Excluded from mainstream white freemasonry, African Americans in the early U.S. founded a branch rooted in advocacy and the fight for civil rights.

-

October 2020

Volume65Issue6

The late-summer sun beamed down on the parade route in New York City, forcing most people to shed layers of clothing in order to stay cool and comfortable as they marched down the street. But being an honorable member of an ancient fraternal organization meant discipline and dedication, a fact embodied by the ornate, if weather-inappropriate, ceremonial regalia worn by one group of participants that sweltering afternoon.

Clad in suits with brass buttons, white gloves, Masonic aprons, and feathered hats, these marchers strolled along undeterred by the heat, proudly waving at onlookers as the procession flowed down Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard. They were freemasons, marching in the 50th annual African American Day Parade last year in Harlem.

“That’s right! Teach those boys how to be men!” exclaimed an onlooker as a group of well-heeled teenagers passed by, sandwiched between groups of their senior counterparts. The boys were members of the Knights of Pythagoras, a division of Freemasonry open to young African American men. And the marchers bookending the Knights were Prince Hall Freemasons and their female cohorts, the Sisters of the Eastern Star.

Mention Freemasonry, a fraternal organization that traces its roots to medieval stonemason guilds in Europe, and most people imagine a secretive culture with mysterious motives — something antiquated, out of touch, and insular. Since its members united to establish the first Grand Lodge in 1717, a panoply of accusations and conspiracy theories have been lobbed at the group. Claims range from the mundane (Freemasonic elected officials engaging in political manipulation), to the scandalous (Jack the Ripper was a Freemason), to the outrageous (Freemason astronauts faked the moon landing).

But there is another story of Freemasonry, one that has been overshadowed by the sensationalism surrounding the predominantly white, mainstream version. It is the story of Prince Hall Freemasonry, the parallel and internationally recognized African American branch of Masonry. It is the oldest African American fraternal organization in the United States, predating the Constitution and the election of the first president.

“It’s not just an organization,” said Kevin Wardally, treasurer of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge on 155th Street in Harlem. “It’s a sacred trust that was given to me by my grandfather, and my grandmother, to pass on to my son.”

Since its inception at the dawn of the Revolutionary War, Prince Hall Freemasonry has carried on a separate tradition from the mainstream order, one rooted in advocacy and the fight for civil rights. As the organization grew during the antebellum era, Prince Hall Lodges counted enslaved Black men and abolitionists amongst their members, yet remained largely unrecognized by mainstream Freemasonry. During the mid 20th century, Prince Hall Freemasonry again surged as a hub for activism, housing regional chapters of organizations instrumental to the Civil Rights Movement, such as the NAACP and the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC), within their Lodges.

Today Prince Hall Freemasonry continues to inspire African Americans to join its order. The organization operates internationally and counts over 300,000 men in its ranks, including families who have passed along membership through generations. One of the places the order continues to thrive is in New York, home to one of the oldest Prince Hall Lodges in the country.

A Freemason Grows In Harlem

“As an organization, we’ve always been dedicated to the betterment and upliftment of our people,” Wardally said at his Lodge during their annual Thanksgiving dinner last year, provided free of charge to neighbors and anyone in need.

Born and raised in Harlem, Wardally carried on a deeply valued family tradition when he joined the order a decade ago. Still, like many of his fellow members, his interest didn’t come naturally. Despite having relatives active in Prince Hall Freemasonry for decades, he spent years rebuffing his family’s encouragement to join the organization.

Instead, growing up in the 80s and 90s, he sought other means of embracing his identity as an African American. “It was a very radical time for Black thought,” Wardally, now 47, said. “And to me, the Masons always looked like a bunch of old guys were wearing aprons.”

What finally changed Wardally’s mind was a growing interest in history. In researching his heroes, men like Civil Rights leader A. Philip Randolph, Congressman Charles Rangel, and Southern Christian Leadership Conference leader Andrew Young, Wardally began to find a common thread — they were all Prince Hall Freemasons.

