In a pivotal trip in 1967, Sen. Kennedy saw first-hand the effects of poverty in the Delta.

-

Spring 2019

Volume64Issue2

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a son of America’s promise, power, and privilege, knelt in a crumbling shack in 1967 Mississippi, trying to coax a response from a child listless from hunger. After several minutes with little response, the senator, profoundly moved, walked out the back door to speak with reporters. He told them that America had to do better. What he was seeing, as he privately told an aide and a reporter, was worse than anything he had seen before in this country.

As he toured the Mississippi Delta, an impoverished cotton-producing region in the northwest corner of the state, that warm April day in 1967, Kennedy talked with mothers about how they fed their children. He looked in empty refrigerators and asked school children about their breakfast. The depths of deprivation he found in Mississippi stunned both Kennedy and, because of the press coverage that inevitably followed him, the nation.

Kennedy visited Mississippi in 1967, along with Senator Joseph Clark of Pennsylvania, as part of a Senate subcommittee’s examination of War on Poverty programs. His journey provides a useful lens to examine the impact of waves of change roiling the state and the nation at the time, as well as offers a deeper understanding of Kennedy’s growth as a leader.

His visit was a catalyst that drew out the extremes of Mississippi’s culture at the time. In Jackson, members of the Ku Klux Klan met him at the airport, carrying signs castigating him for his position on Vietnam and distributing flyers predicting his death. They were only echoing the hatred of Kennedy that many white Mississippians harbored because of his role as attorney general in the integration of the University of Mississippi, and other conflicts over civil rights in the state.

However, both black and white civil rights advocates on the frontline in Mississippi were unimpressed with his record. Many of them had struggled through life-threatening violence with little or no help from the Kennedy administration’s Department of Justice. They viewed Kennedy as a ruthless political dealmaker who put too much priority on placating powerful southern politicians in Congress. To advocates like Marian Wright, a 27-year-old NAACP attorney who was one of only five black lawyers in the state, his visit had the potential to be just another chance to be disappointed.

In contrast, Kennedy and his brother were heroes to many of the ordinary African American residents of the state. In fact, just about forty-eight hours after Kennedy landed in the state to the belligerent shouts of the Ku Klux Klan, hundreds of African Americans in Clarksdale cheered him and, as one journalist who was traveling with him recalled, “reached up to him like they were trying to touch the robes of Jesus Christ” at his last stop in Mississippi.

On April 11, 1967, Kennedy, his aides, journalists, and civil rights advocates flew from Jackson, Mississippi to Greenville, where they toured job training classrooms and a cooperative farm for displaced farmworkers. After lunch, the group drove north through the Mississippi Delta.

With a federal marshal at the wheel, Kennedy, Wright, and his aide, Peter Edelman settled in for a thirty-eight-mile drive to Cleveland. They had been riding together since the airport in Greenville, and Wright found Kennedy, who rode in the front, to be a surprisingly pleasant companion.

“He was sort of relaxed; he was funny; he was honest,” she would later recall.

Always curious, Kennedy quizzed Wright about her life in Mississippi and what motivated her to work in such a troubled place. He asked what she was reading, and they discussed her selection, The Confessions of Nat Turner, and moved on to how to encourage children to read. She was firm with her boundaries, though. When he turned his questions to her personal life (When was the last time she went to the movies? When had she last gone on a date?) She quickly told him that it was none of his business.

Kennedy then shifted his attention to the attitudes of Mississippi people, black and white, toward the federal government. He quizzed Wright about the shift in rhetoric toward black power, which activists such as Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had first embraced publicly just a year earlier not too many miles from where she and Kennedy were traveling in Mississippi.

Though reasonable enough, these questions touched a nerve in the young NAACP lawyer. Wright was not naïve. She knew full well the political considerations Kennedy had wrestled with as attorney general: the need to placate powerful southerners in Congress; Cold War intrigue; the concerns about public opinion after a razor-thin victory in the 1960 election; and his role as his brother’s protector, just to name a few. But Wright knew something else, something that was more powerful, more visceral, more painful, than her intellectual understanding of a complex political situation.

