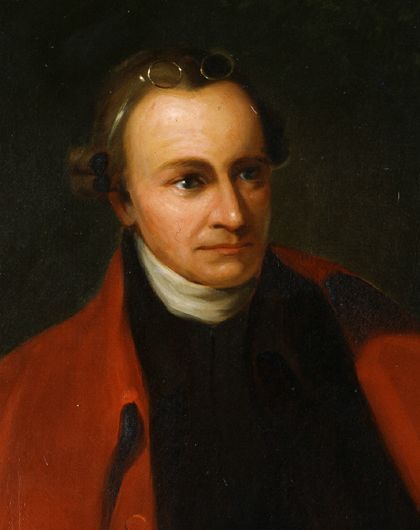

It has been called one of the most consequential debates in American history. The Revolution's greatest orator later fought to stop ratification of the Constitution because of his worries about powers proposed for the Federal government

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

Under the Articles of Confederation, these United States were barely united. Unable to agree on either foreign or domestic policy, they sank into economic depression. In May 1787, delegates from twelve states (Rhode Island sent none) arrived in Philadelphia to define a new federal government. In September, they had a new constitution.

But for the Constitution to become law of the land, conventions in nine states had to ratify it. By June 1788, eight states had done so. Anti-Federalists, as opponents of the new Constitution came to be called, saw the Virginia ratifying convention of June 1788 as their last stand.

The leading Anti-Federalist in Virginia was Patrick Henry, who was generally acknowledged as the Revolution's greatest orator. The leading Federalist in Virginia, indeed in all the United States, was James Madison, generally acknowledged as the founder most responsible for the Constitution.

"Even more than the Lincoln-Douglas debate over slavery, or the Darrow-Bryan debate over evolution," writes historian Joseph Ellis, "the Henry-Madison debate in June of 1788 can lay plausible claim to being the most consequential debate in American history."

WILLIAM WIRT, IN HIS 1817 BIOGRAPHY OF PATRICK HENRY, described how the twenty-nine-year-old delegate addressed the Virginia House of Burgesses in May 1765 to protest the Stamp Act. Wirt described how Henry, "in a voice of thunder, and with the look of a god," declared that "Caesar had his Brutus—Charles the First, his Cromwell—and George the Third...may profit by their example." Interrupted by cries of "Treason," Henry responded, "If this be treason, make the most of it."

Among those who witnessed Henry's speech in Williamsburg was Thomas Jefferson, then a twenty-two-year-old law student and later Madison's close friend and political ally. Jefferson admired the power of Henry's oratory, but he despised the man. "His imagination was copious, poetical, sublime," Jefferson wrote, "but vague also. He said the strongest things in the finest language, but without logic, without arrangement, desultorily." More bluntly, Jefferson described Henry as "all tongue without either head or heart."

In 1777 Henry clashed with Jefferson—and Madison—over the relationship between church and state. Henry wanted people to pay taxes to support a church of their choice. Compared to having an official state church, as the Virginia colony once had, this was certainly a step toward freedom of religion. Jefferson and Madison wanted a more complete separation of church and state; they argued that churches did not need and should not receive any taxpayer money. Jefferson drafted a "bill for establishing religious freedom" in 1777. In 1785, by which time Jefferson was in France serving as America's ambassador, Madison managed to push aside Henry's proposal for taxes to support churches and push through the Assembly a revised version of Jefferson's bill.

Despite being outmaneuvered on the church-state issue, Henry wielded great power in the Virginia legislature. He successfully blocked efforts by Jefferson and Madison to revise Virginia's 1776 constitution. From Paris, a frustrated Jefferson wrote Madison: "While Mr. Henry lives, another bad constitution would be formed, and saddled forever on us. What we have to do I think is devoutly to pray for his death."

The fight over Virginia's constitution foreshadowed the battle over the new federal constitution. For Madison, the flaws of Virginia's constitution paled beside those of the Articles of Confederation, and those flaws prompted Madison to take the lead in creating the new U.S. Constitution.

"You give me a credit to which I have no claim," Madison later wrote, "in calling me 'The writer of the Constitution of the U.S.'... It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands."

But there was no question that Madison influenced the document more than anyone else.

Madison also led the fight for its ratification. Along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, he published a series of essays defending the Constitution. Jefferson described the Federalist, as the essays were called, as "the best commentary on the principles of government which ever was written."

Henry was among those the Virginia Assembly selected to attend the constitutional convention in Philadelphia with Madison. He declined. "I smelt a rat," Henry reportedly said. Madison hoped he might bring him around, and George Washington wrote Henry that the Constitution was "the best that could be obtained at this time."

