Once the most famous Chinese dish in America, chop suey helped spur the growth of Chinese restaurants. A Smithsonian curator is now criss-crossing the country to research its beginnings.

-

Fall 2017

Volume62Issue5

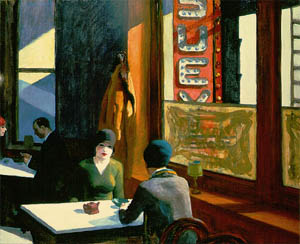

It’s winter of 1939 and the big, bamboo-style letters on the sides of a building at Broadway and 49th Street blaze forth the name “CHIN LEE” late into the night. Around them, the words “DINING,” “DANCING” and “NO COVER CHARGE” are spelled out by blinking yellow bulbs. The entrance is on 49th Street, under a movie-theater-style awning that lures you up a brightly-lit flight of stairs to a coat check, a crowd of people milling about and the clatter of plates and the noise of a frantic jazz band.

Finally, the unsmiling Chinese maître d’ nods your way, pulls menus off a pile and leads you through a maze of tables crowded with shouting, smiling, eating diners. He finds you a table off in a far corner and disappears, leaving you to survey the surroundings. On the main floor, dozens of white-clothed tables surround a dance floor and an all-Chinese jazz orchestra wailing away at breakneck pace, while above there’s a second floor, with more tables and a balcony overlooking the dancers.

On the dance floor, it’s strictly catch-as-catch-can, with gum-chewing shopgirls from Gimbel’s dancing with shopgirls, while Wall Street clerks look on hungrily, and a gaggle of girlfriends from the Bronx tries to catch the eyes of a group of slumming Princeton boys. A black-bow-tied Chinese waiter hands you the menu for the 70 cents dinner, and you scan the choices. You can have a club sandwich or a ham omelet, if you must, but the top of the menu lists Chin Lee’s specialties, which are chow mein and chop suey--six kinds of “chop sooy” to be precise. You look around at the other tables and see big platters heaped with steaming mounds of brownish stew, either over rice, for chop suey, or noodles, for chow mein.

The kitchen churns out hundreds of gallons of the stuff daily, to be shoveled down by hundreds of thousands of happy customers every year. It’s the midpoint of the Chop Suey Era in American dining, and you want to share in the fun. You signal the waiter, point to the beef chop suey on the menu and say, “I’ll have some of that.”

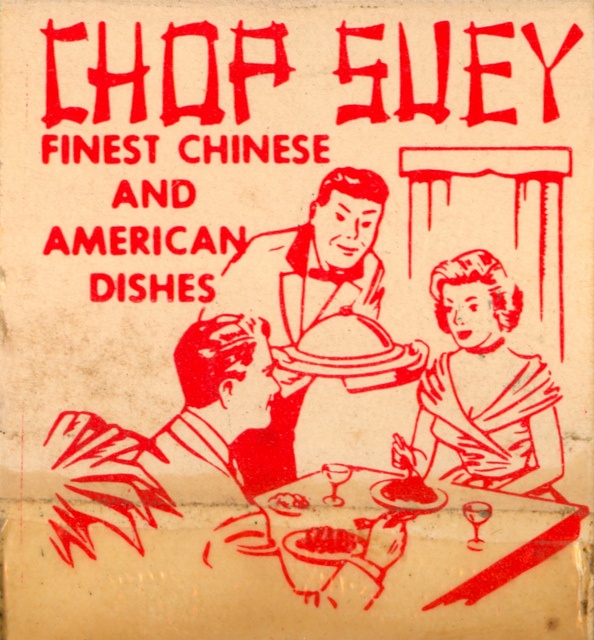

Today Chin Lee is a near-forgotten part of the city’s culinary memory, its Theater District building now covered with giant billboards, and a Latin nightclub occupying the upstairs space. In fact, to view the only concrete evidence that the chop suey palace even existed, you have to go down to Chinatown. Among the exhibits in “Have You Eaten Yet?: the Chinese Restaurant in America” at the Museum of Chinese in the Americas are a souvenir fan and a couple of menus from “Broadway’s Most Popular Chinese-American Restaurant.” They’re part of the eccentric collection of a Chinese food fanatic named Harley Spiller, who has spent the last eight years collecting ephemera—from menus to matchbooks, cookbooks to song lyrics—all relating to the Chinese-American culinary experience.

Today Chin Lee is a near-forgotten part of the city’s culinary memory, its Theater District building now covered with giant billboards, and a Latin nightclub occupying the upstairs space. In fact, to view the only concrete evidence that the chop suey palace even existed, you have to go down to Chinatown. Among the exhibits in “Have You Eaten Yet?: the Chinese Restaurant in America” at the Museum of Chinese in the Americas are a souvenir fan and a couple of menus from “Broadway’s Most Popular Chinese-American Restaurant.” They’re part of the eccentric collection of a Chinese food fanatic named Harley Spiller, who has spent the last eight years collecting ephemera—from menus to matchbooks, cookbooks to song lyrics—all relating to the Chinese-American culinary experience.

