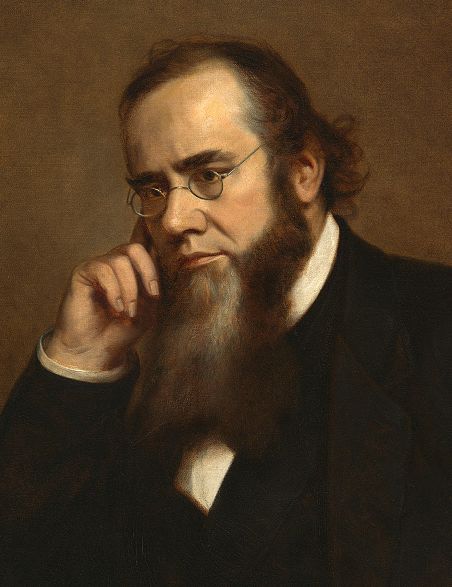

Working closely with President Lincoln, Secretary of War Stanton was indefatigable in laboring to win the Civil War. But his abruptness could sometimes be counterproductive.

-

Fall 2017

Volume62Issue5

“Good and evil were strangely blended in the character of this great war minister,” George Templeton Strong wrote a few days after Edwin Stanton died. “He was honest, patriotic, able, indefatigable, warm-hearted, unselfish, incorruptible, arbitrary, capricious, tyrannical, vindictive, hateful, and cruel.”

Strong, a New York lawyer who knew Stanton well, was right: Stanton was all of those things, a strange blend of good and evil. As the Union’s Secretary of War during most of the Civil War, he was Lincoln’s military right hand, the man whom the President referred to as his “Mars.”

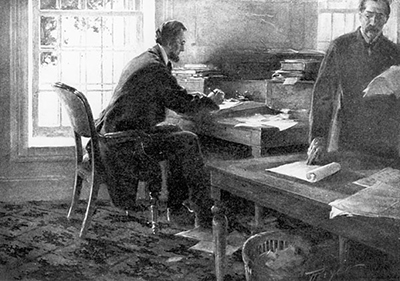

Working together in Stanton’s telegraph office, the two men received telegraphic reports from the battlefield and gave instructions directly to the generals. Stanton’s great contribution was organization: organizing the war department, the million-man army, and the northern railroads and telegraphs, to bring them all to bear against the South.

Stanton was also Secretary of War in the months and years just after the Civil War. Stanton organized the military trial of those accused in the murder of Lincoln and attempted murder of Seward, which ended in the execution of four of those involved, including Mary Surratt. Stanton transformed the Union army from a fighting force into an army of occupation, to occupy and pacify the South. Reading the almost daily reports of violence in the South, Stanton believed that the Army had to remain in the South, to protect southern blacks and Union sympathizers. President Andrew Johnson believed that the Army had to leave the South, so that southerners could govern the South. Their disagreement grew so intense that Johnson attempted to remove Stanton, which led to the impeachment and near removal of the president. So to understand the nation’s first impeachment of a president, one has to understand Stanton, for Stanton was at the center, he was the cause, of the Johnson impeachment.

Stanton was born in Steubenville, Ohio, on the banks of the Ohio River, not far from Pittsburgh, in late 1814. His father was a doctor, but his father died when Edwin was only thirteen, and as the oldest son Stanton had to work, in a bookstore, to help feed the family. A friend recalled that young Edwin was a good employee with one fault; he was often so busy reading a book that he paid no attention when a customer came in to the bookstore. Money was so tight that Stanton was only able to go to college for three terms, to Kenyon College in Ohio, and then he “read law” in order to become a lawyer. He soon became a successful lawyer, the county prosecutor for several years, and he was involved in politics, as a die-hard Democrat. Stanton’s friend and law partner, Benjamin Tappan, was a United States senator in these years, and Stanton served as his Ohio eyes and ears: giving speeches, writing resolutions, attending conventions.

