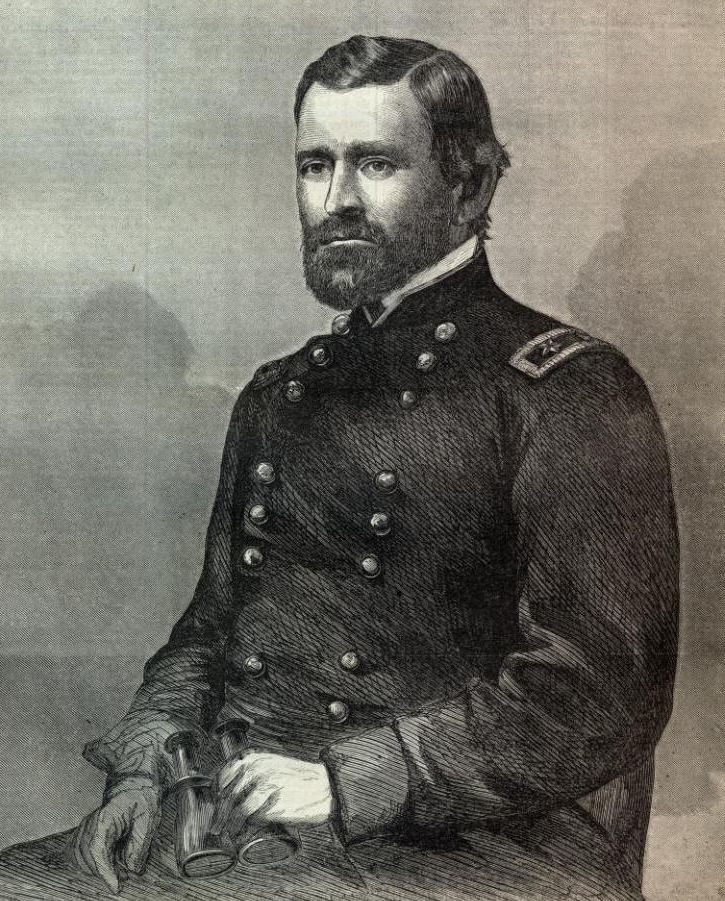

With his command threatened by allegations of drunkenness, Ulysses S. Grant went on the attack, won two major victories, demanded “Unconditional Surrender”, and nearly split the Confederacy in half.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

The North started winning the Civil War in January 1862, but nobody knew it yet. Hindsight hadn’t had time to kick in. Plus it happened out in the middle of America, far from the conflict’s media-massed Virginia front yard. And the man who would lead the victory, from western Appalachia all the way to Appomattox in 1865, was the unlikeliest candidate then imaginable.

The West Point credentials of President Lincoln’s top commanders in late 1861 belied any intent of attacking the enemy. In front of Washington City, egocentric General-in-Chief George McClellan preened in dread, training and equipping the already first-rate Army of the Potomac while studiously avoiding combat with the undermanned Confederate States of America. He was outnumbered, he claimed.

In Kentucky, Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell acted similarly with his Army of the Ohio. Like McClellan, Buell ignored Lincoln’s orders to advance. And in St. Louis Lincoln’s other western chief, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, kept to the Planter House hotel and dispatched minions to chase guerrillas across Missouri. More focused on army politics than war, Halleck and Buell appeared determined to force the other to risk making the first mistake.

Enter an unloved Halleck subordinate.

Ulysses S. Grant was an accidental brigadier general. When the war broke out, despite being a West Pointer and a veteran of the Mexican War, he barely got back into the army. Conventional military wisdom labeled him a sot. He had bailed out of the prewar U.S. regulars in 1854 under rumored threat of charges of drunkenness on duty—resigning, a friend later said, rather than have his wife find out. A couple of years later, ex-comrades saw him in shabby clothes on St. Louis street corners peddling firewood. Asked to explain, he said, “I am solving the problem of poverty.”

