During the Black Panther trials in New Haven 50 years ago this summer, a remarkable group of leaders helped calm a boisterous crowd of protesters.

-

June 2020

Volume65Issue3

Editor’s Note: In May 1970, my Yale classmate, Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr., and I watched National Guard soldiers roll heavy tear-gas machines across the historic New Haven Green. The compressors emitted a loud hum as they pushed clouds of stinging smoke toward a crowd protesting the trial of Black Panther leader Bobby Seale.

Radicals in the Weather Underground had threatened to set off bombs. We were terrified they would destroy Yale’s post office and phone system, which happened to be directly under my first-floor dorm room. (Later that week two bombs did detonate a half mile across campus at Yale’s Ingalls hockey rink, but no one was hurt.)

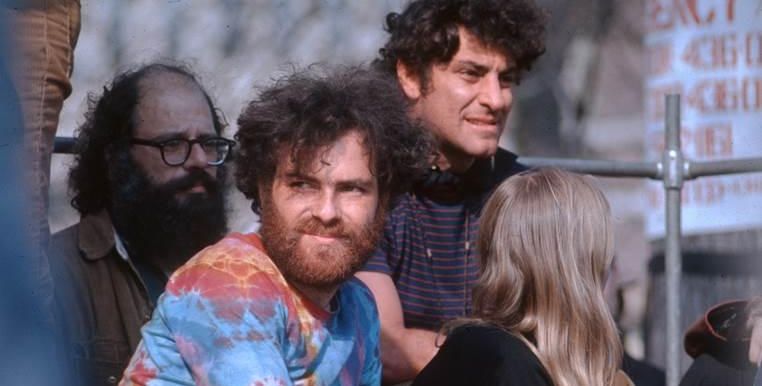

As tear gas billowed across the green and soldiers in battle gear moved toward us, I ran up the street to my dorm, knowing the armband identifying me as a “student marshal” wouldn’t protect from arrest. Hurrying through the gate into Saybrook College, I was shocked to hear low, droning sounds coming from inside the courtyard. Tear gas here, too? But the hum turned out to be not a compressor but the poet Allen Ginsberg repeating an Om mantra into a megaphone to calm students. A few days later in 1970, the relative success of the New Haven protests was overshadowed by the tragic shootings at Kent State.

I’m delighted that Skip agreed to recall for American Heritage those tense days and the successful efforts to defuse what could have been a more unfortunate situation. In recent weeks this year, authorities across the U.S. could have learned from the leaders of 1970 how to listen, empathize, and defuse a protest rather than inflame it.

Skip Gates has had a distinguished career since as historian, literary critic, department chair at Harvard, and now television interviewer and producer of the wonderful PBS series Finding Your Roots. He adapted the following from an essay he wrote as the introduction for the book May Day at Yale, 1970: Recollections: The Trial of Bobby Seale and the Black Panthers by Sam Chauncey, the brilliant Yale administrator who played a key role in the events of those days.

—Edwin S. Grosvenor

By Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

On the eve of May Day, 1970, a nation weary of a war increasingly perceived as immoral and rocked by ongoing racial tensions still raw from the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., awaited Armageddon in perhaps the most unlikely place of all: on the campus of Yale University in downtown New Haven, Connecticut, where I was a sophomore.