Marian Wright knew the reality of Mississippi jails. Secret trials. Beatings. Lynchings. Snarling dogs loosed on children and old people. Medgar Evers, dying in front of his children from a sniper’s shot. James Meredith writhing on the highway. Vernon Dahmer, the flames and smoke from a firebomb searing his final gasps for breath. James Chaney, Mickey Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, holes in their heads, buried under tons of Mississippi mud. To many of the people helping African Americans in Mississippi struggle to exercise their rights as ordinary citizens, the Kennedy Department of Justice had been, in fact, no such thing.

The failures of the Kennedy administration’s approach were clear to her from her first visit to the state over spring break as a young law student from Yale in 1961. The first night she was in Greenwood, someone burned down SNCC’s house. The next night, someone shot at another house where they were staying. The third day, she watched police beat people both young and old who were rallying for voting rights. Officers arrested them and locked her out of the courthouse and tried the protestors without a lawyer. Frantic, frightened, and outraged, she called Justice Department attorney John Doar just before the telephone lines going out of town were cut.

“I said, ‘John, you really don’t know what’s going on here,’ and I described this whole scene. John’s first words—which, in retrospect were right—were infuriating at the time—‘Stop being emotional and talk like a lawyer!’” Wright would later say as she recounted their conversation.

“All I could say was, ‘what the hell are you going to do?’ . . . I never had felt such a feeling of total isolation in my life . . . just total helplessness. I had told John what was going on; he was very calm, you know. ‘We’ll send somebody in to investigate,’ which is the word I got to hate worst of all,” she said.

Wright knew that it was this kind of bitter disappointment that had fueled the anger and shift toward black power within the ranks of SNCC. So many of those workers were, early in the movement in Mississippi, “the most idealistic, the most trusting. They really believed they could change the world,” she would later say. They had hoped in the promise of a Kennedy administration, which, instead, had left them too often at the mercy of their oppressors.

It was spring, and in the fertile fields of the Delta outside her car window, a cycle as old as time was beginning anew. This year, though, thousands of the people who had worked so hard on the land with so little to show for it were not needed and had nowhere to turn. Oh, there was so much to say.

In that moment, however, Wright instinctively drew upon a southern tradition, one that ran deep in both the black and white communities in her native region: she told Robert Kennedy a story.

In 1964, a young girl who had attended a Freedom School wrote a fable, one that Wright had read in a newsletter and never forgotten. As Kennedy listened, the caravan of cars rolled down the long, straight roads of the Delta. Marian Wright, her straightforward, unflinching manner contrasting with her soft, South Carolina vowels, told him about “Cinderlilly.”

Once upon a time, the story went, a little black girl in McComb, Mississippi, watched as the grown white folks went to a beautiful ball at the armory downtown. Wide-eyed as any child at the splendor, Cinderlilly asked her mother if she too could go to the ball. Her mother, knowing the truth about Mississippi but not wanting her dear child to be disappointed, would put her off, saying, “No, Cinderlilly, you’re too young.”

Years passed, but Cinderlilly did not forget her dream. She persisted, but her mother would always find some excuse. Finally, though, the day came when the girl was obviously old enough to go to the ball. Her mother reluctantly agreed. “All right,” she said, “but you really can’t go because you haven’t been invited.” Cinderlilly, however, was undeterred.

“Oh, yes. I’ve got my invitation,” the girl responded, “I’ll take the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, and that’ll get me in the ball.” Her mother wasn’t sure that would work, but Cinderlilly replied, “Oh, I think it will, but if that doesn’t work, I’ve got a new card. I’ve got the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Surely that will get me in the ball.”

The mother thought of another obstacle. “Maybe you’re right, Cinderlilly, but who is going to take you? You can’t go to the ball without an escort.”

Her daughter had answer for that too. “Oh! Prince Charming, Bobby Kennedy, is going come and take me!”