“As I started to study people I liked, and I cared about, all of them were here,” Wardally said.

As he continued to dig, he realized Prince Hall Freemasonry, including the Lodge his grandfather belonged to in Harlem, had advocated for the rights of African Americans since it began. James Varick, abolitionist and founding Bishop of the Mother Zion AME Church in Harlem, the oldest African-American church in New York City and a stop on the Underground Railroad, was a Prince Hall Mason. In the 20th century, activists and Civil Rights leaders — including Randolph, Wardally’s hero — gathered in the lobby of the same Prince Hall Grand Lodge to organize the March on Washington in 1963.

It was at that point that Wardally resolved to follow in the footsteps of his ancestors. “I made a decision that the way I was going to change the world, and my life, was through this organization,” he said.

A Short Primer On Freemasonry

The organization known as modern Freemasonry today is believed to have originated in the Medieval Era. During a time when European cities were scrambling to erect the cathedrals necessary to establish a throne for their Bishops, the strength of stonemason guilds and their members grew exponentially. As time moved on, these guilds morphed into lodges, whose members worked as trade-based masons.

In the aftermath of the Great Fire of London in 1616, hundreds of these masons found work rebuilding the city from its ashes. Eventually the need for operative masons waned, but the lodges remained. Over time they evolved into fraternal societies whose members began practicing a symbolic version of their craft, focused less on building physical environments and more on improving social ones, their immediate communities and society at large.

In 1717, four of these lodges gathered together to form the Grand Lodge of England, and modern Freemasonry was born with the mission to “take good men and make them better,” according to their motto. Open to individuals from any religion or social class, Freemasonry only accepted men of good moral character, deemed worthy enough to join the order. Members vetted prospective candidates, casting a closed ballot to determine whether or not the applicant was accepted. Each Lodge was run by a Grand Master, elected by his peers. The organization opposed recruitment, which meant current members often vouched for friends, and membership was passed along through families. The tools used by stonemasons also took on a symbolic meaning, evolving to represent the refinement of one’s character instead of instruments for physical construction. The phrase “on the level” is of masonic origin, implying a person, like a block of granite used to build a cathedral, is reliable and trustworthy. And as members of each Lodge also focused on supporting their larger communities, each chapter developed a different character, shaped by the individuals making up the group and by the needs of those around them. “Each Lodge always has its own personality,” said Dirk Hughes, director of the Masonic Museum and Library in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “It’s a reflection of its members.”