Stanton married Mary Lamson in late 1836 and they had two children. Their daughter died and then, in early 1844, Stanton’s wife Mary died. For several weeks he was near madness, wandering around the house at night, wailing “where’s Mary, where’s Mary?” Two years later Stanton’s brother Darwin, a doctor, in a fit of “brain fever” used his scalpel to commit suicide. Death was a constant part of Stanton’s life.

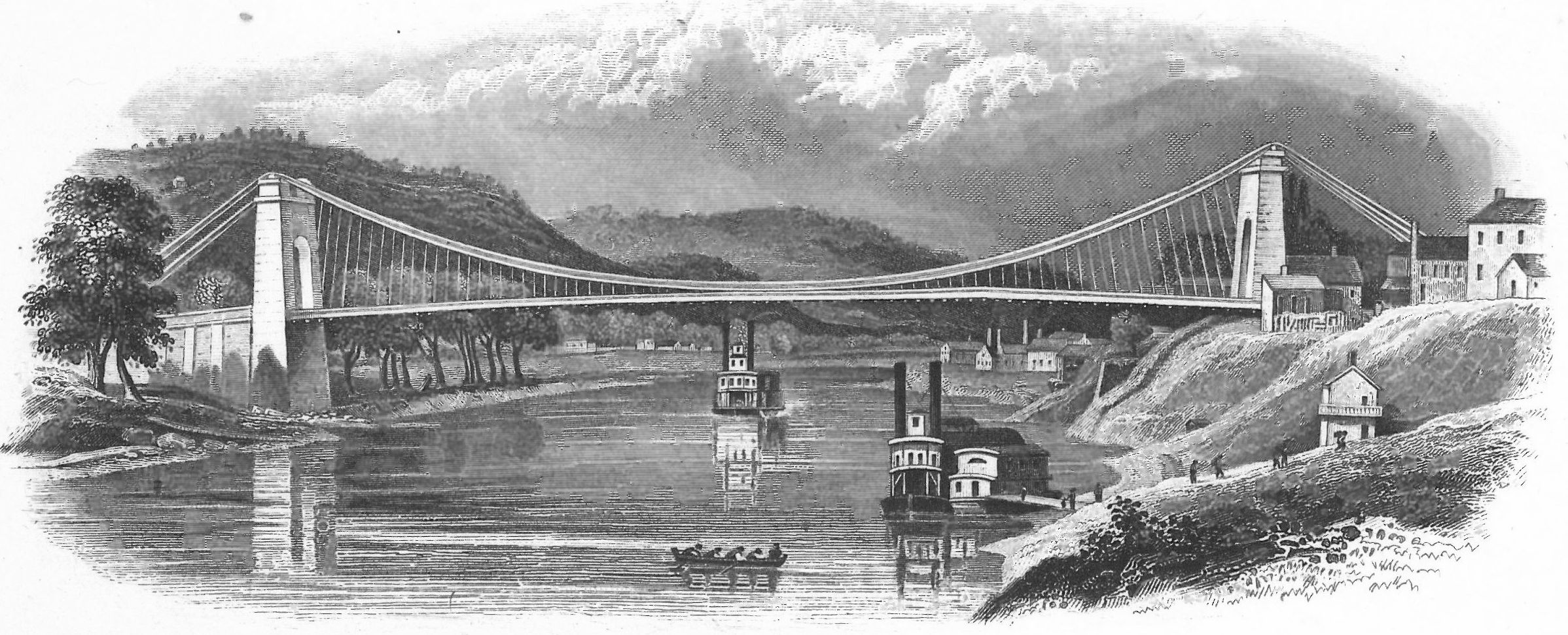

Leaving his young son in the care of his mother and sisters, Stanton moved to Pittsburgh in 1848, at the time a dark, dirty, brash, booming industrial center. Stanton’s most famous case from this period was the Wheeling bridge case, in which he argued that the Wheeling bridge was an unlawful impediment to interstate commerce, to the steamboat traffic on the Ohio River, because the tallest steamboats could not pass under the bridge at high water.