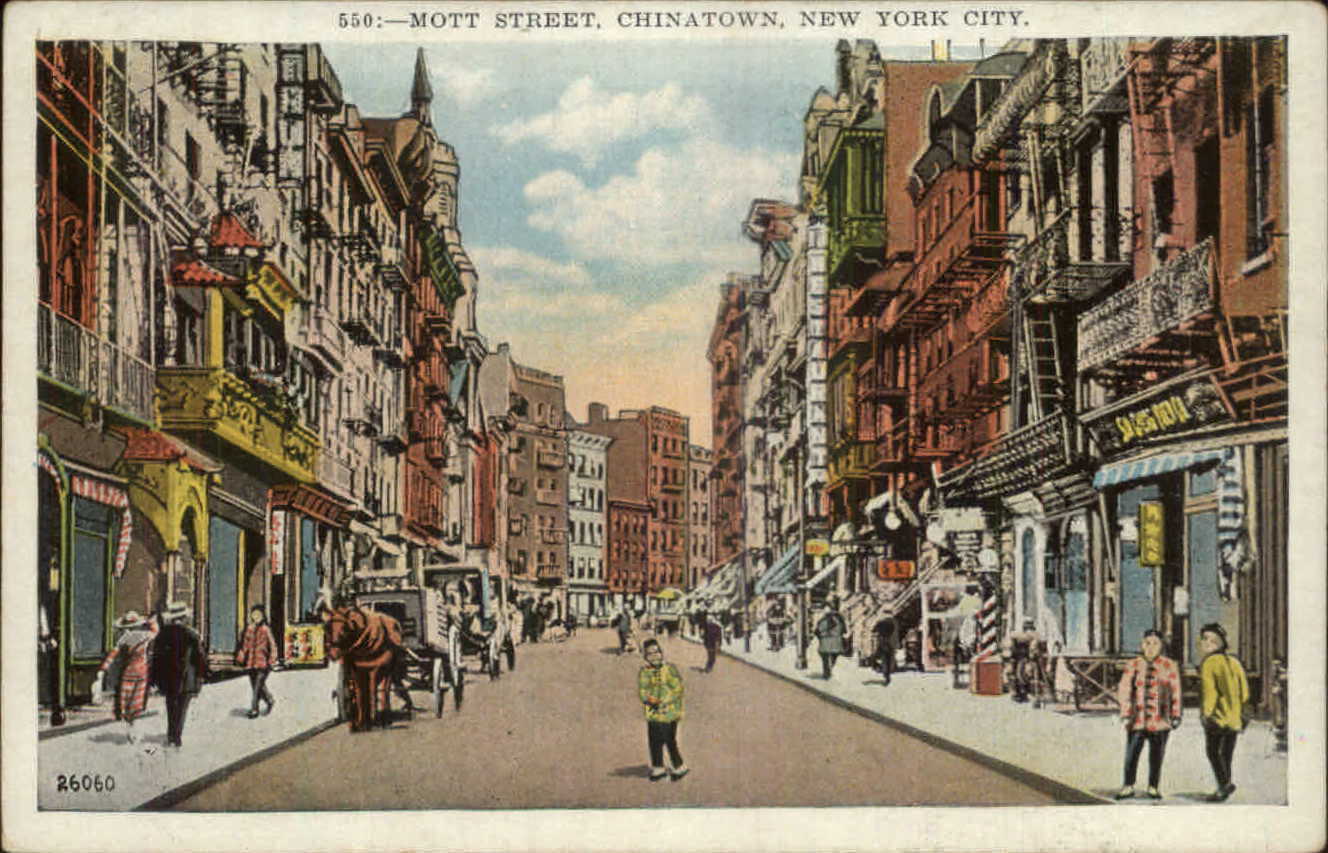

You can also see century-old menus from Chinatowns in Boston and New York; a hand-colored postcard of Mott Street in the 1940s, when nearly every restaurant had a neon sign blazing “CHOP SUEY” or “CHOW MEIN” above its door; marvel at the inanity of Ideal Toy’s 1967-vintage “Chop Suey” game; and listen to Louis Prima and Keely Smith singing, “Chop Suey, Chow Mein, Tufu [sic] and you, I’ve got the craziest yearning...”

It’s never quite stated in the exhibition, but all of these artefacts have a common theme: From 1920 through the 1960s, Chinese-American restaurants were the most exciting culinary experience in town, when no other ethnic food could compete with the roster of chow mein, egg rolls, fried rice, shrimp toast, spare ribs, egg foo young and, above all, chop suey itself. Then without anybody noticing it, the Chinese-American restaurants began to disappear, the signs blinking out one by one. And this all leads to the question of, what was that culinary craze? Where did it come from and why did it go?