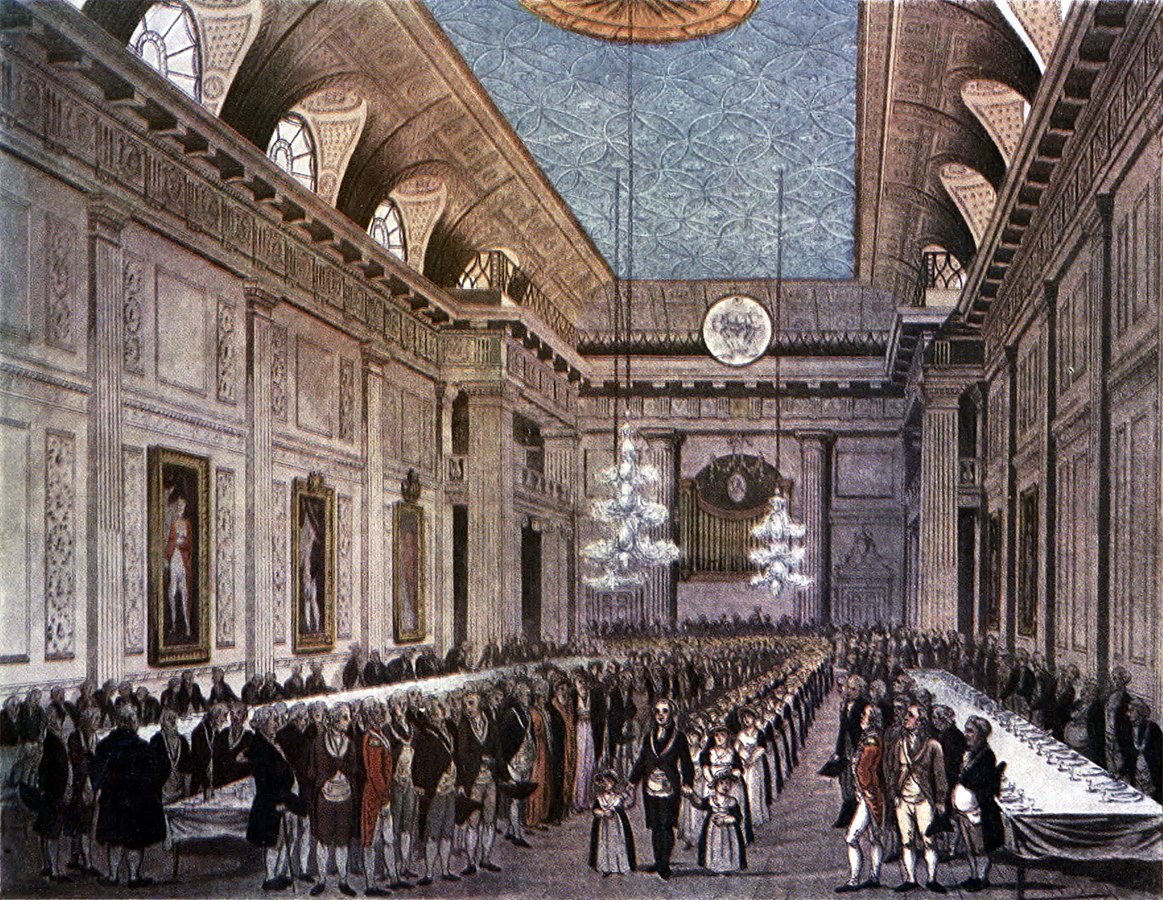

After Freemasonry emerged in London in 1717, the group continued to spread internationally. But it found particular popularity in colonial America, where the idea of a democratic brotherhood, one open to members regardless of their faith, class, or social standing, appealed to many men. The first lodge was founded in Boston in 1733, followed by other lodges in states like Pennsylvania and elsewhere in the colonies.

Freemasonry also promoted values of self-governance and reliance, attracting many of colonial America’s elite citizens. Some members of the organization were engaged in the fight for independence from Britain. At least eight of the fifty-six delegates who signed the Declaration of Independence were Freemasons, as were several important figures in the American Revolution, including Paul Revere and John Hancock. And when Americans elected George Washington as their first president, he had been an active member of Freemasonry for over 35 years.

Prince Hall Freemasonry, Born From A House Divided

As freemasons grew in popularity among white colonists, African Americans in early America took an interest in the order, too. The story of African American freemasonry began in 1775, when abolitionist Prince Hall and 14 other free Black men sought initiation into the all-white St. John’s Lodge in Boston. Hall, who owned his own leather shop and fought in the Revolutionary War, championed the scholastic rights of Black children in Boston as a means toward achieving equality. He viewed Freemasonry as another path toward racial parity, a way for his fellow free Black men to organize and push for their rights through education and activism.

Despite Freemasonic doctrine stating that all men are equal, the members of St. John’s Lodge rejected Prince Hall and his cohort. Undaunted, they sought international recognition from an older Lodge overseas. They successfully petitioned the Grand Lodge of Ireland, and on March 6, 1775, founded the African Lodge №1, today known as African Lodge 459.

“When he began to look at the way people were being treated in the Boston area, he saw the usefulness of Freemasonry, and how it brought men together of different diasporas to work towards a common goal,” Wardally said of Hall. “He sought that same sort of thing for his folks in order to push them forward socially and civically.”

