In this never-never land, the superhero is the gun slinger, the man who can draw fastest and shoot straightest.

-

August 1960

Volume11Issue5

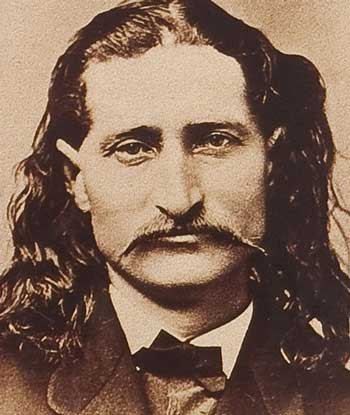

Wild Bill Hickok in an undated portrait.

The world of the Wild West is an odd world, internally consistent in its own cockeyed way, and complete with a history, an ethic, a language, wars, a geography, a code, and a costume. The history is compounded of lies, the ethic was based on evil, the language was composed largely of argot and cant, the wars were fought by gangs of greedy gunmen, the geography was elastic, and the code and costume were both designed to accommodate violence. Yet this sinful world is, by any test, the most popular ever to be described to an American audience.

Thousands of books have been written about it, many of them purporting to be history or biography all but a very few are fiction, and rubbish to boot. It has, of course, afforded wondrously rich pickings for the journeymen of the mass entertainments; scores of writers for pulp magazines, motion pictures, comic strips, radio, and television have hacked their way over its trails. Even artists of the first rank have drawn upon it. Mark Twain reported as fact some grisly rumors about one of it’s heroes; Aaron Copland composed the music for a ballet that glorified one of its most celebrated killers; Puccini wrote an opera about it; George Bernard Shaw confected an exceedingly silly play about it.

And it has not disappeared. It is still around, over thataway just a piece, bounded on three sides by credulity and on the fourth by the television screen. It will never disappear.

Any discussion of the conquest of the West may be likened to an animated gabble down the length of a long dinner table. At the head of it, where historians have gathered, the talk is thoughtful and focuses on events of weighty consequence. One man mentions the discovery of precious metals, which inspired adventurers by the scores of thousands. Another man tells of the Homestead Act of May, 1862, under the terms of which, within a generation, 350,000 hardy souls each carved a 160-acre farm out of raw prairie. A third speaks of the railroads that were a-building, four of them by 1884, to link the Mississippi Valley to the Pacific Coast. When it comes to the Indians, the historians all wag their heads dolefully, for they agree that the westward expansion came about only by virtue of treaties cynically violated and territory shamelessly seized.

The picture that emerges from their talk is one of grueling hard work; of explorers and trappers and bearded prospectors; of Chinese coolies toiling east and Irish immigrants toiling west, laying track across wilderness; of farmers with hands as hard as horn, sheltered from the blizzards and the northers only by sod huts; of ranchers and longhorn cattle and cowboys weary in the saddle. The quality evoked by their talk is of enduring courage, the greater because it is largely anonymous. The smell that hangs over their talk is of sweat.

But at the foot of the table, below the salt, where sit the chroniclers of the Wild West, the talk is shrill and excited, and the smell that hangs overhead is of gunpowder. For here the concern is with men of dash and derring-do, and the picture that emerges from the talk is of gaudy cowtowns and slambang mining camps: curious settlements in which the only structures are saloons, gambling hells, dance palaces, brothels, burlesque theaters, and jails; in which there are no people, but only heroes and villains, all made of pasteboard and buckram, all wearing sixguns, and all (except for the banker) with hearts of 22-carat gold.

In this never-never land, the superhero is the gun slinger, the man who can draw fastest and shoot straightest; in brief, the killer. Sometimes he swaggered along the wooden sidewalks with a silver star pinned to his shirt, a sheriff or a United States marshal, but whether he was outlaw or officer of the law, if he applied himself diligently to the smashing of the Ten Commandments, with special attention to the Sixth—that is, if he was a sufficiently ugly, evil, and murderous killer—he was in a way to become a storied American hero.

•

We propose to trundle five of these paragons- Billy the Kid and Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok, Bat Masterson, and Wyatt Earp—up for inspection at close range. Nor will the ladies be ignored: we will ask Calamity Jane and Belle Starr, the Bandit Queen, to curtsy briefly. But before entering this gallery of Papier-Mâché Horribles, we may find it instructive to reflect upon the technique by which an uproariously bad man can acquire a reputation at once inflated, grisly, and prettified. This will require some small knowledge of the economics of the Wild West and a brief peek at the sources available to the chroniclers of this hazy world, this world so clouded by the black gunsmoke of all those Navy Colt .45’s.

There were, broadly speaking, two ways of making money in the Wild West. One, as has been suggested, demanded hard, hard work of farmer, cowhand, railroader, or miner. But as always seems to be the case in this bad old world, there were some few men who did not care for hard work. Either they had tried it personally, for a day or two, and found it repugnant, or they had conceived a distaste for it by watching others try it, or perhaps they had simply heard about others who had tried it and so come to a bad end. In any case, these men determined never to work but to rely, rather, on their wits.

Now how could a quick-witted man get rich out on the bare, bleak plains? Clearly the first step was to head for those outposts of civilization, however malodorous to a discriminating rogue, where a little heap of wealth had been piled up through the labor of others. This meant the cowtowns, the mining camps, and the slowly shifting railroad settlements. Here he could gamble with the chumps: few professional gamblers starve. Here he could trade on women of easy virtue, or no virtue whatever, who were in even greater demand west of the Mississippi than east of it. Here he could buy a share of a dance hall or saloon: either enterprise was gilt-edged. Before long he would have found, as others have before and since, that these careers lead straight into politics. He might have concluded that it was cheaper to stand for office himself than to pay tribute to some stupider, lazier politician. So were marshals and sheriffs born.

But what of the dull-witted man who didn’t choose to work? He had behind him a life of violence bred by the Civil War; often his thick skull held no learning whatever save how to ride, shoot, kill, burn, rob, rape, and run. With the end of the war he doffed his blue blouse—or, more often, his gray—and headed west toward a short, gory life of bank heists and train robberies. So were outlaws born.

For the man who was preternaturally active and had no objection to a day in the outdoors, there was a third, coarsening, semi-legal path to quick dollars: he could slaughter bison. Only the Indians would object, and who cared a hoot for the Indians? A treaty of 1867 guaranteed that no white man would hunt buffalo south of the Arkansas River; by 1870, when the army officer commanding at Fort Dodge was asked what he would do if this promise were broken, he laughed and said, “Boys, if I were hunting buffalo I would go where buffalo are"; in 1871 the massacre began in earnest. One hunter bagged 5,855 in two months. It has been estimated that 4,373,730 bison were killed in the three years 1872-74. To shoot the placid beasts was no easier than shooting fish in a barrel, but it was certainly no more difficult. And splendid practice, as safe as on a target range, for the marksman who might later choose to pot riskier game—a stagecoach driver or the leader of a posse. So were killers trained.

