When the Army arrested a chief of the Ponca Tribe in 1878 for leaving their reservation, he sued the Federal government and won — the first time courts recognized that a Native American had legal rights.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

In the village of Niobrara, the tiny Ponca tribe operates a museum in a one-story community center covered with dark-brown shingles and white trim. The town is located in the Northeast corner of Nebraska, across from North Dakota, where the Niobrara River flows into the Missouri -- a beautiful stretch of water that remains much the same as it was when Lewis and Clark paddled by 210 years ago.

In the community center, the Ponca hold tight to their memories. The tribe’s historian, Vance Appling, eagerly recounts the story of Standing Bear and the “Ponca Trail of Tears,” when the U.S. forced the tribe to relocate to barren land in Oklahoma in 1877. The debate that followed would have a lasting impact on the nation.

“It was easier for the government to move us because we were a peaceful people,” says Appling, whose gray ponytail sways as he slowly shakes his head. “There were more of the Sioux, and they were troublemakers, so the government gave them our land.”

The tiny Ponca tribe had struggled to find a homeland long before whites came to this area. In the 16th century they fled the Ohio valley looking for more peaceful lands, crossed the Mississippi, and settled on fertile hills in what is now northern Nebraska. The Ponca speak a Siouan language and are related to the Omaha and Kansa Indians to the south. They lived quietly along the banks of the Niobrara, growing beans, squash, Ponca gray corn, and fruit trees. Twice a year, the men hunted buffalo, doing their best to avoid contact with the larger, warlike Sioux tribes to the north.

An even greater threat than their neighbors was smallpox brought by early European traders. In the 1750s a French missionary estimated that eight thousand people lived near the Ponca Fort in the center of their homeland. By the time Lewis and Clark stopped there in 1805, the Ponca numbered only a few hundred.

Standing Bear was born in 1829 and learned to hunt, fish, and follow the ways of his people. But events a thousand miles away would dramatically affect his life: in 1854 Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act and later the Homestead Act, which brought a flood of settlers into the area. The Ponca were forced to sign a treaty giving up two million acres and then in 1858 a second treaty reduced their reservation to 100,000 acres. The mills and schools promised by the U.S. government as part of the bargain never materialized. Nor were the Ponca protected from continuing raids by the Sioux. By 1862, white settlers began building a town they called “Niobrara” right on top of the Ponca’s summer corn fields.

Three years later, a third treaty again guaranteed the Ponca their traditional farming and burial grounds, but shortly after the government signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie to end the war with the Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud, giving away the Ponca land to the Sioux. In 1877 the tribe was forcibly removed from their farms, and their homes and farming tools destroyed. They were forced to walk south with no provisions across the width of Nebraska and Kansas – a total of 400 miles – to arid land in what is now Oklahoma. Most of the 710 Ponca on the march were women and children.

As he retold the story of his ancestors’ ordeal, Appling grew visibly more angry, kneading the curved handle of an old wooden cane. “Nine died on the walk including Standing Bear’s daughter Praise Flower,” the historian said, “and when they arrived in Oklahoma, it was too late to plant crops. They lost nearly a third of the people from malaria and starvation.”

Standing Bear himself would later recall those painful days. “At last I had only one son left; then he sickened. When he was dying he asked me to promise him one thing. He was my only son now; what could I do but promise?"

“He begged me to take him, when he was dead, back to our old burying ground by the Swift Running Water, the Niobrara. I promised. When he died, I and those with me put his body in a box, and then in a wagon, and we started north.”

So, honoring his son’s dying wish, Standing Bear and a few dozen of his fellow Ponca re-crossed the plains In the middle of winter, without food or adequate supplies. By the time they reached their Omaha cousins, they were starving and sick. The Chief Iron Eye of the Omaha offered them shelter, but soldiers under Gen. George Crook soon caught up with the Ponca and arrested them for leaving the reservation.

Crook was a tough Army officer who had commanded divisions and then entire corps during the Civil War, fighting at Manassas, Antietam, Chickamauga, Shenandoah, and finally Appomattox. Crook is generally considered the greatest of the Indian fighters. Before and after the Civil War, he led Army troops against the Indians in Oregon, Arizona, and the Dakota Territory, although in 1876, after a battle on Rosebud Creek when his soldiers ran low on ammunition and other supplies, Crook had been unable to reach the Little Bighorn in time to support Custer and his men.

Unlike most other officers in the Army, Crook had sympathy for the Indians. "He, at least, never lied to us,” recalled Red Cloud, war chief of the Oglala Sioux. “His words gave us hope.”

Crook was appalled when he heard the plight of Standing Bear. He had been ordered by Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, to take the Ponca back to Oklahoma territory immediately. "I've been forced many times by orders from Washington to do most inhuman things in dealing with the Indians," Crook said. "But now I'm ordered to do a crueler thing than ever before." Instead of bringing the Ponca back to their reservation in Oklahoma, he took them instead to his headquarters in Fort Omaha (which is now a historic site in the city suburbs.)

