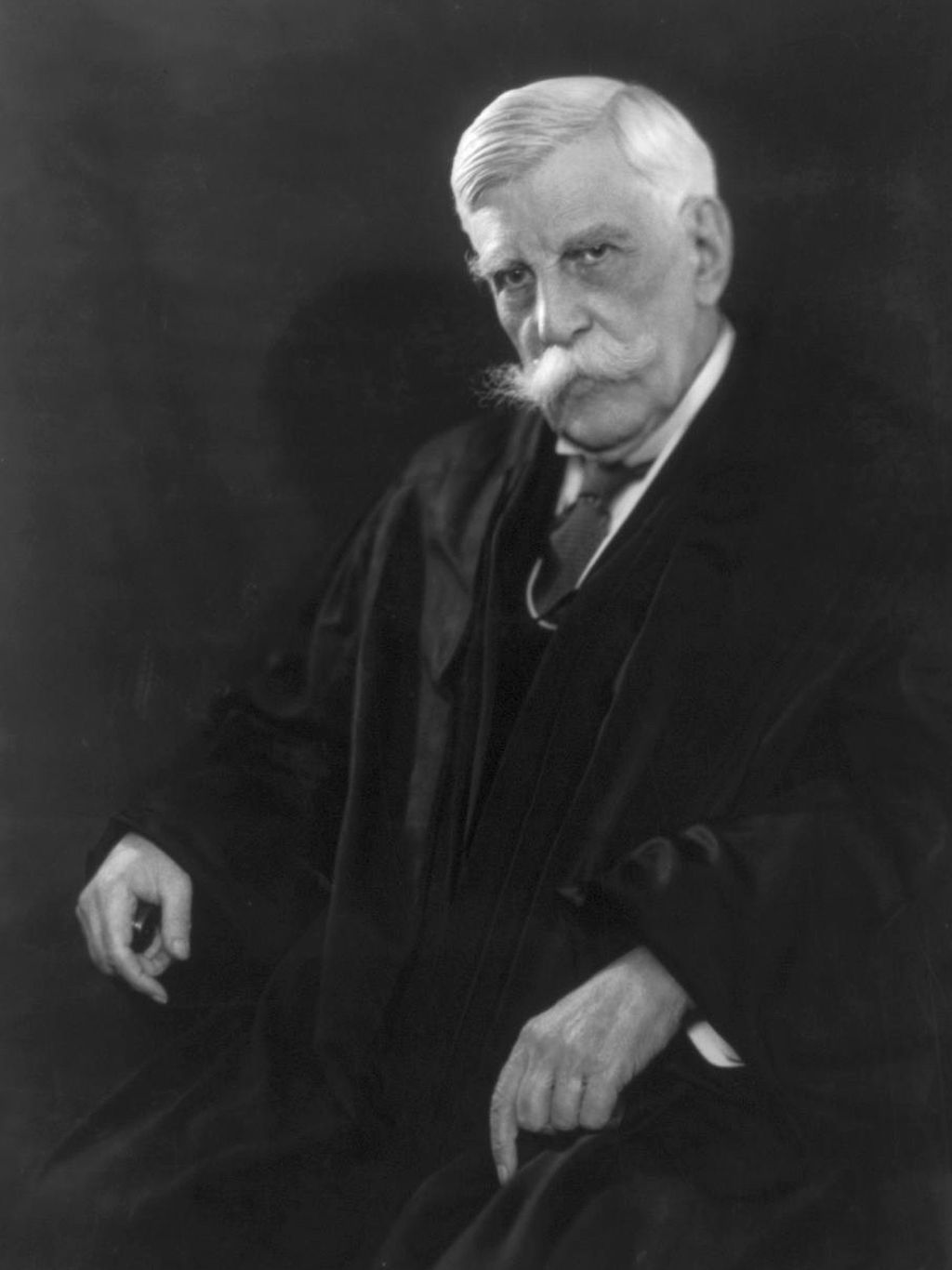

His experiences in the Civil War shaped the mind of one of our greatest jurists.