The case went on for a decade, back and forth among different courts, including several trips to Washington, to argue in the Supreme Court. There was also a political battle, in which the bridge company secured a statute from Congress declaring the road across the bridge a postal road, and then claimed this protected the bridge from Stanton’s efforts to have it removed or raised. At one point the bridge blew down in a storm, leading to questions about whether and how it could be rebuilt. The bridge Stanton wanted to see removed is still standing there, a national historic landmark, but in another sense Stanton won, for steamboat traffic continued, and Pittsburgh did not (as some had feared) lose its status as the regional center to Wheeling.

Not long after he moved to Pittsburgh, Stanton met Ellen Hutchison, daughter of a prominent Pittsburgh merchant. Some of the love letters that Edwin wrote to Ellen, in the months before their marriage, are in the National Archives in Washington. In December 1854, he wrote to Ellen from Washington describing a dinner party. “It was chiefly a gentleman’s party, and they are excessively stupid generally. While ladies are present the conversation is usually upon general or interesting topics but after their departure wine and segars, drinking, eating and political topics neither elevating or refining in their tendency ensue. I would never attend such assemblages if it could be avoided. I cannot but contrast the sensations produced by such associations with the feelings after spending the same length of time with a cultivated and refined woman like yourself dear Ellen.”

In September 1855, Stanton went to Cincinnati, to be part of a legal team in a patent case that included Abraham Lincoln. Stanton was supposedly rude to the future President, at this their first meeting, but there is no trace of that in these letters, or in other contemporary sources, only in memoirs written years later, by people who were not there. So although Stanton was often impolite, it’s not certain he was rude to Lincoln when they first met.

In June 1856, on the morning of the day they would wed, Stanton wrote to Ellen: “I salute you with assurances of deep and devoted love, that this evening will be attested by solemn vow before the world and in the presence of God. With calm and joyful hope, disturbed by no conflicting feeling, quiet and peaceful, I await the happy hour that shall witness our Union—to be thereafter parted no more until death part us, living only for each other; you a true and loving wife to me, I a true and devoted husband to you.”

The Stantons moved to Washington in late 1856, and he became an informal member of the Buchanan administration, doing legal work for the Attorney General, Jeremiah Black. At Black’s request, Stanton went to California for a year, to represent the federal government in major land cases, including one in which half of San Francisco was in dispute. Stanton loved California; he just did not like the people who lived there. “With all its advantages of climate, soil and minerals,” Stanton wrote home in one letter, “California is heavily cursed with the bad passions of bad men and I would not like to make my permanent abode upon its soil.”

In another letter he wrote to Black that when “California becomes settled with a new race of people and all the thieves, forgers, perjurers, and murderers that have invested it beyond any spot on earth shall be driven off, the coast will breed a race of men that have had no equal for physical & intellectual capacity.” One of the murderers whom Stanton had in mind was my ancestor, Clancey John Dempster, leader of the 1856 vigilance committee which had “tried” and hanged several men for alleged murder. Easterners like Stanton viewed the vigilantes as mere murderers.