From the start, the African Lodge no. 459 and other African American Lodges that followed in its footsteps faced adversity from the Grand Lodges governing each individual state. At the time, members of most stateside Grand Lodges rejected the international recognition granted by the Grand Lodge of Ireland, and the subsequent recognition granted by the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE). This meant that in the United States, African American lodges were considered illegitimate, or clandestine, by their fellow white lodges.

Freemasonry wasn’t the only fraternal organization during this time that kept African Americans out of its order. Blacks seeking membership to groups like the Odd Fellows, the Elks Lodge, and the Shriners faced the same discrimination as Prince Hall and were rejected on the basis of race, compelling them to create their own versions. The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (established in 1843) is one example, as is The Improved Benevolent Protective Order of Elks of the World (established in 1898).

Still, Prince Hall Freemasonry, as it came to be called in honor of its founder, was the highest-profile of these groups. And despite the lack of official recognition, its members continued to push forward in their quest for legitimacy of their Lodges and for their rights as African Americans.

“The Prince Hall organization became very independently recognized within the Black community,” said Christopher Hodapp, Masonic historian and author of several books on Freemasonry. “Very well respected within the Black community, and remains so to this day.”

Although Prince Hall and mainstream branches alike hold the betterment of both one’s self and community as a core value, working towards this goal can have a deeper resonance within African American communities.

When Prince Hall Freemasons Richard Allen and Absalom Jones were relegated to the back of the church where they worshipped in Philadelphia, the men left the congregation in protest and founded their own. The land Allen purchased in 1791 to build his church, the first African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, is the oldest piece of land continually owned by African Americans in the United States. Mother Bethel AME served as a stop on the Underground Railroad, which helped formerly enslaved people from Southern States escape to the North in pursuit of freedom.

Abolitionists working on the Underground Railroad “would pick up the slaves in North Carolina in a cove, and unload them in Philadelphia,” Crawford Wilson, Mother Bethel AME’s historian, explained. “And then they would come to Mother Bethel.”

Branching out, the AME church established congregations throughout the Union. Like its mother congregation in Philadelphia, other AME churches also served as stops on the Underground Railroad. Like Allen in Philadelphia and James Varick in New York, the pastors and congregants were often Prince Hall Masons. The church, along with the Prince Hall Lodges many of its members belonged to, developed into some of the few safe spaces for African Americans to assemble.

“The idea of organizing in any and all ways was appealing to free African Americans. Whether it was church-based, or Masonic-based,” said Harold Holzer, director of Hunter College’s Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute and a leading authority on the culture of the Civil War Era. “It was an order. It was a place. Black people couldn’t even meet without arousing suspicion and crackdowns.”

When hopes for abolishing slavery started to become a reality, President Abraham Lincoln, unable to imagine a United States where formerly enslaved people lived harmoniously side by side with white Americans, proposed emancipated Blacks be sent abroad to colonize regions today known Liberia and Panama. In an attempt to push this plan forward, in 1862, Lincoln invited a delegation of five free Black men, four of which were members of Prince Hall Lodges, to meet with him at the Capitol and discuss the colonization of Panama.

Describing the meeting, Holzer explained that Lincoln “basically said, I want you to know that, in my view, you people are the cause of the war. And that if it wasn’t for your presence here in this country, there would be no war.”

The five-man delegation rejected the idea, and Lincoln abandoned his plan. “They wrote a formal letter back,” Holzer said, “pointing out gently, but pointedly, not to be redundant, that their ancestors have lived in the Washington area for a long time and they weren’t going anywhere.”

Alonsa Tehuti Evans, author and past Grand Historian and Archivist of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the District of Columbia, saw the delegation’s rejection as even more crucial to the perseverance of African Americans in the United States.

“Saying no to the President, they wouldn’t support the plan, I assert is one of the reasons there is a Black Washington D.C. community today,” said Evans at a speech given at the Library of Congress in 2017.