You have to look hard to find chop suey, shrimp toast and the other Chinese-American specialties in Manhattan today. Only one, lonely “CHOW MEIN” sign remains, flickering above the entrance to Jade Mountain on 2nd Avenue and 11th Street. At age 74, this is the second oldest Chinese restaurant in the city (outranked only by Doyers Street’s Nom Wah Tea Parlor, est. 1925). Inside, its menu, decor, atmosphere and staff all appear to have been unchanged in decades, except for a certain dimming with age. You can take your choice of booths, upholstered in worn, caramel-colored vinyl, then peruse the well-thumbed menu. If you want to try and recreate the excitement of Chin Lee in its heyday, or its food at least, you can look down to the chop suey section and pick whichever you like.

The waiter will soon bring out a pedestaled dish under a battered metal dome and remove it to reveal what once defined Chinese food in American minds: A thick brown sauce, mainly watered-down chicken stock congealed in corn starch. A muddle of overcooked ingredients that probably included roast pork, bean sprouts, Chinese cabbage, snow peas, onion, canned mushrooms, bamboo shoots and water chestnuts. And no flavor whatsoever, except for an undefined savoriness. Chop suey isn’t vile or unpleasant, but it doesn’t have any positive qualities either. It’s simply bland, generic fuel for filling one’s stomach. How did American fall in love with dishes like this? Was this really Chinese food, or something invented in America?

“Chop suey is Chinese food, made by Chinese,” Jade Mountain’s waiter will tell you. “Only they make it different here because the ingredients are different.”

Most tales about Chinese-American food, and chop suey in particular, are based on the “fakelore” all too common in culinary history. But Jade Mountain’s waiter is more right than not.

The story begins in China, in a group of poor and obscure coastal counties in Guangdong Province that, for simplicity’s sake, we’ll call the Toisan region. Many of its residents were peasants, eking out a living from overpopulated land and suffering under periodic economic crises and civil unrest. Vegetables were their principal crops, but they also raised pigs and a variety of fowl, of which they consumed every possible part from beak to hoof. While the elites up in the provincial capital of Guangzhou enjoyed the refined dishes and elaborate banquets of Cantonese cuisine, Toisan’s peasants lived mainly on mixed vegetable dishes and fried noodles. But it was the Toisanese who migrated by the thousands to the United States and dominated the early American Chinatowns, so it was they who defined “Chinese” food for most Americans.

Beginning in 1848, the first mass migrations of Chinese began to land in North America, mostly to work in the California Gold Rush. Whites at first tolerated the Chinese, even trying the “curries, hashes, and fricassees” of their cuisine, but soon turned against the pig-tailed foreigners, seeking to expel them, with violence if necessary, from all Western territories. Whites shunned the region’s Chinatowns and boycotted Chinese restaurants as depraved and injurious to “civilized” sensibilities. (They did, however, eat American food prepared by Chinese servants.) Consequently, while it’s probable that California’s Chinese ate chop suey, there exists no contemporary mention of the dish on the West Coast before 1900. For the first American use of the term, we have to follow the trail of Chinese escaping East and head to the great immigrant mixing bowl of New York City.

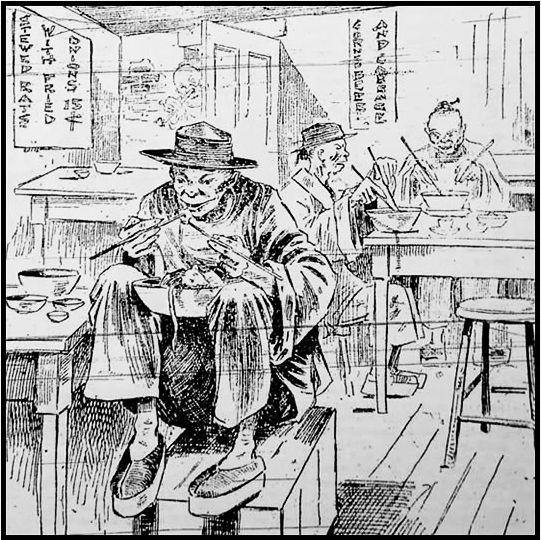

New Yorkers may have been as racially biased as Californians, viewing the Chinese as bland, sinister, inscrutable, pigtailed, opium-smoking, eaters of rats. (A street ditty even went: “Chink, chink, Chinaman/Eats dead rats,/Eats them up/Like gingersnaps.”) But they did not see the Chinese as an imminent threat and allowed them to settle along lower Mott and Pell Streets in the beginnings of Chinatown. New Yorkers drew the line, however, at eating in the city’s first Chinese restaurants--who knew what floated in their incomprehensible stews! In the summer of 1883, these fears came to a head when a local doctor charged a Mott Street grocer with cooking rats and also cats in the rear of his store. Like flies, reporters swarmed to Chinatown, but a sanitary inspector discounted the doctor’s testimony, absolving the grocer. Nevertheless, the charges infuriated the editor of the city’s first Chinese-language newspaper.