By any peacetime measure, Grant had been at best a middling officer. He had attended West Point unwillingly, cared little for his studies there, and possessed no martial ambition or pride in the uniform. Post graduation, he served in the antebellum army for 11 years because he saw nothing more promising to do. He rose only to the rank of captain—in part, no doubt, because his birth, compared to the upper-crust West Pointers of his era, had been humble. His father was a tanner.

So when the war came, he was ignored. He managed to re-enter the army only when the governor of Illinois named him to replace a colonel who had been unable to handle the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Yet within two months, the new colonel found himself a brigadier general, thanks to an Illinois congressman who wanted as many Illinois generals as he could get.

Grant soon commanded a 20,000-man army in the military district of Cairo, Illinois, which sat on the state’s southern tip looking down the Mississippi River. As the nation’s primary commercial highway, the Mississippi was a top Union preoccupation. Retaking its Confederate half would regain Federal sway over the center of America, splitting Dixie.

But in January 1862 Grant’s Cairo post was in jeopardy. First, his commander, Henry Halleck, who had no confidence in him, worked mightily to get a retired colonel friend leapfrogged to major general to take Grant’s place. Then, a civilian subordinate and temperance fanatic filed allegations of drunkenness against him. The charges screamed that Grant had imbibed with Confederates—“traitors”—on a flag-of-truce boat; had gotten “beastly drunk” and “incapacitated for business”; and had engaged in “Conduct Unbecoming an Officer and a Gentleman.” (It was later learned that the plaintiff may well not have even been in Cairo when the incidents he alleged occurred.)

Grant likely had no firm knowledge of Halleck’s effort to promote a friend to take his job, but he probably suspected it. He certainly knew of the drunkenness charges, because Halleck sent them to him for his signature as district commander.

Grant had to do something fast to hang onto his army, and within a week he did. He joined naval Flag Officer Andrew Foote in requesting that they be allowed to launch a joint attack by land and water on two hastily built Confederate forts facing each other across the Tennessee River just south of Kentucky’s Tennessee border.

The timing was fortuitous. To one-up Buell in army politics, Halleck needed to push southward, and he approved the Grant-Foote proposal. The two got moving before Halleck could change his mind.

A Confederate fortress on a Mississippi River bluff 20 miles south of Cairo at Columbus, Kentucky, stymied Union operations down the Father of Waters. But taking Fort Henry and Fort Heiman on the Tennessee would avoid Columbus and the Kentucky “Gibraltar.”

Grant and Foote departed on February 3. Three days later they were on the verge of attack. An overnight downpour turned the roads to mud, slowing Grant’s infantry but not Foote’s gunboats. Four ironclads and three other vessels doubly sheathed in timber battered and captured Fort Henry in two hours before Grant’s 17,000 infantrymen arrived. The Confederates had already abandoned Fort Heiman.

All but about 100 of the forts’ nearly 3,000-man Confederate garrison escaped, fleeing 12 miles to Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. They joined other Confederates concentrating there. But the Union victory that day was complete. Within 24 hours, Federal gunboats raced the breadth of Tennessee into Alabama and Mississippi. Dixie had been split wide open.

Grant, though, had a problem. He had taken possession of an all-but-empty fort, and Foote’s gunboats, not Grant’s infantry, had made the capture. Grant’s job security demanded more than this, and he immediately messaged Halleck that he would move to take Fort Donelson. But downpours continued. Marching an army cross-country was impossible, and reconnaissance revealed Donelson to be a harder target than Henry. It occupied a 100-foot hill, was filling up fast with Confederates, and had trenches that stretched more than two miles, fronting both the fort and the village of Dover. Another complication arose: Halleck had not responded to Grant’s declaration of his intention to take Donelson.