“Because if Lincoln had gotten his way, there would be no African Americans in the country today,” Evans continued. “They all would have been shipped out.”

Prince Hall Freemasons Join The Struggle For Civil Rights

Eventually, Prince Hall Lodges began to gain official recognition from Grand Lodges in the States, and their efforts to support their communities continued. In the 20th century, like the lodges that operated as part of the Underground Railroad a century earlier, Prince Hall Lodges functioned as protected spaces for members of their communities.

“During the segregation era, Prince Hall Lodges were one of the few places that African Americans could congregate,” said Alton Roundtree, Prince Hall Freemason and author of multiple historical books on Prince Hall Freemasonry, describing the limited number of institutions where African Americans could organize.

Wardally called the lodges “a safe space."

"It was a social center, it was a charitable center, it was a mutual-benefit society," he said. "And it became our outlet. But ours.”

During this time, men now heralded as important figures in the struggle for Civil Rights were active in Prince Hall Lodges in states on both sides of the Mason Dixon line. Leaders like late Senator Elijah Cummings, former NAACP President Kweisi Mfume, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and late Congressman John Lewis were all active members.

Like their eponymous founder, Prince Hall masons advocated for the education rights of Black youth. After the NAACP went to court to fight segregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1952, Prince Hall Lodges contributed $20,000 to support their effort.

“Here they are, giving Thurgood Marshall checks,” Waradally said, pointing to a photograph in his collection. “This was the Grand Master in Louisiana, the Grand Master in Georgia, giving him checks for the Research and Defense Fund which helped fund Brown v. the Board of Education.”

And when Prince Hall masons in Jackson, Mississippi constructed the M.W. Stringer Lodge in 1995, they intended the building to be shared. Freemasons were given a safe space to meet and conduct business, while Civil Rights leaders were given a place to organize, including Civil Rights activist and NAACP president Medger Evers.

“It became the permanent home for the Mississippi state conference of NAACP,” said Frank Figgers, Prince Hall Freemason and Vice Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement in an interview with WGNO-TV.

After Evers was assassinated by a white supremacist in 1963, the lodge also held funeral services for him, drawing over 4,000 to mourn the slain Freemason and Civil Rights activist.

“It’s probably one of the most historically significant buildings in the state of Mississippi,” Figgers said.

In the north, Prince Hall Masons were among the men who helped organize the March on Washington in 1963. A. Philip Randolph, a member of the same Lodge in Harlem where Wardally and his brethren meet today, coordinated with his Grand Master to provide transportation to Washington.

“A. Philip Randolph had him charter a train to take Prince Hall Masons, and any African Americans, anybody want to go down to the march,” Wardally said.

Despite their achievements, over 200 years passed before Prince Hall Freemasons began to gain official recognition in the United States.

“By the time you got to the 1980s,” Hodapp said, “It started to become this embarrassment. The Grand Lodge of Connecticut finally stepped up to the plate and said this is insanity. We've got to stop this."

In 1989, the Grand Lodge of Connecticut became the first mainstream lodge to acknowledge Prince Hall freemasonry as a legitimate organization. Even then, acceptance has been a slow process.

Six states, all in the American South, still consider Prince Hall Freemasonry a clandestine organization. Unlike in other countries, there is no overarching, nationally governing Grand Lodge in the U.S. that establishes charters; instead, each state has its own Grand Lodge to which local chapters must petition for acceptance. But in states like Mississippi and Arkansas, these Grand Lodges have continually failed to approve requests from Prince Hall members, meaning Prince Hall Freemasonry remains illegitimate in those places.

“One of these days, they’ll finally recognize we’re all the same color on the inside,” said Bob Simonson Jr., a member of a mainstream Lodge in Grand Rapids, criticizing his fellow masons who have yet to fully accept Prince Hall Lodges. “They’re getting there, kicking and screaming."