-

Spring 2019

Volume64Issue2

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was one of the most influential judges ever to take the bench, serving as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court for thirty years and largely defining First Amendment rights as we now understand them. Profoundly influenced by his experiences during the Civil War, Holmes advocated for “legal realism,” observing that “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.” Among his many often-cited writings, Holmes wrote the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion that the government could legally restrict free speech if there existed a “clear and present danger.” Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90, making him the oldest justice in Supreme Court history.

Constitutional scholar Ronald Collins has taught at the University of Washington, Stanford, Temple, and George Washington University. He is the editor of The Fundamental Holmes: A Free Speech Chronicle and Reader.

--The Editors

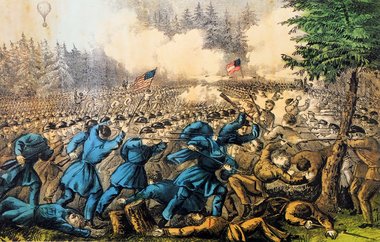

Colonel Edward Baker’s words rang out: “Boys, you want to fight, don’t you?” That question was soon enough answered in blood as Lieutenant Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and his fellow Federal soldiers charged up the steep and perilous paths of Ball’s Bluff. Showers of cannon and rifle fire hailed down. The spectacle of slaughter became real as rebel regiments surrounded them on three sides.

Man after Union man, horse after horse, were cut down leaving pools of blood mixed in mud. Suddenly, Holmes felt the force of battle as a spent musket ball whistled his way and knocked the wind out of him. He fell, but determined to fight on the tall nineteen-year-old Harvard man rose up and moved forward. As Southern sharpshooters targeted down on their sights, he waved his saber high in the air and rallied others to follow. They charged, fell back, reloaded, and then charged up the lethal hill again. This time he was not so lucky: a minié ball bore into his body near his breast.

Had the ball with its conical head hit his liver, his spleen, or an artery? Semi-conscious and spitting up blood, he was dragged to the rear of the regiment. It was all a blur now, all deafening noise now, and all so dangerous now. Time was of the essence. Unless the hemorrhaging was stopped, his blood pressure would drop, sending him into death-demanding shock.

Could his rescuers make it back down the slope? Across the precarious waters of the Potomac? In a clumsy pontoon boat? . . . to a makeshift hospital across the Potomac on Harrison’s Island?

Though he had prepared to die, it was not in his DNA – he was a fighter, someone who summoned death and then resolved to live. He made it across. If luck smiled, he might yet make it. But would it be of any moment? Would he die comatose on a medical cot? With doctors and nurses scurrying around the infirmary tent, one word became manifest in his mind: SURVIVAL.

Stirred by the will to live, he defeated death. In the months and years ahead, he would fight on in battle after bloody battle. His memories of the Civil War left an indelible mark on him that colored all of his many glorious years.

See also "The Long Life and Broad Mind of Mr. Justice Holmes," American Heritage, June/July 1978, by Louis Auchincloss

This brave soldier served in the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Army most of the war and afterwards fused his Darwinian creed into his legal theory as a Supreme Court Justice from 1902 to 1932. What began as heroic but scarring acts on the battlefield transformed itself into a momentous idea in our constitutional history. That idea, both liberating and alarming, was created in the cauldron of war and pointed away from an old America and toward a new one. It is an idea that became central to our modern notion of freedom, especially freedom of speech.

Born into the world of the “Boston Brahmins” (his father coined the phrase) in 1841, young Wendell was exposed to great men and great ideas as the son of physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. and Amelia Jackson Holmes, a self-effacing abolitionist. Dr. Holmes was one of the founders of Atlantic Monthly and published such works as The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table (1858). Young Holmes studied in a private school, then entered Harvard College in the autumn of 1857.

