In his second term, George Washington faced a crisis that threatened to tear apart the young Republic. His wife Martha later thought the bitterness of the debate may have hastened the President’s death, but Washington gave America the gift of peace, and an important precedent in leadership.

-

Fall 2017

Volume62Issue5

In August 1795, at Mount Vernon, as the rains pelted his red shingle roof, spinning the dove-of-peace weathervane, George Washington bent over his candlelit desk, dipped a quill in black ink and tensely scratched out letter after letter. He was feeling “serious anxiety” in a time of “trouble and perplexities.”

For twenty years, since the start of the Revolution, he had taken as his due the bands playing “The Hero Comes!” and the lightstruck Americans cheering “the man who unites all hearts,” but now the national adoration for Washington was fading. Americans had learned that a secret treaty negotiated by his envoy John Jay made demands that many found humiliating. One member of Congress said the fury against “that damned treaty” was moving “like an electric velocity to every state in the Union.”

As the public tempest had swelled, some wanted Washington impeached. Cartoons showed the President being marched to a guillotine. Even in the President’s beloved Virginia, Revolutionary veterans raised glasses and cried, “A speedy Death to General Washington!” Reeling from the blows, the sixty-three-year-old Washington wrote that the “infamous scribblers” were calling him “a common pickpocket” in “such exaggerated and indecent terms as could scarcely be applied to a Nero.”

In the spring of 1794, the British were arming Indians and spurring them to attack Americans trying to settle the new frontier lands that would one day include Ohio and Michigan. London was reneging on its pledge, made in the peace treaty ending the Revolutionary War, to vacate royal forts in the trans-Appalachian West—Oswego, Niagara, Detroit, Michilimackinac.

Because Britain was at war with France, British captains seized U.S. ships trading with the French West Indies. Renouncing the agreed-upon border between the U.S. and Canada, Britain’s governor in Quebec predicted a new Anglo-American war “within a year.” Former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who hated England and adored France, demanded retaliation against the British. But Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton warned the President not to plunge into a war that America could not win.

Hamilton urged him to send an “envoy extraordinary” to London. A new Anglo-American treaty could secure U.S. trade on the Atlantic and the Great Lakes, giving their country time to build its economy and defenses and settle its frontier. Then if America one day had to fight off Britain, it would be far better prepared.