On the afternoon of February 11, the rain stopped and Grant got one division heading east toward Fort Donelson. Two more divisions—about 15,000 men—followed the next day. The columns were strung out on two roads across hills and woods, vulnerable to attack, but Grant had served in the Mexican War under the man commanding Fort Donelson and had little respect for his military instincts or ability. In fact, Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow had been widely considered a laughingstock.

Meeting only light opposition, Grant took his men to the foot of the Confederate trenches. He spent February 13 surrounding Donelson’s landside, only to realize he had too few men to complete the task. So he waited. Foote’s gunboats were en route. They had had to go back down the Tennessee to the Ohio, then up the Cumberland to Donelson.

The ironclads were Grant’s trump card. The metal-sheathed gunboats were a war-changing innovation pioneered in Europe in the late 1850s, and Foote’s battering of Fort Henry had left the Southerners thunderstruck. Grant expected the ironclads to overwhelm Donelson, too. So did the Confederates. Nobody, however, had factored in the terrain. At river-level Fort Henry, Foote had been able to fire straight on as he approached, but at Fort Donelson, on a hilltop, the advancing gunboats would have to continually raise the elevation of their guns, a difficult maneuver for maintaining accuracy.

The boats arrived late in the afternoon, escorting transports carrying 6,000 more infantrymen. Grant—having just received orders from Halleck to dig in at Henry, not Donelson—nevertheless urged Foote to attack the next day. Foote did so. Donelson’s Confederate gunners all but blew the gunboats out of the Cumberland. Foote himself was wounded. His crews had to spread sand on their decks to keep from slipping in the blood. After a two-hour fight, with their steering mechanisms wrecked, the boats managed to drift back down to a protective bend. They had killed or wounded not a single Confederate gunner.

Grant’s trump card had proved a joker. And now the previously balmy weather vanished. Temperatures plunged to 12 degrees in wind-whipped snow. Grant’s men were without tents or adequate clothes. Overnight Foote sent Grant a request to see him; his wound, he said, did not permit him to come to Grant. Very early on February 15, Grant set off on horseback to Foote’s mooring several miles away. At the meeting Foote told Grant he was taking the crippled ironclads home for repairs. He expected to be back in 10 days. Grant urged him to leave one or two of the still potent gunboats behind. Foote agreed, and soon the meeting ended.

When Grant stepped back on the riverbank from Foote’s flagship, he received bad news. He had left no one in charge of his lines that morning and the Confederates had broken out in front of Dover and were steamrolling his army’s right and pushing toward the center. He rode back as fast as possible over the icy road.

He arrived at his right-center in early afternoon to find a bewildering sight. His right was crushed and his right-center in disarray, yet the Confederate assault that had raged from 6 a.m. until 1 p.m. had unaccountably halted. The Confederates were withdrawing into their trenches. Unknown to Grant, Pillow had ordered the Southern troops back. The attack had been designed to open a road for escape to Nashville and, Pillow said later, he called them back to collect their gear and march out.