Wong Ching Foo, a renowned defender of Chinese rights, offered a $500 reward to anyone proving that the Chinese ate rats or cats. When no takers appeared, he wrote an article for the Brooklyn Eagle extolling the breadth and sophistication of Chinese gastronomy. Point by point, he compared it with American food, concluding that, “In the main Chinese cooking is better and cheaper than our own.” His proofs were better cooking methods, a broader range of ingredients and a list of favorite Chinese dishes, including something called “chop soly,” a ragout which he claimed was the national dish of China: “Each cook has his own recipe. The main features of it are pork, bacon, chickens, mushrooms, bamboo shoots, onion and pepper. These may be called characteristics; accidental ingredients are duck, beef, perfumed turnip, salted black beans, sliced yam, peas and string beans.”

Wong Ching Foo’s article awakened the appetites of New York City’s Bohemians, a group of ne’er-do-well artists and intellectuals who were the foodies and chowhounds of their day. Rather than gather at haute cuisine palaces like Delmonico’s, they preferred to carouse down in the immigrant districts, “discovering” the city’s low-rent German, Italian, French, Hungarian and Jewish eateries. During the 1880s, they also began to visit Chinatown restaurants. One such trip was described by the journalist Allan Forman, who was invited by a lawyer of “decidedly Bohemian tendencies” to dine in Chinatown. Forman knew the lawyer’s “penchant for mousing into all sorts of out-of-the-way quarters of the city, where he fairly reveled in dirt and mystery and strange viands.” When he heard their destination was Mott Street, however, he wavered:

“Thanks awfully. But my palate is not educated up to rats and dogs yet. Let me take a course in some French restaurant where these things are disguised before I brave them in their native honesty.”

But the lawyer agreed to treat him to dinner at Delmonico’s if the Chinese restaurant wasn’t “as clean as that Italian place where you eat spaghetti.” So on a cold New York night the two traveled down to Mong Sing Wah’s restaurant, up some stairs off a courtyard behind 18 Mott Street. There Forman watched in amazement as his friend conversed in apparently fluent Chinese: “`Chow-chop-suey, chop-seow, laonraan, san-sui-goy, no-ma-das,’ glibly ordered my friend, and the white-robed attendant trotted off and began to chant down a dumbwaiter.” Forman had no idea what was on the menu, but when the food appeared he seems to have forgotten his fears about rats and dogs.

After a short lesson in chopsticks from a Chinese man at the next table, the two adventurers dug in:

“Chow-chop suey was the first dish we attacked. It is a toothsome stew, composed of bean sprouts, chicken’s gizzards and livers, calfe’s tripe, dragon fish, dried and imported from China, pork, chicken, and various other ingredients which I was unable to make out.”

By the end of the feast, which had been washed down with tea and little cups of sweet Chinese firewater, Forman was amazed to find that, “The meal was not only novel, but it was good, and to cap the climax the bill was only sixty-three cents!”

Over the next decade, the trickle of Bohemians and other tourists to Chinatown became a stream. They visited usually as part of “slumming” parties, looking for outlandish scenes, a whiff of danger and chop suey. According to Leslie’s Weekly, “It is the seductive dish that calls back again and again the American to Chinatown. An American who once falls under the spell of chop sui may forget all about things Chinese for weeks, and suddenly a strange craving that almost defies will power arises and, as though under a magnetic influence, he finds that his feet are carrying him to Mott Street.”

The chop suey that they consumed was far earthier than anything served at Jade Mountain. Although Wong Chin Foo emphasized chop suey’s variability, by the 1890s the dish had already had acquired a fixed roster of ingredients. It was a stew of chicken livers and gizzards and bits of tripe, cooked with mushrooms, bamboo shoots and bean sprouts, and maybe adding celery, onions and “dried dragon fish.” Chop suey’s main seasoning was “seow,” also known as soy sauce, then utterly exotic. There was nothing “American” about the dish; it hadn’t yet been altered to please white tastes. In fact, from the organ meats and the assortment of vegetables, this chop suey still sounds very much like the kind of edible, peasant miscellany favored in Toisan.

But how did chop suey jump from 1890s Chinatown to, say, Bill Hong’s on East 56th Street, where they serve what may be the most expensive chop suey on the planet? Bill Hong’s is the last of the big Theater District Chinese-American restaurants, like Chin Lee, House of Chan and the original Ruby Foo’s, that thrived from the 1920s through the 1950s. Photos of dozens of celebrities still stare down from the walls--most prominently Michael Jackson, who’s apparently a regular. But the elegant, spacious interior, all grey and white, is often nearly empty, except for the hovering waiters in white jackets and black bowties. Most of their clientele is elderly, according to the manager, and Sunday is the only time the restaurant is really crowded, when “it’s like a Jewish convention.”