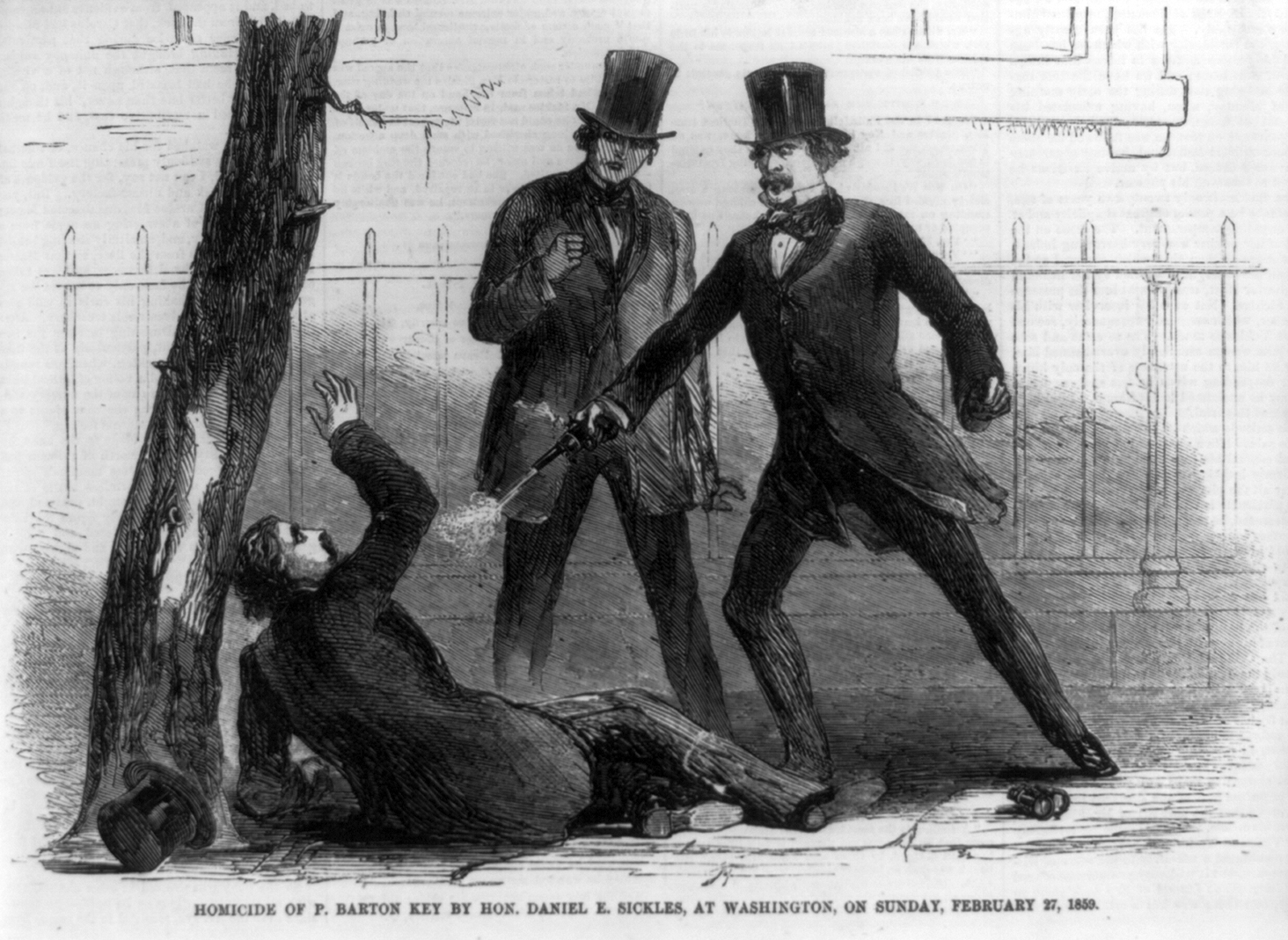

After he returned to Washington in early 1859, Stanton was part of the defense team for Daniel Sickles, a member of Congress, accused of murdering Philip Barton Key, in broad daylight in Lafayette Square. There was no question that Sickles had shot and killed Key; there were dozens of witnesses. But Sickles had a good reason to kill Key, who was sleeping with the young wife of Sickles, and the jury acquitted the Congressman, in part because of Stanton’s passionate plea that they should “defend the family” and exonerate Sickles.

In 1860, just after the election of Lincoln, as the southern states were seceding, Buchanan brought Stanton into his cabinet as Attorney General. Stanton was part of the debate over whether Buchanan should yield up Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, as the southerners and their northern allies demanded. Stanton insisted that Buchanan could not yield up Fort Sumter; to do so, Stanton told Buchanan, would be treason, making Buchanan just as bad as Benedict Arnold.