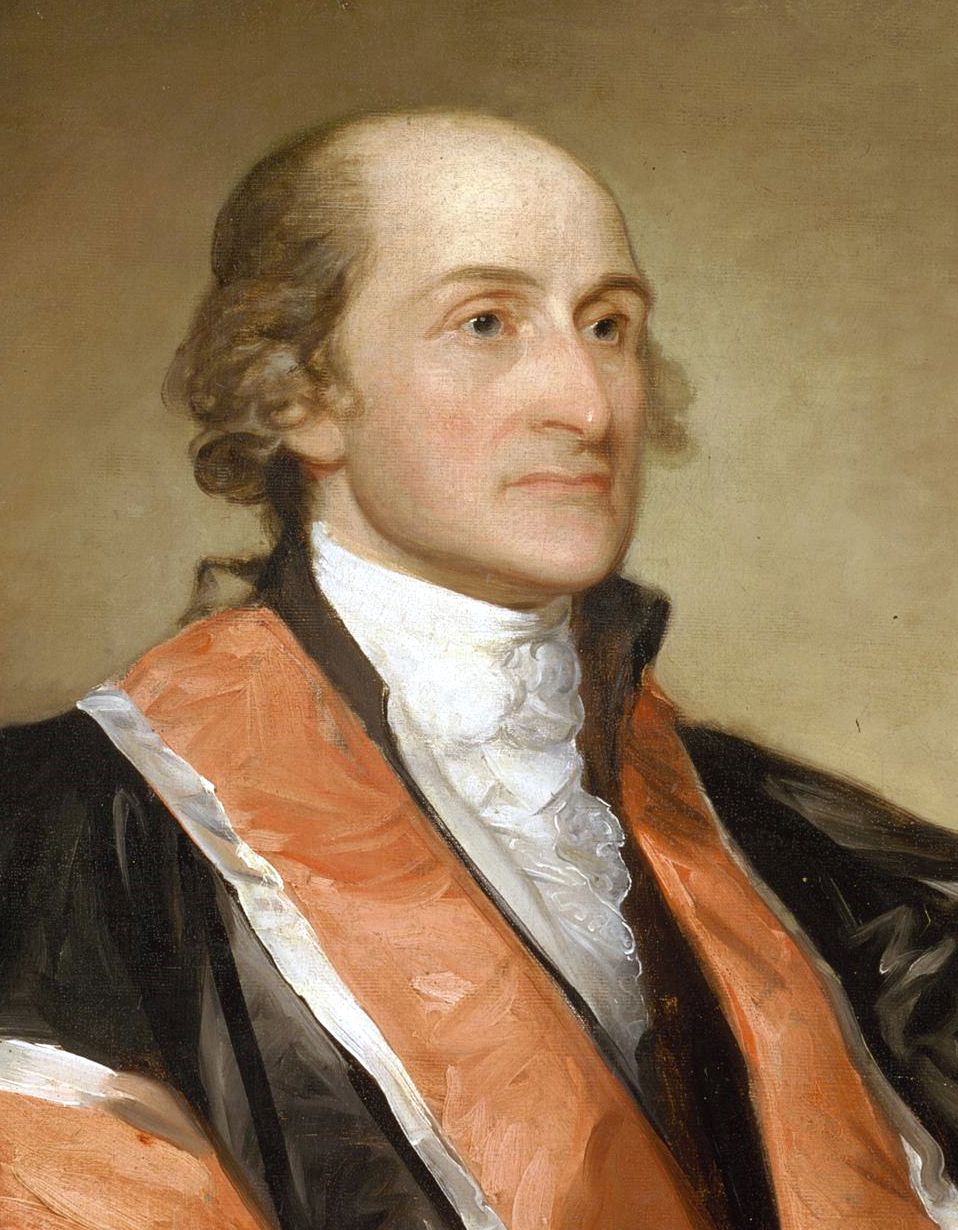

Washington agreed, but he knew that appointing Hamilton envoy would inflame the Jeffersonians. Instead, at Hamilton’s suggestion, he chose the aristocratic Chief Justice, John Jay of New York.

Soon after Jay’s departure in May 1794, the British reclaimed and fortified one of their old posts on American territory near Detroit. Having jeopardized his prestige to talk with Britain, Washington was furious. He wrote Jay that it was “the most open and daring act of British agents in America.” He noted that some wished him to turn the other cheek: “I answer NO! ... It will be impossible to keep this country in a state of amity with G. Britain long if the Posts are not surrendered.”

Jay got the British to forgo such aggravations while they bargained. He assured Washington that Britain felt it was having a “family quarrel” with America, “and that it is Time it should be made up.” He reported that, excepting the King, the British respected no one more than George Washington, had taken Jay’s presence in London “as a strong Proof of your Desire to preserve Peace.”

In the spring of 1795, Washington received copies of the treaty at the President’s House at 190 High Street in Philadelphia. Upstairs at his mansion, Washington frowned at Jay’s “Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation.” He knew that if he approved it, Americans would excoriate him for truckling to their old oppressor across the sea. Most inflammatory was Article Twelve: America could trade with the West Indies, but not with large vessels. Nor could the U.S. export any products natural to those islands.

Jay’s deal would also cosset the lucrative British fur trade in the American Northwest. The U.S. would pledge never to seize British assets in America, surrendering an important potential weapon for America’s defense. The treaty would also allow the British to keep on halting U.S. exports to France - and to escape paying reparations for American slaves they had carried off during the Revolutionary War.

To keep public indignation from building against the treaty before he sent it to the Senate, Washington ordered Secretary of State Edmund Randolph to keep its contents “rigidly” secret “from every person on earth” - even the rest of his Cabinet. Unlike his successors,

Washington took literally the Constitution’s demand that a President ask the Senate’s “advice and consent” on treaties. He would not finally decide whether to approve Jay’s Treaty until the Senate voted.