It’s a dubious proposition that the more expensive the dish the better it must be, but you can order the shrimp chop suey at Bill Hong’s, costing a breathtaking 19 dollars a portion. When the dish arrives and the dome is popped off (with a lot more ceremony than at Jade Mountain), the shrimp are indeed large and succulent. But what lies beneath them is what you’d expect in American chop suey, i.e. nothing remarkable: a bed of flavorless vegetables bound together by a watery pale sauce. That, according the Chinese cookbook writer M. P. Lee, is precisely the point: “The reason for [chop suey’s] popularity is probably that it has no strong flavor or taste of any kind, and is therefore more easily acceptable to Western palates.” Even a spoonful of hot sauce can’t redeem the dish. Once a group of Mainland Chinese came to Bill Hong’s and ordered a meal. When the food arrived, they looked up at the waiter in outrage and asked: “What the hell is this? You expect us to eat this?”

So what happened between the 1890s and today? The answer begins with a tale that Bill Hong’s manager tells about the “invention” of chop suey.

“The story,” he says, “maybe not true, but I believe it, is that the Chinese foreign minister, Mr. Li, came to represent China in America. Guests come to see Mr. Li in his hotel, his chefs don’t have time to prepare a dish, so they make a mixed vegetable dish and call it ‘chop suey.’ The guests were so happy that they put the recipe on the menu.”

“The story,” he says, “maybe not true, but I believe it, is that the Chinese foreign minister, Mr. Li, came to represent China in America. Guests come to see Mr. Li in his hotel, his chefs don’t have time to prepare a dish, so they make a mixed vegetable dish and call it ‘chop suey.’ The guests were so happy that they put the recipe on the menu.”

There really was a Mr. Li, actually the Chinese statesman Li Hung Chang, who in 1896 made a highly ballyhooed official visit to the United States. When he landed in New York, every local paper stuffed its pages with details about the city’s guest, from his exotic dress down to his opinion on whether women should ride bicycles. Reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal were particularly interested in what Li ate, peering over the shoulder of his personal chefs as they prepared meals in the Waldorf kitchen and recording every morsel that passed his lips at public functions. Aside from a few spoonfuls of consommé and some plain fish, Li disliked Western food and neglected even to dine in Chinatown (perhaps reflecting the fact that he represented the top of Chinese imperial society, while New York’s Chinese were from, well, Toisan). Instead, he relied almost totally on his chefs, and the one dish they never prepared was chop suey.

Nevertheless, the Journal’s reporters couldn’t help linking Li Hung Chang with the Toisanese peasant dish. Never mind about the vast cultural gulfs separating Peking from Toisan and China’s high officials from its peasants. Li Hung Chang was Chinese and chop suey was Chinese, so he must have eaten chop suey. A few days after Li’s departure, the Journal ran a full-page profile of his chef, billing him as “The Greatest Chicken Cook In The World.” Below, readers found 19 recipes, perhaps the earliest Chinese recipes printed in the United States, claiming to represent the “Queer Dishes Served At The Waldorf.” Among them was “Chow Chop Sui,” also known as “Fricasseed Giblets,” which the accompanying Chinese characters identify as “stir-fried mixed bits,” or chou tsap sui.

The writer tells us that it can be made with a multitude of ingredients, “to rival in heterogeneity the far-famed boarding-house hash,” but then makes a startling admission: “The most popular of the Chinese fricassees has already gained some celebrity in America.” In other words, there was nothing new about chop suey. In fact, there was nothing new about any of the “queer dishes” in the article. They’re all Cantonese classics like bird’s nest soup and egg foo young that were mainstays of the fancier Chinatown restaurants--one of which was the likely real source of these recipes.

New Yorkers didn’t care. All they knew was that, in the wake of Li’s visit, everything Chinese was the rage. They crowded Chinatown to gawk at the locals, buy curios, sample tea and eat Chinese food. The Brooklyn Eagle predicted that “the pretty hostess, arrayed in a rich yellow silk Li Hung Chang jacket, whose loose sleeves will show to such good advantage her shapely arms, presiding over a Chinese dinner, may be one of the charming sights in fashionable society this winter.” Chinese food became so popular that Chinatown restaurateurs saw their chance to expand out of their tiny neighborhood, opening eateries on the Bowery and then up the other main avenues all the way to Harlem. The menus of these “chop sueys,” as Chinese restaurants were now known, didn’t offer the variety found in Chinatown, serving strictly what their white customers wanted, such as chop suey, chow mein, egg foo young and “yakoman,” a noodle soup topped with shredded meat and hardboiled eggs.

As Chinese food moved out of Chinatown, restaurant owners altered the dishes to confirm to the tastes of their new customers. The livers, gizzards and tripe in chop suey had been a little too easy to mistake for rat or cat meat, so the “fricasseed giblets” were replaced by easy-to-identify pork, chicken or beef. The wide variety of possible vegetables was reduced to a fixed roster of bean sprouts, celery, water chestnuts, bamboo shoots and onions. Dried cuttlefish and dragon fish were now only available in Chinatown, to Chinese. And most importantly, the cooks Americanized their cooking methods. The Chinese liked their vegetables “underdone,” i.e. crisp, bright and flavorful, but that wasn’t to the taste of most New Yorkers. They expected anything green in its natural state be cooked until it was gray, mushy and insipid, and that included the vegetables in their chop suey. Overcooked and cut off from its earthy roots, this new, “improved” chop suey became the founding dish of Chinese-American cuisine.