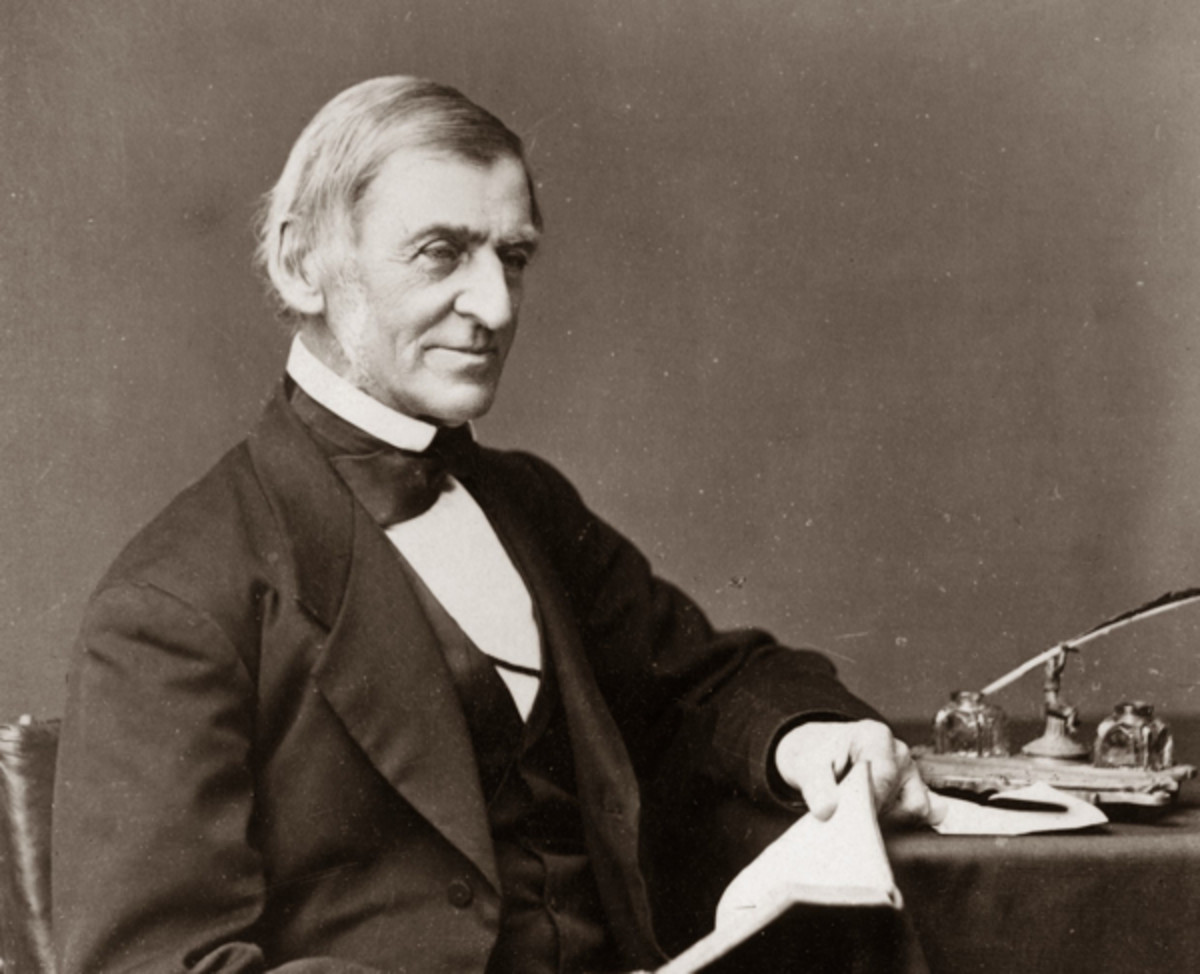

One of the bright lights at Harvard was Ralph Waldo Emerson, the famed essayist, philosopher, and poet. During Holmes’s first year at college, his parents gave him a set of Emerson’s works and in them he found a rebellious sentiment much to his liking. “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist,” Emerson wrote in his essay “Self-Reliance.” The young Holmes wrote an essay for The Harvard Magazine in 1858 that echoed Emerson’s writing, and a few years later penned another essay on Plato and his teacher Socrates. The ever-skeptical, pipe-smoking young Holmes was drawn to the thinking of Socrates, whose “peculiar power lay … in a natural spirit of argumentative questioning” and “keen and caustic spirit of enquiry.” Later serving as editor of the Harvard Magazine, Wendell published essays on subjects from women in college to abolition to the importance of “free will in matters of religion.” These kinds of statements tested the patience of the faculty and college president, who finally contacted Dr. Holmes in an attempt to reign in the free-thinking young editor.