On Monday morning, June 8, 1795, two dozen U.S. Senators in powdered wigs and ruffled shirts sat down in Philadelphia’s Congress Hall for a special closed-door session on Jay’s Treaty. During two weeks of debate, Republican Aaron Burr of New York tried to pit Southern Senators against Jay’s Treaty by demanding that Britain pay up for the “Negroes and other property” it had stolen—mainly from the American South. But Southerners were far more aggrieved by Article Twelve’s threat to their exports. Alexander Hamilton, by now a private citizen in New York City, advised Washington to scrap the article in order to save the treaty in the Senate.

The President did so, and by a bare two-thirds vote along party lines, the Senate sent Jay’s Treaty to the President’s House for Washington to sign.

To Washington’s exasperation, the treaty’s contents were no longer secret. A Virginia Republican Senator who reviled it passed a copy to the French minister in Philadelphia, who gave it to Benjamin Franklin Bache, a Francophile and anti-Washington grandson of the famous founder and publisher of The Aurora in Philadelphia.

Bache published the entire text in a pamphlet, which he sold up and down the Eastern Seaboard for twenty-five cents. Flamboyantly, The Aurora ripped the veil off what it called Jay’s “illegitimately begotten” treaty, that “imp of darkness” approved by a “secret lodge” of Senators.

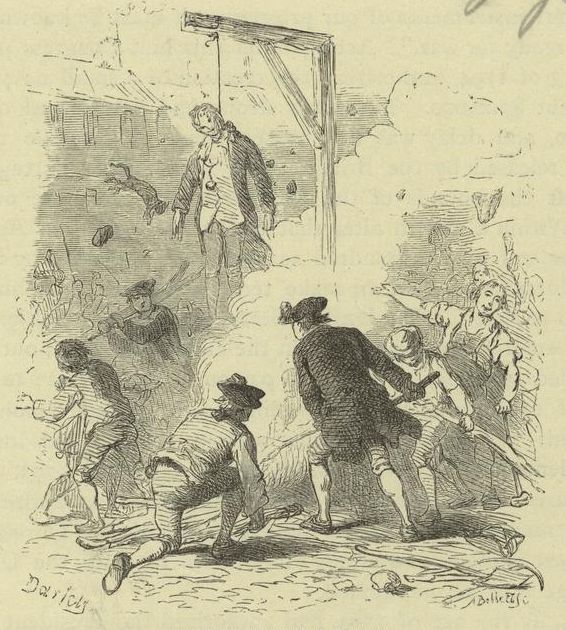

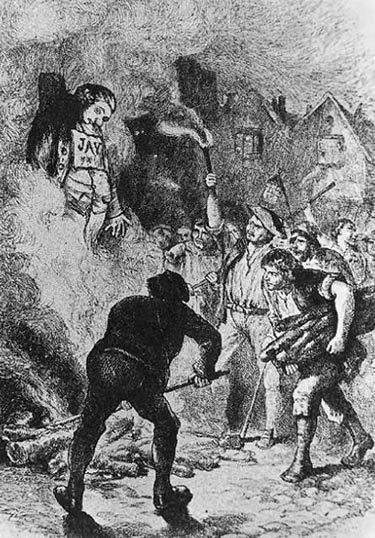

Fulminating that Jay’s Treaty had “made its public entry into the Gazettes,” Washington knew that Bache’s attacks were just the start of a national onslaught. At midnight of Independence Day 1795, a Philadelphia throng burned a copy of the treaty and an effigy of John Jay. Crowds in other cities followed suit. Jay mordantly joked that soon he could walk through all of the fifteen United States by night, illuminated only by the glow of all of his effigies burning.

Girding himself for battle from his home seat of Monticello, Thomas Jefferson found Jay’s Treaty an “execrable ... infamous act” by the “Anglomen of this country.” He warned, “Acquiescence under insult is not the way to escape war.”

With steam rising from Philadelphia’s gravel streets, Washington pondered whether to sign the treaty. From New York, Hamilton wrote the President that his decision should be “simple and plain.” Except for Article Twelve, Jay’s pact was “in no way inconsistent with national honor” and would avert a ruinous war.

Then in early July came a new British insult—a “Provision Order” that U.S. grain ships sailing toward France would be stopped, their cargo confiscated. Secretary of State Edmund Randolph advised the President not to sign the treaty until Britain canceled the Provision Order. Washington asked him to so inform the British minister, George Hammond.

