deep, baritone voice of Ernest Tubb. When he would serenade the audience with his melancholy song, “Rainbow at Midnight,” young Loretta often cried. She would pull herself together after her mother threatened to turn the radio off if she didn't quit.

Every Sunday, the family trekked down to the local church to hear Elzie Banks give fiery sermons on salvation and eternal damnation. It was at church where the little girl with brown curly hair gained her affinity for singing. Back at home, Loretta serenaded her younger siblings while rocking them to sleep on the front porch swing. Her young voice possessed so much gusto that her daddy would yell at her to stop singing because everyone could hear her. She kept singing anyway.

Despite the comforts of hearth and home, there was no denying the fact that the Webb family was poor. In Butcher Holler, there was little difference between life during the Depression and life during economic prosperity. Ted Webb had a series of jobs, including one with the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, before taking a job with the Consolidation Coal Company in nearby Van Lear.

Eventually, the harsh life in the coal mines caught up with Ted. Already plagued by migraine headaches, something his daughter would come to inherit, black lung led to his subsequent premature retirement.

Clara Webb, a petite woman with a joyous personality, was the glue that held the family together. She took care of her husband and children, hunted and cooked dinner, and tirelessly scrubbed clothes on the washboard, often resulting in her fingers bleeding. In the wintertime, there were never presents bursting from underneath the Christmas tree.

One Christmas, Clara told her children that Santa could not make it out to the cabin because the snow was too deep. In an attempt to assuage the children’s dismay, she drew a checkerboard and used white and yellow corn for checkers.

As a teenager, Loretta spent little time thinking about her future. In her mind, she would grow up, get married, have a couple of babies, and eventually die in Butcher Holler. This all changed when she met a twenty-one-year-old local boy named Oliver Vanetta Lynn, Jr., better known as “Mooney,” a nickname he earned because he ran moonshine.

Mooney was just out of the army, having served in the European theater in World War II, when he became fixated upon the fifteen-year-old Loretta. At a pie social in December 1947, he made a bid on Loretta’s chocolate pie and won. The prize was walking the girl home. When Loretta arrived back at the cabin, she knew she was in love. The young pair casually courted for a month. He drove his Jeep up the steep holler, and the bewildered Webb children watched in amazement because they had never seen a vehicle before.

In January of 1948, a smitten Mooney asked Loretta to marry him. She said yes. Ted and Clara Webb were not thrilled with the idea of their naive teenage daughter marrying an older man who had a reputation for being wild, but they concluded that trying to prevent the union would only make matters worse. On a cold and rainy day in January, Loretta Webb married Oliver V. Lynn, Jr. Before the wedding, Loretta’s mother told her she would cry a tear for every drop of rain that fell. Although the premonition would prove to be correct, no one could foretell that, one day, Loretta would take those tears and turn them into hit songs.

Although Loretta was not aware of just how financially poor her family was, she knew the world had more to offer. She loved flipping through the Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog and admiring the beautiful clothes she one day hoped to own. After she married Mooney, it was her expectation that they would settle down, have a nice home, and buy some of those nice clothes. That turned out to be a pipe dream.

The marriage started off tumultuous, and within a few months, the young couple briefly separated. Both cited different reasons; Mooney claimed it was because Loretta was a poor cook, Loretta said it was because of another woman. But after they reunited, Loretta was shocked to hear from her husband that the two of them would be moving across the country to Washington state, as far away from home as she could possibly get. Mooney had lived out west as a boy and relished the country air. Besides, he himself was anxious to get out of the Kentucky coal mines. He left his wife at home while he ventured out to find a job.

After being hired by Bob and Clyde Green to work as a farmhand, he sent for her. Sixteen-year-old Loretta boarded a train for the first time, crying as she hugged her father goodbye, and set off for a new life on the West Coast. She was seven months pregnant and filled with mixed emotions: sadness at leaving the family she had never left before, but excited for the life she was going to create with her own family.

As a child in Butcher Holler, Loretta learned from Ted and Clara how to survive with what you have, no matter how little that may be. That strength she garnered during childhood was never more needed than when she was a young wife and mother in Custer, Washington.