Despite the cerebral joys experienced at the feet of a few men like Emerson, Holmes found relatively little at Harvard to stimulate his inquisitive mind. At a time when the whole world seemed up for grabs, the college and its faculty were too staid in tradition, dogma, and Christian truth. When Charles Darwin published The Origin of the Species in 1859, it was seen more as heresy than science in many quarters at Harvard. Holmes’s philosophy professor dismissed it outright; his chemistry professor lamented its likely impact on undergraduate morals; and the eminent paleontologist and glaciologist Louis Agassiz “publicly disavowed Darwin’s disturbing conclusions.” Only Holmes’s botany professor, Asa Gray, sided with Darwin. For someone invigorated by the intellectual freedom endorsed by Emerson and Socratic skepticism, the new day in science was an exciting time – but it was not in sync with Harvard’s culture. And Holmes knew it.

After three years of uneven attention to his studies. Wendell found a subject in his senior year that inspired him. Both in public conversation and in his writings, he became more outspoken about slavery. He participated in anti-slavery discussions and joined in anti-slavery rallies. Holmes’s abolitionist enthusiasm and that of his colleagues was not, however, then the norm at Harvard. For one thing, Louis Agassiz’s public statements about the inferiority of blacks were being used, particularly in the South, as a defense of pro-slavery positions. Though elder Holmes was not a defender of slavery, he both knew and befriended Agassiz and welcomed compromise with the South. Dr. Holmes felt no particular outrage at southern states that practiced slavery, but Amelia Holmes did, and abolitionism became an important cause for Wendell Holmes and his mother.

In July 1861, Holmes and his classmates received their diplomas from Harvard. In an autobiographical sketch, he wrote: “At present I am trying for a commission in one of the Massachusetts regiments . . . and hope to go south before very long. If I survive the war I expect to study law as my profession or at least for a starting point.” Shortly afterwards, the skinny, long-bodied, and bookish young man enlisted for a three-year commission in the Twentieth Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. “In my day,” Holmes recalled 65 years later, “I was a pretty convinced abolitionist.” While his father wrote poems of peace and sought compromise, a far more resolute Wendell went off to war to fight the good fight. His life would never be the same afterwards.

The numerical toll of the Civil War is hard for a modern mind to comprehend. The number of soldiers who died, an estimated 620,000, is nearly equal to the American fatalities in all its other conflicts combined. Relative to the size of the population, the rate of death of nearly 2 percent would mean six million fatalities in the U.S. today. Beyond the staggering body count, there was the horrifying spectacle of death as Holmes and his fellow soldiers experienced first-hand. They saw bullets and shrapnel tear into their friends’ flesh, limbs stacked next to surgeons’ tables, and corpses dumped into trenches. “As you go through the woods you stumble constantly,” he wrote one day to his parents, “and, if after dark, as last night on picket, perhaps tread on the swollen bodies already fly blown and decaying, of men shot in the head, back or bowels – many of the wounds are terrible to look at.”

Holmes experienced a philosophical crisis: what grand principle could begin to justify such carnage? What conceivable purpose could explain the staggering costs of war?

The soldier’s experience would shape the judge’s jurisprudence. Max Lerner, in his book The Mind and Faith of Justice Holmes, points out that “the experience of the Civil War was the maturing force in Holmes’s life.” He learned that there is great risk in life and the best comes out under fire, much in life depends on risk and that the law must recognize that quality.