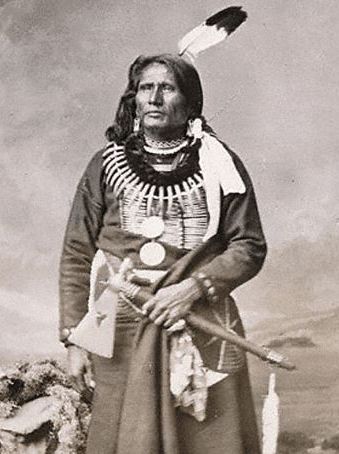

![On the orders of Interior Secretary Carl Schur (upper left), Gen. Crook was ordered to arrest Chief Standing Bear and return him to the Ponca reservation. "I never committed any crime," argued Standing Bear. [But] I was arrested and brought back a prisoner.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Tibbles%20article%20illustration%20of%20SB_0.jpg)

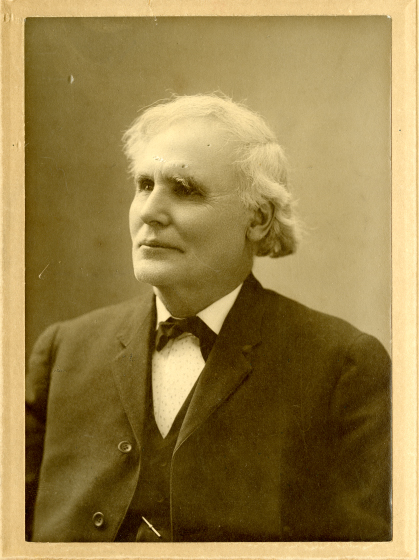

Luckily for Standing Bear, Crook appealed for help to a local newspaper editor, Thomas Tibbles, one of the most remarkable journalists of the 19th Century. The efforts of Tibbles to help the Ponca would change history. In the 1950s, his memoir, Buckskin and Blanket Days, was discovered and published posthumously.

This remarkable frontierman was born in Ohio in 1840. But his father died from fever when Thomas was 11 and the boy was bound out as an apprentice to an unusually cruel master, which gave him a lifelong hatred of slavery and injustice. Thomas ran away and lived on his own doing odd jobs, and in 1856 joined a wagon train of Free Soil pioneers headed to what would soon be called Bloody Kansas. He joined the anti-slavery forces, became an aide to Gen. James Lane, was ambushed by the pro-slavery Border Ruffians, and then saved by John Brown, whom he later accompanied on a raid to free 17 slaves in Missouri.

Tibbles was captured again by Ruffians who sentenced him to death for fighting against slavery, put a rope around his neck, and were hanging him from a tree when some of Tibbles friends surrounded and shot up the Ruffians, freeing the young man.

Tibbles had had enough of Bloody Kansas, and left for the prairie wilderness. He became a paid hunting scout, and then lived with the Omaha Indians. The adventures he had, if his memoirs are to be believed, were much more dramatic than those of the Kevin Costner’s character in the movie Dances with Wolves. Tibbles learned the Omaha language, and even taught them to waltz. He claims he was an amazing shot and always killed more turkeys or other game than the Indians, once shooting seven buffalo on a hunt and feeding most of the tribe. When the Omaha were ambushed by a band of Sioux, Tibbles acquitted himself well defending the tribe and was inducted into the Soldier Lodge Society, a great honor.

Later, Tibbles married and became a traveling minister with his wife playing hymns on her little melodeon. Eventually, Tibbles got the call to become a newspaper reporter and rose to assistant editor of the Omaha Herald.

After Crook’s men brought Standing Bear to Omaha, the general tracked down Tibbles and burst into his friend’s office at one o’clock in the morning on March 30, 1879. “You have a great daily newspaper here which you can use,” Crook said. “I ask you to go into this fight against those who are robbing these helpless people. The American people, if they knew half the truth, would send every member of the Indian Ring to prison.”

Crook was referring a loose conspiracy of government officials, reservation agents, and others who made a living off cheating the Indians. A few years before, a key member of the Indian Ring, Grant’s Secretary of War William Belknap, had been impeached by Congress for accepting bribes from companies trading on the reservations.

Tibbles and Crook talked in the Herald offices until the first streaks of dawn were appearing in the Eastern sky. Tibbles wrote an essay for the newspaper that day and sent it out to other papers cross the country. It received widespread attention.

A few days later, Standing Bear was brought to a hearing in front of Gen. Crook. “I had found the white way was a good way,” claimed Standing Bear. “I always obeyed every order that was sent me. I never committed a crime in my life. Yet here we are – prisoners.”

The chief pointed out their tribe had signed all the treaties that were forced on them, and broken no law. He didn’t want to remain on the reservation in Oklahoma. Why couldn’t he just be like any ordinary American citizen?