By 1955, Loretta was twenty-three years old, had been married for seven years, and was the mother of two boys and two girls. Mooney continued to farm the land for Bob and Clyde Green, while Loretta cleaned the Green’s house and cooked for thirty-six ranch hands.

Once the Lynn family moved to a home with enough land for a garden, she began canning vegetables. The first year she entered the Washington State Fair, she picked-up an impressive seventeen first prize ribbons. Probing for ways to make extra money, Loretta began picking strawberries out in the fields, taking her small children out with her. Although the work was hard, it gave her something she had never had before: her own source of income.

While the 1950s brought economic growth, that was not the case for Loretta and her family. It seemed as though little had changed since those days in Butcher Holler. The relationship between Mooney and Loretta continued to be rocky; he still drank too much and had a roving eye. Mooney was not easy to handle when he was drinking, but Loretta stood her ground and gave just as good as she got. Even with her inherited strength, her husband’s ways were hard for Loretta to accept because, through it all, she loved him.

There was little time for Loretta to contemplate her heartaches because she was simply trying to survive and feed her children. One arduous day while Mooney was gone for a few weeks on a logging job, Loretta decided she was sick of eating boiled dandelion greens, so she snatched her husband’s broken .22 rifle and killed a pheasant across the pond on her first shot. Having never learned how to swim, she carefully waded across the pond to seize her family’s dinner.

Back at their meager home, Loretta spent her days washing her family’s clothes on the washboard just as her mother did in Butcher Holler; now it was her fingers that were bleeding. Those pretty clothes in the Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog that Loretta daydreamed about for herself and her children remained a fantasy. But these monetary woes would soon disappear, thanks to a natural talent, a bold dream, and a heap of determination.

Despite his shortcomings as a husband, it was Mooney Lynn who noticed that his young wife had a gift for singing. He would hear her singing to the children at night as she put them to bed, though she only knew a couple of songs all the way through. She was dumbfounded when Mooney came home with a seventeen-dollar Sears, Roebuck & Co. guitar and informed his wife she was going to learn to not only play the guitar but also write songs and sing. Loretta had only an eighth-grade education and was painfully shy; could she really do this? It was Mooney’s faith in her ability that motivated her to at least try, so she spent hours listening to her idol Kitty Wells and poring over Country Song Roundup in an attempt to master writing.

For Loretta, writing came more naturally than singing. As a little girl in Butcher Holler, she would swiftly think up songs using words that rhymed. Now she was performing for a small audience consisting of her four young children. She lined them up from oldest to youngest and asked if they thought she could sing. Loretta would smile as all four nodded in encouragement.

Before she was ready, Mooney told Loretta that it was time she started performing in public. So, on a Wednesday night in 1959, Mooney and a reluctant Loretta arrived at the home of brothers John and Marshall Penn, who were part of a group called The Westerneers.

Loretta knew nothing about different keys, but she told the boys to play the Patsy Cline hit song “There He Goes.” The next morning, she booked her first singing engagement, performing at the Delta Grange Hall on Saturday night with the Penn Brothers for five dollars. Although the paltry fee would be meaningless to singers today, for Loretta, it felt like she had made it to the big time. Gradually she saved up enough money to buy herself a Western outfit consisting of a fringed black skirt, white cowboy hat, a blouse with small roses embroidered on it, and some snazzy cowboy boots.

With this newfound look came confidence. When she first began singing, Loretta would only stare down at her feet, afraid to look the audience in the eye and read their response. She had been told by one drunken barfly that there was only one Kitty Wells and she should just hang it up. But people continued to show up to hear her sing. After a few months, Mooney decided it was time for Loretta to put her own band together, so she recruited her musical brother Jay Lee Webb to play lead guitar and another friend, Roland Smiley, joined on steel. The group, called Loretta’s Trail Blazers, was hired as regulars at Bill’s Tavern in nearby Blaine.

Mooney persisted in making his wife a well-recognized singer, so when he heard about an opportunity to appear on fellow country singer Buck Owens’ television show the BAR-K Jamboree in Tacoma, he grabbed his wife and they jumped in the car. At this time, Loretta was discovering her passion for writing. Her first song was inspired by a sad young wife recently jilted by her husband that Loretta had met in one of the taverns she was performing at. Soon after, while at home picking her guitar leaning against the outhouse, Loretta wrote “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl.” Her second song, “Whispering Sea,” came to her as she and Mooney were out drifting in the sea on a fishing excursion.