When Hamilton defended Jay’s Treaty in front of New York’s City Hall, people threw rocks, leaving his face bloody. Someone joked that the crowd had “tried to knock out Hamilton’s brains to reduce him to equality with themselves.”

In Boston Harbor, mobs set a British ship aflame. In Philadelphia, they cried, “Kick this damned treaty to hell!” Spearing a copy of Jay’s pact with a sharp pole, the revelers marched it to Minister Hammond’s house, burned it on his doorstep and broke his windows, with Hammond and his family cowering inside.

The new Treasury Secretary, Oliver Wolcott, feared the demonstrations might signal the British that Americans sought war. He wrote his mentor Hamilton, “The country rising into flame, their Minister’s house insulted by a Mob - their flag dragged through the Streets ... & burnt.... Can they believe that we desire peace?”

As the man who had sent Jay to London, the President knew that he could be immolated by the firestorm.

By mid-July 1795, Washington escaped the “suffocating” Philadelphia summer and traveled to his Virginia “Home House.” Soon the fracas over Jay’s Treaty thundered into Washington’s Mount Vernon paradise.

Retiring to his study, he donned spectacles and read the fevered reports from Philadelphia. “The cry against the Treaty is like that against a mad dog,” he recorded. People were “running it down” with “the most abominable misrepresentations,” and “working like bees to distill their poison,” fighting for “victory more than truth.”

The President had yet to make up his mind about Jay’s Treaty. He wrote Randolph that his current feeling was still “what it was: namely, not favorable to it.” But, he went on, if Britain canceled its Provision Order and the “obnoxious” Article Twelve, it was probably “better to ratify it than to suffer matters to remain as they are, unsettled.”

After a week at Mount Vernon, Washington was so agitated by the political storm beyond his gates that he decided to return to Philadelphia. With the country in “violent paroxysm,” he wrote that “a crisis is approaching,” threatening “anarchy,” if not “arrested.” With George Hammond sailing back to London in mid-August, the President felt he had to give the British his verdict on the treaty.

As the President’s bags were packed, he received a baffling, ominous letter (“for your eye alone”) from his Secretary of War, Timothy Pickering. “Return with all convenient speed,” it begged. “On the subject of the treaty I confess I feel extreme solicitude; and for a special reason which can be communicated to you only in person.” Until then, “I pray you to decide on no important political measure.”

Washington left Mount Vernon at the first moment the rains lifted. Reaching Philadelphia on Tuesday afternoon, August 11, 1795, he invited Randolph to his residence for dinner. He also summoned Pickering, who noted that Randolph looked “cheerful” dining with the President.

Taking a glass of wine, Washington rose from the table and winked at Pickering. Leaving Randolph behind, he led the Secretary of War into another chamber and shut the door. Referring to Pickering’s strange message, he asked, “What is the cause of your writing me such a letter?”

Pointing at the closed door, Pickering replied, “That man in the other room is a traitor!”

As Washington’s second Secretary of State, Edmund Randolph was no Thomas Jefferson. He had always liked Randolph, but knew he was ultimately a trimmer and errand boy. Son of a royal Attorney General of Virginia, scion of one of the commonwealth’s most respected dynasties, Randolph had used family connections—including Thomas Jefferson, his third cousin—to join General Washington’s Revolutionary staff, drafting letters and documents. After independence, Randolph took his father’s old place as Virginia’s Attorney General, serving also as Washington’s personal lawyer. By 1787, Randolph was Governor of Virginia, and by 1789, the newly elected Washington asked Randolph to be his Attorney General. When Hamilton and Jefferson squared off during Washington’s first term, Randolph pleased the President by trying to conciliate the two men.

After Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State, he suggested Randolph as his temporary successor, warning that with his financial problems Randolph was not independent enough to have the job for good. But Washington did not want to eject the last remaining non-Federalist in his Cabinet. Halfheartedly he made Randolph his Secretary of State. Now, as Randolph waited in the other room of Washington’s house, Pickering explained that two weeks earlier George Hammond had shown Wolcott a packet of dispatches from the French minister in Philadelphia, Joseph Fauchet, captured from a French battleship.

Pickering told Washington the documents showed that Randolph had divulged state secrets to Fauchet and asked him for a bribe to tilt American foreign policy toward France. He said they also showed that Randolph had secretly helped to incite the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, against a federal liquor tax in Pennsylvania, which the President had quashed with fifteen thousand troops.