These elements played out time and again in Holmes’s writings – letters, articles, books, and judicial opinions – in ways at once rhetorically powerful and analytically forceful. The idea of struggle, rooted in the blood-soaked fields of battlegrounds seeded by human casualties, became central to his thought, including his thoughts on freedom of expression. At first, the struggle was seen through a romantic lens – the rush of going off to war with friends to fight for a noble cause and to do one’s duty proudly. “Our hearts were touched by fire,” Holmes later recalled. And then he altered the metaphor, but to the same effect: “[W]e have seen with our own eyes . . . the snowy heights of honor . . . .” It was akin to a holy crusade, in defense of “the cause of the whole civilized world.”

That was their creed, and theirs was a noble war fought by honorable and brave men wed to the highest of principles. It was that faith that made hellish fighting possible. “If one didn’t believe that this was such a crusade,” Holmes wrote, “it would be hard to keep the hand to the sword . . . .”

And so Wendell, age 20, went into battle. It began in earnest in October 1861 at Ball’s Bluff where a Confederate ambush took a heavy toll of the 1,700 Union soldiers who faced a barrage of musketry and cannon fire in front of them and a deadly body of bullet-hailed water (the Potomac River) behind them, which made retreating near impossible. Holmes was one of those wounded – shot in the chest near his heart and lungs, this after but an hour of battle. “I felt as if a horse had kicked me,” he wrote in his pocket book diary. This time death passed him by – one of his fellow soldiers squeezed the bullet ball from his chest and gave it to him as a battle souvenir. With that spent bullet in his pocket, he returned to home to Boston (to 21 Charles Street) to convalesce.

By March 1862, the young man was back in action, now as a captain. He was in Washington for a short while, awaiting his orders. When those orders came, Holmes and his regiment boarded steamers to Hampton Roads, Virginia. There they would join General George McClellan’s army. In the months ahead, Holmes fought in a number of engagements including at Fair Oaks, where he led his troops into battle with sword and pistol flying. Once again, there were heavy casualties on both sides, though Holmes survived to fight another day. Shortly afterwards, there was an effort to take Richmond, the Confederacy’s capital.

The campaign produced more miserable face-to-face fighting and the specter of soldiers armed with sabers, bayonets, muskets and cannons, all charging at one another. There was the damp and cold land caked with mud, polluted water, and then there was that “spasmodic pain” caused by dysentery. If a bullet or shell didn’t claim a man’s life, sickness was always there to demand its fatal share. The “immense anxiety,” the unimaginable “hardships,” and the “hard fighting” weighed heavily on the young soldier in letters he wrote to his mother. The romance of war faded, particularly when victory eluded them. Try as they did, the Union forces could not yet conquer Richmond.

In August, the Peninsula Campaign headed north to defend Washington against Confederate attacks planned by General Stonewall Jackson, or so it was feared. When that threat failed to materialize, Union forces regrouped. About that time, when he was out on a short leave, Holmes stayed at the National Hotel in Washington, this as the Army of the Potomac prepared for new engagements. On September 7, 1862, Union troops left Washington en masse under the leadership of General McClellan.

As the troops moved northward they were greeted with excited jubilation in some Maryland towns – it invigorated them at a time when defeat seemed entirely possible. Victory was on the Union side as corps commanders like “Fighting Joe” Hooker prevailed, leaving behind a cornfield spotted with dead bodies. “Hooker licked the Rebs nicely,” Holmes wrote home. Hell, however, awaited them. It came in a conflict near Sharpsburg, Maryland. This clash, known as the Battle of Antietam Creek, was fought on September 17, 1862.

At first, the assault on the Confederate position seemed successful as rebel troops began to fall back, but then – as if out of nowhere – Union forces were attacked from their rear. They had walked into an ambush. “Four hours of action . . . left a carpet of blue-clad corpses strewn across the fields” along with a “carpet of butternut and gray-clad corpses in the appropriately named Blood Lane.” The hand of tragedy was a heavy one – the combined casualties for the blue and gray, not counting the missing, for the “twelve hours of combat came to 22,719.” In this maelstrom of agony, Holmes was wounded, this time in the back of his neck: “Unusual luck,” he wrote to his parents the following day, “ball entered at the rear, passing straight through the central seam of [my] coat and waistcoat collar coming out [towards] the front on the left hand side – yet it don’t seem to have smashed my spine or I suppose I should be dead or paralysed or something . . . .”