Up in Canada, a man by the name of Norm Burley was watching the Jamboree and was moved to tears by the young woman in the Western outfit singing “Whispering Sea.” It reminded him of his late wife and the dark nights he yearned for her while staring out at the sea. Burley was so impressed he informed Loretta and Mooney that he wanted Loretta to record on his small label, Zero Records. In February 1960, Loretta and Mooney headed south to Los Angeles to record her songs, all expenses paid by Burley. The couple went from studio to studio with Burley’s money, searching for anyone willing to record the aspiring singer. Finally, renowned producer Speedy West agreed to record her. After recruiting some skilled pickers, West recorded “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl” and “Whispering Sea” in one day.

Once Zero received the records, it was time to distribute them. Unfortunately, neither Burley nor the Lynns knew much about promoting a record. Mooney snapped a quick picture of Loretta, using a bedspread as a backdrop, and wrote a short biography of his wife to send with the record to every radio station he could find.

Wanting to do more to help, Burley offered to pay for a promotional trip across the country. The Lynns packed their old Mercury, and the family of six headed down the West Coast, stopping at every radio station along the way. The curly-haired, youthful Loretta would walk in, introduce herself, and ask the disc jockey to play her record. From there, they headed east and left two of their children with Mooney’s parents, and the other two with Loretta’s widowed mother. Then it was on to Nashville. The journey was long; the couple slept in the car, they lived on baloney sandwiches and watermelon that Loretta would discreetly steal, and she only had one dress to wear. Still, Loretta found herself beginning to enjoy the business, and she had earned the respect of her determined husband. For the first time in their twelve-year marriage, Loretta and Mooney were true partners.

One summer’s day, Loretta woke up in the backseat of her Mercury to find, to her astonishment, that she was outside the Mother Church of Country Music, Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. Ever since she had started singing in Washington, her dream was to stand on the Grand Ole Opry stage and perform. During that trip to Nashville, Loretta told disc jockeys along the way that she was going to Music City to perform on the Opry. They told her she was crazy, that it would take years for her to get on that prestigious stage. They underestimated Loretta Lynn, because on October 15, 1960, she made her first of many appearances on the Grand Ole Opry. She was introduced by her childhood hero, the man whose baritone voice made her cry: Ernest Tubb. Just two years later, on September 25, 1962, she officially became an Opry member. The coal miner’s daughter had arrived.

By the time the single “Coal Miner’s Daughter” was released in October 1970, Loretta Lynn had worked her way to the top of the charts and was one of the top female country artists. After establishing herself in Nashville and becoming acquainted with Doyle and Teddy Wilburn, Lynn cut a deal with their publishing company, Sure-Fire Music, and signed with Owen Bradley at Decca Records. She wrote and recorded a series of feisty hit songs such as “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin,’” “You Ain’t Woman Enough,” “Your Squaw is on the Warpath,” and “Fist City.”

When it comes to writing, Lynn’s chief inspiration has always been her own life, and each of these hits was somewhat inspired by her own troubled relationship with Mooney. Age had not changed her headstrong husband. He was her biggest supporter, but his demons continued to cause problems.

Financially, Lynn was thriving in the male-dominated industry. Being the first female in country music to become a millionaire, she could now afford those clothes from the Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog for her now six children, and she no longer scrubbed them on a washboard. That six-room cabin in Butcher Holler her family moved into when she was eleven paled in comparison to the picturesque antebellum home that she and Mooney purchased in a small town called Hurricane Mills, Tennessee, the town in which Lynn still owns and lives in. Lynn’s fan club burgeoned, her concerts sold out, and she finally bought her own luxurious tour bus.