For the purposes of American myth, it remained only to make over all these sheriffs, outlaws, killers, and assorted villains into heroes. Considering the material on hand to work with, this transfiguration is on the order of a major miracle. It was brought about in two ways. First, whilst the assorted plug-uglies were still alive, hosannas were raised in their honor (a) by the “National Police Gazette,” a lively weekly edited from 1877 to T922 by Richard K. Fox and commanding a circulation that reached into every selfrespecting barbershop, billiard parlor, barroom, and bagnio throughout the Republic ; and (b) by each impressionable journalist, from the more genteel eastern magazines, who had wangled enough expense money out of his publisher to waft him west of Wichita. Fox required no authentication and desired none ; his staff writers simply pitched their stuff out by the forkful, to be engorged by yokels from Fifth Avenue to Homer’s Corners. The aforesaid round-eyed journalists, on the other hand, got their stuff straight from the gun fighters themselves, so naturally it was deemed wholly reliable.

Second, after the assorted plug-uglies had been gathered to their everlasting sleep, the latter-day chroniclers crept eagerly in. They (or at least a few of them) would be careful and scholarly; they would write nothing that was not verified either by a contemporary newspaper account or by an oldtimer who knew whereof he spoke from personal knowledge. Thus, whatever they printed would be the truth, the whole truth, &c.

One flaw in this admirable approach was that the contemporary newspaper accounts are not reliable. How could they be, when the newspapers themselves were flaring examples of the sort of personal journalism in which bias as to local politics and personalities customarily displaced respect for facts? Any halfway independent and intelligent reporter for the newspapers of the Wild West knew that, when he wrote about the gunmen of his community, he was describing an interconnected underworld, a brotherhood that embraced outlaw, politician, and sheriff quite as amicably as does the brotherhood of gangster and corrupt official in the cities of our own time. Such an insight normally flavored his copy.

•

The other flaw was that the stories of oldtimers came not from personal knowledge of what happened so much as from the files of the imaginative “National Police Gazette.” Venerable nesters could be found all over the Southwest, fifty years after the timely deaths of Billy the Kid or Jesse James or Belle Starr, clamoring to testify to the boyish charm of the one, the selfless nobility of the other, and the amorous exploits of the third. Their memories were all faithful transcripts of the “Gazette’s” nonsense. Its editor’s classic formula for manufacturing heroes had so effectively retted the minds of his readers that they could never thereafter disentangle fiction from fact.

Analysis of this Fox formula for heroes reveals that it has ten ingredients, like a Chinese soup :

- (1) The hero’s accuracy with any weapon is prodigious.

- (2) He is a nonpareil of bravery and courage.

- (3) He is courteous to all women, regardless of rank, station, age, or physical charm.

- (4) He is gentle, modest, and unassuming.

- (5) He is handsome, sometimes even pretty, so that he seems even feminine in appearance; but withal he is of course very masculine, and exceedingly attractive to women.

- (6) He is blue-eyed. His piercing blue eyes turn gray as steel when he is aroused ; his associates would have been well advised to keep a color chart handy, so that they might have dived for a storm cellar when the blue turned to tattletale gray.

- (7) He was driven to a life of outlawry and crime by having quite properly defended a loved one from an intolerable affront—with lethal consequences. Thereafter, however,

- (8) He shields the widow and orphan, robbing only the banker or railroad monopolist.

- (9) His death comes about by means of betrayal or treachery, but

- (10) It is rarely a conclusive death, since he keeps on bobbing up later on, in other places, for many years. It is, indeed, arguable whether he is dead yet.

With these attributes in mind let us gather around the first exhibit—a man narrow-waisted and widehipped, with small hands and feet, whose long curly hair tumbles to his shoulders—in sum, a man who looks like a male impersonator. His label reads

James Butler (Wild Bill) Hickok was born on a farm in La Salle County, Illinois, on May 27, 1837. He died on the afternoon of August 2, 1876, in Saloon No. io, on the main street of Deadwood, in the Dakota Territory, when a bullet fired by Jack McCaIl plowed through the back of his head, coming out through his cheek and smashing a bone in the left forearm of a Captain Massey, a river-boat pilot with whom Hickok had been playing poker. During his lifetime Hickok did some remarkable deeds, and they were even more remarkably embroidered by himself and by a corps of admiring tagtails and tufthunters. When he died, he held two pair—aces and eights—a legendary combination known ever since as “the dead man’s hand.” It is the least of the legends that has encrusted his reputation, like barnacles on an old hulk.

Was he brave? His most critical biographer, William E. Connelley, has said that fear “was simply a quality he lacked.”

Was he handsome? He was “the handsomest man west of the Mississippi. His eyes were blue—but could freeze to a cruel steel-gray at threat of evil or danger.”

Was he gallant? His morals were “much the same as those of Achilles, King David, Lancelot, and Chevalier Bayard, though his amours were hardly as frequent as David’s or as inexcusable as Lancelot’s.”

Had he no minor vices? Very few: “Wild Bill found relaxation and enjoyment in cards but he seldom drank.”

Could he shoot? Once in Solomon, Kansas, a pair of murderers fled from him. “One was running up the street and the other down the street in the opposite direction. Bill fired at both men simultaneously and killed them both.” Presumably with his eyes closed. Again, in Topeka, in 1870, Buffalo Bill Cody threw his hat into the air as a target. “Wild Bill shot an evenly spaced row of holes along the outside of the rim as it was falling, and before it touched the ground.” To appreciate fully this miracle of marksmanship, one must remember that Hickok was shooting black-powder cartridges. (Smokeless powder did not come into general use until about 1893.) Each time he fired, therefore, he put a puff of black smoke between himself and his target. After his first shot, he could not have seen his target. But then, nothing is impossible to the gun slinger of the Wild West.

But surely he was modest? Yes, indeed. “Faced with admirers, he blushed and stammered and fled.”

Was he a sure-enough killer? Once he was asked how many white men he had killed, to his certain knowledge (Indians didn’t count). Wild Bill reflected. “I suppose,” he said at last, “I have killed considerably over a hundred.” But this was in 1866: he would have another ten years to improve his record. To another reporter, he remarked: “As to killing men, I never think much about it. … The killing of a bad man shouldn’t trouble one any more than killing a rat or an ugly cat or a vicious dog.” Of course, it helps if one is as good a judge as Hickok of the badness of a man, or the ugliness of a cat.

But was a good man not obliged to kill a bad man, to tame the Wild West? And, after all, was Wild Bill not a pillar of righteousness in those sinful times? What about his lustrous reputation as marshal of the Kansas cowtowns?

Hickok was, perhaps, a United States deputy marshal operating out of Fort Riley in February, 1866, and charged with rounding up deserters and horse thieves ; but the record of his tenure is fuzzy.

In mid-August, 1869, he was elected sheriff of EHs County—of which Hays was the biggest town —to fill an unexpired term. He failed of re-election in November. A brief time in which to tame a tough town—nor does the record show any notable success. He may have killed a man named Jack (or Sam) Strawhorn (or Strawhan) who tried to get the drop on him ; he may have killed two soldiers who talked tough at him; he may have thrashed Tom Custer, a brother of General George Custer; he may have killed three soldiers whom Custer had vengefully sicked on him—all the evidence bearing on these matters is likewise fuzzy. What is certain is that Hickok left Hays in a hurry one winter night, lest he be further beset by the Seventh Cavalry.