When Lincoln became president, in March 1861, Stanton returned to his private legal practice here in Washington. In private letters, Stanton was quite critical of the way in which Lincoln was handling the first few months of the war. He wrote that there was “no sign of any intelligent understanding by Lincoln, or the crew that groom him, of the state of the country, or the exigencies of the times. Bluster & bravura alternate with timidity & despair—recklessness and hopelessness by turns rule the hour. What but disgrace & disaster can happen?”

Lincoln probably heard rumors about Stanton’s comments and yet, in early 1862, when he needed to replace his Secretary of War, the disorganized and corrupt Simon Cameron, Lincoln turned to Stanton. Why? Partly politics; by appointing a leading Democrat Lincoln made it clear that this was a Union war, not just a Republican fight. Partly for personal reasons; Lincoln didn’t know Stanton well but some of his friends and advisers (including Seward and Chase) knew and praised Stanton. Partly Stanton’s reputation; he had a reputation for energy, efficiency, diligence, determination.

Stanton soon proved that his reputation was right. Within weeks of his appointment, for example, he had secured federal legislation to authorize the president to take control of the nation’s rail and telegraph systems. In theory Lincoln could have nationalized the railroads and telegraphs, seized them from their private owners, and compensated them only after the war’s end.

Instead, Stanton summoned the rail leaders to Washington, told them that he would work with them, but only if they would work closely with the War Department, and charge reasonable (read very low) rates. Stanton moved the Washington hub of the telegraph lines to his own office, so that served as the central command post for Lincoln and Stanton during the war.

A prime example of how Stanton used the rails and telegraphs during the war was his movement of troops in Tennessee in the fall of 1863. When it looked like the South would capture Chattanooga, along with thirty thousand northern troops there under General William Rosecrans, Stanton summoned Lincoln and others to the War Department for a midnight meeting. Stanton proposed to transfer 20,000 troops in a week’s time from northern Virginia to southern Tennessee. Lincoln laughed; he said that it would take at least a week’s time to transfer the troops the thirty miles from northern Virginia into Washington.

Stanton insisted the situation was “too serious for jokes.” Stanton persuaded Lincoln, then Stanton spent the remainder of the night, and the next few nights, in his telegraph office, sending and receiving messages. It was an incredibly complex, nearly impossible task, involving half a dozen different rail companies and several rail widths, two crossings of the Ohio river, which was not bridged at the relevant points, and erratic, imperfect telegraph communication. Stanton managed; the troops reached Chattanooga in a week; they not only saved the city but enabled Grant (soon placed in command) to advance from there.

Researchers can read the story of the rail movement in original documents in the National Archives. Stanton kept a complete set of every telegram that arrived in, and every telegram that was sent from, his war department telegraph office. Some but not all of these telegrams are printed in the Official Records; there are many interesting messages that can only be seen on National Archives microfilm. For the week of the rail movement, there are hundreds of messages, such as a request by Stanton that an aide at the Washington railroad station provide him with hourly reports regarding the troops arriving from northern Virginia and departing on the Baltimore & Ohio railroad heading west.

There are many other examples of Stanton the efficient, Stanton the diligent, but also Stanton the “arbitrary, capricious, tyrannical, vindictive, hateful, and cruel.” Not long after Stanton became secretary of war he heard complaints from members of Congress about General Charles Stone, a distinguished graduate of West Point with a long Army record. They claimed that Stone had inappropriate communications with rebel generals; they accused him as well of returning fugitive slaves to their Maryland masters. Stanton arranged for Stone to be arrested, for him to be transported to Fort Lafayette, kept in solitary confinement. Stanton leaked to the newspapers the “charges” against Stone but, in spite of repeated requests from Stone, Stanton never presented formal charges to a military court martial. Stanton kept Stone in prison for half a year and, when Congress finally forced Stanton to release Stone, Stanton denied Stone the chance to redeem himself on the battlefield.