“And the mother said, . . .” Wright went on with the story, as Kennedy listened intently, “‘You’re sure he’s going to show up?’ And the little girl said, ‘I’m sure he’s going to show up,’ So sure enough, Prince Charming promised her he would come and take her to the ball. And the night came. And the little girl’s mother pressed her pretty little clothes, and she was going down to the ball. And she was very excited.”

“At the last minute,” Wright continued, “Prince Charming called and said he couldn’t come. The little girl was crushed. She was terribly scared, but she said, ‘I’m going to go anyway.’ And she took her little Fourteenth Amendment, and she’s packed up her little Civil Rights Act of 1964, and went down to the ball,” Wright told him.

When Cinderlilly arrived, the doors were closed to her, but she could hear the ball going on inside. Summoning her courage, she knocked and knocked and kept knocking.

“Finally the doors opened,” Wright said. “They looked at her . . . The people at the ball stopped and everybody looked at the little girl and said,‘ What are you doing here?’ She said, ‘I’ve come to the ball.’”

“They said, ‘Where’s your invitation?’ So she pulls out the 14th Amendment and she gives it to them. And the doorman started laughing, and said, ‘this won’t get you anywhere,’ and he passes it around the room, and everybody starts laughing.”

Cinderlilly began to cry. But then she remembered the new Civil Rights Act in her pocket, and gave that to them. “And everybody kept laughing and kept laughing,” as Cinderlilly stood at the door, just outside of the ball, her hopes crushed, tears rolling down her face.

As Wright concluded her tale, Kennedy said nothing. Then, after a moment, Wright broke the silence and said, “It’s a cruel story, but I think it’s as much as anything how little children and how people down here view the disappointments in the federal government. You know, Prince Charming simply didn’t show up.”

Kennedy remained quiet.

After his death, Wright said about that moment, “[H]e felt very badly. He really . . . really felt very badly. And there’s not much you can say to something like that.”

Outside the car, the muddy fields of April rolled on by as they sped toward Cleveland. The sun had come out, and the greening landscape was punctuated by the occasional white clapboard church, corrugated tin farm building, or houses—the unsteady, gray unpainted shacks of the farm workers contrasting with the pleasant, well-cared for homes of the planters. Along the way, the ever-present, half-starved dogs of the Delta peered around corners or stood on thin legs nosing through litter tossed near the roadside.

Nine-year-old Charlie Dillard’s life was filled with uncertainties— his grandfather’s unpredictable temper, his mother’s frequent and often frantic search for work—just to name two. However, some things were certain. His grandparents’ three-room home in Cleveland, Mississippi, which he shared with his eight brothers and sisters, as well as various aunts, uncles, and cousins, would be cold in the winter. It would be sweltering in the summer heat. And there would be nights that he would go to bed hungry, even days in a row when he would have almost nothing to eat. There would be times when, with his growing legs aching, his stomach hollow and gnawing, he would lie awake and weep.

At the time of Kennedy’s visit, Charlie lived on Chrisman Avenue in the Low End section of the East Side, a poor, black neighborhood a few blocks from the center of the former railroad town. The rail line that ran through the heart of town had shaped both Cleveland’s history and the racial landscape of the city, acting as a dividing line between mostly all-white upper- and middle- class homes and the East Side, where closely packed, weather-beaten, often crumbling shacks housed much of the city’s African American population.

Charlie’s grandfather, Joseph Dillard, had grown weary of always owing the landowner, and in 1960, he gave up sharecropping and moved his family to Cleveland, where he found work at the county road barn. His daughter, Pearlie Mae, had stayed in the country with her own growing family to work in the fields. Chopping and picking cotton was all Pearlie Mae Dillard knew. Because her parents needed the help of all their children in the fields, she had rarely ever gone to school. Starting late after the cotton-picking season and leaving in the spring for planting and weeding meant she was always behind in her studies. Overwhelmed and struggling, she gave up attending school. Then the babies started coming, first Rob and then Charlie and his twin brother Charles, and then six others, all delivered by midwives in tenant shacks deep in the rural Delta, far from medical care. One of the babies died from pneumonia after only a few months of life, as his mother watched, helpless to save him.