In April, 1871, Hickok was appointed marshal of Abilene, and now the picture grows sharper. It was an auspicious conjunction of man and town: each was at the height of notoriety. As for the town, which was all of five years old, 1871 would be its peak year as a cowtown; 600,000 cattle would pass through its yards on the way to eastern markets ; and all summer, cowboys by the hundreds would jam its saloons and dance halls—the Alamo, the Bull’s Head, the Mint, and the Gold Room—to squander a year’s wages. As for the man, “Harper’s Monthly” had published not long before a lurid account of Hickok’s fatal skill in battle, as told to George Ward Nichols by Wild Bill himself. There was, for instance, Hickok’s version of the McCanles affair. In truth, Hickok had shot down Dave McCanles from behind a curtain, shot a second man from behind a door, and mortally wounded a third man who was running for his life. But as Wild Bill told the tale to the bug-eyed Nichols, he had been attacked by McCanles and a gang of nine “desperadoes, horsethieves, murderers, regular cut-throats,” but had slain six men with six shots and dispatched the other four “blood-thirsty devils” with his knife.

A man whose fame rested on such fabulous fibs was just the sort needed to quell the frequent riots of a wicked cowtown. At least, so thought Joseph McCoy, the founder of Abilene and, in 1871, also the town’s mayor. Moreover, McCoy knew where to find his man, for Hickok was right in town, gambling for a living at the Alamo. Wild Bill took the job. He slung two six-guns at his hips; he thrust a knife in the red sash he affected. In this fashion, he occasionally patrolled the streets.

But only occasionally. Most hours of most evenings he could be found at the Alamo, gambling with the cowboys. Most hours of most nights he had business in Abilene’s red-light district. Meantime the taxpayers of Abilene chafed. Nor were the cowboys happy; for they were persuaded that Hickok wore the star only to protect the extortions of the professional gamblers, madames, and saloonkeepers.

Matters came to a head on the night of October 5. A bunch of cowboys had been hurrahing the town in their traditional and tiresome fashion—forcing merchants of clothing to outfit poorly clad strangers, obliging passers-by to stand drinks for all hands- and Hickok reportedly warned them to quiet down. Back in the Alamo at his poker table, Wild Bill heard someone fire a shot. He plunged out into the darkness to confront a Texan named Phil Coe. Some say that Coe’s gun was already back in its holster, some that it was dangling in his hand. Whichever the case, Hickok fired, felling Coe, and then, when he heard someone running toward him, at once wheeled and plugged his own deputy, one Mike Williams, in a typical exhibition of coolness, calm, and nerve. He was relieved of his official duties six weeks later.

After that there was nothing left but to exploit his celebrity in show business. He joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s stock company, an ignoble enterprise, but quit before long. In June, 1876, a Kansas newspaper reported, from Fort Laramie, that Wild Bill “was arrested on several occasions as a vagrant, having no visible means of support.”

Later that month he galloped into Deadwood with a retinue that included, of all people, Calamity Jane. He settled down to gambling, as was his wont ; she to drinking, as was hers. A little more than a month later Jack McCaIl shot him from behind, for no particular reason.

Hickok had been a brave army scout and an able Indian scout ; he had also been a liar, a frequenter of bawdy houses, a professional gambler, and a killer. His score, according to a conservative chronicler of his deeds, was thirty-six men killed, apart from his service in the Army and against the Indians. What more fitting, for such a man, than to enshrine him on television, during the children’s hour?

There is a tale that tells of how Calamity Jane, furious when she hears of Wild Bill’s death, pursues his killer and corners him in a butcher shop, where she has to be restrained from splitting his brisket with a cleaver. Alas ! not true. There is another tale that tells of how Calamity, on her deathbed years later, whispers, “What’s the date?” When she is told it is August 2, she smiles and murmurs, “It’s the twenty-seventh anniversary of Bill’s death.” Then, while the violins sob a little in the background, she adds, “Bury me next to Bill.” This is likewise horsefeathers. (She died on August i, 1903.) Yet the legends persist in linking the two together.

Were they lovers? Wild Bill’s adherents flatly deny it, claiming that their man was far too fastidious. What their denial lacks in gallantry, it makes up in logic. Calamity was the most celebrated female of the Wild West, but she was no rose.

She may have been born in 1852, in Missouri (or Illinois); her name may have been Mary Jane Canary (or Conarray). Her mother may have been a prostitute, and later a madame in Blackfoot, Montana, around 1866, managing a house that may have been called the Bird Cage. Notable citizens of the Wild West share an irritating nebulosity when it comes to recorded data.

There are seven different theories as to how she came by her name, none of them plausible enough to concern us here. This much is certain : Calamity Jane loved the company of men and, as time went on, she craved booze more and more.

Assuming that she was born in 1852, she was thirteen when she bobbed up in Montana, conjecturally an orphan; seventeen when, wearing men’s clothes, she was consorting with the railroad section gangs in Piedmont and Cheyenne, Wyoming; twenty when, in Dodge City, she made a cowboy crooner called Darling Bob Mackay dance tenderfoot (i.e., obliged him to scamper about by firing bullets at his feet) because he had said something indelicate about her underwear ; twenty-three, and the only female member, when she joined a geological expedition into the Black Hills ; and twentyfour when, the only woman amongst 1,500 men, she left Fort Laramie with a bull train hauling supplies for General Crook’s expedition against the Sioux.

Not long after, a scandalized colonel caught her swimming naked with some of her buddies in Hat Creek, near Sheridan, and promptly banished her. Undaunted, she got Grouard, Crook’s chief of scouts, to appoint her an Indian scout under his command —or so it was said, but never proved.

By then the unfortunate woman was a seriously sick alcoholic, ready for any man’s exploitation if only she could get a drink. Greedy showmen hired her for appearances in dime museums; her ghostwritten memoirs appeared, published in a cheap pamphlet, and Calamity took to hawking copies for whatever she could get.

And then, long after Calamity was dead, a woman appeared who produced a paper certifying the marriage on September 1, 1870, of Martha Jane Cannary and James Butler Hickok ; she claimed to be the daughter of Wild Bill and Calamity Jane. She claimed it right out loud, to an audience of several million persons, over a network of radio stations. But presently the document was characterized as a forgery by experts, and the chroniclers of the Wild West could return to their speculations.

And here let us leave Calamity and Bill.

For we have come to our second Horrible—a slope-shouldered man whose blue eyes blink incessantly (he has granulated eyelids), and whose short whiskers grow dark on his chin and lower lip. We are now in the presence of the bandit-hero. He is

Any study of Jesse Woodson James (September 5, 1847-April 3, 1882)—the celebrated Missouri ruffian, murderer, bank robber, train robber, and American demigod—is best prefaced by a quick glimpse at his mother, Zerelda E. Cole James Simms Samuel. She was, by all accounts, a notable woman.

After attending a Roman Catholic convent school in Lexington, Kentucky, she married a Baptist seminarian, Robert James. He left her to seek gold in California, where he died. Her second husband, Simms, having died as she was about to divorce him, she married a third, “a meek man.” “She was, all her life, a religious woman,” says one of Jesse’s admiring biographers. “Love became her religion,” says another. “She was a woman thoroughly good and noble,” the first biographer insists. Most certainly, the second agrees; and then informs us that, after her notorious son had been killed, she “boldly” showed tourists around Jesse’s old farm, “extracting every dime she could from them.” “This woman who had always been so upright,” he adds, sold the tourists stones allegedly from Jesse’s grave but actually from the creek. She also sold tourists enough shoes from the horses her two bandit sons had ridden “to fill a wagonbed.”