“Coal Miner’s Daughter” solidified Lynn’s image as the quintessential writer. She proved that she could write about anything, from fighting with another woman, crying over a lost love, and even longing for a bygone childhood. Producer Owen Bradley was so impressed by his profitable artist that he dubbed her “the female Hank Williams.” A few months after the song’s release, Lynn proved her loyalty to her roots by arranging a large benefit for the families of the thirty-eight miners who died in the Hurricane Creek mining disaster in December 1970, one of the deadliest mining disasters in this nation’s history.

As she stood onstage and began singing “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” the memories of her father exiting the mines, covered in coal dust and sometimes with a bloody nose, began to swirl in her mind. Ted Webb died in 1959, just before his daughter began singing professionally, but his influence on his eldest daughter remained ever-present. She smiled because she was proud to be a coal miner’s daughter, but the tears fell freely because she related to the families in the crowd.

Riding on the coattails of the song’s success, Lynn penned an autobiography by the same title, and Coal Miner’s Daughter went on to become a 1976 New York Times bestseller. Lynn’s legacy was cemented in cinematic history in 1980 when the movie Coal Miner’s Daughter, starring Sissy Spacek and Tommy Lee Jones, was released, earning Spacek a “Best Actress” Oscar.

The triumphant decade ended with Lynn being named the Academy of Country Music’s “Artist of the Decade,” the only female to ever receive the honor. What made the honor even more special was the fact that Lynn’s mother, Clara, presented her daughter with the plaque, alongside Lynn’s youngest sister, Crystal Gayle, herself a rising country and pop singer. Lynn lost her beloved “mommy” the next year.

The awards kept coming and the fans turned out in droves, but the fame only made Lynn’s life more complex. Throughout her career, she has been hospitalized countless times for exhaustion, nervous breakdowns, migraines, ulcers, and more. She also had to sacrifice time with her family, spending months at a time on the road. The plantation home in Hurricane Mills that she and Mooney purchased in 1967 was never her home; the bus was. Lynn has also experienced her share of despair. She has lived through the agony of losing her two oldest children, her four brothers, and numerous friends.

In 1996, Mooney Lynn died at the age of sixty-nine after a long battle with diabetes. For six years, Lynn had never left his side. Their relationship was complex and far from idyllic, but the two had an indestructible bond that could only be held together by love. Disconsolate after her husband’s death, Lynn questioned whether she could ever perform again without his stalwart support. Eventually, the flair for performing returned, and since then, she has released six albums. She and rocker Jack White picked up two Grammys for their album, Van Lear Rose, a title that pays tribute to her Kentucky roots.

In the fall of 2019, Lynn was honored with the Kris Kristofferson Lifetime Achievement Award presented by the Nashville Songwriters Association International (NSAI). NSAI asked Lynn’s granddaughter, Tayla, to open the ceremony with her grandmother’s staple song, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Tayla remembers being terrified as she began the song with no backup musicians, just her vocals. After the song ended, she walked over to her legendary grandmother, about to be escorted onto the stage by Tayla’s father, Lynn’s son Ernest Ray, and asked if her performance was okay. There on the stage at the beloved Ryman Auditorium, Lynn looked at her and said, “Honey, I thought that was me out there.” That night, Lynn’s two worlds, her family and career, which for so long had been at odds with one another, merged. This fall, Tayla will be releasing a Loretta Lynn tribute album; the family legacy is secure.

At eighty-eight years of age and celebrating sixty years in the music industry, Lynn has no plans to retire. The stroke that she suffered in 2017 and the broken hip in 2018 could not stop her from doing what she has loved for so many decades. In 2020, she released a memoir called Me & Patsy: Kickin’ Up Dust about her brief but life-changing friendship with the renowned Patsy Cline, as well as a re-recording of the Patsy Cline song that launched their friendship, “I Fall to Pieces.” In the spring of 2021, she will be re-releasing her bestselling book Coal Miner’s Daughter as well as a new album.

Loretta Lynn has indisputably earned the title the “Queen of Country Music.” The first female to be given the prized Entertainer of the Year award from the Country Music Association in 1972 is now the most awarded woman in country music.

Still, it is a moniker Lynn shies away from. Inside the Coal Miner’s Daughter Museum in Hurricane Mills, Tim Cobb, who is not only her longtime assistant but also arguably her closest friend, smiled and told me, “Loretta insists she’s just the ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter’.”