Dennis Mahoney is another example of Stanton the tyrant. Mahoney was the editor of an anti-administration paper in Dubuque, Iowa. When Stanton issued an order, in the summer of 1862, authorizing the arrest of those who were “discouraging volunteer enlistments” Mahoney was among those arrested. The Democrats of his district responded by naming Mahoney as their candidate for Congress; Stanton’s response was to leave Mahoney in jail until after the election. In the next year, Mahoney published a book on his prison experience, and he dedicated the book to Stanton, saying Stanton had earned the distinction by his “acts of outrage, tyranny and despotism.”

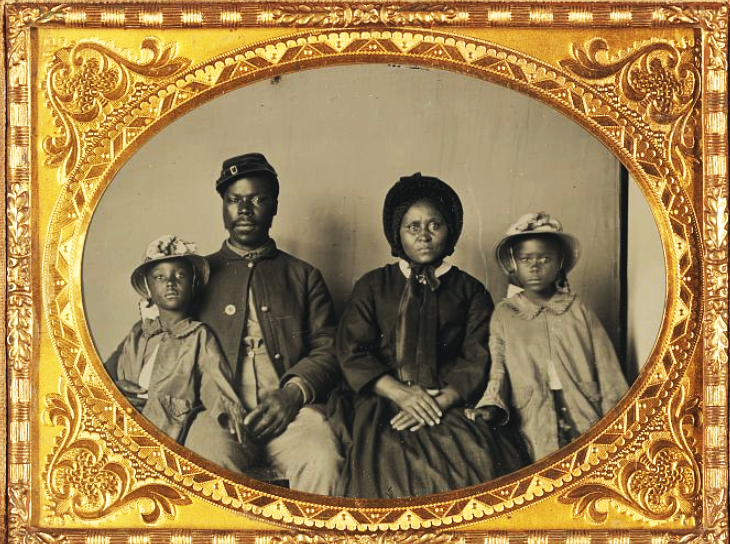

Stanton was an early advocate for an emancipation proclamation. Stanton was also concerned about the former slaves who crowded around the Union Army camps; he wanted to put the slaves to work, ideally putting the men into uniform as Union soldiers. Stanton wanted black soldiers not just because he needed more soldiers; Stanton understood the ways in which serving in the Union Army would change the lives of the former slaves. Stanton also pressed Congress for legislation, ultimately passed in early 1865, to create within the War Department a Freedmen’s Bureau, to look after the black women and children. For Stanton this was a moral issue; the federal government could not just free the slaves and leave them on their own to cope, without resources and without education.

What was Stanton’s relationship with Lincoln? In some senses they were similar: both from the Midwest, both lawyers, both political leaders, both opposed to slavery. In some sense they were very different: Lincoln always ready to listen, always ready to tell a story; Stanton always impatient, often rude. There is a scene in Spielberg’s Lincoln movie that captures this well; Lincoln and Stanton are in the telegraph room, and Lincoln is reminded of a story. Stanton blurts out: “you’re going to tell one of your stories! I can’t stand to hear another one of your stories!” And Stanton storms off to deal with a report, while Lincoln settles down to tell a rather risqué story.

But the two men worked extraordinarily well together. There was frequently pressure on Lincoln to remove Stanton, starting only weeks after he appointed the War Secretary, but Lincoln never considered it because he knew and valued Stanton’s work. Lincoln’s secretary John Hay put it well in a letter to Stanton not long after Lincoln’s death. “Not everyone knows, as I do, how close you stood to our lost leader, how he loved you and trusted you, and how vain were all efforts to shake that trust and confidence, not lightly given and never withdrawn.”

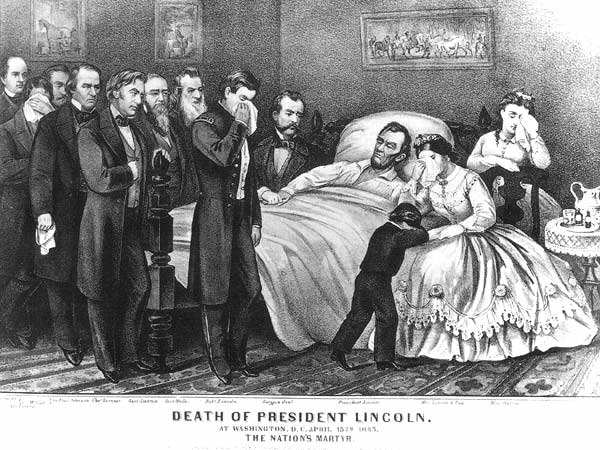

At about ten o’clock on the night of April 14, 1865, Stanton learned that John Wilkes Booth had shot Abraham Lincoln and almost simultaneously an assailant had attacked with a knife Secretary of State William Henry Seward and others in the Seward household.