How did American-style chop suey take the country by storm? It’s hard to believe, based what’s served at Jade Mountain and Bill Hong’s, that the dish had won over millions of palates simply by taste. However, we can never know exactly how those chefs of a century ago prepared the dish. Maybe it wasn’t always flavorless and uninspired. It’s time for another expedition, up to Riverdale in the Bronx, home to one of the last populations with a taste for chop suey and chow mein, i.e. Jewish senior citizens. Small but clean, brightly lit and busy, Golden Gate sits along a shopping strip largely made up of kosher delis, supermarkets and Chinese restaurants. Although the menu contains all the Chinese-American classics, Golden Gate manager Kenny Yao and most of his staff come from Toisan, where they remember the dishes in their native state.

“Chop suey means ‘mixed pieces,”‘ he will tell you. “It’s home-style food in Canton province, not restaurant food, a mixed vegetable dish with bok choy, baby corn, snow pea pod.”

For most restaurateurs, chow mein and chop suey are exactly the same, only one is over rice and the other over fried noodles, but Kenny says that in Toisan there are distinctions between the dishes. Bean sprouts are fine for chow mein, he says, but not chop suey, and in chop suey the vegetables should be “crisp, crisp,” while chow mein’s should be overcooked. If you order the chicken chop suey, the vegetables will probably be, well, not so crisp, but what you will really notice is the sauce: delicate, flavorful and rich with chicken.

“That’s a Cantonese white sauce,” says Kenny. “Now Chinese chefs cover everything with the same brown sauce, to hide old vegetables and old meat. The white sauce is healthier but harder to make.”

A great sauce, as the French know, can hide a multitude of sins. Even if the versions served at Jade Mountain and Bill Hong’s didn’t please your taste buds, there’s no guarantee, but you may actually enjoy eating this chop suey, overcooked vegetables and all. The hands of a skilled professional, like the man behind stove at Golden Gate, can make chop suey can taste good. Maybe, like too many dishes, it has been a victim of its own popularity, prepared by cooks who didn’t know or care enough to make it properly.

We’ll give turn-of-the-century chop suey chefs the benefit of the doubt. But that doesn’t completely tell us why New Yorkers fell so hard for the dish. (One half-joking theory had it that Chinese laced the dish with “dope,” i.e. opium, to make it irresistible.) One answer is that diners were bored with “the insipidity of cheap chophouses and the sameness of dairy restaurants.” In an era of change and expansion, they wanted to try something alien and exciting, and chop suey, made with weird ingredients like bean sprouts, water chestnuts and soy sauce, fit the bill perfectly. The dish was also cheap, costing as little as 15 cents a bowl, which made it attractive to the masses of laborers and immigrants living in the city’s sprawling slums. And chop suey satisfied its consumers, not just stuffing their stomachs but giving them a deeper feeling of fulfillment, and this links it to an important part of Western culinary tradition. Since at least Roman days, peasants and urban laborers subsisted on savory jumbles of ingredients boiled down to indecipherability: mushes, porridges, burgoos, hodgepodges, ragouts, olla podridas and the like. Perhaps in chop suey we taste a bit of the same primal stew that has fueled us for so many centuries.

Also crucial to the dish’s success was the setting in which they served chop suey--what restaurant management types like to call the “concept.” Chinese restaurants did their best to produce an alien and exotic scene that set them apart from all the other eateries. The new Uptown chop sueys ran from side street storefronts to fancy palaces like the one on Longacre Square that attracted the rich, post-theater crowd. Inside, customers were enveloped by an aura of Oriental mystery created by dim lights, silk lanterns, Chinese scrolls, pin-ups of “almond-eyed ladies” on the walls and elaborate teak and mother-of-pearl furniture. Most chop sueys opened in the early evening and didn’t close until two or three a.m., when roisterers crowded in seeking to fill their stomachs before stumbling home to bed. They didn’t go just for the food; they also found an “entirely unconventional” environment in which the era’s expectations for decorum and “respectable” behavior had been erased.

“There is also a free and easy atmosphere about the Chinese eating house,” reported the New York Tribune, “which attracts many would-be ‘Bohemians’....Visitors loll about and talk and laugh loudly. When the waiter is wanted some one emits a shrill yell which brings an answering whoop from the kitchen, followed sooner or later by a little Chinese at a dog trot....Everybody does as he or she pleases within certain very elastic bounds.”

Reporters investigating the phenomenon were surprised to find that blacks had become among Chinese eateries’ most devoted customers, a “stout colored woman patron” telling a Tribune reporter that chop suey is the “most fillin’ thing a hungry body can eat.” In the poor district just west of the Tenderloin, blacks patronized at least a half dozen chop sueys, ranging from little storefronts to a “great barnlike place” on 32nd Street and Broadway that also attracted rough-looking whites. One journalist that the affinity between blacks and chop suey restaurants was due to the noise in the kitchen, which “reminds one of the similar condition of Southern kitchens under negro management.” That blacks were more likely to be served in Chinese-owned restaurants may also have had something to do with it.