In 2017, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge made their latest attempt at gaining recognition, only to have the Grand Lodge of Georgia F&AM again table the action at their annual meeting.

“All of them down below the Mason Dixon line,” Wardally said of the remaining states without recognition. “All of them traditionally slave states.”

Despite their history, mentions of their membership in Prince Hall Lodges also remain largely absent from the biographies of many individual African American icons. Wardally isn’t sure why this is so, but said he thinks it has something to do with the caution of Prince Hall’s members throughout the Civil Rights era. “As a Black man you didn’t flaunt it, because of your circumstance,” Wardally said, explaining the comparative discretion of older generations of Prince Hall Masons.

“I think we hid for too long,” he added. “But we hid for protection.”

Continuing The Legacy

Today, the pressure for African Americans Freemasons to hide their affiliation has abated. There are now Prince Hall Lodges in every state in the US, and the organization operates internationally, with military Lodges in countries like Italy, Korea, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan. Although Prince Hall Lodges do not keep record of the racial backgrounds of their members, Roundtree said he estimated that currently “over 98% is Black and that white and Latino are less than 2%.”

When Congressman John Lewis passed away in July, members of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge F&AM in Georgia, where Lewis had been a Mason for over two decades, honored the civil rights icon with a Masonic funeral service and last rites at a ceremony also attended by mainstream Freemasons.

“The Prince Hall Grandmaster contacted the white Grandmaster privately and said would you and your top officers be interested in participating in this?” Hodapp said. “I don't think there had ever been a public ceremony where the two sides met together as Masons and cooperated as Masons.”

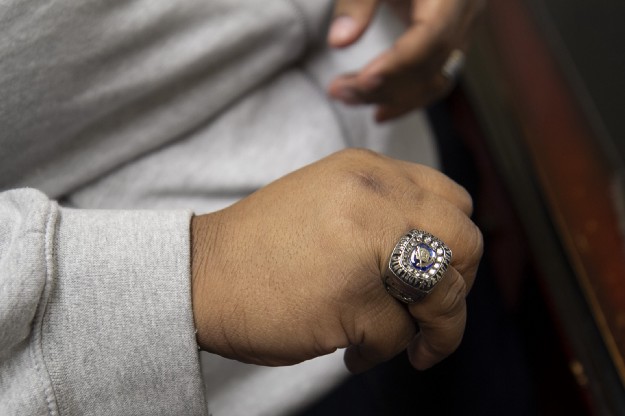

In public and at masonic events, members today proudly declare their allegiance with a sartorial flourish instead of a nod. Discreet indicators like lapel pins have been replaced with bedazzled hats and jackets embroidered with masonic symbols. All of this was on display during the 50th anniversary of the African American Day Parade last year, when members of Prince Hall lodges, alongside their female counterparts, the Sisters of the Eastern Star, were front and center in the procession.

“We wanted to honor them,” said Yusef Hasan, chairman of the annual parade. “To recognize the contributions that they have made to the African American community.”

For Wardally, devoting his life to masonry was the best decision he ever made. A former Worshipful Master, he now serves as the de facto historian at the Prince Hall Grand Lodge in Harlem, where the chapter offers community support and hosts local events. Outside the lodge during their Thanksgiving dinner last year, Wardally greeted friends, shaking hands and embracing.

“I would not have known them, we would have never been as close, we would not even know each other that was not for Masonry,” Wardally said of his fellow masons.

Still, when Wardally finally became a Prince Hall Mason a decade ago, his induction was bittersweet. By the time he joined the organization his family had urged him to join for years, both of his grandparents who had been involved in Freemasonry had passed away. ”My grandmother, until her dying bed, wanted me to join,” said Wardally, calling his hesitation a “regret."

It was a mistake he hopes his own son will not repeat.

“He’s 12. He’s still got a way to go,” Wardally said. “I’m hopeful that when the time comes, he finds it worthwhile to join.”