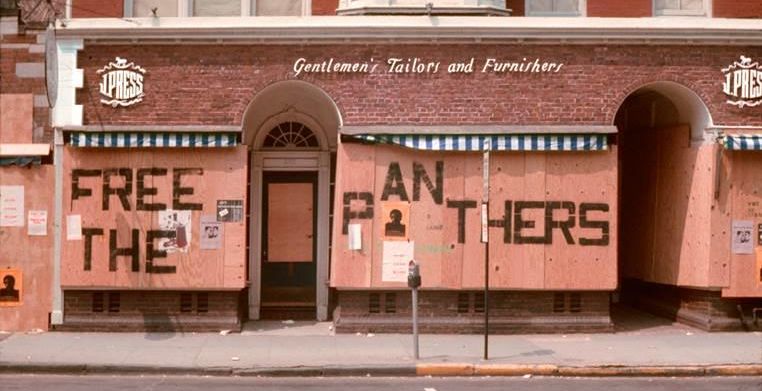

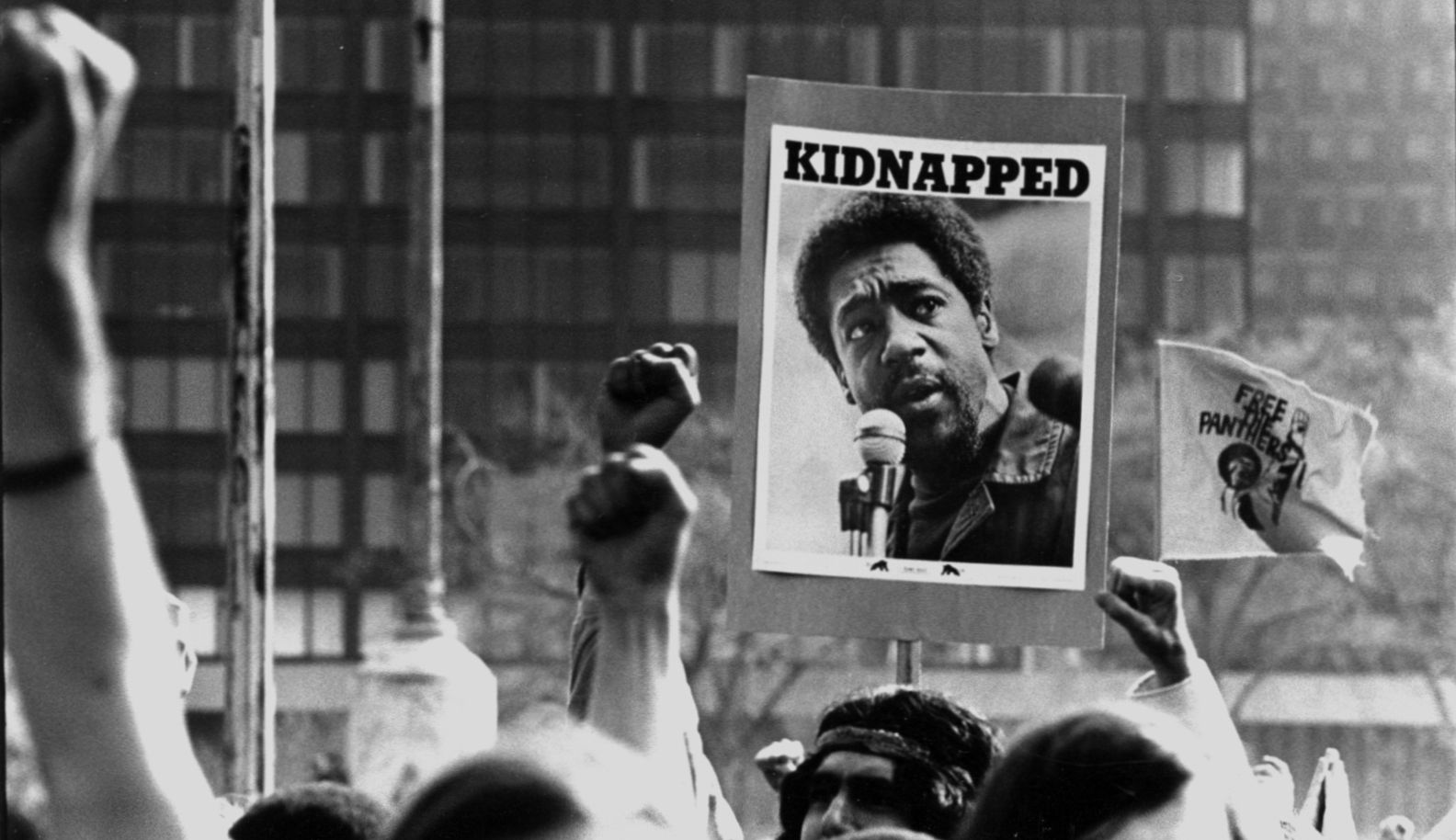

Our expectations were that a mass demonstration of college students, black and left-wing radicals, and perennial “outside agitators” would sweep over the green in protest over the jailing and unfair trial of two Black Panther Party leaders accused of conspiring to murder one of their own.

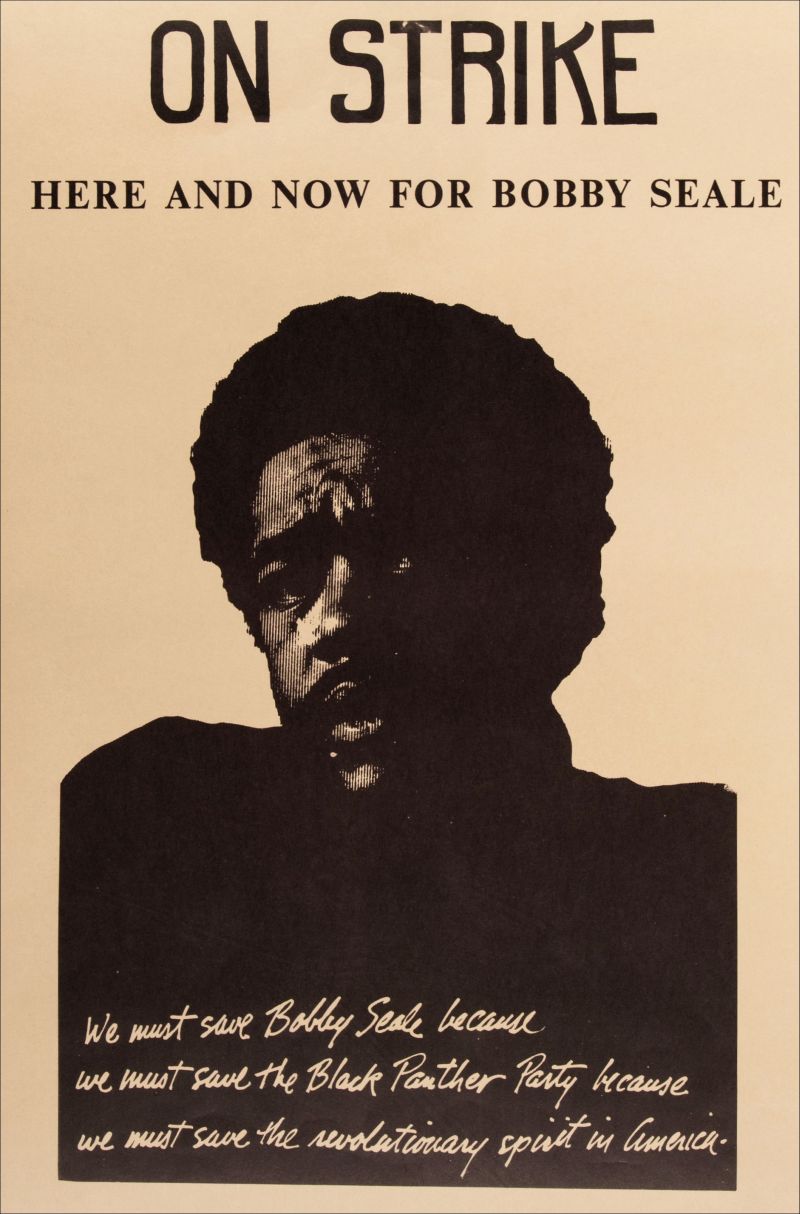

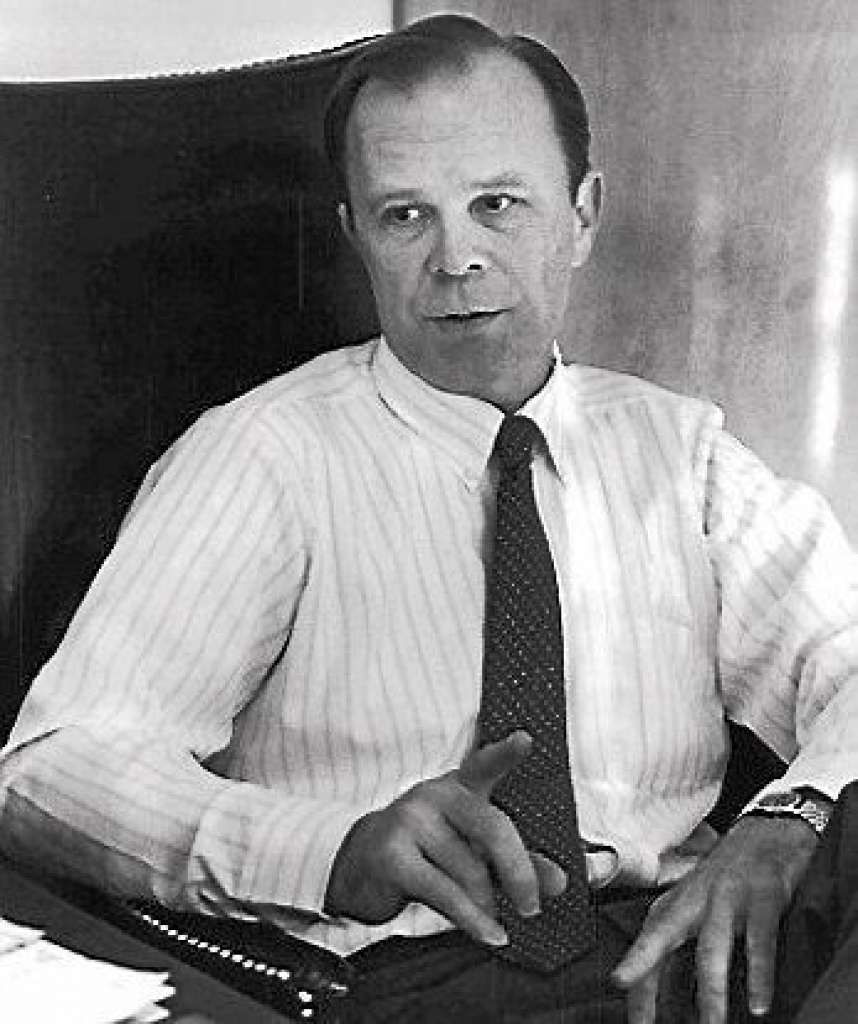

Many thought it was the government that should have been on trial for manipulating the case to break the Panthers’ backs, while a far dirtier operation was underway in Vietnam. That no lives were lost by the following sunset was a miracle. Actually, much of the credit goes to the legendary president of Yale University, Kingman Brewster, and his special assistant, Henry “Sam” Chauncey, and to four black student leaders, Ralph Dawson, Glenn De Chabert, William F. Farley, Jr., and Kurt Schmoke, who answered the “mayday” call for peace that 1st of May, and in doing so, helped defuse what easily could have been “Kent State” before the real tragedy of the murder of protesting students at the Ohio campus devastated the country three days later.

The facts are expertly reported in Paul Bass and Douglas W. Rae’s definitive book, Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, and the Redemption of a Killer (Basic Books, 2006). The murder of the 19-year-old Black Panther Alex Rackley in New Haven on May 20, 1969, resulted in the arrests of two Black Panther leaders, Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale (in addition to the killers, also Panthers), as part of the federal government’s determination to crack down on the party’s growing media presence and popularity.

By the following spring of 1970, the remaining Panther leadership set their sights on New Haven as the new ground zero in their war against “the system,” capitalism, and “white oppression.” Monitoring the situation at Yale was President Brewster and, in Washington, President Richard Nixon and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, neither of the latter exactly on cozy terms with Black America.

The escalation began on April 14, 1970, when black area high school students, rebuffed at the local courthouse, took their frustrations out on the Chapel Square Mall. The next day’s reaction witnessed further violence at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when the administration there locked its gates on 1,500 protesters massing in the streets with nowhere to go but the hospital. In response, the Youth International Party (Yippie) leader Abbie Hoffman announced that the movement’s next step would be Mother Yale, as we affectionately nicknamed our beloved institution.

To head off Hoffman, President Brewster, in a stunningly clever move, characteristic of the tenor of his presidency, conferred privately with Harvard point man, the law professor Archibald Cox (of future Watergate fame), who warned Brewster not to make the same mistake Harvard had made in locking down the campus.

The fabled Harvard-Yale rivalry aside, this was a classic example of two brilliant men, both broadly liberal in their sensibilities and both national leaders, seeking to avert another campus disaster, one that would have enormously harmful ramifications throughout the academy, spilling over into the larger society outside, especially since both institutions had only recently begun to implement affirmative action admission policies that had led to the admission of the largest number of black students in the freshman class at either institution.

As May Day approached, Black Panther organizer Doug Miranda exhorted Yale students to burn their campus down in protest of Bobby Seale’s capture: “You ought to get some guns, and go and get Chairman Bobby out of jail.” His hope was to spark a more protracted strike, even if that meant risking the lives of my fellow Yalies.

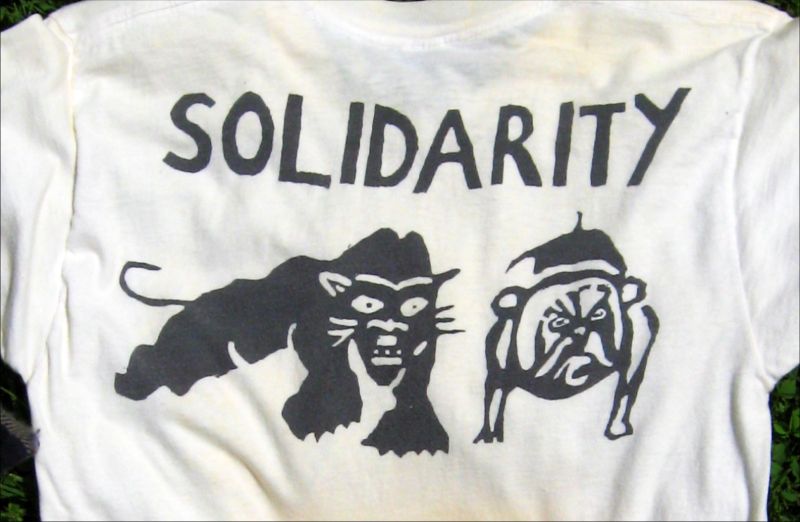

“That Panther and that Bulldog gonna move together!” Miranda shouted to thunderous applause at Batten Chapel on April 19 — the anniversary of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, for what it’s worth.

Soon, t-shirts with the two animals, one black, the other white and blue, peppered the campus. Stepping forward to lead the student committee was my friend, Bill Farley, who would be selected as a Rhodes scholar in his senior year (Class of 1972). Farley, along with Ralph Dawson (Class of 1971), moderator of the Black Student Alliance at Yale (BSAY), Glenn De Chabert (Class of 1970), and Kurt Schmoke (Class of 1971), who would be chosen as a Rhodes scholar the year before Farley and would go on to be elected the first African American mayor of Baltimore in 1987, made the critical decision to open a back channel to President Brewster, even as Farley publicly warned of his plans to help shut Yale down.

I remember when that decision was made: De Chabert, during an emergency meeting of the BSAY, said that he had come to the realization that the Panthers actually wanted to “heighten the contradictions,” as the left-wing saying went, by showing the country that even white, privileged Yalies could be victims of the police brutality sure to ensue in the chaotic aftermath of the May Day rally. The BSAY would cooperate with Kingman, he said, to keep that from happening,

All of a sudden, it was the Panthers who had to be controlled. Supported, yes, but also their activities and influence controlled. And that was going to take some deft footwork. We became so alarmed, and frankly frightened, by the escalating threats that we attempted to force the black female members of BSAY to seek protection during the rally within the formidable walls of the Scroll and Key secret society, much against their wishes.

Brewster, Dawson, De Chabert, Farley, and Schmoke were natural allies: each a strong leader, each charismatic, each as strongly attached to his ethnic identity as he was attached to Yale: Black and Blue. And while my four friends and fellow black students were, to a person, left of center and cultural nationalists, they never, even once, considered violence or anarchy a viable option for the black community, especially the black community at Yale.

“Black and Blue” was our generation’s motto. And these three guys wanted to lead America, not destroy it. What’s more, nobody in their right mind wanted to see anyone killed in the process of protesting the miscarriage of justice that was occurring in the New Haven courthouse, or the Vietnam War.

Only mad or desperate women or men embraced that option, and Dawson, Farley, De Chabert, and Schmoke were anything but mad: each had come to Yale to transform the system from within, not to tear it down. And each found in Kingman Brewster — most famous before the strike, I think, for his annual speech to the freshmen welcoming them to New Haven as this year’s cohort of Yale’s “One Thousand Male Leaders” — a model of how the power elite, at least as Brewster defined and embodied it, was dedicated to integrating the American power structure and simultaneously perpetuating the ruling class by diversifying it with “natural aristocrats,” as the saying went. And if ever this curious phrase applied to four born leaders, it was to Dawson, De Chabert, Farley, and Schmoke.

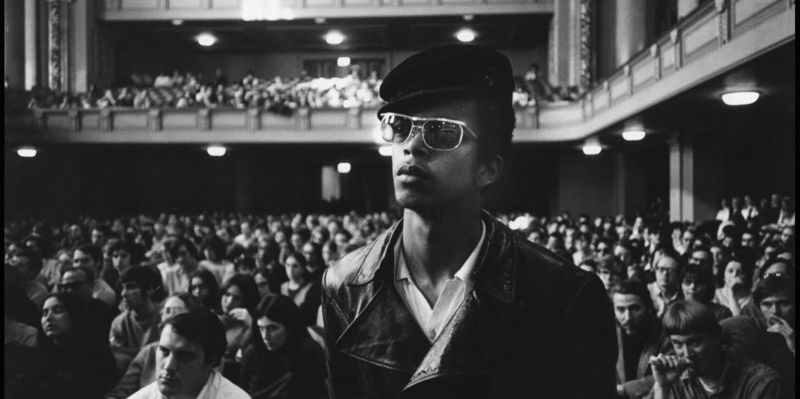

April ended with the worst boiling over: at a mass meeting on the 21st before a standing-room-only crowd at Yale’s Ingalls Rink, Black Panther David Hilliard (just that day freed from jail) was boldly challenging the crowd of thousands of our fellow students to “off the pigs” when an architecture student, deranged enough to jump on the podium in the middle of Hilliard’s speech, was beaten by Hilliard’s security, much to the horror of all of us in the audience.

Suddenly, “the Revolution” was no longer just a phrase: human beings like us were as vulnerable to violence as any inner-city resident being victimized by the police. “Fuck you! All power to all those except those who want to act like a bunch of goddamn racists,” Hilliard exclaimed, as he coaxed the crowd to recover from the stomping of that student, who ultimately was allowed to speak. We couldn’t tell if this guy’s incoherent mumblings were a sign that he had been unbalanced before he jumped on the platform, or of how badly he had been beaten by Hilliard’s bodyguards. But the effect of that beating was terrifying, and I think it contributed considerably to our determination to protect this university of which we found ourselves a vital part and which, we realized, we had come to love.

With his options vanishing, President Brewster heeded Archibald Cox’s advice: after making a show of defiance, he “relented” by agreeing to keep Yale’s gates open on May Day. You might call it Brewster’s safety-valve plan. It included his decision to announce at the next Yale faculty meeting on the 23rd that academic “expectations” would be eased to avoid ruining students distracted by what was about to unfold. Immediately, some of the “Old Blues,” as we call our alumni, charged him with selling out. But Brewster was determined not to have any blood on his hands. More startling, perhaps, was the immortal prophecy he shared: “In spite of my insistence on the limits of my official capacity, I personally want to say that I am appalled and ashamed that things should have come to such a pass in this country that I am skeptical of the ability of black revolutionaries to achieve a fair trial anywhere in the United States.” Brewster’s honesty endeared him to us, but it would prove costly to his career.

Horrified by what he was hearing, U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew opined critically, “I do not feel that students of Yale University can get a fair impression of their country under the tutelage of Kingman Brewster” — exacerbating the right wing’s paranoia that the nation’s elite universities were a hotbed of liberalism and anarchy and affirmative action.

More than a thousand alumni letters streamed in following Brewster’s announcement, most of them supportive of his leadership, but many calling for his head.