Unfortunately, while the 14th Amendment that had granted rights to former slaves 11 years earlier, did not give citizenship to Indians. It defined the right of any person in the United States to life, liberty, and property unless they were removed by due process of law. But Indians were considered non-citizens even though they had been born on American soil. Since they were not deemed to be “persons” under the law, they could not sue in court or seek redress legally for wrongs against them.

Tibbles and Crook came up with a novel strategy. They would help Standing Bear sue Crook, representing the government, for wrongful imprisonment of the Ponca. They found two attorneys willing to take on this important case on a pro bono basis and filed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Standing Bear in the U.S District Court in Omaha. But would the case be allowed to proceed? Tibbles tracked down the presiding judge, Elmer Dundy, in the wilds on a bear hunt, while back in Omaha Crook anxiously hoping he would be served with the writ before orders from Washington caught up with events in Nebraska.

The hearing began later in April. The lawyers made their arguments, and then Standing Bear asked to be allowed to speak. Since the rules of procedure would not allow this, Judge Dundy quietly murmured that “Court is adjourned,” and then told Standing Bear he might speak. The chief, standing before the packed courtroom in his full regalia, remained silent so long the crowd grew nervous. Finally, he held up his hand and, speaking to the judge, said, “That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be of the same color as yours. I am a man. The same God made us both.”

The chief continued by recounting a dream he had had that included the judge, and soon the courtroom was filled with the sound of sobbing. “I saw tears on Judge Dundy’s face,” Tibbles later wrote. “General Crook sat leaning forward, covering his eyes with his hand.” When Standing Bear finished, the courtroom erupted with “a great shout.” Crook was one of the first to shake the chief’s hand.

A few days later, Dundy issued his ruling that “an Indian is a person” with equal standing to other natural persons and entitled to the rights and protections of the law. It was an extremely important precedent case, and an important moment in the history of civil rights.

Furthermore, the government had failed to show any basis for the arrest of the Poncas. “The right of expatriation is a natural, inherent, inalienable right and extends to the Indian as well as to the more fortunate white race,” wrote Dundy. “Expatriation” meant living the reservation just as immigrants left their countries to come to the U.S.

Standing Bear and his followers were freed. But they still had lost their land and belongings. Tibbles decided to take the chief on a tour across the country to seek support. Standing Bear spoke no English, so the Omaha Chief Iron Eye allowed his daughter Bright Eyes, also known as Susan La Fleche, to travel with them to translate. She had received an education at the mission school and later a private school in New Jersey.

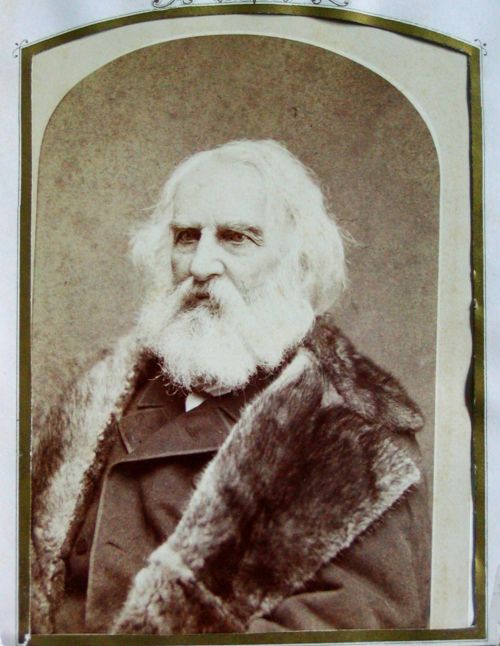

The group traveled east speaking wherever they could, calling called attention to the suffering of those Ponca who were still stranded back on the reservation in Oklahoma, and the plight of Indians on reservations who were often robbed by agents and denied food, clothing and tools that the government had promised. In Boston, they were introduced to crowds and supported by such intellectuals as the abolitionist Wendell Phillips, the orator Edward Everett Hale, and the poet Helen Hunt Jackson (known as HH).

They were entertained by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at his home at Cambridge. When he saw Bright Eyes, he said, "This could be Minnehaha," the Indian maiden in his poem, "The Song of Hiawatha".

Tibbles faced continued hostility and opposition from the Indian Ring. Later he was arrested for setting foot on a reservation, and friends of the Indian Ring vilified him for what was called “lawless agitation.” Secretary of the Interior Schurz himself wrote that “it is difficult to exaggerate the malignant unscrupulousness of the speculator in philanthropy hunting for a sensation.”

Eventually, the Hayes administration allowed Standing Bear and some of the tribe to return to their Niobrara homeland. On March 31, 1881, Congress appropriated $165,000 to indemnify the Poncas for losses resulting from their removal to Indian Territory and sent a delegation to the Sioux to discuss returning some land to the Ponca. Eventually, more than 20,000 acres were restored to them.

Years later, Tibbles reflected on his role in this case: “I cannot recall any … work of my life with which I feel better satisfied,” he wrote.