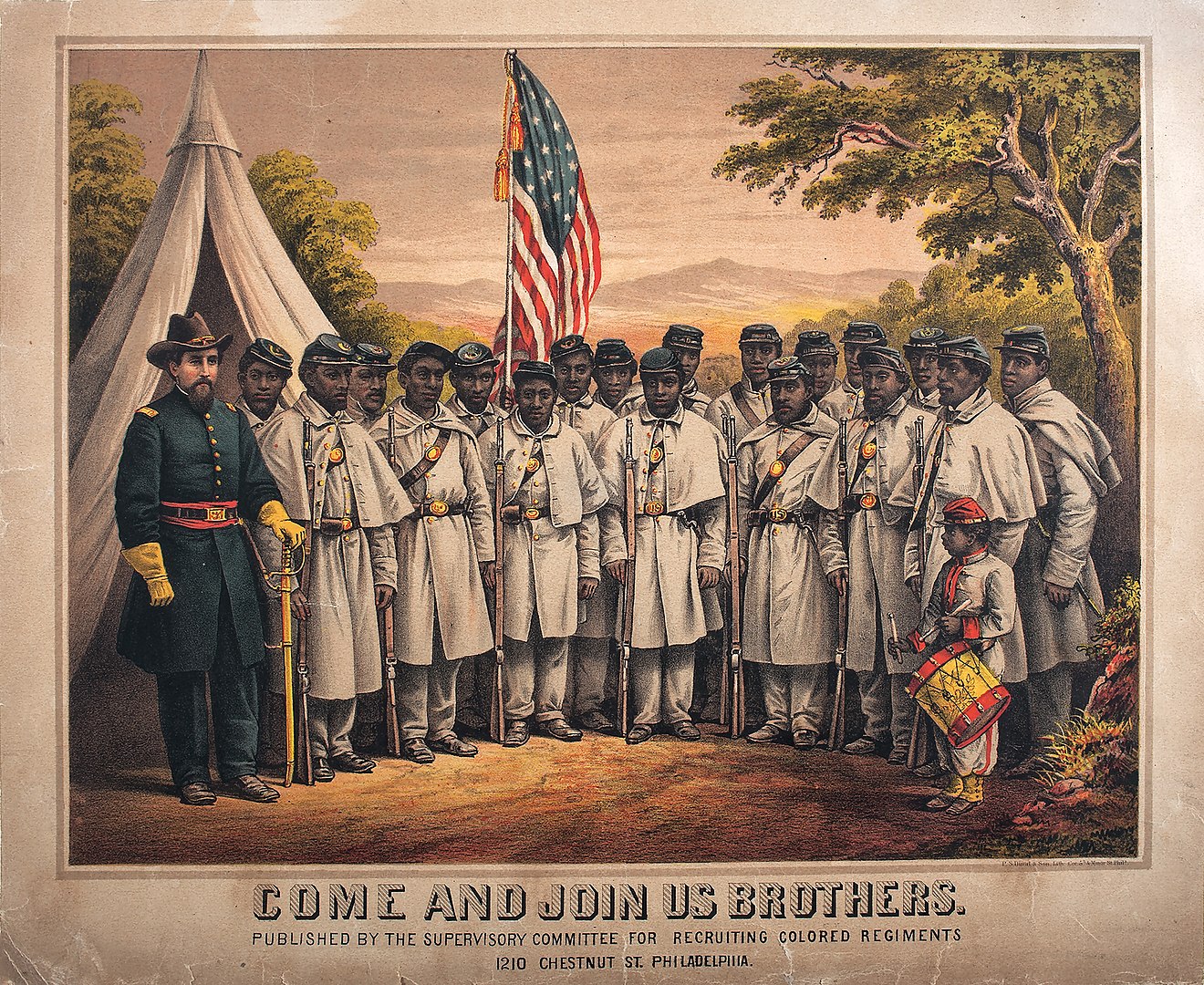

By the end of the Civil War, nearly 200,000 African-Americans had fought for the Union cause and freedom

-

Summer 2010

Volume60Issue2

The American Civil War had cost more than 620,000 lives and had nearly torn the nation apart, but by May 1865 it was finally over. To celebrate, thousands of people gathered in Washington, D.C., to express their gratitude to the military forces that had made the Union victory possible. More than 200,000 Union troops paraded through the city in this Grand Review—but only white troops participated. Even though more than 185,000 African American soldiers had served the Union cause and suffered disproportionately high casualty rates in battle, black soldiers were not invited to the Washington celebration.

Several months later, the citizens of Pennsylvania, a state that had sent 11 black regiments to the war, tried to make up for that injustice. On November 14 the city of Harrisburg hosted its own Grand Review of black troops in the Pennsylvania capital. Thomas Morris Chester, the city’s most distinguished African American, served as grand marshal.