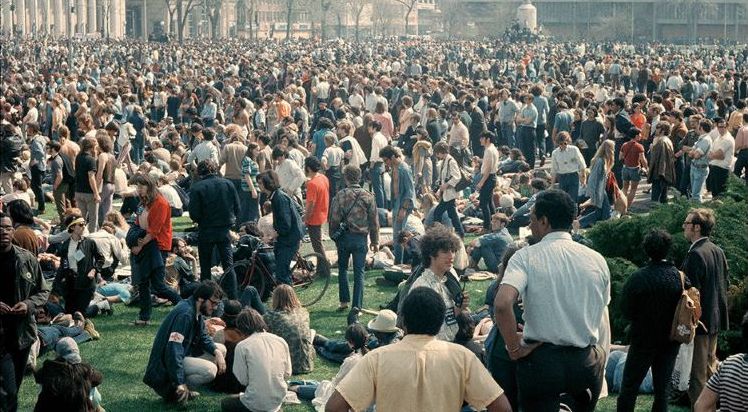

In the final days counting down to May 1, four thousand National Guardsmen were ordered to New Haven to join local police in halting what we felt was the inevitable Armageddon, with reports swirling of stolen arms and explosives reinforcing powder-keg impressions and damaging town-gown relations at Yale. Breaking from the radicals about to run over the campus, the moderate Black Coalition in the area expressed the view that “in New Haven, as in most of the country ... the white radical, by frantically and selfishly seeking his personal psychological release, is sharing in the total white conspiracy of denial against the black people.”

The final match was lit by then-National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and President Nixon himself, when on April 30, the eve of May Day, Nixon took to the airwaves to announce an assault on Cambodia to a nation already exhausted from waiting for peace to arrive in Vietnam. This only sent further shockwaves across campus, with hundreds of reporters descending on New Haven to tally the horrors about to unfold. On both offense and defense, President Brewster, working closely with his black student allies in secret meetings at his house, did his best to keep the police and protesters far apart.

When May Day finally arrived, tanks were at the ready in the streets, while the Yale flagpole had been greased to avoid any violently unpatriotic displays. If they couldn’t reach the flag, they couldn’t burn it. Prepping the protesters that morning, Yippie leader Jerry Rubin railed, “Fuck Kingston Brewster!,” misspeaking the name for posterity and alienating the Panthers with his ridiculously immature declaration, “The most oppressed people in America are white middle-class youth. . . . We don’t want to work in our daddy’s business. We don’t want to be a college professor, a prosecutor, or a judge. . . . We ain’t never, never, never gonna grow up.”

The “Big Rally” kicked off at high noon, with what seemed to us like 100,000 protesters gathering on the green. (The official number was around 15,000.) Rock music blared. Whispers of a Weathermen presence filtered out, never to be confirmed. Mostly, though, a horde of speakers droned on into late afternoon and evening, before it was time for Allen Ginsberg to chant his poem, which included the line, “0 holy Yale Panther Pacifist Conscious populace awake alert sensitive tender.”

For the time being, it appeared that was going to be it. But then, at 9:30 p.m., the action shifted back to the green, after a report surfaced on the Yale campus that police were arresting black men upon entering. Later known to be untrue, that report was all it took to rile up the crowd. After a half hour, the marchers, 1,000 strong, headed to the courthouse side of the green, where they eventually collided with police teargas. A regrouping effort a few blocks away was further frustrated when a letter from “Chairman Bobby,” Seale himself, was read, warning the protesters not to damage the Panther cause.

At that point, panic and paranoia set in, with misfired reports about Yale’s gates being closed. Then, when that was about done, a pair of bombs suddenly went off in the Ingalls Rink basement, damaging the structure, but, thankfully, not taking a single human life. No one knew anything for certain in the minutes and hours that followed, except that the hourglass on May Day had just about run out. I remember running through Old Campus, nose covered with a handkerchief to avoid the cloud of teargas and marijuana, as Ginsberg chanted still another mystical-political poem. So this was “the Revolution,” I thought to myself.

It could have been worse, far worse. As it turned out, there were no major injuries suffered, and only twenty-one total arrests were made. While the next day saw some attempts to spark another round of protests, mostly they just fizzled. Kent State was just two days away now, followed by the murder of two students at Jackson State on the 15th.

The shocking violence at those two campuses would live on in national memory forever, while the events of May Day at Yale receded, except for those of us who had been there and remembered what it felt like to stand on the precipice of Armageddon, and who live to remember that noble day when the privileged students at Yale took a stand against the unlawful persecution of the members of a radical black political organization because of their revolutionary beliefs.

“Call it luck. Call it brilliant planning. Call it a conspiracy between the Man and the Panther. Whatever the reason, death and destruction passed by New Haven,” Paul Bass and Doug Rae conclude in their book, Murder in the Model City (to which I’m indebted for helping me recall the tick-tock of those intense days and months).

For many of us who witnessed this exciting time, it was the most noble moment in the history of Mother Yale.