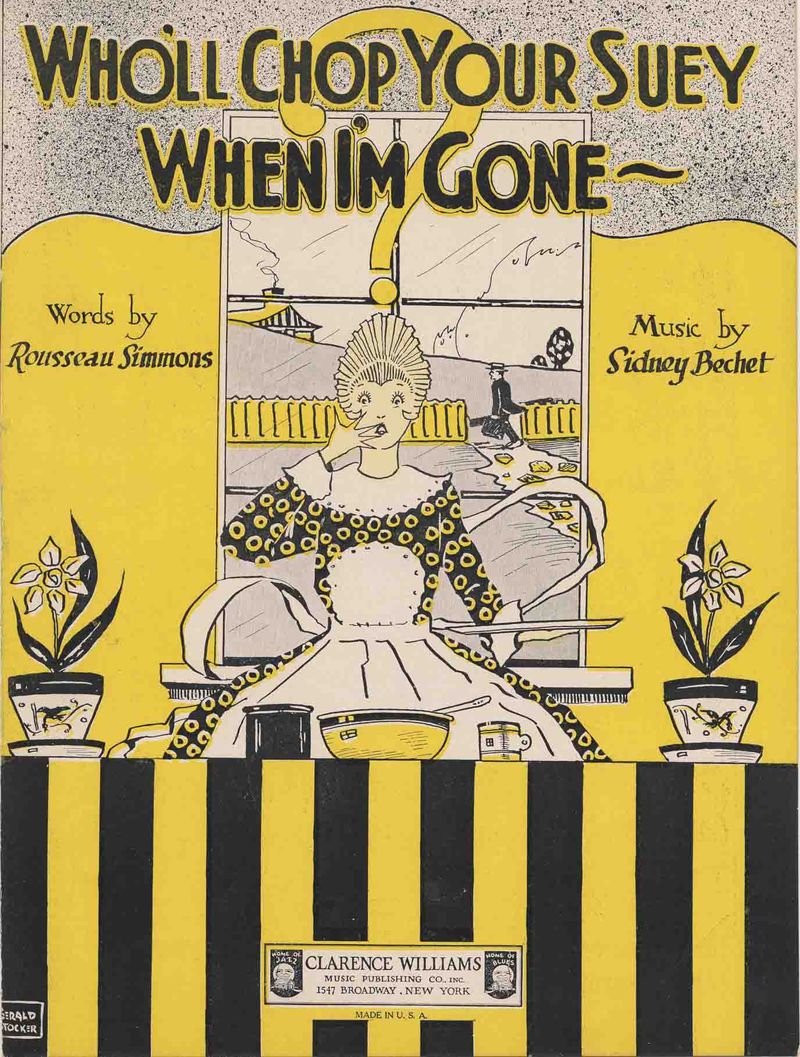

From 1900 on, Americans began to gobble down chop suey with an avidity unseen for any foreign food--even pizza and sushi don’t come close. The dish joined ham and eggs and coffee with donuts as a standard part of the urban diet, while Chinese-American restaurants began to pop up in every city and most towns across the country. Chop suey was cheap, popular and easy to make in bulk, also appearing on menus in white-owned restaurants and coffee shops and on the serving lines in cafeterias. Women’s magazines and the new Chinese cookbooks taught making chop suey at home, and if you didn’t have a Chinatown nearby for ingredients, you could always buy them in the can from La Choy or Chun King. The word “chop suey” slipped over to soda fountains, where it became a chopped dried fruit topping on sundaes; to home cooks, who made “American chop suey” as a ground beef, macaroni and tomato stew; and to music, with tunes like Louis Armstrong’s “Cornet Chop Suey” and the novelty “Who’ll Chop Your Suey When I’m Gone?”

For some, mainly educated Chinese perturbed by the description of chop suey as “the national food of China,” this fad demanded an explanation, preferably one placing the dish’s “invention” as far away from China as possible. First they revived our old friend Li Hung Chang, crediting, or blaming, his chefs for producing chop suey on the spur of the moment to feed hungry guests in New York, Washington or even Chicago and San Francisco (two cities he never even visited). Other tales give the honor to Chinese railway workers in California or an anonymous Irishman trying to make Irish stew. And then there’s the story of Gold Rush-era San Francisco, where a group of drunk miners barged into a Chinese restaurant, demanding food. To get rid of them, the cook pulled some leftovers from the garbage, cooked it up and served it to the drunks. When the miners, who loved the dish, asked its name, the cook replied: “chop suey.” Here was the dish as a kind of colossal joke: Chop suey is garbage, and we’re too stupid to realize it.