But hear her cry out at Jesse’s funeral, while two ministers lead the mourners in singing “We Will Wait Till Jesus Comes.”∗“Oh, my generous, noblehearted Jesse,” she moans, clearly enough to be heard by the reporters attending. “Oh, why did they kill my poor boy who never wronged anybody, but helped them and fed them with the bread that should go to his orphans?”

∗Or, as it may have been, ”What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” As seems always to be the case in these histories of Wild West personages, the authorities cannot agree on anything, no matter how grave of import.

Her poor, generous, noble-hearted boy, who never wronged anybody, was the leader of a gang of comparably generous, noble-hearted thugs who, in fifteen years, held up eleven banks, seven trains, three stages, one county fair, and one payroll messenger, in the process looting some $200,000 and killing at least sixteen men. What the mothers of these sixteen said at their graves has unfortunately not been recorded.

Jesse’s deification proceeded along the routine lines laid down by the “Police Gazette”—his prankish charm, his courteous behavior to women involved in his stick-ups, his protection of fictitious’ widows from villainous bankers seeking to foreclose fictitious mortgages, and all the rest—but in his case a unique attribute was added, one guaranteed to inflame the partisan passions bred of the Civil War. For Jesse symbolized the gallant Rebel, ground down beneath the boot of the victorious Yankee oppressor, and such was the potency of this bogus magic that his death kept the sovereign state of Missouri in an uproar for an entire decade.

Jesse grew up in an atmosphere of hate. Missouri men rode across the line into Kansas to cast fraudulent votes they hoped would make Kansas a slave state; Kansas men resisted; Missouri men rode again to raid and kill ; Kansas men rode back in vengeance. When the Civil War erupted, there was a whole generation of teen-age toughs living in the tier of Missouri counties that border on Kansas, all of them handy with guns and knives, all of them committed on the political issues of the day, all of them itching to start a rumble. To name just a handful of these hellions: there were Frank James, eighteen, and his brother Jesse, fourteen; Cole Younger, seventeen, Jim Younger, thirteen, and two other brothers, Bob and John, who were still just children; Jim Reed, sixteen; Ed Shirley, about eighteen, and his sister Myra Belle, thirteen.

All these youngters (except Myra Belle) became bushwhackers—i.e., Confederate irregulars—most of them serving under the infamous William C. Quantrill, the psychopathic turncoat and killer who is justifiably remembered as “the bloodiest man known to the annals of America.” Frank James and Cole Younger were with Quantrill when, in August, 1863, the town of Lawrence, Kansas, was sacked and 182 of its citizens murdered. Jesse James and Jim Younger were with Quantrill’s lieutenant, Bloody Bill Anderson, at the Centralia massacre a year later, when more than two hundred Federal soldiers were shot down, many of them being prisoners. Jesse is credited with killing the commander, Major H. J. Johnson. Jesse was then seventeen.

With the end of the war, most of the bushwhackers laid down their guns and went to work as decent citizens. Not, however, this handful.

The James and Younger brothers (and probably Jim Reed) hitched together a gang of like-minded hooligans that went right on robbing and killing. Their first score, at Liberty, Missouri, on February 14, 1866, was against the Clay County Savings Association Bank, an institution where, it may be presumed, many of their friends and neighbors kept their money. Frank and Jesse missed this caper, but their henchmen stole a sum estimated at from $62,000 to $75,000; they killed one man. Why should they turn back after such a success?

In between robberies and murders, they occupied themselves variously. When Cole Younger, for example, hid out in Texas in 1868, who should he find down there near Dallas but li’l ole Myra Belle Shirley ! Why, the last time he saw Myra Belle, back in Jasper County, she was just a scrawny kid in pigtails ! But before long she was the mother of his illegitimate daughter, a girl she named Pearl Younger. And when Jim Reed came south in 1870, also on the lam, Myra Belle took him also into her house, and she cleaved unto him and presented him also with an illegitimate child, a boy she named Ed Reed. For his part, Jim Younger whiled away the time between robberies by serving as deputy sheriff in Dallas.

But the acknowledged leader of “The Boys,” as they were fondly called, had no use for such tom-foolery because, we are told, he was too pious. Jesse James was baptized and added to the strength of the Kearney Baptist Church near his home in 1868 (soon after he had killed a man in a bank robbery at Richmond, Missouri). He sang in church choirs; he even organized a group of the faithful and taught hymn-singing (a few months after murdering the cashier of a bank in Gallatin, Missouri). His Bible, we are assured, was well-thumbed ; but apparently he skipped the chapters in Exodus where are listed the Ten Commandments, for he continued to kill and to steal, and at least twice he did not remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy, but rather used it as the occasion for a train robbery.

By 1874 Jesse’s crimes were a chief issue in Missouri’s gubernatorial campaign: whether or not to suppress outlawry so that “capital and immigration can once again enter our state.” But nothing was done ; his raids continued.

By 1881 the baying was so close at Jesse’s heels that pious or no, he likewise took off for Myra Belle’s recherché resort for the criminally inclined. She had removed to a country place on the Canadian River in Oklahoma, which for nostalgic reasons she called Younger’s Bend. Belle, having by now given the boot to such sometime outlaw-lovers as Jack Spaniard, Jim French, Jim July, John Middleton, and an Indian known as Blue Duck, had actually gotten married to a Cherokee named Sam Starr. She was in consequence now known as Belle Starr, and could Jesse have known that she would one day be celebrated all over the country as the Bandit Queen, or the Female Jesse James, he might have cursed a tiny curse, pious man that he may have been notwithstanding. But he was dead before then, shot in the back of the head by “the dirty little coward,” Bob Ford.

Myra Belle Shirley, horse thief, cattle thief, suspected robber of stagecoaches, constant concubine and protector of desperate criminals, was shot in the back and killed near Eufaula, Oklahoma, on February 3, 1889. A neighbor, Edgar Watson, was accused of her murder, but the charges against him were dismissed. It was rumored that she was slain by her son, Ed Reed, with whom she had had incestuous relations. He was angry with his mother, for she had whipped him after he rode her favorite horse without her permission. So it went, out in the glamorous, romantic Wild West. Scarcely a day passed without some gay and gallant gun slinger shooting his way into the affections of future generations.

Her old neighbor Jesse James lies under a small stone near the site of the Kearney Baptist Church. The stone is all that has been left by souvenir hunters of what was once a pretentious monument, on which had been carved this inscription:

His mother and stepfather lie in graves on either side of his. On her stone is carved MOTHER, and on his is carved PAPPY.

But had Jesse really been killed in 1882? There were folk in Clay County—and elsewhere, too—who whispered that the murder had been staged, that Jesse still lived and would ride again. He “couldn’t” have died. The flood of dime novels about him, the plays, the six motion pictures contrived by Hollywood, this was not enough : the gullible still swore that Jesse lived. Naturally, this being the case, men claiming to be Jesse began to appear one after another. But at length time ran out on them. The last claimant bobbed up in 1948, which meant that he had to act 101 years old, an irksome role. This scalawag at least had the wit to take an appropriate alias. He asserted that he had lived through the years as Frank Dalton, a name which, since it recalled the Dalton gang of the 1890’s, fitly closed the circle of Wild West outlawry.