He had served as a war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press and had reported firsthand about the roles played by black fighting men. “This land of our birth is, if possible, more endeared to us, and rendered ours more rightfully by the courage of the colored soldiers in its defense,” he wrote.

The war in which those men had defended their country arose from generations of unsuccessful efforts to deal with the nation’s most critical contradiction: the presence of slavery in a land that had declared its commitment to human freedom in the Declaration of Independence. By the mid-19th century, American slavery had become a significant part of the national economy, although it was largely concentrated in the South, where almost 4 million blacks lived in bondage. By midcentury the "Free Soil" movement had emerged from the efforts of free blacks and their white abolitionist allies in the North to prevent slavery from expanding into the western territories. The Republican Party, founded in 1854, opposed slavery’s spread, but Republicans did not fight vigorously against the institution where it already existed.

Most white Southerners interpreted Lincoln’s election as a threat to slavery, their central economic and social institution. In December 1860 South Carolina issued a proclamation of secession, quickly followed by the secessions of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. In February 1861 these seven states formed the Confederate States of America, a new nation constructed to protect individual property rights, especially those of slaveholders. Weeks later Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina also threatened to secede. Many free African Americans in the North welcomed these developments, believing that Southern secession would remove slavery from the federal government’s protection. H. Ford Douglass, a former Virginia slave, expressed the feelings of most Northern blacks. “Stand not upon the order of your going,” he challenged, “but go at once . . . there is no union of ideas and interests in the country, and there can be no union between freedom and slavery.”

President Lincoln reacted cautiously to Southern secession. In his inaugural address in early March 1861 he firmly opposed the right of states to secede. Yet he reassured slaveholders by saying, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” Nevertheless, on April 12, 1861, Confederate batteries in Charleston Harbor opened fi re on the federal Fort Sumter and launched the first combat of the Civil War. Lincoln immediately

Within days approximately 475 Pennsylvania volunteers set out from Harrisburg for Washington, D.C., to protect the nation’s capital. Among these “First Defenders” was Nicholas Biddle, a 65-year-old man who had escaped slavery in Delaware, took refuge in Philadelphia, and finally found employment as a servant in Pottsville. He had an interest in the city’s militia units, but Biddle could not enlist as a soldier because he was black. Still, he served as an aide to Capt. James Wren, the commander of an artillery company, and he marched with the men when they left for Washington. On the way through Baltimore, a mob attacked the soldiers. One of the rioters hurled a brick that struck Biddle in the face, making him “the first man wounded in the Great American Rebellion,” as a wartime photograph described him.

Some African Americans in Northern cities such as Pittsburgh, Boston, and New York had already formed military units. They saw the war as a means to end slavery, but the U.S. military would not accept their service. Many white Americans questioned their courage and military ability, and Lincoln resisted black enlistment. African Americans saw this rejection as a racial prejudice that ignored their past contributions to the nation. “Colored men were good enough . . . to help win American independence,” noted abolitionist spokesman and former slave Frederick Douglass, “but they are not good enough to help preserve that independence against treason and rebellion.”

By 1862 the war’s staggering casualty rate and early Union defeats convinced Lincoln to reconsider his thinking. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which authorized the recruitment of African Americans into Union forces. As a result, substantial numbers of black troops entered the U.S. military. Joseph E. Williams, a black Pennsylvanian, traveled to North Carolina and recruited former slaves to serve “as men in the defense of the Republic.” Speaking for many of the troops he raised, Williams observed, “I will ask no quarter, nor will I give any. With me there is but one question, which is life or death. And I will sacrifice everything in order to save the gift of freedom for my race.”

Yet race played a major role in the African American war experience. White officers commanded the black units. Black recruits received roughly half the pay of whites at the same rank. Black troops were also particularly vulnerable in combat, as Confederate forces took few blacks as prisoners and executed most black captives. One atrocity occurred in the spring of 1864 at the battle for the Confederate Fort Pillow in Tennessee. Only 62 of the original 262 African American troops survived. Many were killed after the fighting ended because Southern Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan after the war, ordered his soldiers to kill captured blacks. “Remember Fort Pillow” became a rallying cry for many Union soldiers.

Perhaps this helped to convince the federal government to finally equalize African American military pay, supplies, and medical care. In the South, African American slave labor produced most of the food supplies for the troops, and the Confederacy impressed both free blacks and slaves into service as laborers, teamsters, cooks, and servants to support the military.

Early in the war, Louisiana’s Confederate government sanctioned the Louisiana Native Guards, a militia unit formed by free blacks. Confederate authorities used the unit for public display and propaganda purposes, but it did not fight for the Confederacy. Instead, when Union forces invaded Louisiana and recruited Southern blacks to their ranks, at least 1,000 troops of the Native Guards joined the Union army. In late September 1862 they became the first officially sanctioned African American unit in the Union forces.

By the end of the war in 1865, some 200,000 blacks had served the Union cause. Twenty-five of them, including William Carney, Thomas Hawkins, and Alexander Kelly, received the Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery.