-

December 1996

Volume47Issue8

He was dead at the age of fifty-four, an extraordinarily talented man who probably could have made $100,000 in a good week as a well-connected Washington lawyer. But in a society where the first questions are usually about what you do and how much you’re paid for it, Brown was risking life and limb on another American fool’s mission. Like millions of his countrymen before him, he was trying to make the world a better place for people he did not know and probably misunderstood. For this he was being paid $99,500 a year.

He was praised and honored, posthumously. But on the day before he died he was being widely scorned as some kind of lowlife, a status bestowed on him twice over—as “a bureaucrat” and before that as “a politician,” the chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

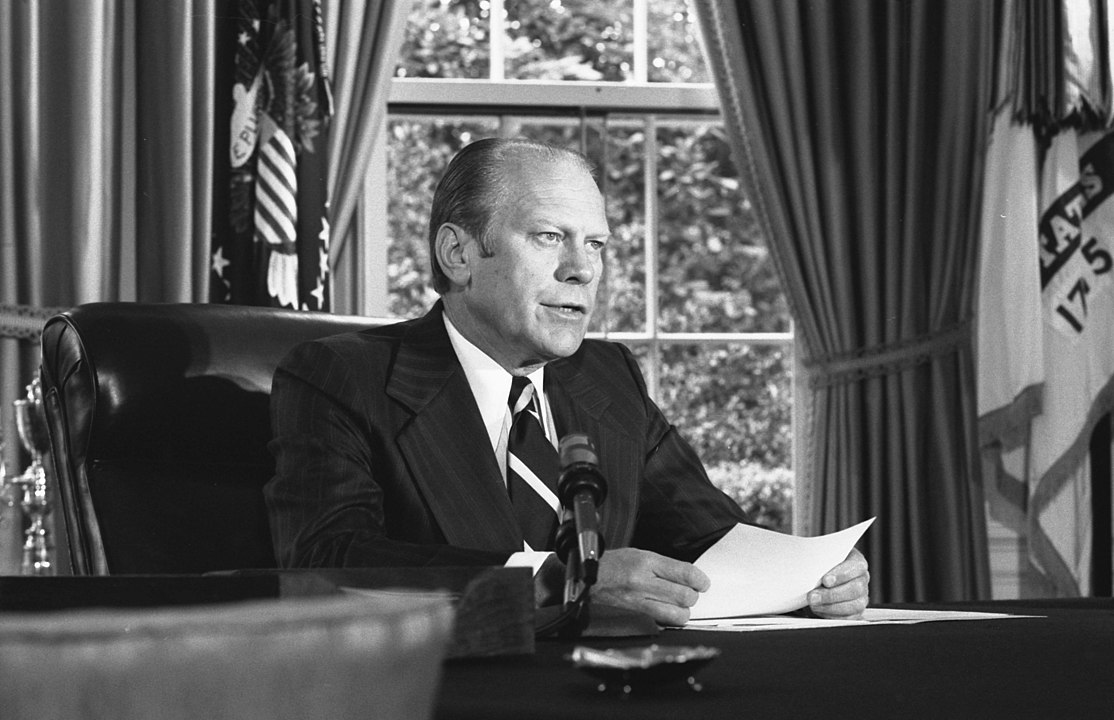

I, of course, am part of the problem. I have found myself thinking more and more about the trashing of American politicians. Most particularly I have thought about a book I wrote twenty-one years ago called A Ford, Not a Lincoln, about the thirty-eighth President of the United States, Gerald Ford. So it was no accident that on a late-night television show when the host, Tom Snyder, quoted something funny he remembered from that work, I mumbled, in passing, “I was too tough on him in that book.”

Maybe I figured no one was watching or listening at that hour. But the editor of this magazine, Richard Snow, wrote to me the next day and said someone on his staff had heard what I said. Exactly what did I mean?