It is time to turn to our next exhibit. Here we have two men mounted on the same pedestal, standing shoulder to shoulder; pals, pards till hell freezes. Each is expressionless, poker-faced; each is clad in black broadcloth and white linen; each affects a handlebar moustache; each has hard blue-gray eyes; each wears a star; at each hip hangs a six-gun. Clearly we are now confronting the men who tamed the Wild West. Sure enough, for their labels read

Here are two of the regnant superheroes of the televised Wild West. Once upon a time they faced the same foes in the same filmed fables, but times have changed ; they have gone their separate sponsored ways. This is a pity, for in real life the two were thick as thieves.

Each week we are shown—in bland, bright little slices of televised entertainment—just how they scrubbed the Wild West clean, including the back of its neck and behind its ears. Clean-cut and cleanshaven, Wyatt romances Nellie Cashman, the “miners’ angel,” or he avenges the murder of some Indian friends, or he traps some mining executives who would thieve silver bullion. Elegant and cleanshaven, Bat foils a horse-race swindler, or he gallantly assists some ladies in their struggle for woman’s rights, or by examining the brushwork he perceives that some oil paintings are spurious. All this is only so much ingenious fretwork on the EarpMasterson legend, contrived by worthy successors to the staff writers of the “National Police Gazette.” But the legend is itself such an imposing structure as to require no further embellishment.

The legend tells us that Marshal Earp cleaned up two Kansas cowtowns, Ellsworth and Wichita, singlehanded. He then joined forces with Bat Masterson to clean up Dodge City, “the wickedest little city in America.” So much accomplished, Marshal Earp turned his attention to the featherweight task of pacifying Tombstone, Arizona, a hotbed of outlaws unparalleled in history, whilst Sheriff Masterson proceeded to stamp out sin in the mining camps of Colorado. Thereafter both men retired, breathing easily, having made the Wild West safe for the effete tenderfeet of the East.

Both men, the legend adds, were courteous to women, modest, handsome, and blue-eyed. We are also told that Earp was the Wild West’s speediest and deadliest gun fighter. For his part, Masterson disdained to pull a gun, preferring to clout an adversary senseless with his cane, whence his nickname. But he was quite willing to testify to his pal’s prowess and so contribute to the legend. Earp, so Masterson has assured us, could kill a coyote with his Colt .45 at four hundred yards.∗

∗Such skill calls for some respectful analysis. At foui hundred yards a coyote cannot be seen against his natural background, so we shall assume the animal is silhouetted against the sky. Even so. an expert using a rifle with a globe sight would congratulate himself if he hit such a target with any regularity, much more if he killed it. A pistol, of course, will not carry so far directly; the marksman must use Kentucky windage—i.e., he must aim appreciably above his target so that his bullet will carry. Masterson admitted that “luck figures largely in such shooting.” If. instead of “largely,” he had said “romplelclv.” lie wmikl have come closer to that coyote.

Masterson himself, who was in truth a poor shot, killed at most four men throughout his career (not counting Indians). Indeed, these two differ sharply from other Wild West heroes in that they rarely fired their six-guns in anger. They were both sly, cunning, cautious men, who early learned that shooting might reap a bloody harvest. In consequence, they walked warily, carrying a big bluff. In their time, the Wild West killer and outlaw was dying out, to be replaced by the confidence man. Confidence men rarely kill ; they are too artful. Both Earp and Masterson were, among other things, eager students of the technique of early confidence games.

They first met in 1872, when both were hunting buffalo on the Salt Fork of the Arkansas, in direct violation of the Indian treaty. Earp was twentyfour; Masterson was nineteen. They seem to have recognized that they were kindred souls, but they parted, not to come together again until the summer of 1876, in Dodge City. During those four years Bat was, so to say, preparing himself to be a peace officer. He stole forty ponies from some Indians and sold them for $1,200, he killed other Indians both as a free-lance buffalo hunter and as an army scout, and he got into a brawl with an army sergeant at Sweetwater, Texas, over a dance-hall girl. The girl was killed while trying to shield Masterson; Bat was wounded, but he killed the soldier.

Meantime Earp, by his own account, had engaged in even more impressive heroics. First there was his mettlesome exploit at Ellsworth in 1873. To hear him tell it, Earp stepped out of a crowd, unknown and unheralded, and stalked alone across that familiar sun-baked plaza to disarm an able and truculent gun fighter, the Texas gambler Ben Thompson. Not only that, but Thompson was backed up at the time by a hundred pugnacious cowboy friends. How could Earp ever have dared to do it? He would seem to have been cloaked in invisibility, for others who were present never saw him—not the reporter for the Ellsworth newspaper; not Thompson himself; not Deputy Sheriff Hogue, to whom Thompson voluntarily turned over his gun; and not Mayor

Earp’s trouble began on the night of March 15, 1881, when a stagecoach left Tombstone carrying eight passengers, and, we are told, $80,000 worth of bullion.∗ Bandits attempted to halt this miracle of transportation. They failed, but in the process they killed the driver and one passenger. The killer was, according to a statement by his wife, Doc Holliday; and the talk around town was that the brain behind the bungled holdup was Wyatt Earp’s. Moving fast, the Earps persuaded Big Nose Kate to retract her statement and bundled her out of town lest she contradict the retraction. There remained the task of silencing forever Holliday’s accomplices.

∗It is always instructive to examine Wild Western estimates. At $1 per fine ounce. $80,000 worth of bullion would weigh two and a hall ions, a load sure 10 snap the axles of any coach.

Wyatt went to one of their friends, Ike Clanton, and offered a deal. If Clanton would arrange to have those accomplices hold up another stage so that Earp and Holliday could ambush them, he, Earp, would guarantee that Clanton would be paid the reward for their capture. Clanton seems to have considered this offer seriously, but at length he refused. The rebuff was serious, for Ike was a blabbermouth who could not be trusted to keep the offer quiet.

Nor did he. Scared stiff that he would be shot for a stool pigeon, Clanton denied everything, so loudly and publicly that Doc Holliday overheard him and reported to Wyatt. That was in mid-October. Something would have to be done.

On October 26, Ike Clanton was back in Tombstone with his younger brother, Billy. With them were Frank and Tom McLowry and another youngster, Billy Claiborne. All these men were cattle rustlers or, at the very least, hard cases. That morning Virgil Earp, as town marshal, deputized his brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and thereafter the three prowled the streets, seeking to pick a quarrel with the Clantons or the McLowrys. Virgil Earp clubbed Ike Clanton with the barrel of his revolver. Wyatt Earp deliberately jostled Tom McLowry and then struck him. But despite the provocations, there was no fight.

That afternoon the Clanton brothers, the McLowry brothers, and Claiborne went to the O. K. Corral to pick up their horses and ride out of town. Wyatt, Virgil, and Morgan Earp, together with Doc Holliday, went after them. Sheriff John Behan tried to interfere, but he was brushed aside.

The Earps and Holliday marched into the corral. Somebody spoke; somebody started shooting. After a couple of minutes, Billy Clanton was dead, Frank and Tom McLowry were dead, and Ike Clanton and Billy Claiborne, having run for their lives, were safe. Morgan Earp was hit in the left shoulder; Virgil in the leg; Holliday in the left hip.