None of this mattered to the great American masses. After World War II, “going for Chinese” became a weekly ritual of suburbia, where parents greeted the waiter by his first name, and even children could master ordering “One from Column A and One from Column B.” And the dish achieved its apotheosis when it was revealed that the favorite meal of President Eisenhower, that paragon of Middle American tastes, was delivery from Washington’s Sun Chop Suey Restaurant: chicken chop suey, fried rice and egg foo young, with almond cookies for dessert. There only instructions were that the chop suey be good and hot. It seemed that nothing could dislodge chop suey from the country’s culinary pantheon.

The American palate, however, is notoriously fickle, with not even steak and potatoes secure of its place. In the mid-1960s, new laws allowed thousands of Chinese to immigrate to the United States, mainly from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Guangdong. They brought with them recipes for hundreds of exotic dishes and a completely different understanding of what meant Chinese food. Some opened restaurants whose offerings opened the eyes of food writers like Craig Claiborne to the array of regional cuisines existing in China. And after Nixon resumed relations with the People’s Republic, Americans could finally sample real Chinese cooking (or what remained of it) in China itself. Back home, people were again in the mood for adventure, and by this time there was nothing so safe and innocuous as chop suey. In New York, tastes changed to new, more strongly-flavored dishes, like General Tso’s chicken and chicken with broccoli (which turn out to have their own authenticity problems). And without anybody much noticing, chop suey began to disappear from city menus.

Today, the end seems all but certain for chop suey, to join the roster of dishes like lobster Newburg, green turtle soup, chicken a la king, mutton chops and so on, as relics of New York’s culinary past. The dish doesn’t even have much nostalgia cachet: Ruby Foo’s has been revived in the style of the big, 1930s Chinese restaurant-nightclubs, but its menu favors sushi, not Chinese-American. Chop suey hangs on in the handful of old-timers like Jade Mountain and Bill Hong’s, and in the Cuban-Chinese eateries, on the Chinese side of the menu (which nobody ever orders from out in the booming new Chinatowns of Queens and Brooklyn, they don’t have to cater to white tastes anymore, while on chop suey’s home turf of Manhattan’s Chinatown, the number of restaurants serving Chinese-American has shrunk to just two: Mott Street’s Hop Kee and the 69 Restaurant on Bayard. Instead, pedestrians are tantalized by a dizzying array of culinary possibilities, from Taiwanese to Chiu Chow, Chinese-Malaysian to Chinese-Vietnamese, bubble tea to congee, and even a kind of post-modernist Cantonese fusion. The only question is, what to eat?

Today, the end seems all but certain for chop suey, to join the roster of dishes like lobster Newburg, green turtle soup, chicken a la king, mutton chops and so on, as relics of New York’s culinary past. The dish doesn’t even have much nostalgia cachet: Ruby Foo’s has been revived in the style of the big, 1930s Chinese restaurant-nightclubs, but its menu favors sushi, not Chinese-American. Chop suey hangs on in the handful of old-timers like Jade Mountain and Bill Hong’s, and in the Cuban-Chinese eateries, on the Chinese side of the menu (which nobody ever orders from out in the booming new Chinatowns of Queens and Brooklyn, they don’t have to cater to white tastes anymore, while on chop suey’s home turf of Manhattan’s Chinatown, the number of restaurants serving Chinese-American has shrunk to just two: Mott Street’s Hop Kee and the 69 Restaurant on Bayard. Instead, pedestrians are tantalized by a dizzying array of culinary possibilities, from Taiwanese to Chiu Chow, Chinese-Malaysian to Chinese-Vietnamese, bubble tea to congee, and even a kind of post-modernist Cantonese fusion. The only question is, what to eat?

The crowded, cheerful Big Wong restaurant on Mott Street is a typical Hong Kong-style noodle restaurant, specializing in noodle soups, unctuous roast meats and plates of brilliant green choy sum, a favorite Cantonese vegetable. It’s the antithesis of Chin Lee, place where you go for the food, not the spectacle. Yet there it is, down near the bottom of the menu’s “Hot Dishes Served On Rice” section: chop suey with rice. At four dollars it won’t break the bank, so you order it, and out comes a plate of sliced pork, squid, fish cake, crab leg, chicken, shrimp, octopus and broccoli, all in a light brown sauce over rice. The dish is toothsome, if a little miscellaneous, but it’s not the chop suey of yore, the brown stew that seduced millions of American palates.

“This is Chinese-style chop suey, not American,” says Big Wong’s manager. “When they order it, the Americans complain.”

In fact, you’ll find similar dishes in noodle restaurants all over Chinatown. They call the dish “Chop Suey on Rice (Hong Kong style),” “Combination with Broccoli,” or “Mixed Meat over Rice,” but the Chinese characters always identify it as shap hwui, meaning “assorted things simmered in gravy.” The dish can include almost anything, except perhaps bean sprouts and water chestnuts, and this is one of the culinary concepts brought over by the recent waves of immigrants. As it’s understood in China, chop suey means “odds and ends,” a dish made from throwing whatever leftovers you have in the wok and cooking it up. It’s Chinese hash, and we’ll probably all be eating it that way soon enough.