I meant, in general, that Jerry Ford, perhaps the most accidental of American Presidents, had done a better job than I had predicted or imagined. I know better now than I did then that Presidents should be judged on the one, two, or five big things they do. The day-today politics and stumbling fade in memory, as it should, though poor Jerry Ford has had to live with endless reruns of the comedian Chevy Chase imitating his clumsiness week after week on “Saturday Night Live!”

Presidents are not paid by the hour. The job is essentially to react, and we pay them for their judgment— a word Ford routinely mispronounced as “judge-ament.” In retrospect Ford’s judgment turned out to be better than his pronunciation. His big job, as defined in a transition plan written by a group of young Nixon staffers working without the knowledge or permission of either Nixon or Ford, was simply: “Restoration of the confidence and trust of the American people in their political leadership, institution and processes.”

On balance he did that, producing more trust than confidence—or at least he checked or slowed the slide toward today’s foul public cynicism. To do so, Ford decided he had to pardon Nixon. I thought that was wrong then, and so did most Americans. I also had no doubt, as I documented to my satisfaction in the book, nor do I have doubt now, that the pardon was part of a deal, spoken or unspoken, brokered by Nixon’s chief of staff, Alexander Haig.

More specifically, I mean that Ford understood (or guessed at, it doesn’t matter which) something that I now realize was true. He told me something in 1974, or not too much later, that I can only paraphrase because I did not take it seriously enough: that it would have been impossible to govern the country if there had been open charges against Nixon, that the television-focused attention of the nation would have followed the disgraced President from courtroom to courtroom.

He was right. Whatever his failings as a leader, and they were many, he was right about the big one. We have turned out to be a television nation that has trouble focusing on anything else for months when we can watch a stone-faced old football player accused of murdering his wife.

As the years passed, I concluded that Ford’s pardon and the dissembling in which it was packaged for public consumption were not so different from a critical (and fundamentally cynical) decision by a leader of true greatness, Charles de Gaulle. It was de Gaulle, in 1944, who had to decide how France would purge the collaboration that had been common during the German occupation that began in 1940. Well, to simplify the story, the new leader of France executed Pierre Laval, the collaborationist prime minister, exiled Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, the aged hero turned Nazi puppet, and threw some other notable collaboratetors in jail. C’est tout . He thus created and sanctified a national myth that everyone else had served in the resistance.

Vive la France! He did what he had to do, and if he hadn’t, the French would still be chasing one another through village streets over things that happened more than fifty years ago. Ford did what he had to do too. “Close the book on Watergate” were the words he used in a taped television announcement on September 8, 1974, a Sunday, his thirtieth day as President. He was playing golf when the television networks ran the tape. He took a tremendous political hit. Not only did his approval ratings drop, but he lost the 1976 election because of his actions and words on that day.

He also ended, almost violently, a thirty-day honeymoon with the press. Mel Elfin, the Washington bureau chief of Newsweek , later said: “I stood on my balcony and watched that chopper taking Nixon away after he resigned, and it was like I was coming out of Buchenwald. In that mood even a thirty-five-cent hamburger tastes like steak.”

We had suddenly dared to trust—and felt betrayed again. Ford’s press secretary, Jerald terHorst, who had been a columnist for the Detroit News , quit when the pardon was announced. A newspaperman for more than twenty-five years and a press secretary for only thirty days, terHorst could not break the habits of a lifetime. None of us could, and one consequence was a lost opportunity to break a long and continuing cycle of press-politician hostility.

Ford had the guts to take the hit. I, for one, did not have the sense to calm down and get beyond the obvious and into what he might have been thinking. That was part of what was on my mind as I talked with Tom Snyder twenty-one years later.

I do not mean to say that President Ford was an innocent. When he was confirmed by Congress as Vice President, in December 1973—replacing Spiro Agnew, who had turned out to be a crook—he was asked about a pardon for Nixon and answered, “I do not think the public would stand for it.” He reiterated that sentiment, through the White House press office, on his first day as President, August 9, 1974.