The Earp apologists have described these slayings as a triumph of law and order. In Tombstone the reaction was somewhat different. A sign over the caskets of the dead proclaimed: MURDERED IN THE STREETS OF TOMBSTONE. A mining engineer named Lewis, who had witnessed what he called cold-blooded murder, was one of three men appointed by the Citizens’ Safety Committee to tell the Earps that there should be no more killing inside the town’s limits, and that, if there were, the committee would act without regard to law; finally. Virgil Earp was fired as town marshal on October 29.

In any case, friends of those slain took matters into their own hands. Virgil Earp was ambushed and wounded on December 29. In March, 1882, Morgan Earp was picked off in the middle of a billiard game, by a sharpshooter who fired through a window from an alley in back. By this time Wyatt Earp had apparently at long last managed to be deputized by a federal marshal. (No records exist in either the Department of Justice or the National Archives to show that he ever held a regular commission as U.S. marshal or deputy.) He in turn deputized such gunmen as Doc Holliday, Turkey Creek Jack Johnson, and Texas Jack Vermillion, and took off in pursuit of his brother’s killers.

He rode and he rode, but he never came back. He rode north and east to Colorado where, he hoped, he would be safe. Behind him he left Mattie, his common-law wife, who had taken in sewing at a penny a yard when money was scarce. Behind him, too, he left a town so far from being tamed that President Chester Arthur was obliged, a few months later, to threaten martial law. It was left to a short-spoken, sawed-off, former Texas Ranger named John H. Slaughter to restore order to Cochise County.

And meanwhile, what of Bat Masterson? He had hustled back to Dodge City from Tombstone in April, 1881, in response to a hurry-up plea for help from his younger brother Jim. This worthy, still Dodge’s marshal and also co-owner of a dance hall, had got into a scrape with his partner, A. J. Peacock, and the man they employed as bartender, Al Updegraff, but Jim Masterson was apparently too timid to do his own fighting. His big brother stepped off the train at noon on April 16. Peacock and Updegraff were there waiting, and once again the tiresome shooting commenced. It was laughable. They all fired their guns empty, without effect. Some unknown hero, using a rifle, wounded Updegraff from behind. Masterson was fined $8 for shooting his pistol on the street. The Ford County “Globe” commented, “The citizens are thoroughly aroused and will not stand any more foolishness,” while the Jetmore “Republican” referred caustically to “the old gang.” Bat and his brother were ordered out of town.

Like a cat, Bat landed on his feet in Trinidad, Colorado, where in addition to running a gambling concession he appears to have been appointed a peace officer. Certainly he had some political influence. For, when an Arizona sheriff came to Denver with a request for the extradition of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, Masterson helped protect them. He got out a warrant for Holliday’s arrest on the charge of running a confidence game. This superseded the request for extradition, after which the charges against Holliday were of course dropped. “I know him well,” Bat told a reporter for the Denver “Republican,” speaking of Holliday. “He was with me in Dodge, where he was known as an enemy of the lawless element.”

But the trail led down from glory. In the iSgo’s Masterson ran a faro layout at the Arcade in Denver, then notoriously the crookedest town in the country. (Earp was dealing nearby, at the Central.) But around the turn of the century Bat was ordered to leave even Denver—it was like being told he was too low for the sewer. In 1902 he went to New York where he was at once arrested. On the train from Chicago he had, it seems, fleeced a Mormon elder of $16,000 by using marked cards in a faro game. No matter: New York was then also corrupt; Bat was bailed by John Considine, a partner of Big Tim Sullivan, who bossed the town. The elder was persuaded to mumble that he must have been mistaken when he identified Masterson. When Bat was again arrested, this time for illegally carrying a gun, his friends pulled on strings that led all the way to the White House ; and such was the magic of the Wild West legend that President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Masterson a deputy U.S. marshal for the southern district of New York. The term of the appointment was brief. Then Bat was put out to pasture as a sports writer for the “Morning Telegraph.” He died at his desk in 1921.

Meantime Earp had married a San Francisco woman named Josephine Marcus. As late as 1911 he was accused of complicity in a confidence game, but in the main he had retired to live off his investments. He died in Los Angeles in 1930. The ugliest bit of his past has been dug up, with some disgust, by Frank Waters. It concerns Mattie, the girl Earp deserted in Tombstone. Alone and friendless, Mattie drifted first to Globe and then to a mining camp near Willcox, Arizona. She was reduced to prostitution for a living. In July, 1888, she died of an overdose of laudanum, a suicide. The coroner who sent her few belongings back to her family in Iowa tucked into the package a letter in which he wrote that Mattie had been deserted by “a gambler, blackleg, and coward.” Among her effects was a Bible that had been presented to Earp when he was in Dodge. The inscription read: “To Wyatt S. Earp as a slight recognition of his many Christian virtues and steady following in the footsteps of the meek and lowly Jesus.”

Amen.

We have come at last to our fifth Horrible, a slight, short, buck-toothed, narrow-shouldered youth whose slouch adds to his unwholesome appearance. He looks like a cretin, but this may be deceptive. As we crane cautiously forward, we can see that his label reads

This young outlaw is less interesting as a human being than as a sort of Rorschach ink blot by which one may elicit fantasies and so study their inventors. It is safe to say that at least a thousand writers have used Billy the Kid as a vessel into which to pour their passions, prejudices, and opinions; but it is likely that no two portraits of him jibe. He has been endowed with every imaginable personality; from the way he has been described one could conclude that he was the original Man With a Thousand Faces; his alleged backgrounds are as various; so even are his names.

The best guess is that he was born November 23, 1859, in New York City, and called Henry McCarty. There was a younger brother, Joe. Around 1863 the family went west to Kansas. The father may have died here; at all events Mrs. Catherine McCarty was married on March i, 1873, with her two sons as witnesses, to William H. Antrim, in Santa Fé, New Mexico. The newlyweds settled in Silver City, near the Arizona border, and here Mrs. Antrim died on September 16, 1874. Henry McCarty was not yet fifteen.

He killed for the first time three years later: a blacksmith called Windy Cahill, in a saloon near Camp Grant, Arizona. There followed some gambling and some horse stealing. He was next a principal figure in the celebrated Lincoln County War, an affair which, including skirmishes and at least one pitched battle, went on for more than a year. The villains of this “war” were politicians, involved in their customary muttonheaded struggle for power, and guilty of their customary nonfeasance, misfeasance, and malfeasance. The Kid seems to have been caught up in it chiefly because he wasn’t old enough to know any better. Several persons were killed in the course of this “war,” and the Kid may have killed one or more of them; none can say for sure. In any case, his side lost, and for the rest of his brief life he was an outlaw, a hunted man.

He stole some more livestock. He killed a man named Joe Grant, who had thought to shoot first. He rode with some exceedingly case-hardened characters, including Hendry Brown, John Middleton, and Dave Rudabaugh. Sheriff Pat Garrett and a posse first caught the Kid near Stinking Springs. He stood trial for murder, was found guilty, and was sentenced to be hanged. There were two men guarding him in the jail at Lincoln, but the Kid managed James Miller, to whom Thompson gave bond for his appearance when he might be wanted later.

Is it possible Earp was not there at all?