Half-fluent in French, Pickering had scrawled out a rough English translation of Fauchet’s messages, which he now handed to the President. Washington gave Pickering no hint of his reaction to his astonishing charge. Solemnly he said, “Let us return to the other room to prevent any suspicion of the cause of our withdrawing.”

Late that night, after Randolph and Pickering were gone, Washington was alone in his darkened mansion, except for the servants. Staggered by Pickering’s revelations, he had to decide by himself whether his top appointee was a new Benedict Arnold. He did not call for expert advice, or even for a better translation of Fauchet’s dispatches.

In the absence of some magic document that would clear Randolph, Washington had to assess the damage of throwing him into a long, public trial. Even if Randolph were found innocent, many Americans and Europeans would suspect that Washington’s chief diplomat had sold himself to a foreign power: for all Washington’s pretensions about republican virtue, the U.S. government would have revealed itself as no cleaner than the Old World regimes.

Already rocked by the national commotion over Jay’s Treaty, Washington knew his administration might not survive such a scandal.

Two centuries later, it is still impossible to establish whether Randolph was guilty. Like many diplomats, Fauchet may have exaggerated for the home office his craftiness in squeezing secrets out of the Secretary of State. While talking to Fauchet, trying to build a relationship, the clumsy Randolph may have also exaggerated his eagerness to help France. Missing from the French documents was Dispatch Number Six, which supposedly proved that Randolph had sold himself for cash.

Washington knew that the British had the motive to fabricate a case against Randolph, who did not share the Federalists’ Anglophilia and was advising the President to go slow on Jay’s Treaty. But Washington also realized that Randolph had ample motive to solicit a bribe. Feeling more cash-poor than ever, the man had recently complained he could no longer entertain or use his carriage.

The President darkly noted how Randolph had been dragging his heels on Jay’s Treaty. The Secretary of State’s insistence that the treaty be renegotiated would mean no deal with the British for at least a year, which would delight the French—and the Jeffersonians who supported France.

Before the morning light shone into Washington’s upstairs bedroom, he had made two important decisions. First, he would sign Jay’s Treaty immediately. If the Randolph scandal was about to explode, he did not want to leave the treaty hanging. But he would insist that the British drop the despicable Article Twelve.

Second, he would fire Randolph, but not yet. If provoked, the Secretary of State would be in a position to scuttle Jay’s Treaty. Better to keep Randolph ignorant of the President’s suspicions against him. Only after Randolph sent the executed treaty to London would Washington pounce.

On Tuesday, August 18, Washington put his elegant signature on Jay’s Treaty and had Randolph send it to Minister Hammond. The next morning, he summoned Randolph to the President’s House. Randolph was startled to find Washington talking gravely with Wolcott and Pickering. The President gave him one of Fauchet’s dispatches: “Make such explanations as you choose.”

Schooled in French, Randolph studied the document while the others watched. As Pickering later recalled, the President “desired us to watch Randolph’s countenance” and “fixed his own eye on him.” Pickering had never seen Washington’s eye “look so animated.”

After more than half an hour had passed, Randolph denied that he had said anything “improper” to Fauchet, or taken any money from him. If allowed to examine the dispatch further, he could “throw my ideas on paper.”

“Very well,” said Washington. “Retain it.” He asked Randolph to leave the room.Seretary

Wolcott and Pickering told him Randolph had looked embarrassed but showed no clear sign of guilt. When Randolph rejoined them later, he shrieked, “I could not continue in the office one second after such treatment!” and ran down the stairs and out of the Presidential mansion.

The next day, Randolph sent him a scorching resignation: “Your confidence in me, sir, has been unlimited. . . . My sensations then cannot be concealed when I find that confidence so immediately withdrawn without a word or distant hint being previously dropped to me!”

Writing a fellow Jeffersonian, James Madison, Randolph compared the President to a Roman tyrant: “I feel happy at my emancipation from attachment to a man who has practiced on me the profound hypocrisy of a Tiberius and the injustice of an assassin.” Before Christmas 1795, Randolph published a 103-page pamphlet, entitled Vindication, in which he tried to destroy his old boss.