As the 1960s unfolded, waves of change began to sweep over the Delta. The fieldwork grew scarce and unpredictable, and Pearlie Mae, who remained a single mother, struggled to care for her children. Charlie never knew his father, and his mother moved him and his brothers and sisters often, until, a short time before Kennedy visited, they landed at her father’s house in Cleve- land. Pearlie Mae had heard that there was work in Florida in the vegetable fields for more money than she could make in Mississippi, and she headed down there to find out.

The addition of eight hungry children to his household weighed heavily on Joseph Dillard. He already had a few of the youngest of his nine children still with him, and some of them had babies of their own. By April of 1967, there were fifteen people living in the small house, and his county wages were hardly sufficient to feed, clothe, and care for all of them. Angry over Pearlie Mae’s departure, Joseph Dillard was often harsh with her children. His wife, Fanny, however, always insisted that they take their grandchildren in and loved them all in her quiet way. A deeply religious woman, she often gave up her own meals for them. At times Joseph would order her not to feed Charlie and his brothers and sisters if the food got scarce. However, if his grandmother had something, she would share it with the children when her husband left the house.

When the family did eat, it was usually a meager meal of molasses and bread or cornbread and beans, supplemented with vegetables from the garden during the summer. Occasionally they might have salmon croquettes, but they almost never had meat. Sometimes, their neighbors in the close-knit East Side community, poor as they were themselves, sent what- ever leftovers they had to help Fanny Dillard feed the children.

With no money for toys, Charlie and the other children spent most of their time playing together in the grassless yard outside their grandparents’ home. He was playing there that April afternoon when he looked up and saw the newsmen aiming their big black cameras at a man in a suit coming toward his house. Kennedy, escorted by Amzie Moore, local civil rights stalwart, was walking the unpaved streets of the East Side.

To Charlie’s surprise, Kennedy approached the Dillard home, but stopped to talk with the children before going inside. Kennedy greeted Charlie, delighting him by shaking his hand, a shocking thing for a white man to do in 1967 in Mississippi. Kennedy asked Charlie about school, which he was not yet attending, then asked what he had eaten that day.

“Molasses,” Charlie answered simply.

As Kennedy talked with the other children, Charlie ran inside the shack to tell his grandmother about the visitors, and Kennedy followed, climbing the unpainted steps to a screened-in porch. Charlie watched from the corner behind his grandmother.

“How do you feed all of these children?” Kennedy, who was the father of ten children at the time, asked. It was hard, but they got by, Fanny Dillard told him. Opening the door to the screened porch, Kennedy greeted Fannie Dillard quietly, almost shyly. Dillard, a sturdy woman with expressive eyes, had her hair tied up in a ragged scarf and wore a worn housedress. The senator asked her about her family’s meals that day.

“No, didn’t have no meat, sir,” she was quick to answer.?

Then what did they have to eat? Kennedy wanted to know.?

“Bread and syrup,” Fanny Dillard replied.

Kennedy struggled to understand her Mississippi accent.

“Bread and what?” he said.

“S-y-r-u-p! S-y-r-u-p!” she said, her voice rising.

“Syrup . . . and bread,” Kennedy repeated, slowly. “What did . . . Did they have any lunch?” the senator asked.

“No, I ain’t given ’em no lunch,” Charlie’s grandmother said, frowning and glancing down. Then, looking up again to meet Kennedy’s gaze, she added, “I won’t feed ’em again ’til the evening,”

“But they, but they . . .” Kennedy stammered.

“ . . . I can’t hardly feed ’em but twice a day,” she said, raising her voice a little as she talked over his objections.

