Jordan’s publisher recalls working with the civil rights and corporate leader, who passed away on March 1.

-

Spring 2021

Volume66Issue3

Editor's Note: Peter Osnos was a reporter at the Washington Post and a prominent book editor and publisher in New York. He founded PublicAffairs Books in 1997 and served as its Publisher and CEO until 2005. Mr. Osnos worked with Vernon Jordan while at PublicAffairs, and adapted the following essay for American Heritage from Especially Good View: Watching History Happen, his memoirs being published in June.

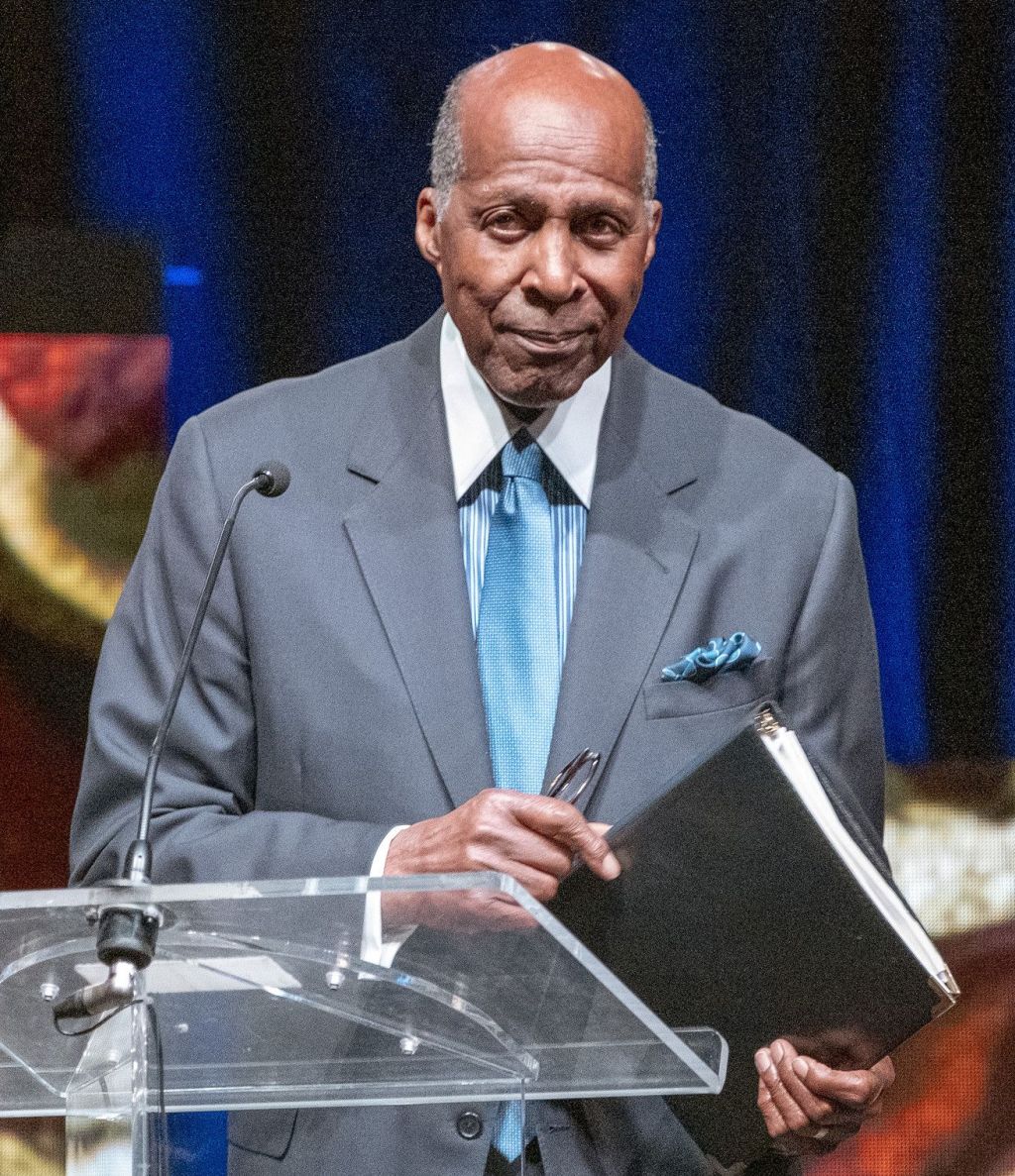

Wherever Vernon Jordan happened to be, he was memorable. With extraordinary charisma, he was a stellar figure in the Washington and New York orbits he inhabited for decades.

What made Jordan different from other personages of the era was that he was so very proud and aware of all that it meant to be Black, his family heritage and his role in the Civil Rights movement. A major figure in the business world and investment banking, he was to Blacks in corporate America what Rosa Parks was to refusing to sit in the back of the bus, as Henry Lewis Gates Jr. of Harvard has said of him.

Jordan came from a simple background in Atlanta. I once visited the modest housing project where he was raised. Jordan went to DePauw University on a scholarship, at a time when there were very few Black students in any white colleges. He received his law degree at Howard University in 1960 and went south to take on, among other things, civil rights cases. He received national attention when he escorted Charlayne Hunter as she enrolled at the University of Georgia in 1961, defying white student outrage and state government resistance.

Jordan, a natural leader, served as executive director of the United Negro College Fund, and from 1971 to 1981 he was president of the National Urban League, one of the major civil rights organizations of that era, with a reputation for determination but not one of the groups that became identified with the Black Power movement. He joined the Washington law firm of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, later became a banker with Lazard Frères in New York, and has stayed in both positions to this day.

Jordan’s arrival in any room was an occasion. He was very tall, extraordinarily handsome, and well attired, and in most places one of the only African Americans on hand as a guest. He told me he would always make a mental list of any other Black people in the room who were not wait staff, and the number was invariably small. His commitment to the civil rights cause was never doubted, and he was the eulogist or speaker at events where the most prominent African Americans of that time were either mourned or honored. Vernon Jordan could and did go anywhere, but he never forgot the color of his skin and what that represented in American history.

On May 29, 1980, Jordan was almost killed when he was shot outside a Holiday Inn in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in the company of a white local woman official of the NAACP. The shooter, a white racist named Joseph Paul Franklin, was acquitted but years later was convicted of murder in another case. In prison, Jordan told me, Black prisoners surrounded Franklin and knifed him repeatedly in the arms and legs. He finally admitted the attempted murder of Jordan.

Jordan amassed an array of corporate directorships, including American Express, Dow Jones, Sara Lee, Corning, and many others. His business successes were matched with his visibility in Washington and New York elite circles. And over time, he became close to the charismatic young governor of Arkansas, William Jefferson Clinton. When Clinton became president, Jordan was one of his closest pals and confidants, sharing golf, gossip, political insight, and the definition of a good time — occasionally, I suspect, to a fault.

Jordan could have had a major position in the administration but preferred the role of outside adviser. That turned out to be a problem when in 1998 he was caught up in the scandal involving Clinton and the intern Monica Lewinsky. Jordan had been tasked to find Lewinsky a job in New York and was generally caught up in the swirl of that tabloid saga leading to Clinton’s impeachment. He testified in various proceedings connected to the scandal and was invariably portrayed as too close to Clinton for comfort on this matter.

That period ended, and Jordan returned to his extraordinarily successful business and active social life. In 1999, he decided he wanted to write a memoir. His literary agent, Mort Janklow, asked publishers for what I was told was a $1 million advance. Invariably, the publishers would ask Jordan whether he was prepared to talk about Clinton, Lewinsky, and other behind-the-scenes Washington tales. His response was to say that everything he had to say on that topic had been given in testimony and Kenneth Starr’s report on the affair. He had nothing to add. The project found no takers.

Among Jordan’s Washington friends and occasional investment partners was Frank Pearl, the chair of Perseus Capital, Perseus Books, and therefore the majority shareholder at PublicAffairs, the publishing company I founded after I left Random House. Frank suggested that I meet with Jordan. The book Jordan wanted to write would be called Vernon Can Read! The title came from the exclamation of the retired head of the Bank of Atlanta, who one day in the summer of 1955 discovered the twenty-year-old Vernon Jordan, a summer hire as driver and waiter, engrossed in a book in the banker’s library.

The banker had never seen a Black person reading before. Jordan wanted his memoir to describe his youth and his civil rights work and to end with his departure from the Urban League for his life in big-time law, banking, and business.

I said that we would be proud to publish that book and made an offer of about 10 percent of what Janklow had been seeking. We made the deal. One afternoon perusing the shelves at the celebrated Washington bookstore Politics and Prose, Jordan came upon Annette Gordon-Reed’s book Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, which showed conclusively that Jefferson had had a long sexual relationship and children with Hemings, his slave. Jordan called Gordon-Reed, introduced himself, and said he’d like her to write his memoir with him.

She was then a young law professor and readily agreed. She later moved to Harvard Law School, and for another book on the Hemings family she won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

The editor for Vernon Jordan’s book was Paul Golob, whose style and skill suited the two authors as it had suited Jimmy Carter and so many others. When the writing started to arrive, Paul and I agreed that it needed to more closely reflect Vernon’s voice and personality and how he developed his stunning ability to transcend every social barrier without ever losing his core commitment to racial justice.

The four of us would assemble around a table at the PublicAffairs offices and talk through each chapter. On arrival, Vernon would make his way past the desks with warm greetings to everyone by name. I was seeing charisma at its best. Over time we enlivened the stories, not by changing them but by making them feel personal rather than descriptive. We questioned Vernon about how he really felt about the experiences that needed texture and context, and as he began to trust us, the book took shape.

When the manuscript was finished, Vernon organized a celebratory lunch at the Rockefeller Center executive dining room of Lazard Frères. The menu was embossed with the jacket art, and all those who had worked on the book were invited. To his right, Vernon seated Darrell Jonas, my longtime assistant.

On release, Ebony magazine called it “an inspirational life story.” Other reviewers were more enthusiastic. Vernon’s television interviews were excellent and his appearances, especially at his family’s church in Atlanta, were dazzling.

The Clinton issues were never raised. The book made bestseller lists. It was in every way a pleasure. I later published a second book with him, Make It Plain: Standing Up and Speaking Out, a collection of his eulogies and speeches. When it was time to mark the twentieth anniversary of PublicAffairs with a televised panel at Politics and Prose, I invited Mr. Jordan to do the introduction. Here is some of what he said, which conveys the many strands of Vernon’s personal philosophy:

Thank you, Mr. Jordan.