Henry quickly squelched their hopes. "I have to lament that I cannot bring my mind to accord with the proposed constitution," he replied to Washington. "The concern I feel on this account is really greater than I am able to express."

Henry had no problem expressing his concerns when the Virginia ratifying convention convened in Richmond. His opening speech made clear the stakes. "I conceive the Republic to be in extreme danger," he exclaimed. "If a wrong step be now made, the Republic may be lost forever. If this new government will not come up to the expectation of the people...their liberty will be lost, and tyranny must and will arise."

Henry challenged the premise of the Constitution's opening words. "What right had they to say, We, the People?" he asked of the Philadelphia delegates. "Who authorized them to speak the language of, We, the People, instead of We, the States? ...The people gave them no power to use their name."

The delegates had been sent to Philadelphia, he stressed, to amend the Articles of Confederation, not to create an entirely new constitution. Nor was there any need for a new constitution. There was no crisis, Henry insisted, at least in Virginia: "Disorders have arisen in other parts of America, but here, sir, no dangers, no insurrection or tumult, has happened—everything has been calm and tranquil."

Madison could not match Henry's passion—in fact, the convention's stenographer complained Madison spoke so quietly he could barely be heard—but he was logical and systematic. He repeated many of the arguments set forth in the Federalist, stressing that the powers of the new federal government would be limited by the states and that the power of the president would be checked and balanced by the powers of Congress and the courts. "The powers of the federal government are enumerated," he explained. "It can only operate in certain cases."

Henry did not buy it. Again and again he rose to speak; over the course of the three and a half weeks the delegates met, Henry spoke nearly one-quarter of the time.

He reminded his fellow Virginians of his stance against the Stamp Act: "Twenty-three years ago was I supposed a traitor to my country," he said. "I may be thought suspicious when I say our privileges and rights are in danger...But, sir, suspicion is a virtue, as long as its object is the preservation of the public good."

Henry suspected that at least some of those behind the Constitution had an ulterior motive. "When the American spirit was in its youth...liberty...was then the primary object," he said. "But now...the American spirit...is about to convert this country Unit() a powerful and mighty empire....There will be no checks, no real balances, in this government."

In his final speech at the ratifying convention, Henry extended the stakes beyond America to the world; indeed, the heavens:

At about this point, the stenographer noted, "a violent storm arose, which put the house in such disorder, that Mr. Henry was obliged to conclude." Archibald Stuart, a delegate to the ratifying convention, described Henry as "rising on the wings of the tempest, to seize upon the artillery of heaven, and direct its fiercest thunders against the heads of his adversaries."

The artillery of heaven was not enough. The next day, June 25, the convention voted 89-79 to ratify the Constitution.

Henry took some satisfaction in the fact that the ratifying convention recommended forty amendments to the Constitution. These were not binding, since Virginians could not force other states to go along with them. But the ratifying convention's recommendations surely added to the pressure to amend the Constitution.

Henry also gained some revenge later that year, when the Virginia Assembly chose the commonwealth's first two senators. Madison finished third in the voting, behind two Anti-Federalists backed by Henry. Madison managed to win a seat in the House of Representatives, despite Henry's support for his opponent, the Anti-Federalist James Monroe. (This was the first and last time that two future presidents would run against each other for a seat in Congress.) During the campaign, Madison promised he would support amending the Constitution, and once elected he did just that—introducing the amendments that would eventually become the Bill of Rights and that would guarantee, among other rights, freedom of religion, speech, press, and assembly.

By 1791, Henry had reconciled himself to the Constitution. "Although the form of government into which my countrymen determined to place themselves had my enmity," he wrote Monroe, "yet as we are one and all embarked, it is natural to care for the crazy machine, at least so long as we are out of sight of a port to refit." By 1795, Washington was so convinced of Henry's loyalty that the president asked him to become secretary of state. Henry declined. He had, he explained, eight children by his current marriage, and his finances and health were precarious. But, Henry emphasized, "I have bid adieu to the distinction of federal and antifederal ever since the commencement of the present government, and in the circle of my friends have often expressed my fears of disunion amongst the states."

Jefferson and Madison, meanwhile, were increasingly worried about the power of the federal government and found themselves making some of the same arguments Henry had made for states' rights. The Republican Party they eventually founded cannot be defined as simply the successor to Anti-Federalism; the evolution of both the Federalist and Republican parties was more complicated than that. But there is no doubt that Madison's embrace of Henry's arguments is, as Ellis put it, "one of the richest ironies in American history."

Portions of this essay appear in Paul Aron's book, Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation, co-published recently by Colonial Williamsburg and Sourcebooks.