Silenced, Kennedy blinked, and then his eyes widened momentarily in surprise. He looked over her shoulder to Charlie, who stood leaning on the rail in the corner of the porch, his head resting on his thin arms. Kennedy’s gaze shifted then toward the yard where other children from Cleveland’s East Side milled around the newsmen.

He nodded to Mrs. Dillard and looked down. With a small, rueful sigh, Kennedy turned to go.

Charlie’s grandmother stood still on the porch, her left hand on her hip. She stared into the middle distance, biting her lip as he walked out.

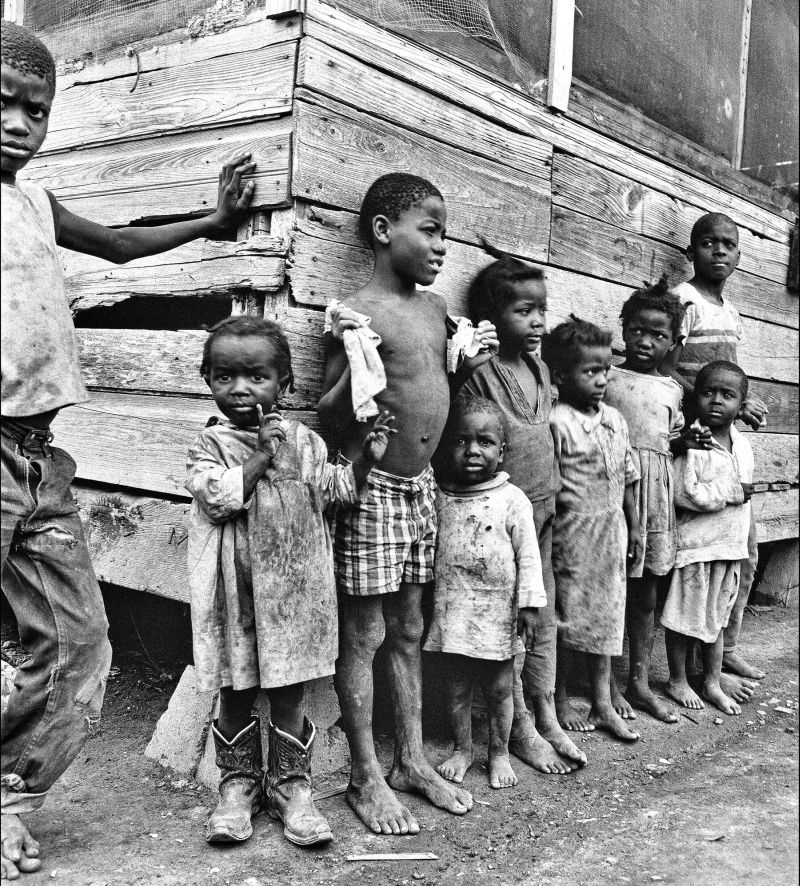

As Kennedy came out of the Dillard home, some of neighborhood children stood outside lined up against the weathered boards of the screened-in porch. Flies buzzed around them. They wore ragged, grubby hand-me-downs that were too small or too big. All but one of them were barefoot, and their feet and legs were grey with dust. One little boy, maybe as old as three, with a running, unwiped nose and a shirt full of holes, ignored Kennedy and stared into the news camera with sad, worried eyes.

Kennedy stopped in front of Rob Dillard, Charlie’s eleven-year-old brother.

“What did you have for lunch?” Kennedy asked.

“Didn’t eat lunch yet,” was Rob’s quiet response. He looked up and smiled shyly at Kennedy, who smiled back at him reassuringly.

“You haven’t had lunch yet, eh?” Kennedy said, even though it was well into the afternoon.

“No,” Rob said, and looked down at his siblings.

Kennedy watched him, his smile fading. Looking suddenly grave, Kennedy bit his lip and turned to go, caressing the boy’s cheek as he passed, and then touching Charlie’s sister Gloria’s cheek gently with the back of his hand as he went by.

As the father of so many children – 10 by this time --, Kennedy was well versed in what made preschool children happy.