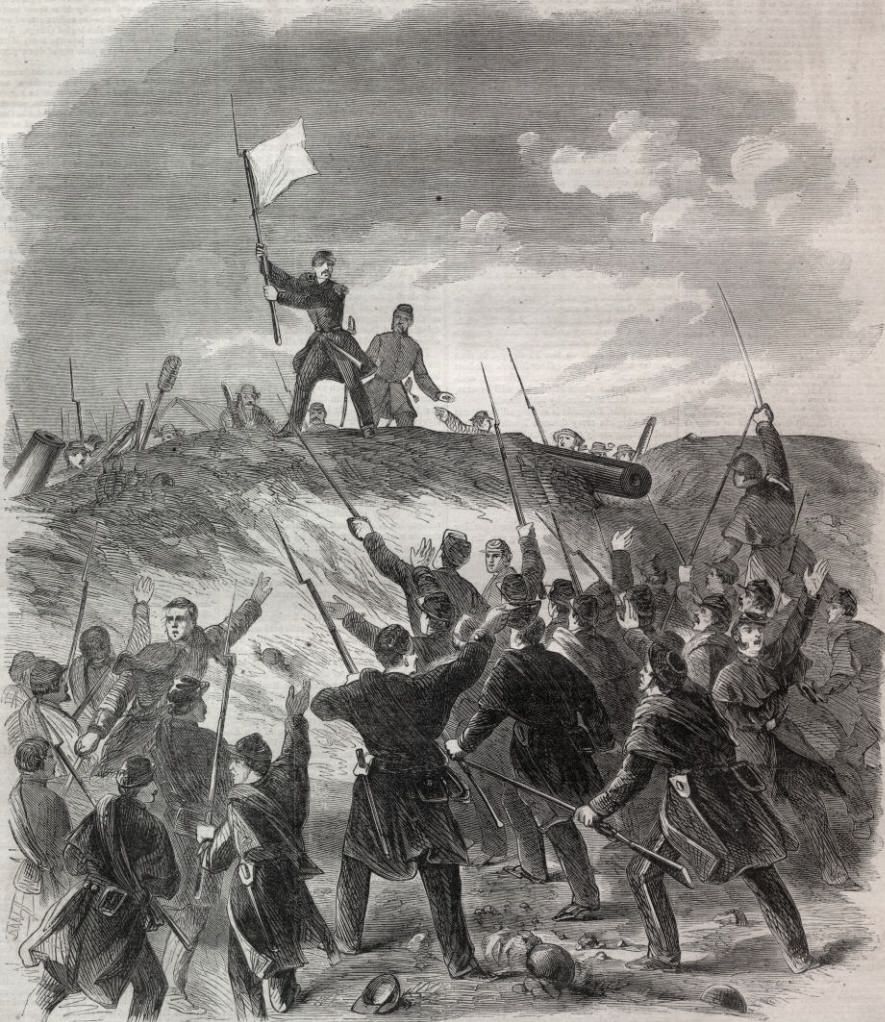

Grant correctly analyzed the situation—and more. The Confederates were exhausted after the morning-long attack. And to make the all-out assault on his right, they would have had to pull most of their troops away from the trenches in front of his left. Teeth clenched on the stub of a cigar Foote had given him that morning, Grant ordered a counterattack all along his line, beginning with the left. As he had predicted, Federals soon battled their way into undermanned Confederate trenches. As dusk fell, they hauled up field guns.

The Union lodgment in the trenches induced a bizarre, almost comedic surrender—because on February 13, Pillow had been superseded by a new, even worse Confederate commander, former U.S. Secretary of War John Floyd. Fearing he would hang if captured, Floyd abruptly returned command of Donelson to Pillow, who refused it. He passed it instead to an antebellum friend of Grant’s, Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, who counseled capitulation. Floyd then commandeered a steamboat and fled with some of his troops, while Pillow and an aide escaped in a skiff. Buckner sent a message to Grant requesting terms, to which Grant memorably replied: “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.”

Overnight, Lincoln promoted Grant to major general, and Northern newspapers made “Unconditional Surrender” Grant a sensation. He had captured a Confederate army of nearly 15,000 men. His battlefield cigar became famous; admirers began sending him so many boxes that he gave up his pipe.

Grant focused on harvesting the fruits of Henry and Donelson. Dixie had been split all the way to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. His Federals wrecked a Tennessee River railroad bridge that was the connection between the Confederate left at Columbus, Kentucky, and the right at Bowling Green. To prevent being outflanked, the Southerners were scrambling backward across Tennessee into Alabama and Mississippi. Loss of Columbus loosened their grip on the southern half of the Mississippi River.

Grant saw an opportunity to press the Union advantage. His superiors did not. Halleck was busy playing intra-army politics, demanding authority over the entire western theater as reward for Grant’s victory. He meanwhile held back Grant and Foote, letting the cautious Buell take a week to occupy Confederate-abandoned Nashville. When Grant then journeyed there to assess matters and perhaps hurry things up, Halleck complained that his suddenly famous subordinate had gone without permission, had been laggard in filing reports, and seemed to have returned to “old habits.” He suspended Grant.