In May, 1874, Earp arrived in Wichita, another rowdy cowtown, where, he said later, Mayor Jim Hope promptly made him the marshal. Let Earp speak: “In two years at Wichita my deputies and I arrested more than eight hundred men. In all that time I had to shoot but one man—and that only to disarm him. All he got was a flesh wound.”

And now a look at the minutes of the Wichita city commission. They show that Earp was elected on April 21, 1875, as one of two policemen to serve under the marshal and assistant marshal. They show further that on April 19, 1876, the commission voted against rehiring him. A month later it was recommended that the vagrancy act be enforced against Earp and his brother Jim.

Judging from the Wichita newspapers, Earp seems not to have won much of a reputation during his one year as a policeman. They keep referring to him as “Policeman Erp,” which makes him sound like a walking advertisement for Dr. Brown’s Celery Tonic. Now and then he arrested a suspected horse thief; but the longest newspaper story about him describes how he was arrested, fined, and fired from the police force for violating the peace on April 5, 1876. All this resulted from an election-eve fracas in which Earp slugged an opposition candidate for city marshal. And so he turned up in Dodge City, another cowtown.

•

Dodge was run by a small clique of saloonkeepers who, as the years went on, took turns at being mayor. Most saloons were routinely outfitted with gambling layouts. In 1878 the town council enacted an ordinance against gambling. Had its members gone out of their minds? No: they were moved by sound common sense. For, with a law on the books prohibiting gambling, any chump who complained that he had been cheated could be forthwith walked Spanish to the hoosegow on the grounds that he had been breaking the law.

A town run along these lines clearly required something special in the way of a peace officer: a man who would know how and when to enforce the freakish laws, who would know how to wink at the artful ways in which cowpokes from Texas were mulcted. We are told that the saloonkeeper who was mayor in 1876 sent for Wyatt Earp.

Earp told his skillful biographer, Stuart Lake, that he appointed Bat Masterson as one of his deputies. Earp also asserted that he was paid $250 a month, plus a fee of $2.50 for each arrest; he and his deputies, he said, arrested some three hundred persons a month, or enough to bring in about $750 a month. (One month in 1877, he recalled, the fees reached almost $1,000 from nearly four hundred arrests; that was the peak.) Earp’s share would have brought his income to more than $400 a month, nice money for the time and place.

And now to the town records. Earp was never marshal of Dodge. He served two terms as assistant marshal: from May, 1876, to September, 1876, and from May, 1878, to September, 1879. (During that month of 1877 when, by his own account, he and his deputies arrested nearly four hundred rowdy cowboys, Earp was not a peace officer at all. In fact, he was himself arrested that month for brawling with a dance-hall girl.) His salary as assistant marshal was $75 a month. The fee paid for an arrest (and conviction) was only $2. The docket of the police court shows that during 1878 there were only sixtyfour arrests; during 1879 there were only twentynine arrests.

One interpretation of this remarkable decline in arrests—from three hundred or four hundred a month in 1876-77 to just four a month in 1878-79 —is that lion-hearted Wyatt Earp had tamed the town. There is another interpretation.

At all events, it is clear that Earp’s income in 1878 could not have been much more than $80 a month—not much money for the time and place. Bat Masterson’s income was about the same. Both had to add to it. Both did: as professional gamblers.

It has been argued that professional gambling in the Wild West was honest. This is to impose on credulity. Obviously it was no more honest than professional gambling whenever and wherever—which is to say, no more honest than it had to be.

Earp was a professional gambler long before he got to Dodge; his reputation around Hays City, according to Dr. Floyd Streeter, a Kansas historian, was that of a card player who was “up to some dishonest trick every time he played.”

Masterson, who left Dodge in July, 1876, to follow the gold rush to Deadwood, got no further than Cheyenne, Wyoming, where he did so well as a faro banker that he stuck. But he was back in Dodge for the cattle season of 1877. On June 6 he was arrested, jugged, and fined $25 and costs for an act of hooliganism. Then he returned to his faro bank.

However, he badly wanted a star. Every professional gambler needed a star; the badge of office permitted its wearer to carry a gun, which in turn provided just the psychological advantage necessary in a game of chance played for high stakes. (Only peace officers were permitted to carry guns in Dodge City; all others were obliged to check their weapons in racks provided for the purpose.) And so Bat decided to run for sheriff of Ford County.

His electioneering technique was simplicity itself: he bought an interest in the Lone Star Dance Hall. Only thus could a candidate convince the bizarre electorate of Dodge City that he was a sound citizen and a responsible taxpayer. In November, 1877, Bat was elected by a three-vote margin. He took office in January, and what is more, he started off in high gear by catching some would-be train robbers. But as the months wore on, like Earp, and like Hickok before them both, he whiled away his evening hours as a professional gambler along with cronies like Doc Holliday, an alcoholic ex-dentist, and Luke Short, a dandiprat. Earp banked faro at the Long Branch Saloon for a percentage of the house’s gross. He and Bat and the others spent so many nights in Dodge’s brothels that they were nicknamed “the Fighting Pimps.”

There was justification for the slur. Earp lived with a girl called Mattie Blaylock; since no record of any marriage has ever been found, she is presumed to have been his common-law wife. And NyIe Miller, director of the Kansas State Historical Society, and an authority on the dossiers of Earp and Masterson, has established that, according to the census of 1880, Bat Masterson was living with Annie Ladue, nineteen, described as his “concubine,” whilst his younger brother, Jim Masterson, by then Dodge’s marshal in his turn, was living with Minnie Roberts, sixteen, also a concubine. As Mr. Miller has commented acidly, “Maybe that was the way some of the officers in those days kept watch over juvenile delinquents. They just lived with them.”

By that time Bat was no longer sheriff, having been walloped in his bid for re-election by George Hinkle, a bartender. Earp had also turned in his star. Dodge was not appreciably tamer, but the silver strike in the Arizona hills meant that there might be more money lying around loose in Tombstone ; he followed his brother Virgil there in December, 1879. With him came Mattie; with him too were other Earps, his brothers Jim and Morgan and their wives; and presently, tagging along after him, came Doc Holliday with his common-law wife, Big Nose Kate Fisher, a Dodge prostitute.

Tombstone, they soon found, was strangely unlike Dodge City. Four churches were going up. (Groton’s future headmaster, Endicott Peabody, was the young Episcopalian clergyman.) There were carpets in the saloons, forsooth, and French phrases on the menus in restaurants. No doubt about it, the Wild West was running out of steam.

Dogged traditionalists, Wyatt Earp got a job as a shotgun messenger for Wells Fargo and his brother Jim caught on as a faro banker.

Wyatt was not, as the legend has it, a United States marshal at this time. His brother Virgil was appointed a deputy marshal for southern Arizona in November, 1879, and was appointed an assistant town marshal of Tombstone in October, 1880; but Wyatt, after a brief term as civil deputy sheriff of Pima County, went back to gambling at the Oriental Saloon.

A word about Doc Holliday. He was, from every account but Wyatt’s, a mean and vicious man. He was Georgia-born, tubercular, and fond of killing. After killing two Negroes in Georgia, he fled ; after killing a man in Dallas, he fled ; after killing a soldier near Fort Richardson, he fled; after wounding a man in Denver, he fled. It was the pattern of his life. Then he met Earp. “Doc idolized him,” Masterson said later. And Earp, for his part, found much to admire in Holliday.