Stanton rushed to Seward’s house, where he saw the blood-stained but surviving Seward, and the other victims, six in all in the house soaked in blood. Stanton then went, over the protests of his advisers, to the Petersen House, on Tenth Street, to which soldiers had borne the dying Lincoln. Stanton did not linger with Lincoln and the doctors; he went into the next room and went to work. He summoned and questioned witnesses, attempting to identify the assassins and their accomplices. He sent orders to arrest those suspected, and those who might have useful information. And he sent out a series of messages, press releases really, to inform the nation about the attacks, the condition of Lincoln and Seward, the early results of the investigation.

Early the next morning, just after Lincoln died, Stanton supposedly said “Now he belongs to the ages.” I say “supposedly” because the first time those words appeared in print was twenty-five years later, when Lincoln’s secretaries John Hay and John Nicholas published in serial form their biography of Lincoln. Unfortunately, none of the accounts of Lincoln’s death published just after his death, none of the letters and news stories, mention Stanton saying anything right at that moment.

So I am compelled, sadly, to conclude that Stanton probably never said “now he belongs to the ages,” the only quote for which he appears in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

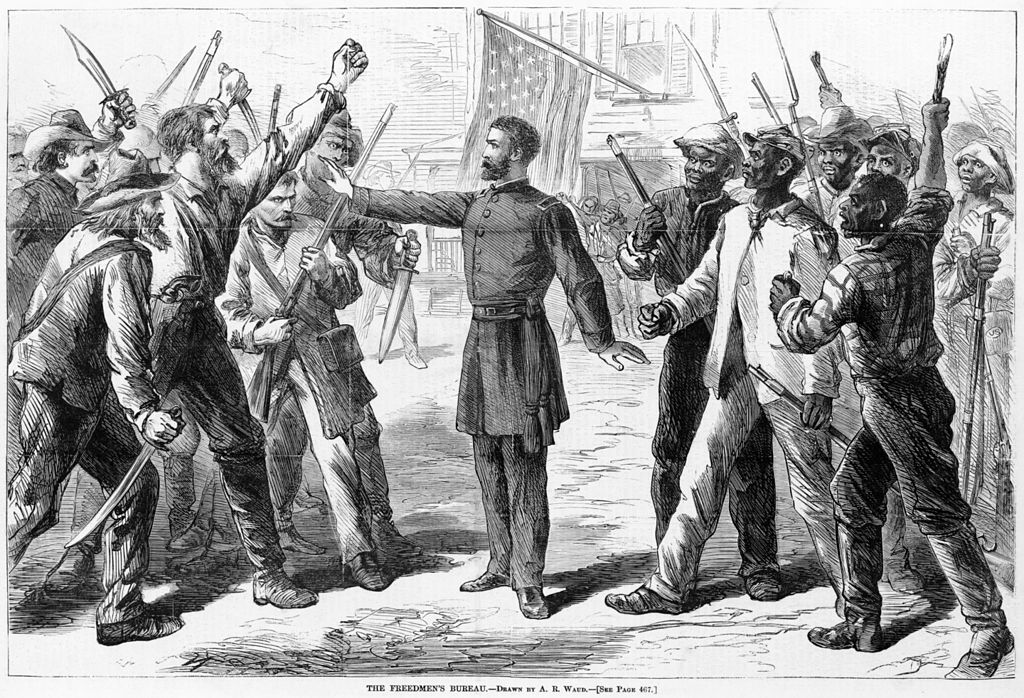

The new president, Andrew Johnson, and the carry-over Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, worked reasonably well together for the first few months. Indeed, it is remarkable to read the newspapers of late 1865 and early 1866, to see how popular Johnson was with almost everyone, North and South, Democrat and Republican. The first real break was in February 1866, when Johnson vetoed a bill to extend and strengthen the Freedmen’s Bureau. And then a few weeks later, Johnson vetoed a civil rights bill, arguing that the federal government had no role to play in civil rights, that these were purely questions for the states.