As he walked by the line of children, he came to a girl of about three wearing a tattered, dirty dress and dusty, too-large cowboy boots. She was backed up against her brother, watching Kennedy warily.

“Nice boots!” he said, with a quick smile.

Her face lit up as she returned his smile with a shy half-smile of her own. She looked down at the boots and wiggled her feet in them happily as Kennedy moved on.

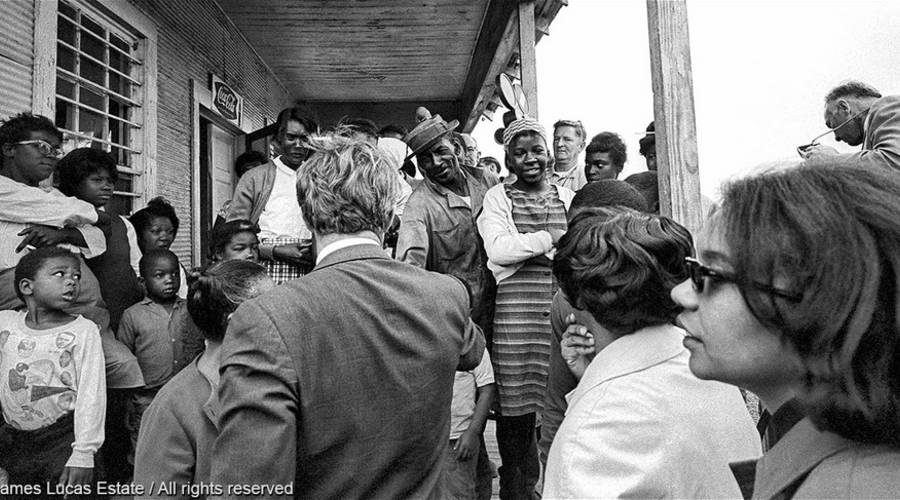

As Kennedy turned to the next house, the editor of the local newspaper, Cliff Langford rounded the corner. Just what, he asked Kennedy, did he think he was doing there?

Journalists gathered around them. Peter Edelman stood watchfully at Kennedy’s shoulder.

“Trying to help people,” Kennedy responded.

Why, Langford asked, didn’t Kennedy and Clark take care of the hunger in their own states?

“I am. Why aren’t you trying to help here?” Kennedy asked.

Kennedy said he had met people in Mississippi and elsewhere who couldn’t get jobs. In fact, Mississippi officials had testified the day before that many people in the state lacked the education and training to get jobs, he pointed out.

At this, Langford interrupted him.

“I think basically most of our colored people here, even though they are very, very poor, some of them, have a lot of pride. They don’t like to take a handout. They’ll scrape around to get a few dollars to buy the food stamps. I think it gives them something to live for, rather than just ‘I’ll become a ward of the government.’ That’s the thing that disturbs us here,” he said.

“Disturbs who?” Kennedy asked with a quizzical look.

“Disturbs the people of this community. We want to help ’em, and we want to see that nobody goes hungry. I have a standing offer from my paper, that anybody who goes hungry, I’ll put food on their table. . . .” Langford said.

Kennedy, with a sly grin, said, “Well, here, I’ll introduce you, . . .” as he gestured and took a step toward the Dillard children.

Once he returned to Washington, Kennedy began immediately seeking ways to help the children he had met in Mississippi. However, institutional obstacles and powerful men who were indifferent to the suffering of poor, black children made getting aid to them much harder than he expected. Kennedy, who had yet to decide to run for president in 1967, spent only a few hours in the Delta, but he could not shake the memories of the children he had seen in Mississippi. He talked about it, even when it wasn’t politic or popular, for the rest of his life.

That spring Kennedy pushed into places others would not go to see poverty for himself. What he found motivated him to work for change in ways that still reverberate today, both in current food-aid policy and in the lives of those he encountered. This book tells the story of his visit, but it also offers much more, for when Robert Kennedy traveled deep into the Mississippi Delta, he took an essential step toward his and the nation’s destiny.