Lincoln quickly gave Halleck command in the West. Only then did Halleck return to focusing on Confederates. The next obvious goal was the rail hub of Corinth in northern Mississippi. Halleck sent Grant’s old army southward on the Tennessee River to just north of the Mississippi border. In mid-March, though, the Lincoln administration inquired into what had happened to the Fort Donelson victor, and Halleck hastily gave Grant back his command. Halleck implied to Grant that he had saved him from enemies further up the chain.

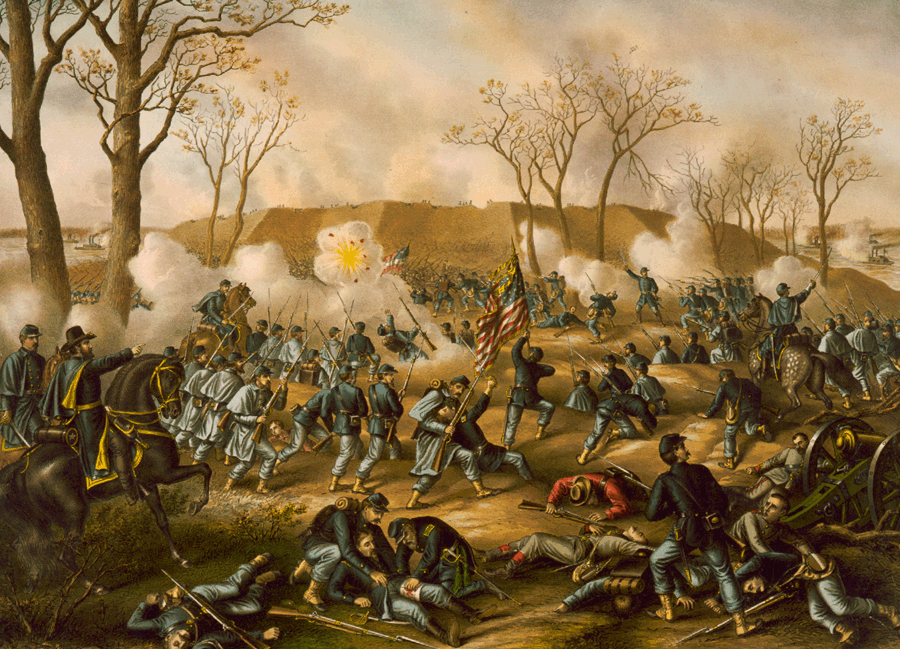

Less than a month later, a massive Confederate counterattack nearly drowned Grant’s army in the Tennessee River. Though he refused to admit it, Grant was surprised—in fact, astonished—that the Confederates had left their Corinth fortifications to attack him.

Much of the fault was his, but not all. Halleck had told him that he, Halleck, would come down from St. Louis to direct the Corinth campaign. He would lead both Grant’s army and that of Buell, who was coming cross-country from Nashville to join Grant at Pittsburg Landing. Halleck ordered Grant not to initiate a battle before he arrived.

So Grant and a new friend, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, ignored Confederates gathering around them. They threw up no defenses at Pittsburg Landing, positioning their 40,000 troops conveniently near water. Sherman himself camped near a rough-hewn church called Shiloh.

Forty-four thousand Confederates under generals Albert Sidney Johnston and Pierre G. T. Beauregard struck at breakfast on April 6. Vicious fighting drove the Federals out of their camps. The Confederates, having exhausted their rations the day before, stopped to wolf the food they found cooking on Federal campfires. The contest seesawed, with Sherman and other Federal commanders sometimes rolling the attackers back. By early afternoon, thousands of Federals had fled to the bank of the Tennessee River. But troops under Union generals Will Wallace and Ben Prentiss formed a line in the center of the battlefield along a slight depression made by an old farm road. Grant ordered them to hold that line, and they did through most of the afternoon, helped by the Confederate’s concentration on the Federal flanks. But an hour before dusk, with Wallace mortally wounded, Prentiss and 2,000 survivors surrendered. Still, they had bought valuable time for Grant’s army.