Beneath Washington’s “exterior of cool and slow deliberation” was a small mind that “rapidly catches a prejudice and with difficulty abandons it,” he wrote. He claimed that Washington had signed Jay’s Treaty so abruptly because he was growing senile and wanted to give selfish advantage to the Federalists.

Thumping a table, Washington cried (according to one witness) that Randolph, “by the eternal God,” was “the damnedest liar on the face of the earth!” He bemoaned his stupidity in appointing Randolph—and bursting with epithets, he hurled his copy of Vindication at the floor.

The obtuse Randolph did not understand that he could never battle the Hero of the Revolution over personal honor and expect to win, even in a political climate electrified by Jay’s Treaty. Gleefully Wolcott plunged a knife into Randolph’s back, announcing that the former Secretary of State had taken official money. Barred from evidence that might have cleared him, Randolph had to pay the government fifty thousand dollars (about a million dollars today), which plunged him into semipoverty. When America’s second Secretary of State died in 1813, he was so forgotten that his hometown, Richmond, paper reported his death in only four sentences.

In December 1795, Washington arrived at Congress Hall to deliver the annual report required by the Constitution. Thanks to the battle over Jay’s Treaty, it was the first time the President addressed the House and Senate “without a full assurance of meeting a welcome.” He insisted that Jay’s pact would keep “external discord” from disrupting “our tranquility.”

Caught off guard by the commotion over Jay’s Treaty, powerful Federalist tycoons rolled into gear. New York firms stopped issuing ship insurance until the treaty was enacted, making the Atlantic safer. Maryland Federalists drew up petitions, crying, “It is time for Baltimore to save the republic!” In Philadelphia, debtors were pressured by their banks to support the treaty. James Madison complained it was “like a Highwayman with a pistol demanding the purse.”

By early 1796, the tide had turned in favor of Jay’s Treaty. Britain scrapped its Provision Order and accepted the President’s version of their deal. Afraid that Jay’s Treaty would spur an Anglo-American attack on Spaniards in North America, Spain had recognized the Thirty-first Parallel as America’s southern border. Americans could now navigate the Mississippi River unharmed and trade from New Orleans.

House Republicans tried to withhold the ninety thousand dollars required to enact the treaty. John Adams feared a Constitutional crisis, writing Abigail that if the House denied the money, it was “difficult to see how we can avoid war” with Britain, which might lead to an American “civil war” between the Anglophile Northeast and Southern Francophiles.

Muscle-flexing House Republicans now refused to recognize Washington’s Birthday, which they derided as the nation’s “Political Christmas.” House Republicans demanded that Washington release all documents related to the diplomatic bargaining over Jay’s Treaty,. . If Washington surrendered, the House might try to grab more power from the President and the Senate.

The showdown came on Wednesday, March 30, 1796. In a message read aloud, Washington reminded the House that the Constitution gave responsibility for treaties to the Senate, whose fewer members were more likely to protect national secrets. He said the only way the House could claim wholesale access to executive documents was to impeach him, adding that “no part of my conduct” had shown a desire “to withhold any information” required by the Constitution. Republicans were outraged. John Adams felt “a few outlandish men” in the House were “determined to go all lengths.”

Then, with petitions and subtle threats, the Federalist machine pushed Maryland’s Samuel Smith and other House Republicans to reverse themselves, citing harm to the Constitution. Watching from Monticello, Thomas Jefferson wondered whether secret British bribes were behind his fellow Republicans’ cowardice.