Johnson wanted to leave the government of the southern states to southerners, by which he meant of course white southerners. Also, Johnson wanted, as soon as possible, to remove the Union Army from the South.

Stanton disagreed; he saw the daily reports from the South, reports of southern blacks and northern sympathizers attacked and in some cases murdered by southern whites. Stanton knew that without the Union army, without the military courts, there would be no protection from such violence.

So Stanton insisted that the Union Army had to remain in the South, for years if necessary.

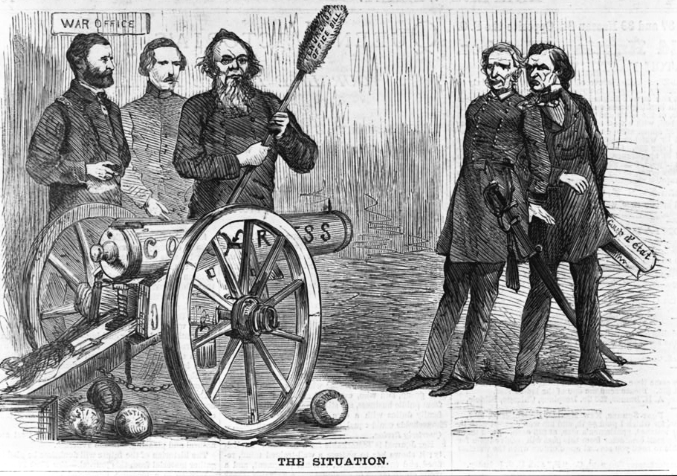

This was the key disagreement between Johnson and Stanton; and why Johnson wanted to remove Stanton from his position. But Congress complicated Johnson’s life by passing the Tenure of Office Act, which provided that the president generally needed Senate consent to remove an officer whose appointment required Senate approval. It was not quite clear whether this law applied to cabinet members, like Stanton, but finally Johnson was fed up, and in the spring of 1868, he informed Stanton that he was no longer secretary of war, that he should yield up his office to the new secretary, General Lorenzo Thomas.

Stanton refused, boarded himself up in the War Department and called upon his allies in Congress to impeach Johnson. The House impeached Johnson just a few days later, and the action then moved to the Senate, for the trial and possible removal of Johnson. This was the first but not the last time that the nation focused on the vague words of the Constitution; what exactly were “high crimes and misdemeanors” which would justify convicting a president and removing him from office? Johnson’s defenders argued that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional—a position with which most modern legal scholars agree—and that surely a president could not be convicted and removed for failing to follow an unconstitutional statute. Not only arguments but bribes were involved; Seward and others raised a large legal defense fund, relatively little of which was paid to Johnson’s lawyers; it now seems clear that several senators sold their votes. A majority of senators voted to convict, but not the required two-thirds majority, so Johnson survived, barely.

On the day of the final Senate vote, May 26, 1868, Stanton walked out of his office and, as best I can tell, he never again visited the War Department.

Stanton’s health was broken; he had suffered all his life from asthma and he now had progressive, congestive heart failure.

Stanton spent several weeks, in the fall of 1868, on the political campaign trail for Ulysses Grant, who was chosen president in that violent, vicious election. Stanton hoped and expected that Grant would find a suitable place for him, either again at the head of the War Department, or in the Supreme Court. Grant eventually named Stanton to the Supreme Court, in December 1869, but it was too late; Stanton died within days after the Senate confirmed his nomination. He was only fifty-five.