Grant was able to position a last line of more than 50 cannon to keep the Confederates from reaching Pittsburg Landing. All afternoon he had awaited the arrival of a division under Lew Wallace, camped a few miles north near Crump’s Landing. But now, at nearly dark, it was part of Buell’s army that arrived on the far side of the Tennessee and began ferrying across. Wallace’s column also finally showed up, having taken a wrong road.

That night in a hellish rain, a battle-bloody Sherman approached Grant to recommend a retreat across the river. “Well, Grant,” he began, “we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”

“Yes,” Grant agreed, then blocked further negativity: “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.” The Confederates were fought-out, he explained. Fort Donelson had shown that the side with the grit to make a final forward push would win.

The next day he pushed—and won. Gen. Johnston had been killed on the field, and Beauregard ordered a Confederate retreat in mid-afternoon of April 7. Buell afterward claimed that his army had saved Grant’s, but only a dozen Buell companies made it across the river before darkness ended the first day’s fighting. His troops did fatten Grant’s counteroffensive on April 7, but by then, the Confederates were in the process of reorganizing units that had gotten mixed and confused in the fighting.

America had never seen such blood. Shiloh’s casualties—1,700 killed and 8,000 wounded in each army—were horrifying, and some critics blamed Grant. Unlike other generals on both sides, Grant never drank near a battlefield, but predictably he was accused of drunkenness. Shaken, he falsely claimed the Confederates had far outnumbered him.

Halleck, ever cagey, refused either to blame Grant or to back him up. Halleck also didn’t mention that he himself should have been there. He did get there quickly in the aftermath, however, only to do what he had done after Fort Donelson: allow the Confederates time to regroup.

First, he amassed a host of more than 100,000, combining Grant’s army with Buell’s and Maj. Gen. John Pope’s. Then he tightened bureaucratic efficiency. He made Grant his second in command, with so few duties that Grant resolved to go home—until Sherman talked him out of it.

Finally, at the beginning of May, Halleck headed his huge force off to face 70,000 Confederates Beauregard had gathered at Corinth. Determined not to be surprised, Halleck ordered his army to entrench each night, and thereby averaged less than a mile a day. He spent a full month covering the 20 miles to Corinth—and found it abandoned. Beauregard had gathered his men and materiel and withdrawn 50 miles to Tupelo.

Yet again, Halleck provided the Confederates precious time. He spent June building huge fortifications around Corinth. He also split his horde into three armies and scattered them, placing Grant and Pope on glorified guard duty and sending Buell across Alabama toward Chattanooga.

Exhibiting no sense of urgency, Halleck saddled Buell—who already suffered from what Lincoln wryly dubbed “the slows”—with repairing the Memphis and Charleston Railroad as he went. This allowed the new Confederate commander at Tupelo, Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg, time to move the bulk of his army from Tupelo to Chattanooga and dig in before Union forces arrived.

Had Halleck sent Buell to Chattanooga with the single aim of arriving there first, Grant later theorized, Buell could have captured that important rail hub with scant loss. But Halleck’s first priority, Grant believed, should have been opening the Mississippi all the way to New Orleans. After taking Corinth, he should have put a sizable army on the road to Vicksburg, whose capture would be for the Confederates, according to Grant, the “amputation of a limb”—and would complete the splitting of Dixie.

Fortunately for the Union and its ultimate victory, Lincoln called Halleck out of the field and back to Washington, leaving Grant the West’s highest-ranking general. The army’s lassitude quickly disappeared, and Ulysses S. Grant began eyeing Vicksburg.