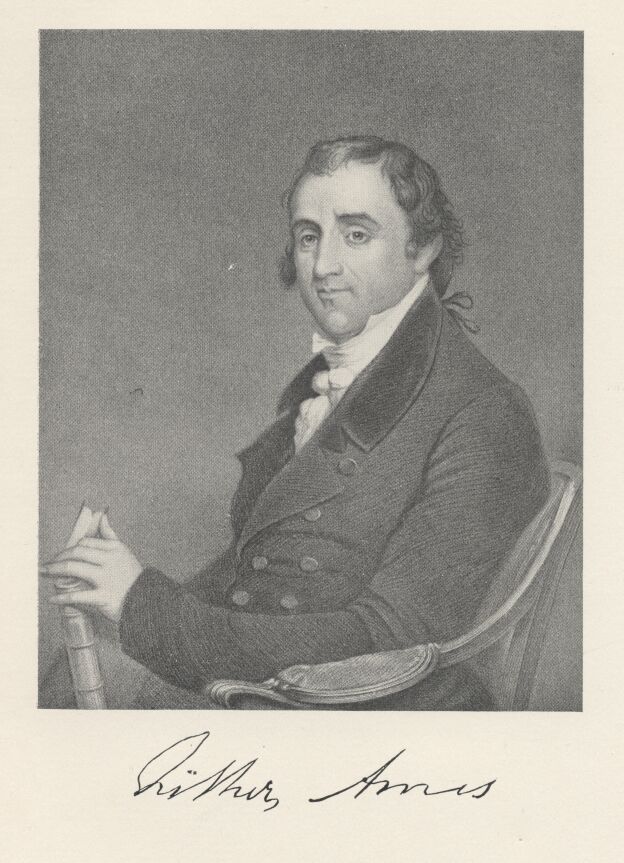

On Thursday, April 28, 1796, Federalist Fisher Ames limped onto the House floor. Confined to his house in Dedham, Massachusetts, by severe infection, Ames had been presumed near death. Members gasped as he pulled up his wasted frame. Ames said in a quavering voice, “Mr. Chairman, I entertain the hope—perhaps a rash one—that my strength will hold me out to speak for a few minutes.”

Without notes, he delivered a tour de force later remembered as one of the most powerful speeches in American history. One witness recalled that Ames “threw a spell over the senses, rendering them insensible to every thing but himself.” Ames acknowledged that critics found Jay’s Treaty “bad—fatally bad.” But a “treaty is the promise of a nation. . . . Shall we break our faith?” After ninety-minutes of oration, he fell exhausted into his chair. The chamber was silent but for the weeping of both Republicans and Federalists.

When the House finally voted on funding Jay’s Treaty, the result was a 49 to 49 tie. Chairing a Committee of the Whole, the tiebreaker would be Republican Frederick Muhlenberg, a German-speaking Lutheran pastor from Pennsylvania. Republicans were jubilant. The previous summer in Philadelphia, when a copy of Jay’s Treaty had been burned on Minister Hammond’s doorstep, Muhlenberg was one of the protestors. But now Muhlenberg shocked everyone by supporting the treaty, committing political suicide.

Bursting with gratitude, Washington thanked Fisher Ames over dinner at his residence and had his private secretary escort the ailing Congressman to recuperate at Mount Vernon. The President wrote his plantation overseer to expect “a respectable member of Congress (traveling for his health),” insisting that Ames be “well treated while he stays.”

Washington wrote John Jay he had ridden out “the Storm” but could never forget the “pernicious” figures “disseminating the poison” against him. The experience had “worn away my mind,” making “ease and retirement indispensably necessary.” Washington confided to Jay that unless some crisis made it “dishonorable,” he would not seek reelection. He was eager to stop being “buffitted in the public prints.”

By fighting for Jay’s Treaty, Washington gave his country a gift that was almost as important as his victorious Revolutionary command—the gift of peace. No other leader could have pushed the treaty through Congress. Even the great Washington almost fell short.

Under Jay’s Treaty, the British evacuated their posts in the Northwest Territory, allowing Americans to discover the rich possibilities of the new West. As Washington had dreamed, the country could seize “command of its own fortunes.” And just as he had predicted, by the time Americans fought England in the War of 1812, they were powerful enough to win.

The precedent Washington set with his leadership on Jay’s Treaty was that a President should not merely preside. He must use his unique standing—even if it made him unpopular or cost an election—to convince Congress and the American people to accept unpopular notions that may be in their long-term interest.

The Constitution did not include this conception of the Presidency. But by his deeds, Washington encouraged Americans to measure his successors against his standard of self-sacrifice, risking his good name to fight for a much-reviled treaty that he thought essential for his young country to survive.

Martha Washington later insisted that Jay’s Treaty hastened his death. Content to let history provide his reward, he wrote, “I have a consolation within that no earthly efforts can deprive me of, and that is, that neither ambitious nor interested motives have influenced my conduct.” The arrows of malevolence, therefore, however barbed and well pointed, never can reach the most vulnerable part of me.”