Holmes was left for dead, though he was found that evening wandering aimlessly having faded in and out of consciousness. His life had been spared – again. Miraculously, he survived another close call when shortly afterwards he was taken to a farmhouse to recuperate temporarily, this as rebels shelled the place.

Meanwhile, word of his injury was telegraphed to his parents. “[M]y household was startled from its slumbers by the loud summons of a telegraphic messenger,” Dr. Holmes recalled. “Capt. Holmes wounded shot through the neck thought not mortal,” was the message. Hurriedly, the elder Holmes left Boston in search of his wounded son. Looking for the place where his had been transported, he went to Philadelphia, Baltimore, Frederick, Antietam, Middletown, Keedysville, Harrisburg, and then and then to Hagerstown where on September 25th he boarded a railroad car filled with wounded soldiers. Then it happened: “In the first car, on the fourth seat to the right, I saw my Captain; there I saw him, . . . my first-born . . . . ‘How are you boy?’ / ‘How are you dad?’”

Holmes returned to Boston, to recover, and after some convalescence time, it was back to duty, this time in the Fredericksburg area of Virginia. Here, too, the fighting was fierce, both close up and as far as a brass telescope could carry an eye’s sight. “For the Twentieth Massachusetts the ninety days after Antietam were among the most tumultuous of its existence.” When December arrived, it brought not only a bitter cold but also bitter setbacks as Holmes’s regiment failed to drive beyond Fredericksburg and towards Chancellorsville. What had begun as a hopeful victory with the Federal bombardment of Fredericksburg – later judged by some to be an act of wanton destruction – ended in crushing defeat, massive slaughter, and pervasive losses so ghastly that the living began to question the purposes of both God and country. Too ill to fight (he was sick with dysentery), he could only wait in “helplessness and hopelessness” as his fellow soldiers died as Union troops suffered a “great bloodletting.” It was during these “anxious and forlornest weeks” that soldier Holmes began to get “indifferent . . . to the sight of death – perhaps because one gets aristocratic and don’t value much a common life . . . .”

Though death was everywhere and beckoning everyone, the resolve of soldiers on both sides had not diminished. Into the eternal breach they went, thousands and thousands of them. “I see no further progress,” thought Holmes as Christmas of 1862 neared. “I don’t think either of you,” he told his parents in a letter, “realize the unity or determination of the South. I think you are hopeful because (excuse me) you are ignorant.” And so the terrifying war played out, with the only hope being that civilization and progress might “conquer in the long run,” he wrote his father, “and will stand a better chance in the proper province . . . .” It smacked of Darwinism. By that evolutionary measure, life could be cruel as when men fought with savage fervor hand-to-hand and used the butts of their muskets to kill one another.

The seeming futility of it all began to war with Holmes’s survival instincts, which became even stronger after he was wounded on May 3, 1863 in a battle near Chancellorsville. Shrapnel from an artillery shell lodged in his foot. Though there was some fear he might lose a limb, he was fortunate. Once more, he returned home to the family’s brick house to recuperate; this time he took several months off. Back home, where he hobbled on crutches, life came back to normal and then some. “He lied on the couch,” his doctor reported, “and receives lots of pretty company.” He even appeared “jolly.”

Holmes grew weary of close-up conflict. Thus, when he returned to service he did so as an aid to a general, Horatio G. Wright of the Sixth Corps. This may have seemed like a safe position, but it didn’t play out that way. The carnage didn’t stop. The various conflicts in Northern Virginia were ghastly in unimagined ways. At one point, for example, while Holmes fiddled with his horse’s bridle, a cannon ball took off the head of one of his fellow soldiers; the infantryman’s blood and brains splattered everywhere.