I have been troubled not only by my shortsightedness but also by the impact of my own reportage in those days, its impact not on one President but on political journalism or the political dialogue of the country. I don’t want to exaggerate. A Ford, Not a Lincoln was no world-changing book. It was well reviewed and hung around the middle of bestseller lists for a few weeks, especially in Washington. Actually, my memory of impact relates more to a New York magazine article that included part of the book. The cover was a faked photo of Bozo the Clown in the Oval Office; the headline was LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES .

I also remember something very important about the book’s promotion tour in the fall of 1975. I did a lot of radio call-in shows around the country, which were mostly late-night affairs in those days. I was stunned by the hatred of Washington I heard and by repeated conspiracy theories I considered wacko. It was nothing compared with what goes on around the clock and around the dial today, but coming back home then, I thought and wrote that Ford was probably finished because he was seen as a Washington candidate. I said then that the men to watch were the anti-Washington candidates, Jimmy Carter of Georgia and Ronald Reagan of California.

Frightening was a word that had appeared again in the reviews of A Ford, Not a Lincoln. Newsweek said: “Frightening and provocative in its demystification of a President.” In England the Sunday Express said, “A totally amusing and frightening read.” The Times of London added: “Not the kind of book you could imagine a British political correspondent writing about Harold Wilson.”

Those words have a different meaning to me now than they did then. Were they and the book part of the buildup to acid-in-your-face “character” politics?

The new savagery peaked for me one fine day in August 1994 as I walked out of the Capitol of the United States. There was a gleaming black bus with a Star Wars look parked on Independence Avenue. Painted along the side of it was the legend “Impeach Clinton Tour ’94.” Below that line ran this list of real or feverishly imagined presidential transgressions: “Womanizing…Troopergate…Deception…Abortion…Adultery…Bribery…Sodomy…Fraud… ADFA…Abuse of U.S. Constitution…Obstruction of Justice…Document-Shredding…Drug Abuse…Tax Evasion…Gennifer Flowers…Paula Jones.”

Some list. At the same time I saw advertisements for a $19.95 video, produced quite professionally in California and promoted by Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority, that explicitly accuses President Clinton and his wife of bigtime drug dealing and murder.

So it had come to that. Was I responsible?

Yes, partly.

I reread the Ford book written by a young man using my name. It was the first time I had ever done that with any of my books. It was pretty good, perceptive and better written than I had expected, if I do say so myself. Witty. “Sprightly” was a word William F. Buckley had used in the New York Times review. It was not wrong or stupid. It offered a coherent explanation of why politics and Washington were the way they were—and still are, only more so.

But it was also cruel, unnecessarily so. As a national leader President Ford was a man with many flaws and more inadequacies. But he had become President by accident, done the best he knew how, and, we now know, muddled through a very dangerous time.

This was my rationale in the introduction: “Jerry Ford is a pretty nice guy and a professional politician. This book is about the latter.… I do have a bias about politicians. I don’t feel any great obligation to recount their many and varied personal and professional virtues. That is what they, or the taxpayers, are paying for in salaries and fees of press secretaries, media advisers and advertising agencies. Believe me, there is nothing good about Jerry Ford, Nelson Rockefeller, or any of the Kennedys that the American people have not been told—these politicians and all the others have staffs that make sure we know they love their country, wives, children, dogs and fellow man.”

I could go on—and I did, back then. Today politicians and their media consultants say worse things about one another than I ever did, not realizing or not caring that the public does not keep careful score of charge and countercharge. If the candidates all call one another knaves and fools, we take their word for it and judge them all to be bums.

So they, and we, continue to poison the wells of democratic faith and our political dialogue. I wish I had not been part of the problem, and perhaps I will find a way to be part of the solution. I’ll begin by saying to Gerald Ford that I know he did his best and did what he thought he had to do: You have my respect and thanks, Mr. President.