“With all of Doc’s shortcomings and his undeniably poor disposition,” Earp told Stuart Lake, “I found him a loyal friend and good company. …” to get hold of a gun, killed them both, and fled again, again a free man.

Garrett, implacable, continued his pursuit. One brightly moonlit night he shot and killed the Kid in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. It was July 14, 1881. Henry McCarty, alias William Bonney, alias The Kid, was not yet twenty-two.

And now the fun began.

The first book to follow the Kid’s death appeared a month later and was subtitled, “The history of an outlaw who killed a man for every year in his life,” a fiction which was seized upon and inflated by nine out of every ten writers who followed. The author of this book was a man named Fable, appropriately enough, and he described the Kid as wearing “a blue dragoon jacket of the finest broadcloth, heavily loaded down with gold embroidery, buckskin pants, dyed a jet black, with small tinkling bells sewed down the sides … drawers of fine scarlet broadcloth … and a hat covered with gold and jewels. …”

The “Police Gazette” published a biography too, as did Pat Garrett. Both poured gore liberally over the Kid. Garrett added a nice touch : he said that Billy, to show his skill, once shot the heads off several snowbirds, one after another. (J. Frank Dobie has remarked tartly, of this story, that it didn’t happen because it couldn’t happen.)

By 1889 a Frenchman, the Baron de Mandat Grancey, had written a wondrous book called “La Brèche aux Buffles"—this was his way of saying Buffalo Gap—in which he reported how Billy the Kid killed his prison guard, a man named William Bonny. Other accounts appeared : the Kid had been a dishwasher in his youth ; no, he had been a boot-black in New York City’s Fourth Ward; no, he had gone to college in the East and was really an Ivy League type.

The number of his killings mounted steadily. Soon he had killed twenty-three men, one for each of his now twenty-three years, not counting seven Mexicans whom he shot “just to see them kick.” A play about him opened in 1906 and ran for years. By 1918 its producers claimed it had been seen by ten million people. It was in 1906, too, that a dime novel appeared in which the Kid was described as an Apache who had been killed by Buffalo Bill, assisted by Wild Bill Hickok.

Then, oddly, the Kid dropped out of sight for a generation. When he reappeared, he had been twenty-four years old, and killed twenty-four men. Walter Noble Burns sentimentalized him so successfully that Hollywood brought out the first of some twenty movies about him. (Of these, the two best-known, perhaps, are those that starred Robert Taylor and Jane Russell.) Somebody made up the wonderful story that the gun Garrett had used to kill the Kid was the same gun worn by Wild Bill Hickok when he was shot in Deadwood. Somebody else wrote that the judge who sentenced the Kid ordered him to be hanged by the neck until “you are dead, dead, dead,” to which Billy retorted, “You go to hell, hell, hell!”

The further away the mythmakers got from him, the more precisely they described him. He was “a boy of talent and exceptional intelligence,” “goodnatured and of a happy, carefree disposition,” with “an unusually attractive personality.” He was also “an adenoidal moron, both constitutionally and emotionally inadequate to a high degree.” He killed forty-five men. He never killed anybody.

He was driven to a life of crime because, at the age of twelve, he killed a man who made a slurring remark to his mother. “His blue-gray eyes at times could turn cold and deadly.” Pat Garrett never shot him at all, that night at Fort Sumner, for he was still alive in 1920, when he was known as Walk-Along Smith.

In one sense, it is, of course, perfectly true that Billy the Kid did not die. He is the most imperishable of our folk heroes. Under his name there will always appear, whenever appropriate, a figure freshly refurbished so as to embody the hero who appropriately symbolizes the need of the hour : brutal killer, avenging angel, mama’s boy, slayer of capitalist dragons, bewildered cat’s paw, or gay, gallant, carefree cowpoke. The face is blank, but it comes complete with a handy do-it-yourself kit so that the features may be easily filled in.

What, in summary, of the world of the Wild West? Manifestly, it was an underworld, corrupt and rotten. Its heroes, vaunted for their courage, in fact showed only the rashness of the alcoholic or the desperation of the cornered rat. They were popularly supposed to have honored the Wild West’s socalled code, which forbade the shooting of an unarmed man and likewise the shooting of an armed man until he had been faced and warned of the peril in which he stood. But look at our five—the most celebrated heroes of all:

Hickok made his reputation by killing, from his hiding place, two unarmed men and then mortally wounding a third unarmed man who was running for his life.

Jesse James murdered at least two unarmed bank tellers, not because they had offered resistance, but when they were cowering at the bandit’s feet.

Wyatt Earp and his brothers, shielded by police badges, provoked a fight, shot first, and killed men who, according to three eyewitnesses, were holding up their hands.

Bat Masterson is saved from any similar charge chiefly because he was such a poor shot.

Billy the Kid shot and killed from ambush, not once, but several times. Indeed, only the first of his authenticated killings seems to have come about in a man-to-man fight, and even on that occasion his opponent was unarmed.

What heroes, to be exalted by the Republic!

As outlaws, they were first adored because, it was argued, they robbed only the railroad monopolist and the banker, the men most heartily hated west of the Mississippi. As law officers, they were first adored because, it was argued, they enforced the peace in perilous circumstances, against overwhelming odds. Both propositions are cockeyed. Outlaw or law officer, it made little difference, they were one brutal brotherhood. The so-called law officers more often caused than quelled crime. Hendry Brown, an outlaw in New Mexico, could ride to Kansas and pin on a sheriff’s star; Jim Younger, an outlaw in Missouri, could ride to Texas and pin on a deputy sheriff’s star; even Billy the Kid rode for a time as a member of a bailiff’s posse and, had his side won the Lincoln County War, might well have come down to us in folklore as a force for law and order. The whole boodle of them careened through lives of unredeemed violence and vulgarity, to fetch up—where else? In the Valhalla of the comics, the movies, and television.

But surely the producers of the popular entertainments do not pretend that they are purveying history? Surely they concede that their Wild West peep shows, especially on television, are at most so much embroidery basted onto the national folklore? Yet these entrepreneurs persist in using names of real people and real places. They cite dates of real occurrences—usually, to be sure, absurdly wrong. They lard their diversions with such sly phrases as “based on actual events” or “a colorful look at our American heritage.” Speaking of Wyatt Earp, they describe him as “one of the real-life heroes of yesterday … one of the greatest marshals in the annals of history … this famous straight-shootin’, fastridin’, fair-playin’, clean-livin’ lawman. …” They transform vicious, alcoholic gun fighters like Johnny Ringo and Clay Allison into sheriffs, symbols of justice and peace. They portray Jesse James as an innocent youth unfairly forced into a career of crime, and Belle Starr as a winsome, dewy-eyed ingénue who looks for all the world like Miss Cream Puff of 1960.

And even granting the assumption that the purveyors of this sludge are concerned not with history but with legend, what a shameful and ghastly legend it is ! to be despised, if not on the sufficient grounds of its ugly violence, then on the grounds of its even uglier vulgarity.

The moral, of course, is that crime, when commercially exploited, does pay, and the more sadistic the better. The Wild West—portrayed by irresponsible men who care not a hang for the truth of history so long as they can count their audiences in the scores of millions—has become a permanent industry and has created for the world an enduring image of America.

Over it there hangs the stink of evil.