On May 5, 1864, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Army of Northern Virginia in an area covered with thickets. This was the battle of the Wilderness, a two- day conflict that was one of the bloodiest and most puzzling of the Civil War. It was during this gruesome conflict that Henry L. Abbott – a Harvard man, a Copperhead, and one of Holmes’s closest friends – was shot. “Abbott wounded severely don’t know where,” Holmes wrote back to his parents on May 6th. A bullet ball had torn into his abdomen. According to an eyewitness account from the time, he “lay on a stretcher, quietly breathing his last – his eyes were fixed and the ashen color of death was on his face.” Ironically, and saddened as he surely was, the quality that Holmes so admired in this platoon leader was the “splendid carelessness of death” with which Abbott forged headstrong into battle.

The horror of this battle fought in fog and rain – the so-called Bloody Angle of Spotsylvania – burrowed into Holmes’s being. The morning following the battle, Holmes wrote in his diary: “Day spent in straightening out Corps, burying dead . . . In the corner of the woods . . . the dead of both sides lay piled in trenches 5 or 6 deep – wounded often writhing under superincumbent dead – The trees were in slivers from the constant peppering of bullets.” On May 16, 1864, a worn and depressed Holmes wrote home: “Before you get this you will know how immense the butcher’s bill has been . . . . [T]hese nearly two weeks have contained all of the fatigue & horror war can furnish,” he wrote his parents. “Nearly every Regimental officer I knew or cared for is dead or wounded.” By late June, the pressure had not let up: “These last few days have been very bad . . . I tell you many a man has gone crazy since this campaign began from the terrible pressure on mind and body . . . .” Between May and June the fighting around places like Spotsylvania and Chancellorsville was so fierce that it claimed the lives of 50,000 men (Yanks and Rebs) in a single week of brutal battle. The fighting – day and night – was hellish; the devastation horrendous.

Captain Holmes had seen enough bloodshed. The life of combat that first energized him, then desensitized him, now had changed him. “I am not the same man,” he admitted. “[I] may not have the same ideas . . . & certainly am not so elastic as I was . . . .” On July 8, 1864 he told his mother to “prepare for a stratler” – he was ready to leave the service.

When Holmes’s military service ended, on July 17, 1864, he no longer romanticized the brutish ways of war. While he remained wed to the idea of duty, he was far more guarded in his idealism; one might even say he became somewhat cynical. Here is how he put it in an earlier letter penned on a cigar box, one that his father had sent him: “I started in this thing as a boy,” he noted, but now “I am a man and I have been coming to the conclusion for the last six months that my duty has changed – I can do a disagreeable thing or face a great danger coolly enough when I know it is a duty – but a doubt demoralizes me as it does any nervous man – and now I honestly think the duty of fighting has ceased for me – ceased because I have laboriously and with much suffering of mind and body earned the right . . . to decide for myself how I can best do my duty to the country and, if you choose, to God . . . .”

The war was behind him now. But the memories – born on the battlefields – served as reminders of a passion and agony so intense that life seemed meaningless without those “high and dangerous” moments. In the end, the “war in retrospect became . . . an overreaching, ‘official’ memory that helped Holmes avoid recalling some more specific and more candid memories.” However understood, he would, for a time, share those memories with others, in prose that would deservedly claim a place alongside any of the great American speeches. And then, he would stop speaking and reading about the war.

Thirty some years after Holmes hung up his military uniforms, his view of the Civil War was nowhere near as glum as when he left. “War, when you are at it, is horrible and dull, he said around 1895. “It is only when time has passed that you see that its message was divine.” Two years later he admitted: “My memory of those stirring days has faded to a blurred dream.”

Even so, Holmes delivered his “divine” message, if it can be called that, in several remarkable speeches he gave between 1884 and 1903. Veterans groups and others could not help but be moved by his eloquent remarks delivered with his signature baritone voice. War had taught the young line officer the importance of duty, that obligation born out of both pragmatic concerns and a kind of romanticized Darwinism. That idea of duty was likewise linked to honor and chivalry and all were mixed in a cauldron of a destiny at once determined and yet unknown.

In the public eye, the honors the young Holmes won in the Civil War made him a person in his own right. He was now more than just the “son of Dr. Holmes.” He was more than a shadow. That honor, buttressed by an ambition to establish himself professionally, would permit him to define himself to the point that one day he would no longer use the designation “Jr.” to identify himself. In other words, his character, both personally and professionally, were linked to what he had done and accomplished between 1861-1864. As the note materials following the various entries also indicate, the Civil War also influenced Holmes’s overall philosophy as well as on his First Amendment jurisprudence. The more one is steeped in the Civil War experience as Holmes both lived and portrayed it, the more one realizes just how indispensable it was to the views he would express later in life. He best summed up the gist of it in three words – “life is war.”

“The law does not mean sympathetic advice [that] you may neglect if you choose, but stern monition that the club and bayonet are at hand ready to drive you to prison or the rope if you go beyond the established lines,” he observed at a banquet honoring Admiral Dewey. “The possibility of having to face death in battle, which throughout all history has been the background of men’s outlook upon life, has given shape and color to what at this day we most value in men.”

“When I hear people talk about civil life as needing and teaching a courage equal to that of war, I feel very sure that I am listening to a noncombatant who never has known what it is to expect a bullet in his bowels in thirty seconds or to sail an iron clad over a mine.

“People dwell on the sorrows of war. I know what they are. I saw my share of them when I was young with the Army of the Potomac. I shudder at them. I abhor the Jingo spirit. I would do all that might be done honorably to avoid them. But the horrors of war after all are bodily suffering, the loss of property, and the loss of life. There are spiritual losses that are a thousand times worse. It is worse to be a coward than to lose an arm. It is better to be killed than to have a flabby soul. The true teaching of life is a tender hard heartedness which has passed beyond sympathy and which expects every man to abide his lot as he is able to shape it. . . .

At a time when patriotism and religious sentiment provided most Civil War soldiers with some sense of comfort from the senseless agony of annihilation, the Holmes of this period, circa 1903, saw life through a different prism. His sense of duty was tied to an unknown destiny, which causes one to embrace life and “function” to his or her fullest and then to leave a “broad passage for the beetle that is to be.” That is “the faith” to which Holmes subscribed. He was very much interested in what he labeled “our influence on those who come after us . . . .” By that measure, life was like the common law, forever evolving as it built more and more on the past.

The Civil War experience produced in Holmes a mindset that took hold of his outlook on life and law. First, there was the role of conflict in the affairs of men: Life, like war, consists of conflict, which can strengthen us; that could well have been his motto. Next, there is the role of uncertainty in all things human: There is no certainty in life, only the ongoing pursuit of knowledge, which was his creed.

Coupled with that there was the notion of evolving truths: We must be prepared to relinquish our “truths” to make way for new ones is how he might have put it. And then there was the role of hope: The hope – and it is no more than a hope – is that evolution will produce a better species (“better” in an evolutionary sense); that might well have been his counsel.

Truth, whatever it is, may or may not be transcendent – Holmes played this card close to his conceptual vest. And finally, there was freedom, that peculiar word in Holmes’ philosophical lexicon: Freedom belongs to the victors, the majority’s collective will governs – this was Holmes flying the Darwinian flag.

It was that struggle, that unending war within us and within our culture, which the old soldier engaged, struggled with, and even prepared to die for if need be. That, at any rate, was the “fighting faith” of the “Captain and Brevet Colonel” buried at Arlington National Cemetery (section 5, lot 7004).

Ronald Collins was the Harold S. Shefelman Scholar at the University of Washington School of Law. Portions of this article were adapted from his book, The Fundamental Holmes: A Free Speech Chronicle and Reader (Cambridge University Press, 2010). His new book, Reason in Ruins: America’s Destiny in Perilous Times, is due out in Oct. 2019.